Identifying Clinically Questionable Psychotropic Prescribing Practices for Medicaid Recipients in New York State

With dual goals of improving health outcomes and containing unnecessary pharmacy expenditures, the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS OMH) has begun a four-year initiative (led by Molly T. Finnerty, M.D.) to improve the quality of psychotropic prescribing practices for Medicaid beneficiaries. A central objective of this initiative is to provide prescribers, clinic managers, and state administrators throughout New York State with clinical strategies to reduce questionable prescribing, along with concurrent performance data on quality indicators derived by use of current Medicaid claims data.

New York State Office of Mental Health Scientific Advisory Committee members who are coauthors of this article

Stephen J. Bartels, M.D., M.S., Departments of Psychiatry and Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Center for Aging Research, Lebanon, New Hampshire

Robert W. Buchanan, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore

Peter F. Buckley, M.D., Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta

Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D., School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio

Robert R. Conley, M.D., University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana (Dr. Conley stepped down from the committee when he accepted the position at Lilly.)

Lisa B. Dixon, M.D., M.P.H., Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Department of Veterans Affairs Capitol Health Care Network, and Division of Health Services Research, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore

Graham J. Emslie, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas

Robert L. Findling, M.D., Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, and Departments of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio

Jean A. Frazier, M.D., Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester

Donald C. Goff, M.D., Freedom Trail Clinic, Massachusetts General Hospital Schizophrenia Program, Boston

Laurence L. Greenhill, M.D., Department of Clinical Psychiatry, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York City

Dilip V. Jeste, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego

John M. Kane, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, New York

Stephen R. Marder, M.D., Semel Institute of Neuroscience at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Department of Veterans Affairs Desert Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center

Barnett S. Meyers, M.D., Department of Clinical Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York City

Alexander L. Miller, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Andrew A. Nierenberg, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston

Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York City

Steven P. Roose, M.D., College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York City

Lon S. Schneider, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Gerontology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

Nina R. Schooler, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Downstate Medical Center, State University of New York, Brooklyn, and Department of Veterans Affairs Capitol Health Care Network, Washington, D.C.

M. Katherine Shear, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, School of Social Work, Columbia University, New York City

Bradley D. Stein, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and Community Care Behavioral Health Organization, Pittsburgh

T. Scott Stroup, M.D., M.P.H., Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York City

Michael E. Thase, M.D., University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia

Karen D. Wagner, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston

Katherine L. Wisner, M.D., M.S., professor of psychiatry and obstetrics and gynecology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

To bring the most current science to bear, OMH partnered with the Division of Mental Health Services and Policy Research (DMHSPR) of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University to identify experts who contribute regularly to the scientific literature on psychopharmacology. OMH invited several of these experts to serve on a Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) to identify prescribing practices that may, under some circumstances, be considered clinically questionable (a list of all SAC members is available at https://psyckesmedicaid.omh.state.ny.us/common/advisoryc.aspx ). In identifying such practices, SAC members recognized that some practices might constitute appropriate care for a particular person, such as prescribing valproate as a first-line treatment to a woman of reproductive age who is not planning to become pregnant and is actively preventing pregnancy. Thus the committee recommended that the indicators be used to identify potential quality concerns, which would then trigger a clinical review that would determine whether the concern was justified and a change in medication regimen was warranted. Clinical reviews would be particularly warranted for prescribers with many such outliers.

In this article, we describe the SAC's recommendations for quality indicators of clinically questionable prescribing practices and provide prevalence data regarding a subset of these quality indicators.

Methods

Development of indicators

The SAC was formed in August 2007, and DMHSPR convened six workgroups— schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, women, youth, and older adults. Topics for the workgroups were chosen a priori on the basis of both the frequency of diagnoses among individuals receiving services and the populations of particular concern. The workgroups identified clinically questionable practices that can be measured by using pharmacy claims and that are relevant for the population under consideration. After an extensive vetting process both within and between workgroups, the entire SAC reviewed and approved the lists of indicators of potential quality concerns.

Data for estimating prevalence of potential concerns

The Psychiatric Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System (PSYCKES) Data Analysis Committee examined state Medicaid data and determined that in the first quarter of 2008, a total of 752,647 New York State Medicaid recipients generated claims paid by Medicaid and had a claim in the previous two years for a psychiatric diagnosis or mental health service. Historical data for up to five years were available for some persons. Of the 752,647 recipients, 298,448 (40%) filled one or more prescriptions for psychotropic medications in the three months preceding April 1, 2008. Seventy-three percent (N=217,216) of this group had at least one active psychotropic medication prescription on April 1, 2008. A medication was considered active on April 1, 2008, if that day fell between the prescription fill date and the last date covered by the number of days of medication supplied.

Of the 217,216 individuals, 56% were female (N=120,768), and the group's mean age was 40±18 years (median 43.5). On the basis of data from the Medicaid claims, 49% (N=105,809) of the sample were identified as Caucasian, 21% (N=45,727) were identified as African American, and 15% (N=32,098) were identified as Hispanic. Approximately 12% (N=26,566) of the sample had Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage on or before April 1, 2008. Because the analyses did not include Medicare claims, some groups with members who were also likely to receive Medicare benefits, such as adults age 65 and older, were underrepresented in the sample. Individuals residing in state psychiatric centers are also not included in Medicaid claims.

Operational definitions for indicators of potential concerns

Polypharmacy. Polypharmacy was defined as a period of simultaneous prescribing of psychotropic medications for longer than 90 days ( 1 ), both within and across drug class (antipsychotics, antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, nonantipsychotic mood stabilizers, and stimulants). Within this 90-day period, we allowed up to a 15-day gap in the polypharmacy regimen. Multiple forms of the same medication were counted as a single medication. Antidepressant polypharmacy excluded trazodone, and polypharmacy of two or more antidepressant medications was considered by subclass—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Medications were assigned to drug classes by U.S. Food and Drug Administration indication, except for lithium formulations, which were categorized as mood stabilizers only. Off-label medications were added according to SAC recommendations. [A list of psychotropic medications included, by drug class, is available as an online supplement to this article (Appendix 1) at ps.psychiatryonline.org ]

Gaps of up to 32 days between the last day of medication supply and the next fill date were considered part of the same medication trial to allow for less-than-perfect adherence and short inpatient stays. Depot antipsychotics were considered active for durations consistent with bioavailability of medication over time (haloperidol decanoate, 28 days; fluphenazine decanoate, 21 days; and injectable risperidone, 14 days).

Questionable use of benzodiazepines. An indicator of clinically questionable use of benzodiazepines was constructed by identifying individuals with active trials of sedative-hypnotic medications of any duration. To calculate prevalence of long-term use among youths, trials of benzodiazepines were extracted for recipients under age 18, with trial lengths of greater than 90 days identified as long-term use.

Questionable medication choice given medical considerations or age. An indicator of clinically questionable antipsychotic prescribing in the presence of cardiometabolic concerns was constructed by identifying all individuals with an active prescription for an antipsychotic medication who had one or more of the following conditions: diabetes or hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, ischemic vascular disease or acute myocardial infarction, hypertension, or obesity. An individual was considered to have a particular condition if, in the previous two to five years (depending on the data available for an individual), there were two outpatient diagnoses, one inpatient diagnosis, or a medication used to treat the condition (for example, insulin for diabetes). [A complete list of diagnoses and medications is available as an online supplement to this article (Appendix 2) at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Separately, the SAC schizophrenia subcommittee reviewed the list of antipsychotic medications categorized by the American Diabetes Association-American Psychiatric Association Guidelines ( 2 ) as having either a moderate or high risk of exacerbating cardiometabolic conditions; the subcommittee then revised the list on the basis of recent evidence ( 3 ). Although clozapine is associated with high risk for metabolic abnormalities, the SAC schizophrenia subcommittee recommended excluding clozapine from the list of medications that would trigger this indicator for adults in order to avoid further stigmatizing the use of a medication that is viewed by this SAC subcommittee as underutilized and that is already restricted to individuals for whom other antipsychotics have failed. For adults, antipsychotic medications considered to pose moderate or high risk for use by individuals with metabolic disturbances included chlorpromazine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and thioridazine. The SAC youth subcommittee recommended that the medications considered to pose moderate or high risk for metabolic abnormalities for youths aged 18 and under include those identified for adults plus risperidone, paliperidone, clozapine, and all first-generation antipsychotic medications.

