Implementation of Mental Health Parity: Lessons From California

There is growing evidence that parity may be associated with small improvements in access to mental health services for people with private health insurance coverage and that cost increases are small when parity is implemented with managed care arrangements ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). An evaluation of Vermont's mental health and substance abuse parity law found that utilization of mental health services increased slightly in two health plans, although health plan payments for mental health and substance abuse services rose only 4% per member per quarter, or 19 cents per member per month ( 5 ). Limited cost and use effects were also observed in the Federal Employees' Health Benefits program ( 4 ). Although access to mental health services increased over time, these trends were evident for enrollees in all health plans, not just those affected by parity in the Federal Employees' Health Benefits program. In other studies, parity effects were concentrated among low-income individuals in smaller firms (50 to 100 employees) or among those with relatively mild mental health conditions ( 3 , 9 ). Among Medicare beneficiaries with a psychiatric hospitalization, insurance parity was associated with increased care after hospitalization ( 10 ).

Information about the beneficial effects of parity contributed to the passage of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in October 2008. This law substantially extends the 1996 federal parity law by providing full parity for mental health and substance abuse coverage, including benefit limits and cost sharing. The law provides parity to 113 million people, including 82 million in self-insured health plans that were exempt from state parity reforms ( 11 ). It applies to group health plans purchased by employers (including those that are self-insured) and exempts individual plans, plans for employers with 50 or fewer employees, and those that document an increase in actual total health care costs of 1% or more (2% in the first year).

Despite the generally positive findings of previous studies of parity, some doubts remain about issues related to implementation and compliance. These are reflected in the law's requirements for a report to Congress by the U.S. Department of Labor Secretary on compliance with the act and for a study by the Government Accountability Office that analyzes the impact of parity on health insurance coverage and costs.

Additional information about these issues, and the possible challenges for policy makers in implementing the 2008 federal parity law, may be learned from a study of California's experience in implementing its parity law. Because of its size and diversity of its population and health system, California may more closely approximate what may be experienced under a federal parity mandate and can offer insights to improve the implementation and effectiveness of benefit expansions at the national level.

California's parity law, implemented in 2000, requires plans to offer mental health coverage as part of health benefit packages and eliminate mental health benefit limits and cost-sharing requirements that are less comprehensive than those for physical conditions. The law covers all group and individual insurance plans (excluding self-insured health plans exempt under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act). The California benefit mandate is limited to nine mental health diagnoses: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, pervasive developmental disorder or autism, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. The mandate also covers serious emotional disturbance among children and adolescents.

The purpose of this study was to assess experiences with California's parity law, and this article discusses implications for the implementation of parity at the national level. The analysis is based on an extensive set of site visits, telephone interviews, and consumer and provider focus groups conducted during the first five years of California's parity law. This study identified three lessons: the need for increased oversight of health plans, the consequences of a limited diagnosis list, and the lack of consumer awareness of parity.

Methods

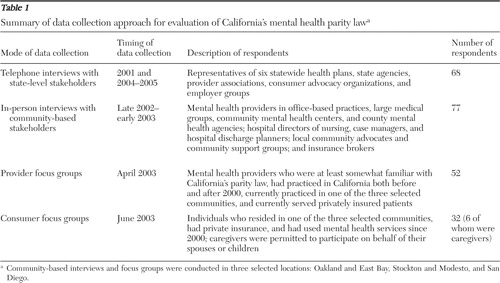

This study was conducted from September 2001 through January 2006, using a multimodal data collection approach that spanned nearly five years and provided comprehensive state and local perspectives on parity ( Table 1 ). A 14-person advisory panel reviewed the study design and analysis. The panel comprised California stakeholders (state officials, health plan medical directors, providers, and consumer advocates) and national experts (mental health services researchers and policy experts).

|

The interview protocols were based on a conceptual framework that depicted the roles and responses of state regulators, health plans, employers, providers, consumers, and the public mental health system. The protocols were tailored to the type of interview, but the core domains included respondent background information, awareness of parity, parity implementation activities, perceived effects of parity, satisfaction with parity, and areas for improvement.

A purposive sample of key informants was selected for the telephone and site visit interviews using referrals from staff of the state regulatory agency, state and county departments of mental health, and the state legislature; state trade associations representing health plans, mental health professionals, hospitals, and employers; and state and local chapters of mental health advocacy groups. To assess the responses of health plans to parity, interviews were conducted with six health plans that had 87% of all commercial enrollment as of July 2003 ( 12 ). Officials from five of the six plans completed a worksheet summarizing pre- and postparity mental health benefits and covered services for their most commonly offered benefit packages. State-level telephone interviews involved 68 respondents; the community-based site visits involved 77. Although the respondents are not strictly representative of all stakeholders statewide, their perspectives provide a comprehensive view of parity experiences.

