Off-Label Use of Antipsychotic Medications in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Antipsychotic medications have long been a cornerstone of effective treatment for schizophrenia. Most second-generation antipsychotics have also been approved to treat bipolar disorder, and in late 2007 aripiprazole was approved for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. However, once a drug has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), clinicians are free to prescribe it as they see fit. The benefits of such off-label use are usually unclear because there has not been a high level of published clinical research evaluating the safety and efficacy of these drugs for non-FDA-approved indications. Although some off-label use of second-generation antipsychotics may be appropriate, these drugs are expensive and have serious side effects (including weight gain, diabetes mellitus, tardive dyskinesia, and extrapyramidal symptoms), and their off-label use may therefore represent significant risk and cost with undemonstrated clinical benefit and potential harm.

Several studies have investigated the extent to which antipsychotic medications have been used off label. A previous Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study found that 33.5% of patients who received a prescription for an antipsychotic medication in the VA health care system during a four-month period in 1999 did not have a diagnosis of either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder ( 1 ). A more recent study by Domino and Swartz ( 2 ), using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), found rates of off-label use of 18%–19% in 1996–1997 and 2004–2005. A report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that the most common off-label uses of second-generation antipsychotics reported in the literature were treatment of agitation in dementia and treatment of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), personality disorders, Tourette's syndrome, and autism; however, there was very little strong evidence in the literature that these drugs were effective in treating these disorders ( 3 ).

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of off-label use of antipsychotic medications for mental illness in the VA health care system in fiscal year (FY) 2007 and to explore patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with off-label use of these drugs. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing more recent estimates than the previous VA study ( 1 ). Also, because MEPS relies on patient self-report for diagnostic information ( 2 ), this study offers more precise estimates because it is based on actual prescription records.

Methods

Sources of data

Data for the study were obtained from national administrative VA databases for FY 2007 (October 1, 2006, through September 30, 2007). Data on prescriptions for antipsychotic medications came from the Decision Support System pharmacy file. This file contains data on all prescriptions filled at VA pharmacies nationwide and includes the medication prescribed, strength, number of pills per prescription, and number of days supplied. Sociodemographic and clinical data came from the Outpatient Encounter file, which contains data on all VA outpatient clinic visits nationwide. Available sociodemographic data included age, gender, and race and ethnicity. Clinical data included diagnoses (based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition [ ICD-9 ] codes) and the degree to which the patient was service connected, which is a measure of disability. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the West Haven VA Medical Center and the Yale School of Medicine.

Measures

First, all prescriptions for antipsychotic medications were identified among seven antipsychotic medication types: aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone, plus first-generation antipsychotics considered as a class. Next, outpatient records were examined to determine whether patients had any visits that indicated a diagnosis of either schizophrenia ( ICD-9 codes beginning with 295) or bipolar disorder ( ICD-9 codes 296.0, 296.1, and 296.4–296.8).

Patients without a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during FY 2007 who received an antipsychotic medication were considered to have received these medications off label. Among these patients, the average daily dose was computed for all prescriptions within seven days of the last prescription of the year by multiplying the number of pills by the strength per pill and dividing by the number of days supplied.

Doses of first-generation antipsychotics were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents.

Average daily doses were compared with the recommended dosing range for schizophrenia specified by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) ( 4 ), and patients with doses below this range were identified with a dichotomous variable. Patients without a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were assigned to the following diagnostic groups on the basis of whether they had any visits that indicated the corresponding nonexclusive ICD-9 codes: adjustment reaction (309 codes, excluding 309.81), alcohol abuse and dependence (codes 303 and 305.00), anxiety disorder (300 codes, excluding code 300.4), drug abuse and dependence (codes 292, 304, and 305.2–305.9), major depression (296.2 and 296.3), minor depression (296.9, 300.4, 301.1, and 311), organic brain syndrome and Alzheimer's disease (290, 293, 294, 310, and 331.00), other psychosis (297–299), and PTSD (309.81). Patients could belong to more than one diagnostic group.

Analysis

First, all patients who were given prescriptions for an antipsychotic medication during FY 2007 were identified, and the number and proportion of off-label users who received each drug were determined.