To compute the prevalence of the potential quality concern captured by this cardiometabolic indicator, the numerator included individuals with evidence of one or more cardiometabolic conditions and with an active prescription for at least one moderate- or high-risk antipsychotic medication and the denominator included individuals with a cardiometabolic condition with an active prescription for any antipsychotic medication. Data for this indicator were extracted on April 23, 2008.

An indicator of clinically questionable use of valproic acid among women of reproductive age was created because valproic acid and related compounds are now discouraged as first-line agents for women in this group ( 4 , 5 ) because 10% of women have been found to develop rapid onset of polycystic ovarian syndrome ( 6 ) and because of teratogenic effects of valproate. This indicator included women of reproductive age (based on the World Health Organization's definition of women ages 15 to 49 [7]) who had a prescription for a mood stabilizer [see online Appendix 1 at ps.psychiatryonline.org ]. The numerator included those with an active trial of valproic acid (divalproex or valproate), and the denominator included all women in the identified cohort.

An indicator of clinically questionable use of psychotropic medications for children under age six was created by the youth subcommittee of the SAC in recognition of the increasing use of such medications in very young children despite the lack of an evidence base to support the practice. The prevalence of this indicator was calculated as the number of children under age six who were prescribed any psychotropic medication divided by the number of all youths under age 18 who were prescribed any psychotropic medication.

Metabolic monitoring. An indicator of apparent absence of appropriate metabolic monitoring was created to acknowledge the importance of monitoring lipids and glucose for individuals taking antipsychotics known to cause such metabolic disturbances ( 2 , 8 ). The numerator included individuals taking a moderate-to-high risk antipsychotic (as defined above) without evidence of lipid and glucose screening in the previous year, as indicated by an absence of claims for a comprehensive metabolic panel, general health panel, glucose (including glucose tolerance tests and blood reagent tests), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), or cholesterol (including high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and very-low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides. The denominator included all individuals with a prescription for any moderate-to-high-risk antipsychotic.

