A Family Psychoeducation Group Program for Chinese People With Schizophrenia in Hong Kong

As the trend moves toward community care, more than 50% of people with schizophrenia live with or depend on the care and assistance of their families ( 1 ). In such cases, the entire family may have to carry a heavy burden and undergo emotional distress in caring for the relative with schizophrenia. Recognizing the stress that such care imposes on family members, recent studies in the United States and the United Kingdom have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of a few models of family intervention, such as the family psychoeducation program and behavioral family management ( 2 , 3 ). The results of controlled trials that have examined the effectiveness of psychoeducational or behavioral models have been inconsistent and inconclusive, apart from showing improvements in the relapse rate and medication compliance of patients ( 3 , 4 ).

In addition, most family intervention studies have focused only on Caucasian populations ( 2 , 4 ). Only a few studies have been carried out with Chinese or Asian populations, in which great importance is attached to intimate interpersonal relationships and interactions with family members ( 5 , 6 ). Thus little is known about whether existing models of family intervention can be applied successfully to a Chinese family-oriented culture. In an attempt to address the specific educational needs of Chinese families, a new needs-based educational treatment model for schizophrenia, the family psychoeducation group program, has been developed. This program was developed on the basis of the results of a controlled trial of a family psychoeducation group intervention in Hong Kong ( 1 ). The study results highlighted the importance of a family needs assessment, the encouragement of peer support between participants, and adequate staff training and ongoing supervision for program operation—all of which became integral parts of the psychoeducation program that was evaluated in the study presented here.

The pilot study presented here was conducted to evaluate the effects of the psychoeducation group program on families of Chinese patients with schizophrenia recruited from two outpatient clinics in Hong Kong. It considered the program's effects on improvements in families' burden of care and functioning and on patients' functioning, symptoms, and rehospitalization rates, compared with changes among those who received standard care alone.

Methods

The study was a randomized controlled trial that used a repeated-measures design. It was undertaken between January 2004 and December 2005 and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the outpatient clinic. A total of 200 Chinese family members who were caring for a relative with schizophrenia who attended one of the two regional outpatient clinics were eligible for the study; the 200 relatives with schizophrenia were also eligible for the study. The 200 relatives with schizophrenia made up 5% of the outpatients with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Of these 200 family members, 150 of them (75%) agreed to participate. Of these, 84 (56%) were randomly selected to take part in this study. On the basis of previous studies of family psychoeducation groups among Chinese populations ( 6 , 7 ), this sample size was required to detect any significant difference between the groups at a 5% significance level with a power of 80% ( 8 ), taking into account potential attrition of 20%.

Family members were eligible to participate in this study if they were at least 18 years old, were free from any psychiatric disorder, and lived with and cared for a relative who at recruitment had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria. Family members were excluded if they cared for more than one relative with a chronic mental or physical illness, because they may have had different varieties and levels of demands regarding caring for the patients, which might not have been addressed by the psychoeducation program. After written consent had been obtained from the family members and their relatives with schizophrenia and after a full explanation of the study, they were randomly assigned to the standard care group (routine psychiatric outpatient and family services only) or to the psychoeducation group (participation in the family psychoeducation group program plus usual care). Patients also participated in parts of the psychoeducation program, such as the six educational sessions on the mental illness and its symptoms and the effects of medications.

The psychoeducation group program consisted of 18 sessions; each session met every other week and lasted about two hours. The treatment program consisted of four stages that were based on the work of McFarlane ( 3 ): orientation and engagement (three sessions), educational workshop (six sessions), therapeutic family role and strength rebuilding (seven sessions), and termination (two sessions). Patients participated in the six sessions of educational workshop. The program content was selected on the basis of the results of a needs assessment of 180 family members of Chinese persons with schizophrenia ( 9 ). The program used a culturally sensitive family intervention model, which considered many of the cultural tenets that were taught by Confucius (for example, valuing collectivism over individualism and giving great importance during the needs assessment to family and kinship ties) in respect to family relationships and value orientation.

The group instructor was a registered psychiatric nurse who was trained in a three-day workshop that was held by a family therapist and the researchers. The instructor was provided with information about schizophrenia, the necessary skills to lead a family group, practice in leading a few sessions of a family education group and discussion after each session, and ongoing supervision meetings about the videotaped group sessions over the period of intervention. Care in the standard care group involved routine psychiatric outpatient and family services only (which were also provided to the psychoeducation group). These services consisted of monthly medical consultation and advice; individual nursing advice on community health care services; brief family education (two or three one-hour group sessions) on the patient's illness, medication, and treatment plan; and counseling provided by clinical psychologists if necessary.

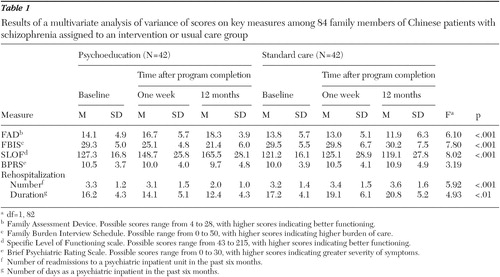

The two study groups did not differ in sociodemographic characteristics, medication types and dosages, or baseline measurement scores, according to the Student's t test or the chi square test. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed for the outcome variables to determine the treatment effects (group × time), followed by post-hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) analysis. One researcher, who was blinded to the participant allocation, administered the pretest before randomization and two posttests at one week and 12 months after completion of the intervention. Family functioning and burden of care were rated with the Family Assessment Device ( 10 ) and the Family Burden Interview Schedule ( 11 ), respectively. The symptoms and psychosocial functioning of the patients were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ( 12 ) and the Specific Level of Functioning Scale ( 13 ), respectively. The Chinese versions of these instruments were validated among Chinese patients with schizophrenia, indicating satisfactory reliability and validity ( 14 ). The patients' average number and length of rehospitalizations in the previous six months were calculated at the pre- and posttests. Data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis.

