How Quality Improvement Interventions for Depression Affect Stigma Concerns Over Time: A Nine-Year Follow-Up Study

Although treatment can improve health outcomes and quality of life for many people with mental illnesses, such as depression, it might also result in unintended negative consequences when patients are publicly labeled by their psychiatric treatment or illness history. In a sample of individuals with chronic mental health problems, for example, both perceived stigma and received services were related to quality of life, but in opposite directions ( 1 ). While received services had a strong positive effect on quality of life, perceptions of stigma that result from being treated had a strong negative effect on quality of life. A study of men with dual diagnoses found no change in perceptions of stigma over a year as treatment was provided ( 2 ).

Overall, little is known about how the provision of evidence-based mental health treatment or exposure to quality improvement interventions that promote the use of such treatments affects stigma concerns over time. Such information would be useful to more fully understand intervention consequences and to improve intervention design. The information could be used, for example, to help patients cope with unexpected perceived or actual long-term consequences of treatment or to promote policy changes to mitigate negative consequences. In this brief report, we present an exploratory analysis of the long-term impact of two quality improvement interventions for depression in primary care, compared with usual care, on stigma concerns nine years later, hoping to stimulate further research in this new area.

Methods

Partners in Care (PIC) is a group-level randomized trial comparing practice-level quality improvement interventions to enhanced usual care. Usual care followed written practice guidelines mailed to the medical directors. Patients who screened positive for depression on the Partners in Care screener ( 3 ) were enrolled in the study. Individuals with other diagnoses were not excluded. Two interventions were fielded: quality improvement (QI)-meds, which featured resources to support six to 12 months of antidepressant medication management, and QI-therapy, which provided resources and incentives to use cognitive-behavioral therapy ( 3 ). Both interventions offered patient and provider education, facilitated initial patient education, facilitated routing to treatments as appropriate, and provided local team intervention management.

Forty-three clinics were randomly assigned to these three groups (QI-meds, QI-therapy, and usual care). Patient and provider preferences for treatment were allowed for because the randomization was to an offer of resources that supported evidence-based care at the group or practice level, rather than assignment to treatment at the individual level. PIC found that practice-level interventions implemented in this way improved patient health outcomes and quality of care, relative to usual care, over the first two years and at five years ( 4 ).

Stigma concerns (discussed below) were measured at baseline, and baseline level of stigma concern was not significantly related to service use at six months ( 5 ). Measures of stigma concern were included again in the nine-year follow-up. Institutional review board (IRB) approval for the original study was obtained from RAND and the participating health care organizations. The nine-year follow-up was approved by the IRBs of RAND and the University of California, Los Angeles. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The quality improvement toolkits used in the intervention are available at www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/pic.html .

Of the 1,356 individuals who completed the baseline interviews, 805 also completed the nine-year interview, representing 63% of the 1,269 individuals initially enrolled and still alive at nine years. Of the 805 respondents, 196 (24%) were male, and 609 (76%) were female. A total of 499 (62%) were white, 46 (6%) were black, 206 (26%) were Hispanic, and 54 (7%) were of another race or ethnicity. A total of 254 (32%) were in the usual care group, 284 (35%) were in the QI-therapy group, and 267 (33%) were in the QI-meds group. A total of 365 (45%) had anxiety, 496 (62%) had a depressive disorder, and 309 (38%) had subthreshold depression, as measured at baseline.

At the baseline and nine-year follow-up interviews the respondents were asked the following questions: If you were applying for a job, how much difficulty do you think you would have getting the job if the employer thought you had a recent history of the following? If you were switching to a new health insurance policy, how much difficulty do you think you would have getting the policy if the insurer knew you had a recent history of the following? How much would your relationships with friends suffer if they thought you had a recent history of the following? Respondents were asked about depression and visiting a psychiatrist. The variables were dichotomized, with the response categories "none" and "a little" compared with "some" and "a lot."

We created indicators for each intervention—QI-meds and QI-therapy—versus the control group. We included sociodemographic variables (age, gender, race or ethnicity, marital status, education level, and family wealth) and clinical variables (chronic medical condition, anxiety status, depression status, and scores on the mental component summary [MCS-12] and the physical component summary [PCS-12] of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey) ( 6 ) measured at baseline as covariates in the model.

We conducted patient-level, intent-to-treat analyses based on the intervention assignment of the clinic in which the patients were receiving care at the time of study enrollment. For the stigma variables assessed in the nine-year follow-up, we estimated logistic regression models with intervention status as the independent variable, controlling for the covariates listed above. We conducted sensitivity analyses by including baseline measures of the dependent variable as an additional covariate, with no change in results. We used an F test to determine whether there was an overall difference among the three intervention arms (QI-meds, QI-therapy, and usual care) and t tests for pairwise comparisons of the two intervention arms. We adjusted for patient clustering within clinics by using a modification of the robust variance estimator, the bias-reduced linearization method ( 7 ). Multiple imputations ( 8 ) were used to account for item-level missing data. Other nine-year PIC analyses that also included five-year follow-up data have used unit imputation to adjust for unit nonresponse. Because stigma concerns were not measured at five years, we did not employ unit imputation for this analysis. Baseline stigma concerns were not significantly related to participation in the nine-year survey, after the analyses controlled for other baseline predictors in logistic regression models.

Results

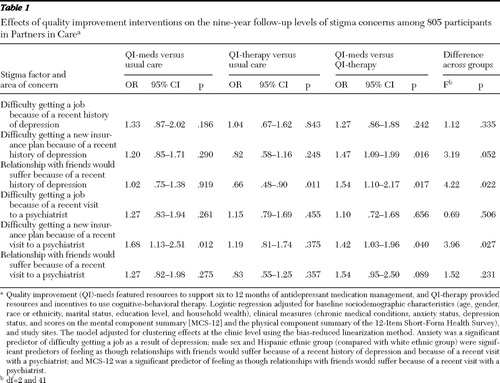

Table 1 shows that at the nine-year follow-up, after control for the covariates listed above, the QI-therapy group was significantly less likely than those in usual care to report concerns about friends learning of a recent history of depression (odds ratio [OR]=.66), whereas the QI-meds group was significantly more likely than the QI-therapy group to report these concerns (OR=1.54). The QI-meds group was significantly more likely than usual care (OR=1.68) or the QI-therapy group (OR=1.42) to report concerns about getting a new insurance plan if the insurer learned that they had visited a psychiatrist. The QI-meds group also reported more insurance concerns about a history of depression than the QI-therapy group, but the overall intervention test was not significant (p=.052).

|

In addition, we found that compared with individuals in the respective comparison groups (whites was the comparison group for Hispanics), those with a probable anxiety disorder at baseline (as measured by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview [9]) were significantly more likely to report concerns about getting a job if the employer knew that they had been depressed (OR=1.63, CI=1.08–2.45, p=.021), whereas men (OR=1.57, CI=1.04–2.37, p=.037) and Hispanics (OR=1.67, CI=1.06–2.62, p=.028) were significantly more likely to report concerns about friends learning that they had depression. In addition, men (OR=1.50, CI=1.04–2.20, p=.042) and Hispanics (OR=2.08, CI=1.28–3.36, p=.004) and individuals with poorer mental health at baseline (as measured by the MCS-12) (OR=.98, CI=.96–1.00, p=.019) were significantly more likely to report concerns about friends learning that they had visited a psychiatrist (models available from the corresponding author).

