Patients' Perception of Possible Child Custody or Visitation Loss for Nonadherence to Psychiatric Treatment

Parenting is an important rite of passage and can be challenging under even the best of circumstances. Parents with severe mental illness face additional challenges, such as increased risk of socioeconomic difficulty, marital discord, isolation and homelessness ( 1 , 2 , 3 ), impaired parent-child relationships ( 3 , 4 ), and children with mental illness and behavior problems ( 4 , 5 ).

Parents with severe mental illness may also have concerns (rightly or wrongly) that their illness may jeopardize their custody or visitation rights with their children. There are no formal practice standards to assess parental mental health or parental fitness ( 6 ), and it has been suggested that some parents may lose custody or parental rights without an adequate assessment ( 7 , 8 ). The literature, which is focused on mothers, indicates that the risk of losing child custody or parental rights may be as high as 60% ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). However, these studies are largely composed of mothers who are severely, chronically ill and impaired (and often psychotic); they are also limited to single programs or discrete regions within a state.

There is evidence that for at least some parents, stigma and fear of losing child custody resulted in delaying needed treatment ( 14 ). Such concerns among parents may also have a significant impact on treatment adherence or the therapeutic alliance. Therefore, from a clinical and policy perspective, in order to better serve parents with severe mental illness, it is important to understand whether the possibility of losing child custody or visitation is a common perception.

A survey of patients treated in publicly funded community mental health centers from multiple regions across the United States recently found that various tools are commonly used to facilitate treatment engagement or adherence ( 15 ). For example, patients may be told they must attend treatment to receive or keep housing or to receive their disability checks from their representative payees. It is unknown whether or how frequently child custody or visitation is used as a tool to encourage adherence to mental health treatment.

This pilot study used previously unreported data from the above-mentioned study ( 15 ) to explore how common it is for parents treated in public mental health settings to perceive that they are at risk of losing custody or visitation of their minor-age children if they are not adherent to treatment. It differs from prior literature in that it reports parents' perceptions of this possible risk over the previous six months, rather than measuring its actual prevalence. Further, we sampled a broad spectrum of parents served in the public sector and in multiple regions of the country. It also extends prior literature by reporting the perceived source of the concern—for example, state welfare agencies, courts, mental health professionals, or family members.

Methods

The data set has been described previously ( 15 ). In brief, 1,011 patients from publicly funded mental health programs were sampled from five sites: Chicago; Durham, North Carolina; San Francisco; Tampa, Florida; and Worcester, Massachusetts. Different recruitment strategies were used because of constraints imposed by the institutional review boards that approved the study at each site: sequential recruitment from the waiting rooms, random selection of patients from management information systems, or both. All participants gave written, informed consent to participate in the study interview and were paid $25. The interviews were conducted from October 2002 to December 2003.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined by chart review; the remaining information was obtained by participant self-report. Participants were asked whether they had used any alcohol, nonprescribed drugs, or drugs of abuse in the past 30 days. For those who responded yes, follow-up questions were asked that had been adapted from the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) and the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) ( 16 , 17 ). Participants were dichotomized into groups according to whether they had at least one self-reported symptom of problematic substance use or whether they endorsed none. The anchored version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was used to assess current psychiatric symptoms ( 18 ). Current function was assessed by the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ( 19 ). The Insight and Treatment Attitudes questionnaire (ITAQ) ( 20 ) was used to assess insight to mental illness. Interviewers at each site participated in an intensive two-day training session in reliable administration of the interview. For example, across the five sites there was 91% agreement (within 10 points) between interviewers and an experienced psychiatrist for total scores on the BPRS (out of a total of 84 possible ratings).

As part of the sociodemographic information obtained on all participants, we asked participants whether they were parents. Those who indicated "yes" were further asked whether they had children younger than 16—that is, minors. Parents were not asked whether the children lived with them. In this study, we report on the responses of participants who reported being the parents of minor children. Using separate questions for medications and mental health visits, participants were asked, "In the past six months, did you feel that if you did not keep your appointment at the mental health center or clinic [take your prescribed medications for mental health, alcohol, or drug problems] someone would try to take your children from your custody or stop you from seeing them?"

Parents responding yes were then asked open-ended questions about who made them feel this way; interviewers were instructed to ask for clarification if necessary. The interviewers coded responses at the time of the interview into the following categories: someone from the Department of Social Services, someone from the legal system, someone from the mental health system (for example, a case manager or psychologist), a family member, the patient himself or herself, or someone else.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine possible associations between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and perceptions of the risk of losing custody or visitation. Chi square tests were performed for categorical variables, and t tests were performed for continuous variables.

Results

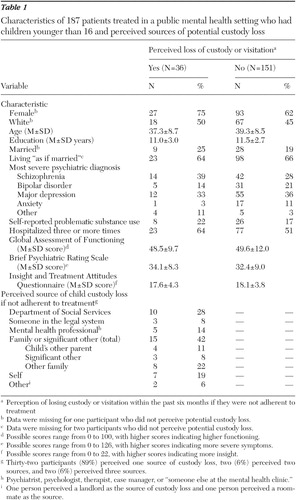

Among the 206 parents of minors, one refused to answer, five responses were missing, 11 responded "not applicable," and two responded "don't know." Of the final sample (N=187), 36 (19%) perceived in the prior six months that they might lose child custody or visitation if they did not adhere to treatment. There were no statistically significant differences in the sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between the parents with minor children who did and did not have this perception ( Table 1 ).

|

Most of the 36 parents (32 parents, or 89%) reported perceiving this pressure from a single source ( Table 1 ). Family members were perceived as the most prevalent source (42%), followed by the Department of Social Services (28%). Nineteen percent described the pressure as coming from themselves.

Discussion

Nearly 20% of parents in the publicly funded programs studied here perceived that they might lose child custody or visitation if they were not adherent to treatment. However, compared with prior studies of actual custody loss, the proportion of participants in our study who perceive this risk was low. One possible explanation is that parents who had already lost custody and were not regularly involved in their children's lives may have responded "no" to perceiving this risk in the past six months (because the loss had already happened). Also, our study sample was more diverse diagnostically and geographically than those in prior studies of actual custody loss, further making direct comparisons with prior literature difficult.

Many respondents who reported this perception identified family members as the source. Prior qualitative research has described the presence of this less formal source of pressure ( 12 ). Possibly, some clinicians suggested that the family members exert this pressure, rather than the clinician's doing so directly, in an attempt to foster a therapeutic alliance between clinician and patient. Approximately 20% of those who perceived this pressure reported themselves as the source. This may be a reflection of their fears (or insight), or they may have received explicit pressure by family or professional or legal sources in the past and believed it to continue. Future studies should examine this further.

This analysis has several limitations. Although we found no statistically significant sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between the parents of minors who did and those who did not perceive this risk, the study is underpowered for such analyses. The relationship between treatment adherence and parenting adequacy was not assessed, so we cannot comment on whether this pressure, if applied, was done so under appropriate circumstances. Contextual issues such as the current custodial or visitation status, conflicts in the marital or co-parent relationship, or involvement by a child welfare agency or the courts were not explored. Thus these results should be considered preliminary and suggestive of directions for future research. Last, our results cannot be considered to represent a national average: the sites were not randomly selected, and variations of a common approach were used for sample selection. Further, the patient demographic and clinical characteristics differ significantly among the five sites ( 15 ). However, to our knowledge there are no other studies that assess the perception of this risk by a full spectrum of parents treated in publicly funded mental health centers located in multiple regions around the United States.

Conclusions

Little is known regarding the clinical, functional, and quality-of-life effects on patients or their children of the fear of losing custody (either perceived or actual), despite the far-reaching effects it may have on a family. Although our results are preliminary, we found that among parents with psychiatric illness treated in publicly funded community settings, the perception that child custody or visitation may be lost if they are nonadherent to treatment is not rare and that family members are often perceived as its source. Thus future research should include these "less formal" sources of potential pressure, in addition to the legal or treatment systems, when attempting to capture the full picture of how perceived risks of losing child custody or visitation affect patient treatment seeking, adherence, and outcomes. Additionally, further research is needed to examine the clinical, functional, and psychosocial characteristics of patients who perceive and receive such pressure, how these characteristics differ when the source is from the legal or family system, and the effects on patient and family outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment. Additional funding was provided for Dr. Busch by grant K01-MH-071714 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors also thank Haiden A. Huskamp, Ph.D., Thomas G. McGuire, Ph.D., and John Monahan, Ph.D., for their helpful comments on this article.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Dennis D, Buckner J, Lipton F, et al: A decade of research and services for homeless mentally ill persons: where do we stand? American Psychologist 46:1129–1138, 1991Google Scholar

2. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:50–76, 1990Google Scholar

3. Oyserman D, Mowbray CT, Meares PA, et al: Parenting among mothers with a serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:296–315, 2000Google Scholar

4. Weissman MM, Feder A, Pilowsky DJ, et al: Depressed mothers coming to primary care: maternal reports of problems with their children. Journal of Affective Disorders 78:93–100, 2004Google Scholar

5. Warner V, Weissman MM, Mufson L, et al: Grandparents, parents, and grandchildren at high risk for depression: a three-generation study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:289–296, 1999Google Scholar

6. Otto RK, Edens JF: Parenting Capacity in Evaluating Competencies: Forensic Assessments and Instruments. Edited by Grisso T, Borum R, Edens JF, et al. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2003Google Scholar

7. Benjet CL, Azar ST, Kuersten-Hogan R: Evaluating the parental fitness of psychiatrically diagnosed individuals: advocating a functional-contextual analysis of parenting. Journal of Family Psychology 17:238–251, 2003Google Scholar

8. Ackerson BJ: Parents with serious mental illness: issues in assessment and services. Social Work 48:187–194, 2003Google Scholar

9. Sands RG, Koppelman N, Solomon P: Maternal custody status and living arrangements of children of women with severe mental illness. Health and Social Work 29:317–325, 2004Google Scholar

10. Coverdale JH, Aruffo JA: Family planning needs of female chronic psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1489–1491, 1989Google Scholar

11. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502–506, 1996Google Scholar

12. Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL: Focus on women: mothers with mental illness: II. family relationships and the context of parenting. Psychiatric Services 49:643–649, 1998Google Scholar

13. Hearle J, Plant K, Jenner L, et al: A survey of contact with offspring and assistance with child care among parents with psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:1354–1356, 1999Google Scholar

14. Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL: Focus on women: mothers with mental illness: I. the competing demands of parenting and living with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:635–642, 1998Google Scholar

15. Monahan J, Redlich AD, Swanson J, et al: Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services 56:37–44, 2005Google Scholar

16. Skinner HA: The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors 7:363–371, 1982Google Scholar

17. Selzer ML: The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry 127:1653–1658, 1971Google Scholar

18. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

19. Moerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:112–117, 1988Google Scholar

20. McEvoy J, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Insight into schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:43–47, 1989Google Scholar