Recruitment of providers for the focus groups was conducted by professional interviewers about three weeks before the focus groups; names were obtained from provider association mailing lists and health plan provider lists on the Internet. Consumers were recruited through providers who participated in focus groups and site visit interviews, direct mailings to consumer advocacy group members, and notices in newsletters sponsored by mental health advocacy groups, foundations, and associations.

Interviews with state-level stakeholders were conducted by telephone. Site visits and focus groups were held in three communities (Oakland and East Bay, Stockton and Modesto, and San Diego) representing diverse geographic areas that varied by urbanization, health plan coverage, per capita income, unemployment, and racial and ethnic composition. Two researchers participated in each interview using a semistructured discussion guide; one was responsible for taking notes, and the other reviewed and edited the notes as necessary.

Two provider and two consumer focus groups were conducted in each of the three communities. Discussions were led by an experienced moderator and facilitator who were guided by a semistructured protocol. The focus groups were conducted at hotels accessible to the freeway and public transportation and each lasted 90 minutes. An honorarium was provided to each participant at the end of the focus group ($100 for providers and $50 for consumers). The discussions were audiotaped and transcribed professionally. The moderator reviewed the transcripts for accuracy after transcription.

The 12 focus groups included 52 providers and 32 consumers (six of whom were family members). After the study was described to participants, informed consent was obtained before proceeding with the discussion. Institutional review board approval was not obtained because the study was an assessment of an existing initiative and there was no risk to human subjects.

The interview notes and transcripts were coded into 40 categories using ATLAS.ti . Research assistants were trained to perform the coding, and a researcher reviewed all transcripts to ensure completeness and accuracy of the coding and data entry. To develop key themes about stakeholder responses to parity and perceived effects, searches were performed in ATLAS.ti using keywords and Boolean terms. Case identifiers indicated respondent type and location to ensure that diverse responses were reflected in the analysis. This study focuses on key themes that have implications for the implementation of the 2008 federal parity law. A list of the full set of categories used to code interview notes and transcripts is available upon request.

Results

Health plan implementation of parity

The implementation of California's parity law led to changes in delivery systems, care management, and covered benefits. Four of the six health plans continued to use their existing mental health delivery systems, either carve-out arrangements with managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) or capitated medical groups. The other two transitioned mental health services from capitated medical groups to MBHOs.

Before the parity law, capitated medical groups reported that they managed mental health services by using explicit visit or day limits and ceased coverage once these limits were exhausted, whereas MBHOs employed medical necessity criteria to authorize services. Postparity, all health plans employ utilization management techniques, such as prior authorization of outpatient visits based on medical necessity determinations.

Table 2 shows pre- and postparity mental health benefits for commonly offered products for five of the six health plans. Preparity inpatient day limits varied widely, and 20 outpatient visits were typically covered per year. Postparity, all inpatient day and outpatient visit limits were removed for diagnoses covered by the parity law and copayments for parity diagnoses were made equal to those for medical services. Health plans reported that most benefit changes applied only to parity diagnoses, except for office-visit copayments. Health plans reported they did not apply different copayments for diagnoses that were not required to be covered at parity levels because it was difficult to establish whether patients had nonparity diagnoses when copayments were made.

|

Several health plans modified the types of services covered. One plan with relatively narrow preparity benefits added crisis intervention services and intensive, nonresidential treatment services as an alternative to hospitalization. Three plans covered nonhospital residential treatment before and after parity, whereas two plans did not offer such coverage either before or after parity. Prescription drug coverage did not change postparity because there were no preparity differences for medical versus psychiatric drugs.

Health plan representatives reported that insurance premiums for all health services increased by 10% or more per year over the first five years of parity, but they said they did not believe parity played a major role. These overall rates of increase are consistent with data published by the California HealthCare Foundation ( 13 ). Health plans consistently reported that cost increases after implementation of parity were in line with, or even below, preparity projections, and the level of increase depended on the generosity of preparity mental health benefits.

Increased oversight of managed care

One of the reasons for the modest cost increases in California is the use of managed care to control costs and utilization. The California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) oversaw the implementation of mental health parity by health plans. During the first five years the DMHC gave limited regulatory oversight and guidance, providing written clarifications about the law and promulgating regulations defining diagnoses and covered services. Monitoring was limited to meetings with stakeholders, analysis of consumer complaint data, and routine biennial health plan audits.

Over time, however, the DMHC increased its oversight of health plans in response to consumer and provider concerns about the limited regulatory oversight of access to care and lack of outcomes data. Specific concerns related to the use of medical necessity determinations to authorize treatment and the adequacy of health plan provider networks. Providers noted that capacity was especially limited for children's services and inpatient hospital beds ( 14 ). Many consumers also related experiences with "phantom lists" that include providers who were not taking new patients. Although some of these issues may have predated the parity law, they were highlighted by its implementation because of increased demand for mental health services. In response, DMHC promulgated new mental health access-to-care regulations and conducted focused studies of health plans along four dimensions: access and availability of services, continuity and coordination of care, utilization management and benefit coverage, and management of contracted MBHOs ( 15 ).

Consequences of the limited diagnosis list

The limited list of parity diagnoses emerged as a key implementation issue in California. Initially, the list was seen as a way to target benefits to individuals with biologically based conditions treatable through medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of the two without resulting in substantially higher costs. All health plan executives we interviewed said that, in retrospect, they do not believe a limited diagnosis list was necessary to make parity affordable. They spent considerable time and resources clarifying which diagnoses would be covered at parity. They indicated that use of medical necessity criteria would have enabled health plans to contain costs even if parity had been applied to all mental conditions. In practice, medical necessity was the primary driver for determining whether health plans authorized additional visits or days for parity and nonparity diagnoses. This was especially true for inpatient care, where nearly all consumers requiring hospitalization have parity diagnoses.

Many providers felt the parity diagnosis list was arbitrary in excluding certain diagnoses. They noted, for example, that distinctions between major depression, dysthymia, and depressive disorders not otherwise specified can be fluid, requiring clinical judgment based on consumers' symptoms and individual circumstances. The limited diagnosis list may have led to "upcoding" from less severe nonparity diagnoses to more severe parity diagnoses. Some providers reported that, although they strived to give an accurate diagnosis, they sometimes assigned a parity diagnosis to ensure that consumers had full coverage for their mental health services, even though the diagnosis may not have fit the patient exactly.

Some providers felt that the parity law left them with little flexibility to change a client's diagnosis if his or her condition improved or if a new condition developed because they believed that health plans would stop providing the same benefits if a less severe diagnosis was coded. Providers also raised concerns that those with less severe diagnoses may not have adequate access to the services that might prevent the onset of more severe conditions. One provider noted, "Without preventive care, you will become a parity diagnosis."

Lack of consumer knowledge of parity

Health plans, providers, and consumer advocates all pointed to the challenge of educating consumers about the parity law, such as explaining what services are covered and to whom the law applies. Initially, health plans provided written notification to purchaser groups and individual consumers about benefit changes. Subsequently, providers played a substantial role in ongoing education efforts, usually on a one-on-one basis with individual patients. Despite these efforts, consumer awareness about parity was limited. Nearly half of the consumer focus group participants (14 of 32 consumers, or 44%) indicated that they were not familiar with the law, even though most (26 of 32 consumers, or 81%) reported that they had a diagnosis covered by the law. Providers who participated in the focus groups indicated that many consumers lacked understanding of their mental health benefits; in other words, consumers did not know that their coverage was limited before the parity law or that it was expanded after the law was implemented. Providers indicated that many consumers perceived the law as complex and said that consumers would comment that they were uncertain how the law applied to their own circumstances.

When asked for their recommendations to improve the parity law, many consumers cited the need for additional education and information about parity. Some cited a role for employers and insurance companies, and others wanted providers to play a larger role. Some also recommended a concerted public information campaign: "Publicity … you know, signs in buses and billboards and that kind of thing. And public service announcements on television and radio."

Discussion

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results from this study. First, because information was gathered through in-person interviews, telephone interviews, and focus groups, there were no direct measures of the effects of parity on premiums and utilization. Second, this study had limited sample sizes, and respondents were not selected through a systematic sampling process. Whether these methods introduced selection bias is unknown, but the study attempted to minimize these concerns by obtaining a relatively large number of diverse perspectives over an extended period of time. Nevertheless, the perspectives presented in this study may not be representative of all California stakeholders—consumers, providers, and health plans—but rather may reflect the views of the stakeholders who chose to participate in the case study interviews and focus group discussions. Moreover, the perspectives may represent those existing at the time during which the qualitative data were collected and may not reflect more recent experiences.

This study found that the dominant health plans in California complied with the provisions of the parity law to eliminate disparities in mental health benefits ( 15 ). However, they used medical necessity criteria to control costs. Subsequently, state regulators recognized that compliance with the benefit requirements was but one step to achieving the objectives of the parity law. More regulatory oversight was instituted about five years after the initial implementation. In many respects, these implementation experiences mirror those in Vermont, where the legislature mandated new annual reporting requirements and quality standards for the five largest health plans operating in Vermont in order to increase accountability for health plan performance in delivering mental health and substance abuse services ( 5 ). The 2008 federal parity law mandates assessments of compliance, coverage, and costs; however, experiences in California (and Vermont) suggest that monitoring of health plan performance should include measures of access and quality, as well as coverage and costs.