Discussion

At nine years we found a statistically significant reduction in concerns about losing friendships as a result of a history of depression among individuals in the QI-therapy group, compared with the usual care and QI-meds groups, without evidence of an increase in job or insurance concerns. The QI-therapy intervention supported cognitive-behavioral therapy, which reinforced cognitive and behavioral learning and offered education from providers and care managers. In general, cognitive treatment models focus on strategies to alter interpretations of events that occur that are unduly negative ( 10 ). The QI-therapy intervention could have lowered stigma concerns over time by promoting better outcomes that resulted in improved social relationships. Alternatively, the improvement could have been due to the use of cognitive reframing techniques that allow for improved direct problem solving about such stigma concerns. The study design did not allow us to determine which of the QI-therapy components was responsible for this effect. We also cannot determine when the effect occurred during the nine-year follow-up period, because we did not measure stigma concerns in the intermediate follow-up surveys.

To our knowledge, this is the first suggestion that a quality improvement program for depression that promotes the use of evidence-based psychotherapy can reduce stigma concerns about a mental health condition in the long run. From a consumer perspective, a reduction in stigma concerns could be viewed as an important primary outcome of such a program. In addition, such a reduction could set the stage for future help seeking at a time of need. Because specific groups, such as men, Hispanics, and those with poorer mental health, had more concerns about losing friendships, it might be helpful to target them for more in-depth education about stigma.

We found that compared with usual care, the QI-meds intervention increased concerns about obtaining a new insurance plan if the insurer learned of a psychiatric visit. Because insurers may deny new insurance plans to individuals with preexisting conditions ( 11 ) this issue merits additional study. This is especially important because the majority of individuals with treatable mental disorders do not access care and may be hesitant to do so in light of fears of discrimination by insurers. We reported elsewhere ( 12 ) that the interventions appear to have increased some barriers to mental health care at nine years, especially among whites. An increase in insurance concerns was found in the study reported here, using different measures within the nine-year survey. Thus we are particularly confident that at least some participants developed increased concerns about insurance over the course of the study, despite the intervention leading to better health and quality of care.

There are important limitations to these findings, including use of particular health care systems in particular U.S sites, moderate response rates, a lengthy follow-up period (nine years) without intermediate stigma measures, and a reliance on self-report measures. Further, clinics, rather than individuals, were randomly assigned to treatment groups in this study, raising concerns about comparability of individuals, although we controlled for relevant baseline differences in our analyses. Further, as noted, because resources for treatment rather than treatments per se were randomly assigned, we cannot determine whether treatment itself versus the broader context of the intervention led to these results.

Conclusions

This study has important implications for future research. Recent policy reports describe stigma as the most formidable obstacle to future progress in care of mental illness ( 13 , 14 ). Quality improvement programs for depression that promote the use of evidence-based psychotherapy may hold promise to reduce stigma concerns about friends learning about a depression history, whereas similar programs that promote the use of medication in the absence of policy change may increase long-term concerns about insurance coverage.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by grants MHR01070260, MH068639, and MH61570 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Rosenfield S: Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 62:660–672, 1997Google Scholar

2. Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al: On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:177–190, 1997Google Scholar

3. Wells KB: The design of Partners in Care: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of improving care for depression in primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:20–29, 1999Google Scholar

4. Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al: Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:378–386, 2004Google Scholar

5. Roeloffs C, Sherbourne C, Unützer J, et al: Stigma and depression among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 25: 311–315, 2003Google Scholar

6. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473–483, 1992Google Scholar

7. Bell RM, McCafrey DF: Bias reduction in standard errors for linear regression with multi-stage samples. Survey Methodology 28:169–179, 2002Google Scholar

8. Schafer J: Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, Chapman and Hall, 1997Google Scholar

9. Beck AT: Cognitive therapy: a 30-year retrospective. American Psychologist 46:368–375, 1991Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Google Scholar

11. Wahl OF: Mental health consumers' experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25: 467–478, 1999Google Scholar

12. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Miranda J, et al: The cumulative effects of quality improvement for depression on outcome disparities over 9 years: results from a randomized, controlled group-level trial. Medical Care 45:1052, 2007Google Scholar

13. Hogan MF: New Freedom Commission report: the President's New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatric Services 54:1467, 2003Google Scholar

14. Satcher D: Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General—executive summary. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 31:15–23, 2000Google Scholar