Results

Fifty-six of the 84 family members in this study were female (67%). Twenty-six (31%) family members were parents, and 25 (30%) were spouses. The mean age of the family members was 40.6±7.2 years (range=22–60), and 42 of them (50%) had completed secondary school or above. Their average monthly household income was H.K. $12,200 (U.S. $1,565). Fifty-one of the 84 patients were male (61%), and 50 of them (59%) had completed secondary school or above. The mean age of the patients was 28.8±4.8 years (range=20–49). Forty-eight family members (57%) had relatives who were taking second-generation neuroleptics (for example, clozapine and olanzapine). The average duration of the patients' illness was 3.6±1.8 years at recruitment (range=1–7). Forty-two participants were randomly assigned to the psychoeducation group, and 42 were assigned to the standard care group. Thirty-nine of the participants in the psychoeducation group (93%) completed the program, and four participants in the control group (10%) dropped out during the posttest period.

There was a statistically significant difference between the two study groups on the combined dependent variables (F=4.89, df=5 and 80, p=.005; Wilks λ =.98, partial η2 =.18). The mean scores and standard deviations and the results of a repeated-measures MANOVA for the dependent variables are shown in Table 1 . The results indicate that there were statistically significant differences over the follow-up period between the groups in improvement in family functioning and burden of care, patient functioning, and number and length of rehospitalizations in the past six months. The results of the Tukey's HSD test indicate that in the psychoeducation group family functioning and burden of care and number of patients' rehospitalizations improved significantly at the two follow-ups (one week and 12 months after completion of the intervention) but that patients' functioning and length of rehospitalizations in this program improved significantly only at the second follow-up.

|

Discussion

Similar to findings suggested in previous trials in Western countries ( 3 , 4 ), our findings demonstrate that providing a psychoeducation and supportive group intervention in a Chinese population in Hong Kong and addressing the specific cultural and family needs of persons who care for patients with schizophrenia (for example, strengthening the interdependence of family members in caregiving) may improve the psychosocial health condition of the entire family and their relative's risk of rehospitalization over a 12-month follow-up period. Nevertheless, as in previous studies of family group programs ( 2 , 3 , 4 ), it was too soon at one week after completion of the intervention to expect significant changes in patients' functioning and rehospitalization. Follow-up at one year or more would be required to identify the significant longer-term effects of a family psychosocial intervention. Because mental illness was a matter of great concern to most of the family members, it is noteworthy that they reported a significant improvement in their caregiving burden and functioning (such as communication with and attitude toward the patient). The reduced rehospitalization rates of the patients were probably due to better family support of patients' medication compliance and psychosocial functioning. In return, fewer patient relapses would likely result in better family functioning and health.

The significant positive results of the family psychoeducation program also demonstrate the need to consider such aspects as family needs assessment, staff training and continuous supervision, and peer support between family participants in the preparation and implementation processes. These components should be tested separately to confirm whether any of them would be an important factor for successful dissemination of family intervention, as suggested by previous studies ( 1 , 3 , 15 ).

The small size of the study group, however, limits analysis of the mediating variables to identify the therapeutic mechanisms of the psychoeducation group program. These mechanisms may have accounted for the improvements in the functioning of both the patients and the families who are involved in family-centered care for schizophrenia. Future research could use a larger sample, which would permit a deeper exploration of the relationships among the perceived benefits, the mechanisms of change, and the intervention techniques that are applied in a family psychoeducation group program.

Conclusions

This study supports the family psychoeducation group intervention to be an effective community-based intervention for family members of Chinese people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong, compared with routine psychiatric outpatient care. The small sample of Chinese families was recruited from two outpatient clinics in one geographical region. The group intervention was limited to nine months and no booster session was offered. These findings warrant further evaluation of this type of intervention and its therapeutic mechanisms and a comparison with other models of family intervention with larger representative samples of diverse sociocultural backgrounds and comorbidity of other mental problems.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant 2004-05 from the Nethersole School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The authors thank the outpatient clinic and its staff for their assistance in the recruitment of participants and data collection.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Chien WT, Chan SWC, Thompson DR: Effects of a mutual support group for families of Chinese people with schizophrenia: 18-month follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 189:41–49, 2006Google Scholar

2. Pharoah FM, Mari JJ, Streiner D: Family intervention for schizophrenia, in Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Issue 3, 2001. Oxford, Cochrane Library, 2001Google Scholar

3. McFarlane WR: Multifamily Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

4. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Fadden G, et al: Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention for families of patients with schizophrenia: results of a study funded by the European Commission. World Psychiatry 4:45–49, 2005Google Scholar

5. Li Z, Arthur D: Family education for people with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:339–345, 2005Google Scholar

6. Li Z, Arthur D: Family education for people with schizophrenia in Beijing, China: randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:339–345, 2005Google Scholar

7. Xiong MG, Ran MS, Li SG, et al: A controlled evaluation of psychoeducational family intervention in a rural Chinese community. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:239–247, 1994Google Scholar

8. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112:155–159, 1992Google Scholar

9. