Integrating Forensically and Civilly Committed Adult Inpatients in a Treatment Mall Program at a State Hospital

There has been a sustained upward trend in the demand for forensic psychiatric services in the United States. This trend has translated into a reduction in the resources available for nonforensic psychiatric services ( 1 ) and has placed a strain on many state hospitals ( 2 , 3 ). It also has promoted a change in the emphasis of psychiatric services provided at state hospitals and elsewhere because, historically, the management of forensic mental health populations has focused primarily on security and risk assessment rather than therapeutic risk management based on individualized treatment and rehabilitation ( 4 ).

Forensic programs are typically segregated from civil programs at state hospitals. In many cases, forensically and civilly committed inpatients are housed and treated in different buildings or even in separate facilities. In general, aside from administrative concerns in some states, the isolation of forensic psychiatric populations from general psychiatric populations is justified on the basis of an apprehension about the nature of the offenses committed by forensic patients, these patients' perceived potential for future violence, clinicians' and administrators' fear of liability, and decreasing societal tolerance for offending behavior (particularly when the offense is perceived as having resulted from a mental disorder) ( 5 ).

Current practice for civilly committed patients suggests that treatment and rehabilitation interventions are more efficiently and effectively delivered at inpatient facilities by means of centralized programs known as "treatment malls." Treatment malls are areas away from a hospital's residential wards where patients and staff from throughout the facility meet for a significant portion of each day to receive and provide treatment, education, skills training, and support ( 6 ). Most mall services are provided in the form of treatment and rehabilitation group interventions. All ward functions, such as charting, medication administration, medical services, and meals, are transferred to the mall during its operating hours. The hospital's physical and staff resources are pooled at the mall to reduce or eliminate the need to duplicate services in residential areas. A primary objective of the mall model is to make the hospital's full complement of treatment and rehabilitation services accessible to all patients. Effective treatment malls offer service benefits such as increased amounts of programming, diversity among program users and staff, and efficiency and integration of services ( 7 ). These treatment malls provide physical and social environments in which participants are more likely to become actively engaged in rehabilitation and recovery than they would be in unit-based programs ( 8 ).

Dorothea Dix Hospital embraced the treatment mall concept and made the decision to integrate the facility's adult forensic and adult civil patients within a single treatment mall program. The program design was influenced by a need to provide the required amount of services with existing hospital resources, by a prior study that found that rates of violence in the hospital's forensic units were lower than those in a majority of the hospital's civil units ( 9 ), and by a growing body of literature suggesting that treatment and rehabilitation are more successful in less restrictive environments ( 10 ).

The purpose of this brief report is to present and analyze sample data from the Dorothea Dix Hospital treatment mall. We compared forensic and civil participants in the mall in the areas of integrated treatment and rehabilitation group sessions as well as in overall disruptiveness and dangerousness within the program.

Methods

Treatment mall data were examined for 94 forensic program participants from maximum- and medium-security residential units and for 100 civilly committed participants from long-term residential units for males and for females. The forensic and civil populations were compared during two three-month periods: January 1 through March 31 during both 2005 and 2006.

Dorothea Dix Hospital is a 350-bed state psychiatric facility located in Raleigh, North Carolina. The hospital's forensic treatment program draws patients from all of North Carolina's 100 counties. For the most part, the hospital's forensic patient population is similar to the forensic populations of other states. However, in contrast to statutes of a number of states, North Carolina statutes do not contain a conditional release mechanism for forensic patients. The consequence is potentially longer inpatient stays.

The Dorothea Dix Hospital treatment mall has three sections and is located in a central area of the main hospital building. The hospital built its mall and integrated various hospital units into the program in five phases over 31 months. The program operates 105 treatment and rehabilitation groups per weekday. Each group period lasts 45 minutes.