Next, all patients belonging to any of the nine diagnostic groups listed above (excluding those with any comorbid diagnoses of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) were identified. The proportion of patients in each of these diagnostic groups who received a prescription for an antipsychotic medication was determined, along with the average daily dose of each antipsychotic among users of that medication and the percentage with doses below the PORT-recommended dosage range for schizophrenia.

Finally, in order to identify patient-level factors associated with off-label use of these agents, logistic regression models were developed in which use of off-label antipsychotic agents was the dependent variable and the following were the independent variables: age, female gender, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, other race-ethnicity or race-ethnicity data missing, service-connected disability rating of at least 50%, service-connected disability rating of less than 50%, and diagnostic group. The service-connected disability rating is a measure of disability related to the veteran's military service. Because these models intended to predict off-label use, the sample was again restricted to individuals with no diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Separate models were run with receipt of the following antipsychotic drugs as the dependent variable: aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and first-generation antipsychotics. Because so few patients received clozapine off label, a separate model was not estimated for clozapine. A final model was estimated for receipt of any antipsychotic medication off label.

Results

Off-label use

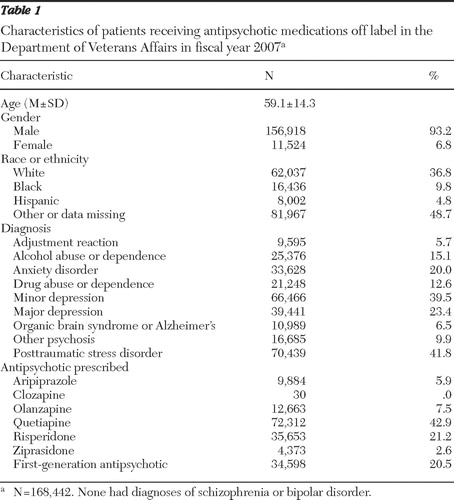

We identified 279,778 unique patients who received a prescription for an antipsychotic medication in the VA during FY 2007. Of these patients, 168,442 (60.2%) did not have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during the year and were considered to have received these drugs off label. Characteristics of off-label users of antipsychotic medications are presented in Table 1 . The average age was 59, and a large majority was male, which is reflective of the veteran population. White non-Hispanics were the most common racial-ethnic group, although almost half of off-label users fell into the "other or missing" racial-ethnic category.

|

The diagnostic breakdown of off-label users is also presented in Table 1 . Over 40% of patients given prescriptions for antipsychotic medications off label were diagnosed as having PTSD. Other relatively common diagnoses among off-label users included minor depression (39.5%), major depression (23.4%), anxiety disorder (20.0%), alcohol abuse or dependence (15.1%), and drug abuse or dependence (12.6%). There was a considerable degree of comorbidity among these disorders, given that the proportions of patients in these diagnostic groups sum to over 100%.

Quetiapine was the antipsychotic medication with the largest proportion of off-label use (42.9%). Risperidone and first-generation antipsychotics were the next most commonly prescribed off-label drugs (21.2% and 20.5%, respectively). Relatively few patients were given prescriptions for olanzapine (7.5%) or aripiprazole (5.9%) off label, and only 30 patients (<.1%) were given prescriptions for clozapine off label.

Off-label use among diagnostic groups

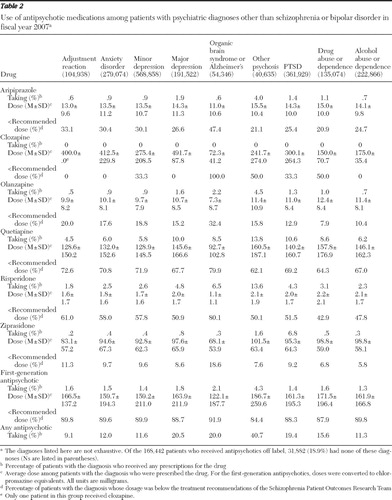

Table 2 shows the use of antipsychotic medications among patients with specific mental illness diagnoses, exclusive of comorbid schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Rates of antipsychotic use were highest among patients diagnosed as having other psychosis (40.7%), followed by major depression (20.5%), organic brain syndrome or Alzheimer's disease (20.0%), and PTSD (19.4%). Relatively few patients diagnosed as having an adjustment reaction received an antipsychotic medication (9.1%).

|

Quetiapine was the drug most commonly prescribed off label across all diagnostic groups, ranging from being prescribed to 4.5% of patients with adjustment reaction to 13.8% of the patients with other psychosis. Other than clozapine (which very few patients received off label; <.1%), ziprasidone was the antipsychotic drug next least commonly prescribed off label in most of the diagnostic groups, with rates of use ranging from .2% of patients with adjustment reaction to 1.6% of patients with other psychosis. However, ziprasidone use was relatively common among patients with PTSD (6.8%), ranking behind just quetiapine (10.6%) as the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic among these patients.

Dosing data are also shown in Table 2 . Average doses were highest for patients with other psychosis or alcohol abuse and were lowest for patients with organic brain disorder or Alzheimer's disease, although there was not much variation across diagnostic groups. However, there was considerable variation across drugs in the percentage of patients with doses below the PORT-recommended range for schizophrenia, which ranged from an average of 5.8% of patients with alcohol abuse who received ziprasidone at a dose below the PORT recommendation, to 91.9% of patients with organic brain syndrome or Alzheimer's disease who received first-generation antipsychotics below the recommended doses. Doses of quetiapine and risperidone were relatively low, with 62.1%–79.9% patients given quetiapine and 42.9%–80.1% given risperidone at doses below the PORT recommendations. The percentage of patients given prescriptions for olanzapine off label with doses below the PORT recommendations was relatively low, ranging from 7.9% to 32.4%.

Predictors of off-label use

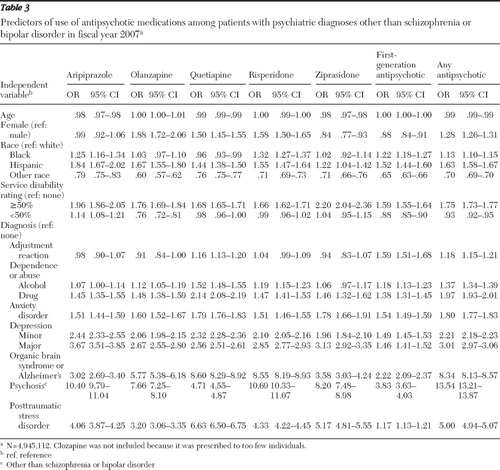

The results of the regression model predicting off-label use of any antipsychotic medication are presented in Table 3 . Although all of the independent variables were statistically significant, odds ratios (ORs) were highest for patients with a diagnosis of other psychosis (OR=13.54), organic brain syndrome or Alzheimer's disease (OR=8.34), and PTSD (OR=5.00). Being female (OR=1.28), black (OR=1.13), or Hispanic (OR=1.63) also increased the odds of receiving an antipsychotic medication off label. Patients with service-connected disability ratings of at least 50% were more likely to receive an antipsychotic medication off label (OR=1.75), and those with a disability rating of less than 50% were less likely to receive these drugs off label (OR=.93).

|

The logistic regression results were fairly consistent across the other models predicting off-label use of each medication, although there were some notable differences. In the model predicting off-label use of quetiapine, having a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome or Alzheimer's disease was associated with the largest OR (OR=8.60) of all the independent variables, followed by PTSD (OR=6.63) and other psychosis (OR=4.71). In addition, in the model predicting off-label use of first-generation antipsychotics, the likelihood of having a diagnosis of adjustment reaction was relatively high (OR=1.59), whereas this variable was not statistically significant in most of the other drug-specific models.

Discussion

In this study, we used national VA administrative data for FY 2007 to determine the extent to which antipsychotic medications are used off label and to identify factors associated with off-label use. We found a considerable degree of off-label use of these drugs; 60.2% of patients who were prescribed antipsychotic medications had no diagnosis of either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during the fiscal year. The most frequently prescribed drugs for off-label use were quetiapine, risperidone, and first-generation antipsychotics. Patients diagnosed as having another psychosis, PTSD, or organic brain syndrome or Alzheimer's disease had the highest odds of being prescribed an antipsychotic off label.

Although the rate of off-label use of antipsychotic medications was comparable with the 63.6% rate seen in the Georgia Medicaid population in 2000–2001 ( 5 ), we found a higher rate of off-label use than was found in many previous studies. A previous VA study reported that 42.8% of VA patients who were prescribed second-generation antipsychotics during a four-month period in 1999 received these drugs for an off-label use ( 1 ). At the time, second-generation antipsychotics had not been FDA approved for treating bipolar disorder, however. If patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in that study are removed, the rate of off-label use falls to 33.4%. The VA study did not include first-generation antipsychotics, which explains at least some of the difference in rates of off-label use. However, first-generation antipsychotics accounted for only 20.5% of off-label use in our study, so the exclusion of these drugs is not likely to explain all of the difference.

A more recent study based on national MEPS survey data reported that the percentages of antipsychotic medication users with an affective disorder or anxiety spectrum disorder without comorbid schizophrenia in 2004–2005 were 22% and 19%, respectively ( 2 ). Although these results are similar to those of our study (in which 20.0% of off-label users had an anxiety disorder), the MEPS study did not report rates of off-label use more generally or for other mental conditions. In addition, because MEPS contains only self-reported diagnoses, it is likely that disease prevalence was underestimated, especially for mental illnesses, which can lead to bias in the estimate of off-label use. An advantage of our study is that diagnoses were based on administrative records from actual VA clinic visits and hence may be more accurate than patient self-reports.

The rate of off-label use of antipsychotics is high compared with off-label use of other medications. Using data from a survey of office-based physicians, Radley and colleagues ( 6 ) found that 21% of all prescriptions were for an off-label use, and less than one-third of these (27%) were supported by strong scientific evidence of clinical efficacy. Rates of off-label use were highest for cardiac medications (46%), anticonvulsants (46%), and antiasthmatics (42%). Antipsychotic medications were not well represented in the study (only two were included), but this is not surprising given that the population surveyed was not limited to mental health providers.

A high rate of off-label antipsychotic use would not necessarily be of concern if there were scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of these medications for conditions other than schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. However, such evidence is generally lacking or weak. Although a meta-analysis by Schneider and colleagues ( 7 ) found a small but statistically significant benefit of aripiprazole and risperidone for treating agitation in dementia, the Alzheimer's disease arm of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (known as the CATIE study) found that second-generation antipsychotics were no more effective than placebo in treating Alzheimer's disease ( 8 , 9 ). In addition, according to a recent AHRQ report ( 3 ), the scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of off-label antipsychotic medication use is weak for most conditions, including depression and PTSD—conditions with relatively high rates of off-label use in our study.

There may be several reasons why prescription drugs are used off label. For example, the characteristics of patients enrolled in clinical trials may bear little resemblance to those of patients typically seen in clinical practice, leading clinicians to question the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, efficacy data may not exist for some conditions or populations (such as children), although pharmaceutical manufacturers have a powerful incentive to conduct clinical trials to show efficacy in conditions other than those for which their drug has been approved for use. In fact, given that aripiprazole is now approved for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder, this previous off-label use of this drug appears justified. Another possible explanation for off-label use is that clinicians try these medications as a last resort with patients who have not responded to other treatments. However, journalistic accounts suggest that some pharmaceuticals manufacturers have illegally marketed antipsychotic medications for off-label use ( 10 , 11 , 12 ).

The average dose prescribed when antipsychotic medications were used off label varied considerably across drugs. For patients with prescriptions for quetiapine, risperidone, or first-generation antipsychotics, the average dose was generally below the PORT-recommended range for schizophrenia, and a relatively large percentage of patients were given doses below the PORT recommendations. The average aripiprazole dose across all diagnostic groups was 13.8 mg per day, which is at the lower end of the PORT-recommended range of 10–30 mg per day. However, the average doses of olanzapine and ziprasidone were well within the PORT-recommended ranges for these medications, ranging from 7.3–11.4 mg per day and 68.1–101.5 mg per day, respectively, depending on the diagnosis. Further research is needed to understand why off-label dosing of some antipsychotic medications is higher than that of others.

There are a number of limitations associated with these administrative data. First, although detailed information is available on the medication and dose prescribed and number of days the medication was supplied, we could not determine what condition a medication was intended to treat because many patients received multiple psychiatric diagnoses. Hence, although we could determine whether a patient given a prescription for an antipsychotic medication had a diagnosis of PTSD, we could not say that the diagnosis of PTSD was the reason for the antipsychotic prescription because comorbid conditions were often present. Second, diagnoses were based on ICD-9 codes, which may have been miscoded or incomplete.

These data represent prescriptions written in FY 2007. At the time, no antipsychotic had been approved by the FDA for treatment of any mental disorder other than schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Aripiprazole was approved for adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder in late 2007, and more up-to-date data will be needed to evaluate the decision of this new approved usage.

Finally, our data were limited to prescriptions filled within the VA system. To the extent that patients received outpatient care or prescription medications outside of the VA, our estimates of off-label use may be biased conservatively. In addition, the VA database does not include children, a particularly vulnerable patient population that has experienced significant growth in antipsychotic use ( 2 ).

Conclusions

Antipsychotic medications are expensive ( 13 , 14 ), with second-generation antipsychotics costing about $10 per day at doses recommended for patients with schizophrenia. Total U.S. sales of second-generation antipsychotics grew from $8.4 billion in 2003 to $13.1 billion in 2007, making it the third-highest-selling medication class, behind lipid regulators and proton pump inhibitors ( 15 ). If 60% of antipsychotic medication use is off label, as our study suggests, and with consideration of the lower doses of these drugs when used off label, we estimate that $4–$5 billion of antipsychotic expenditures in 2007 may have been for off-label uses with little or no documented clinical benefit and a substantial risk of adverse side effects, such as diabetes mellitus, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms, and tardive dyskinesia. More research is needed to determine whether off-label use of antipsychotic medications yields substantial clinical benefit and to identify the basis for clinical decision making among clinicians who prescribe these drugs for non-FDA-approved conditions. Greater caution should probably be used to avoid hazardous side effects when there is limited evidence of clinical benefit.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Rosenheck has received research support from Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, AstraZeneca, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. He has been a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Organon, and Janssen Pharmaceutica. He provided expert testimony for the plaintiffs in UFCW Local 1776 and Participating Employers Health and Welfare Fund, et al. v. Eli Lilly and Company; for the respondent in Eli Lilly Canada Inc v. Novapharm Ltd and Minister of Health ; and for the Canada Patent Medicines Prices Review Board in the matter of Janssen Ortho Inc. and "Risperdal Consta." The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M: From clinical trials to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 39:302–308, 2001Google Scholar

2. Domino ME, Swartz MS: Who are the new users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatric Services 59:507–514, 2008Google Scholar

3. Shekelle P, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al: Comparative Effectiveness of Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

5. Chen H, Reeves JH, Fincham JE, et al: Off-label use of antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications among Georgia Medicaid enrollees in 2001. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:972–982, 2006Google Scholar

6. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS: Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine 166:1021–1026, 2006Google Scholar

7. Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS: Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:191–210, 2006Google Scholar

8. Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Sindelar JL, et al: Cost-benefit analysis of second-generation antipsychotics and placebo in a randomized trial of the treatment of psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:1259–1268, 2007Google Scholar

9. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al: Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 355:1525–1538, 2006Google Scholar

10. Berenson A: Drug files show maker promoted unapproved use. New York Times, Dec 18, 2006, p A1(L)Google Scholar

11. Berenson A: Lilly executive discussed off-label uses for drug. New York Times, Mar 15, 2008, p C1(L)Google Scholar

12. Berenson A: 33 states to get $62 million in Zyprexa case settlement. New York Times, Oct 6, 2008, p B7Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Busch S, et al: Rethinking antipsychotic formulary policy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34:375–380, 2008Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Doshi JA: Second-generation antipsychotics: cost-effectiveness, policy options, and political decision making. Psychiatric Services 59:515–520, 2008Google Scholar

15. Top Therapeutic Classes by US Sales. Norwalk, Conn, IMS Health, 2008. Available at www.imshealth.com . Retrieved Aug 4, 2008 Google Scholar