The 2008 federal parity law also requires monitoring of health plans' exclusion of coverage for specific psychiatric and substance use diagnoses. Health plans may define which diagnoses they cover and are not prohibited from excluding coverage for a diagnosis. The experience in California suggests that a limited list of diagnoses may be unnecessary for cost-containment purposes, and such a list may produce unintended consequences, such as delays in seeking treatment, incentives for "upcoding" from less severe to more severe diagnoses, and a reversal of previous practice to assign the least severe diagnosis to avoid labeling and stigma. Health plan executives indicated that managed care arrangements and medical necessity determinations allowed for adequate cost containment under parity.

Finally, this study suggests that more proactive steps are required to improve consumer knowledge about parity. The limited awareness about parity in California was attributed to the lack of a systematic effort to inform consumers about the law. Similar results were observed in parity studies in Vermont and Maryland ( 5 , 16 ). An orchestrated education campaign in conjunction with the implementation of the 2008 federal parity law may increase awareness of mental health benefits and open the door to mental health services, especially for first-time users who may not be aware of their mental health benefits. Enhanced public education may also lead to reduced stigma associated with mental illness ( 17 , 18 ).

Conclusions

To maximize the effect of the 2008 federal parity law, experiences in California suggest that implementation of the federal law should include monitoring health plan performance related to access and quality in addition to coverage and costs, examining the breadth of diagnoses covered by health plans, and mounting a campaign to educate consumers about their insurance benefits.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration under contract 282-92-0021(27). The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this publication.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Barry CL, Frank RG, McGuire TG: The costs of mental health parity: still an impediment? Health Affairs 25:623–634, 2006Google Scholar

2. Branstrom BR, Sturm R: An early case study of the effects of California's mental health parity legislation. Psychiatric Services 53:1215–1216, 2002Google Scholar

3. Busch SH, Barry CL: New evidence on the effects of state mental health mandates. Inquiry 45:308–322, 2008Google Scholar

4. Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, et al: Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. New England Journal of Medicine 354:1378–1386, 2006Google Scholar

5. Rosenbach M, Lake T, Young C, et al: Effects of the Vermont Mental Health and Substance Abuse Parity Law. DHHS pub no (SMA)03-3822. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2003Google Scholar

6. Sturm R, Goldman W, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse parity: a case study of Ohio's state employee program. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 1:129–134, 1998Google Scholar

7. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533–1537, 1997Google Scholar

8. Zuvekas S, Rupp A, Norquist G: Special report: the impacts of mental health parity and managed care in one large employer group: a reexamination. Health Affairs 24:1668–1672, 2005Google Scholar

9. Harris KM, Carpenter C, Bao Y: The effects of state parity laws on the use of mental health care. Medical Care 44:499–505, 2006Google Scholar

10. Trivedi AN, Swaminathan S, Mor V: Insurance parity and the use of outpatient mental health care following a psychiatric hospitalization. JAMA 300:2879–2885, 2008Google Scholar

11. Kuehn BM: Congress passes mental health parity. JAMA 300:1868, 2008Google Scholar

12. InterStudy: The Interstudy Competitive Edge, Part I, Managed Care Directory, Reporting Data as of July 1, 2003. St Paul, Minn, Decision Resources, 2004Google Scholar

13. California Employer Health Benefits Survey 2004. Oakland, California HealthCare Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 2004. Available at www.chcf.org/documents/insurance/HRETEmployerBenefits2004.pdf Google Scholar

14. Psychiatric Hospital Beds in California: Reduced Numbers Create System Slow-Down and Potential Crisis. Sacramento, California Institute for Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar

15. Mental Health Parity in California: Mental Health Parity Focused Survey Project: A Summary of Survey Findings and Observations. Sacramento, Calif, Department of Managed Health Care. Available at www.hmohelp.ca.gov/library/reports/med_survey/parity/sfor.pdf Google Scholar

16. Castellblanch R, Abrahamson DJ: What focus groups suggest about mental health parity policymaking. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 34:540–547, 2003Google Scholar

17. Corrigan P, Penn D: Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist 54:765–776, 1999Google Scholar

18. Penn DL, Corrigan P: The stigma of severe mental illness: some potential solutions for a recalcitrant problem. Psychiatric Quarterly 69:235–247, 1998Google Scholar