Results

Indicators of clinically questionable prescribing

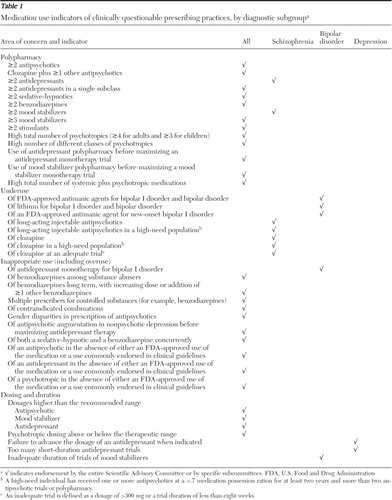

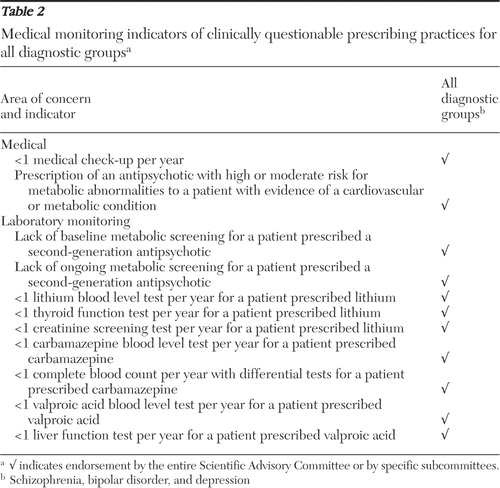

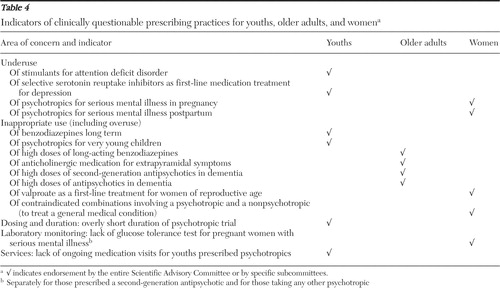

Tables 1 , 2 , and 3 provide a list of quality indicators by diagnostic subgroup for medication use, medical monitoring, and patient-centered care, respectively. Table 4 provides a list of quality indicators for youths, older adults, and women. Rather than setting specific targets for proposed indicators, the SAC underscored that appropriate rates of conformance would be expected to vary on the basis of client age, diagnosis, treatment setting, and specific quality indicator. For example, levels of polypharmacy were expected to be lower among youths and older adults and in primary care settings.

|

|

|

|

Prevalence of particular questionable practices

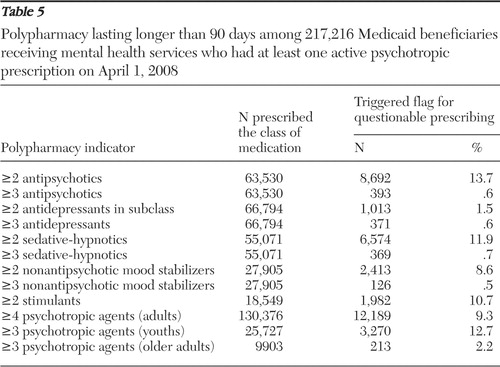

Polypharmacy. Of 217,216 Medicaid beneficiaries with an active psychotropic prescription on April 1, 2008, a total of 156,103 (72%) had one or more prescriptions for psychotropics for longer than 90 days. Of this group, 84% (N=130,376) were adults, and 10% (N=12,789) of these adults had four or more concurrent psychotropic trials lasting longer than 90 days. The remaining 16% (N=25,727) were youths (under age 18), and 13% (N=3,270) of these youths had three or more concurrent psychotropic trials. In addition, of 9,903 adults age 65 and older, 213 (2%) had three or more concurrent psychotropic trials.

Percentages of individuals prescribed clinically questionable polypharmacy decreased markedly as thresholds increased for identifying a quality concern. For example, over 13% of individuals taking at least one antipsychotic were prescribed two or more antipsychotics concurrently, whereas less than 1% of individuals taking at least one antipsychotic were prescribed three or more concurrent antipsychotics ( Table 5 ). Of the 8,692 individuals prescribed two or more antipsychotics concurrently, 55% (N=4,790) had a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis, and of the 393 individuals prescribed three or more antipsychotics concurrently, 63% (N=246) had a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis.

|

Questionable use of benzodiazepines. Prescriptions of benzodiazepines for youths in the sample were rare. Only 431 (2%) individuals under age 18 were prescribed a benzodiazepine; however, almost half of these youths (N=209, 48%) had a trial length of over 90 days.

Questionable medication choice given medical considerations or age. Prescribing an antipsychotic with moderate-to-high risk of metabolic abnormalities to individuals with evidence of a cardiometabolic condition approached 50% (46%, N=8,612 of 18,880). In addition, among the 13,698 women of reproductive age who were prescribed a mood stabilizer, over one-quarter were prescribed valproic acid (30%, N=4,059). Among the 46,828 youths under age 18 who were prescribed a psychotropic medication, 3% were under age six (N=1,212).

Metabolic monitoring. Among individuals prescribed an antipsychotic medication considered moderate-to-high risk for metabolic abnormalities (N=49,795), more than half (60%, N=29,751) did not have evidence of metabolic screening in the past year. The rate was higher for children (74%, N=9,155 of 12,372) than for adults (55%, N=20,818 of 37,745).

Discussion

The Medical Directors Council of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors recently published a policy statement to assist policy makers in responding to new evidence regarding psychotropic prescribing practices ( 9 ). They identified critical strategies for supporting evidence-based practices, including monitoring performance and developing interventions to support appropriate practices and to curtail inappropriate ones. Our report reflects one such undertaking to identify clinically questionable prescribing practices and to characterize the prevalence of a subset of these practices among Medicaid recipients receiving mental health services in New York State. Psychopharmacology experts reached a consensus as to what constituted clinically questionable prescribing practices. For indicators that were operationalized and examined via claims data, we identified substantial numbers of individuals who received prescriptions that presented potential quality concerns.

Rates of polypharmacy were consistent with rates previously reported ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ). Other than in limited situations involving clozapine ( 17 , 18 ), evidence for the effectiveness of polypharmacy is weak and inconsistent. Therefore, it is particularly difficult to set a target or criterion level for the prevalence of polypharmacy. Absent strong data to support the practice, the SAC recommended flagging and reviewing all instances of psychotropic polypharmacy to determine the frequency and patterns of this practice. This information could then be used to achieve the goals of simplifying medication regimens when clinically appropriate, thereby reducing patient risks. Depending on which medications are discontinued and how the remaining dosages are adjusted, reducing polypharmacy may also be accompanied by cost savings ( 19 ).

Rates of prescribing antipsychotics that pose a moderate-to-high risk of metabolic abnormalities to individuals with existing cardiometabolic conditions were so high as to prompt OMH to select this indicator, along with polypharmacy, as one of the first two to pursue with statewide quality improvement initiatives ( https://psyckesmedicaid.omh.state.ny.us ). Also, among those receiving an antipsychotic posing a moderate-to-high risk of metabolic abnormalities, fewer than half had evidence of concurrent screening of metabolic functioning (and rates were even lower for children prescribed these medications). This suggests that clinicians may benefit from outreach and education on the relative risks of metabolic abnormalities presented by various antipsychotics, on the importance of monitoring metabolic functioning when prescribing an antipsychotic that is known to exacerbate cardiometabolic conditions, and on strategies for managing clients who develop cardiometabolic conditions while taking a moderate-to-high-risk antipsychotic. They may also benefit from assistance in obtaining monitoring tests more easily. Initially, an increase in monitoring may increase costs because of the need to carry out laboratory tests and to provide treatment for newly identified cardiometabolic conditions. However, longer-term cost savings may follow from improvements in cardiometabolic outcomes.

Prevalence data suggest that 30% of women of reproductive age who were prescribed a mood stabilizer took valproic acid. Whether these women were known by their prescribers to be using birth control or were women for whom previous trials with less teratogenic mood stabilizers had not provided adequate relief is unknown. One also cannot say what proportion of youths prescribed long-term benzodiazepines is too high, or how long is too long, or what the rate of prescribing long-acting benzodiazepines for older adults should be and at what dosage.

For each of these questionable practices, reasonable next steps include providing feedback to prescribers and administrators as well as identifying where outliers concentrate. Analyses of outliers can be an efficient way to identify and investigate potential quality concerns absent definitive data from clinical trials as long as the data are timely enough to reflect current practice (as is now the case with pharmacy claims). Clinical practice is broader than the topics covered by experimental evidence; thus monitoring and examining outliers at the patient, provider, and agency levels offer some safeguards absent an evidence base. Monitoring at each level allows different interventions for outlier prescribers and agencies. Procedures could be reviewed in settings that are "good outliers" to identify characteristics of "positive deviants" ( www.positivedeviance.org ).

The study has several limitations. The SAC underscored the importance of adjusting performance expectations by setting, caseload mix, and other factors that are yet to be incorporated. Further work is needed to characterize high and low outliers, including how these outliers cluster by prescriber and by setting as well as by individual characteristics. Ideally, one would like to know the sensitivity and specificity of quality measures before implementing interventions. It will be important to establish that improving performance on these measures leads to better outcomes. The SAC members underscored that they would need data on rates characterizing variation across providers and across settings to establish performance targets. Older adults are underrepresented in this database, which limited estimates of questionable prescribing in that group. In addition, data are from a single large state, with one of the largest Medicaid programs in the country, serving an unusually diverse population. Finally, data are from administrative claims and subject to limitations inherent in such data. Although such data may provide a benchmark to measure quality improvement initiatives, targeted interventions must incorporate knowledge of physician characteristics, client characteristics, setting, region, and other influences. The performance metrics presented here represent one attempt, among many, to begin quantifying treatment decisions, and indiscriminate adoption of these metrics would be premature.

These limitations notwithstanding, the indicators of clinically questionable prescribing practices described here reflect pressing quality concerns informed by the most recent scientific evidence, and knowledge of the point prevalence of a subset of these indicators creates opportunities to detect changes over time. The timely availability of pharmacy claims maximizes the clinical relevance of administrative data to improve care for specific individuals even as aggregation of such data to identify prescriber and agency outliers allows for more traditional quality improvement approaches.

Conclusions

Psychopharmacology experts generally agree on the prescribing practices that constitute clinically questionable care, and recent data from New York State indicate that some questionable practices are quite common across all age groups. Pharmacy claims data can be used to identify questionable practices, such as those reported here, and aggregation and review of these data can be a core component of efforts to improve prescribing practices.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank members of the PSYCKES Data Analysis Committee Nitin Gupta, M.S., and Qingxian Chen, M.S., for their work in the analysis of data. Other members of the Scientific Advisory Committee are Patricia E. Deegan, Ph.D., Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., and Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D.

Dr. Lieberman has served as an uncompensated consultant or advisor or has received research support from Allon, AstraZeneca, Bioline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, Merck, Solvay (Data Safety Management Board [DSMB]), and Wyeth. He holds a patent from Repligen. Dr. Finnerty has received project donations from AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Buchanan has served as a consultant or advisor to Abbott, AstraZeneca, Cephalon (DSMB), GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer (also DSMB), Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Schering-Plough, Solvay, and Wyeth and has received study medications from Janssen Pharmaceutica and Ortho-McNeil. Dr. Buckley has received research support from or served as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, Solvay, and Wyeth. Dr. Calabrese has received research support from, served as an advisor to, or conducted CME activities for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson, Organon, Ortho-McNeil, Servier, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synosia, and Wyeth. Dr. Conley is an employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly. Dr. Dixon has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Emslie has served as a consultant to or has received research support from Biobehavioral Diagnostics Inc., Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Pfizer, Shire, Somerset, and Wyeth. Dr. Findling has received research support from or has served on the speakers bureau of or as a consultant to Abbott, Addrenex, AstraZeneca, Biovail, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm, Lundbeck, Neuropharm, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis, Sepracore, Shire, Solvay, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Validus, and Wyeth. Dr. Frazier has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Neuropharm, Otsuka American Pharmaceutical, and Pfizer. Dr. Goff has served as a consultant or advisor to or received research support from Eli Lilly, Indevus Pharmaceuticals, Imedex, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lundbeck, Novartis, Pfizer (DSMB), Schering-Plough, and Wyeth (DSMB). Dr. Greenhill has received research support from Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Jeste has received study medication for his NIMH-funded research grant from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Janssen Pharmaceutica. Dr. Kane has served as a consultant or advisor to or on the speakers bureau of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, PGxHealth, and Wyeth. Dr. Marder has received research support from or served as a consultant or advisor to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis, and Wyeth. Dr. Meyers has received research support from Forest Research Institute and study medications from Eli Lilly and Pfizer and has provided legal consultation to AstraZeneca. Dr. Miller has received research support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Research Foundation, Organon, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi Aventis. Dr. Nierenberg has served as a consultant or advisor to or received research support from Appliance Computing, Inc. (also stock options), Brain Cells, Inc. (also stock options), Ortho-McNeil-Janssen, Novartis, Pam Labs, Pfizer, PGX Health, Shire, Takeda, and Targacept. Dr. Olfson has received research support from or served as a consultant to or on the speakers bureau of AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer. Dr. Roose has served as a consultant to Forest Laboratories, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis, and Wyeth. Dr. Schneider has served as a consultant to or received research support or supplies from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, SmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis, Takeda, and Wyeth. Dr. Schooler has received research support or supplies from or served as an advisor to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Pfizer, and Schering-Plough. She owns stock (in trust) in Redox Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stein has received research support from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs. Dr. Stroup has served as a consultant to Janssen and Eli Lilly. Dr. Thase has served as a consultant or advisor to or on the speakers bureau of or has received research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Inc., Cyberonics, Inc., Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, MedAvante, Inc. (also equity holdings), Neuronetics, Inc., Novartis, Organon, Sanofi Aventis, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Inc., Shire, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth. He has provided expert testimony for Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth. His spouse in employed by Advogent. Dr. Wisner has received research supplies from Novagyne and serves as an advisor to Eli Lilly. The remaining authors have no interests to disclose.