Patients were referred by treatment teams to mall groups and activities. Typically, program participants had an individualized mall schedule consisting of four treatment and rehabilitation sessions per weekday. Group facilitation was provided by practitioners from various hospital clinical disciplines, such as rehabilitation services, nursing, psychology, and social work. Group placements were identified on the basis of a patient's need rather than by residential unit; therefore, forensic and civil patients were routinely integrated within individual groups. Aside from groups, forensic and civil participants also shared the same common spaces for mall events such as "town hall meetings," dining, and other large gatherings.

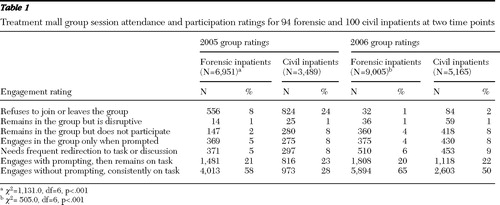

After each group session, facilitators electronically scored each participant's level of engagement in the group. The seven possible ratings were 1, refuses to join or leaves the group; 2, remains in the group but is disruptive; 3, remains in the group but does not participate; 4, engages in the group only when prompted; 5, needs frequent redirection to task or discussion; 6, engages with prompting, then remains on task; and 7, engages without prompting and is consistently on task. In addition, data were tracked regarding any use of restrictive intervention (seclusion, restraint, or physical holds) and occurrence of assaults during mall hours.

Chi square tests were used to assess differences between the forensic and civil patients in group attendance, quality of group participation, and demographic variables of race, gender, and psychiatric diagnosis. A Student's t test was used to assess any difference in age between the populations. Assaultive behavior and restrictive interventions were tracked but not analyzed because occurrence was infrequent. This study was reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Results

During both three-month periods the mall served 100 civilly committed patients. The mean±SD age of these participants was 44±11 years. Fifty-five patients (55%) were male. Fifty-three (53%) were Caucasian, 39 (39%) were African American, and eight (8%) were from other racial groups. The primary diagnoses were schizophrenia (34 patients, or 34%), schizoaffective disorder (29 patients, or 29%), other psychotic disorders (14 patients, or 14%), and other diagnoses (23 patients, or 23%).

Ninety-four forensic patients were served during the same period. The mean age was 39±13 years. Eighty-five patients (90%) were male. Twenty-nine (31%) were Caucasian, 58 (62%) were African American, and seven (7%) were from other racial groups. The primary diagnoses were schizophrenia (44 patients, or 47%), schizoaffective disorder (16 patients, or 17%), other psychotic disorders (12 patients, or 13%), and other diagnoses (22 patients, or 23%).

The demographic comparison of the two patient populations showed that the forensic and civilly committed patients differed in age (t=1.65, df=191, p=.04), race ( χ2 =16.8, df=1, p<.001), and gender ( χ2 =30.7, df=1, p<.001) but not in diagnosis ( χ2 =5.5, df=3, p=.14). The forensic population was younger, with more male and African-American patients.

The comparison of the two patient populations on measures of participation in treatment mall groups showed that the forensic patients were significantly more likely to engage without prompting and to remain consistently on task, and they were significantly less likely to refuse to join or to leave a group. This was true in both 2005 ( χ2 =1,131.0, df=6, p<.001) and 2006 ( χ2 =505.0, df=6, p<.001) ( Table 1 ).

|

Restrictive interventions data during the mall hours showed that there were relatively few episodes where any form of restrictive intervention was needed. In 2005 the forensic patients required no restrictive interventions, and there were two episodes requiring restrictions in 2006. Civilly committed patients required five restrictive interventions in 2005 and required six in 2006.

No assaults were recorded for forensic patients in 2005, and two were recorded in 2006. There was one assault by a civilly committed patient in 2005 and one in 2006.