1. Leckman-Westin E, Finnerty M, Gupta N, et al: Using administrative data to inform prescribing practices: antipsychotic polypharmacy indicator development. Presented at the State Mental Health Agency Services Research, Program Evaluation and Policy Conference, Arlington, Va, Feb 11–13, 2008Google Scholar

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:596–601, 2004Google Scholar

3. Meyer JM, Davis VG, McEvoy JP, et al: Impact of antipsychotic treatment on nonfasting triglycerides in the CATIE schizophrenia trial phase 1. Schizophrenia Research 103:104–109, 2008Google Scholar

4. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics: ACOG Practice Bulletin, no 87, 2007: use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. Obstetrics and Gynecology 110:1179–1198, 2007Google Scholar

5. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: The NICE Guidelines on Clinical Management and Service Guidance. Leicester, United Kingdom, British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2007Google Scholar

6. Joffe H, Cohen LS, Suppes T, et al: Valproate is associated with new-onset oligoamenorrhea with hyperandrogenism in women with bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry 59:1078–1086, 2006Google Scholar

7. Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations: An Inter-Agency Field Manual. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1999Google Scholar

8. Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, et al: Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1334–1349, 2004Google Scholar

9. Parks J, Radke A, Parker G, et al: Principles of antipsychotic prescribing for policy makers, circa 2008: translating knowledge to promote individualized treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 35:931–936, 2009Google Scholar

10. Botts S, Hines H, Littrell R: Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the ambulatory care setting, 1993–2000. Psychiatric Services 54:1086, 2003Google Scholar

11. Faries D, Ascher-Svanum, Zhu B, et al: Antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy in the naturalistic treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics. BMC Psychiatry 5:26, 2005Google Scholar

12. Ganguli R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, et al: Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy among Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998–2000. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:1377–1388, 2004Google Scholar

13. Kreyenbuhl JA, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, et al: Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 84:90–99, 2006Google Scholar

14. Kreyenbuhl JA, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, et al: Long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy in the VA health system: patient characteristics and treatment patterns. Psychiatric Services 58:489–495, 2007Google Scholar

15. Tapp A, Wood AE, Secrest L, et al: Combination antipsychotic therapy in clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 54:55–59, 2003Google Scholar

16. Tempier RP, Pawliuk NH: Conventional, atypical, and combination antipsychotic prescriptions: a 2-year comparison. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:673–679, 2003Google Scholar

17. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al: Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia Bulletin 35: 443–457, 2009Google Scholar

18. Josiassen RC, Ashok J, Kohegyi E, et al: Clozapine augmented with risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:130–136, 2005Google Scholar

19. Clark RE, Bartels SJ, Mellman TA, et al: Recent trends in antipsychotic combination therapy of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: implications for state mental health policy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 228:75–84, 2002Google Scholar