Discussion

The quality of the forensic patients' performance in groups exceeded that of the civil patients. This is an interesting finding, given the lack of significant differences in diagnoses between the two populations. There are possible explanations for this. Forensic patients may have been admitted with less psychiatric impairment than civilly committed patients were, given that a threshold of dysfunctionality or danger to oneself or others dictates civil admissions, whereas one's legal status in the criminal justice system directs forensic admissions. Treatment and rehabilitation services delivered in integrated mall environments may "cue" many forensic patients to engage to a higher degree in rehabilitation than they would in segregated forensic wards. While at the mall, these patients are perhaps able to suspend their forensic identity and role in order to focus on personal rehabilitative objectives. A male patient from the forensic maximum-security unit of the hospital noted that when he is on his ward, he experiences only forensic rules, staff, and peers. At the mall, he decreases his defensive posture ("trying to stay out of trouble and prove to staff that I am not dangerous") to work more proactively and normally on his treatment and recovery goals. Forensic patients might be more highly motivated to participate in groups because many understand that there are numerous hurdles to overcome in order to obtain their discharge, and demonstrating cooperative participation might help their cause.

There was no evidence suggesting that the treatment mall was any less safe with the inclusion of forensic patients. Incidences of restrictive intervention and assaults were no higher for forensic patients than for civil patients and were no higher at the mall than on the wards. In fact, anecdotal information suggests that rates of such incidences were actually lower at the mall and among forensic patients.

This brief report describes an exploratory study with a limited set of sample outcomes and many uncontrolled variables. Further research is needed to measure the degree of treatment and rehabilitation effectiveness that could potentially result from forensic and civil patients' participation in integrated program settings.

Conclusions

Dorothea Dix Hospital embarked on a venture with little precedent. It successfully created and operated a treatment mall that integrated all civil and forensic patients at a hospital, which included the state's maximum-security population. This integration allowed the hospital to meet its treatment and rehabilitation programming requirements by using existing facility resources. Had the hospital been required to build a separate forensic mall—a venture the hospital could not have finally afforded—it would not have been possible for most of the forensic patients to receive the same level of services as delivered to civil patients.

Further research is needed on the potential costs and benefits of integrating forensic and civil inpatients within a single treatment mall. The hospital's experience is promising in that the integrated program proved no less safe, and the quality of treatment and rehabilitation group participation, especially on the part of forensic patients, was encouraging. A future benefit of the program is that it may help forensic clinicians perform more accurate, nonstatic risk assessments. A forensic patient's participation, performance, and improvement could be observed in integrated situations, which provide an environment that is closer than their forensic ward provides to the community into which forensic patients will eventually be discharged.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Seto MC, Harris GT, Rice ME: The criminogenic, clinical, and social problems of forensic and civil psychiatric patients. Law and Human Behavior 28:577–586, 2004Google Scholar

2. Geller JL, Fisher WH, Kaye NS: Effect of evaluations of competency to stand trial on the state hospital in an era of increased community services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:818–823, 1991Google Scholar

3. Bloom JD: Civil commitment is disappearing in Oregon. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 34:534–537, 2006Google Scholar

4. Lindqvist P, Skipworth F: Evidence-based rehabilitation in forensic psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:320–323, 2000Google Scholar

5. Mullen PE: Forensic mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:307–311, 2000Google Scholar

6. Webster SL, Harmon SH: Turning the tables: inpatients as decision makers in a treatment mall program at a state hospital. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:223–225, 2006Google Scholar

7. Webster SL, Harmon SH, Paesler BT: Building a treatment mall: a first step in moving a state hospital to a culture of rehabilitation and recovery. Behavior Therapist 28:71–77, 2005Google Scholar

8. Bopp JH, Ribble DJ, Cassidy JJ, et al: Re-engineering the state hospital to promote rehabilitation and recovery. Psychiatric Services 47:697–698, 701, 1996Google Scholar

9. Kraus JE, Sheitman BB: Characteristics of violent behavior in a large state hospital. Psychiatric Services 55:183–185, 2004Google Scholar

10. Pratt CW, Gill KJ, Barrett NM, et al: Psychiatric Rehabilitation. San Diego, Academic Press, 1999Google Scholar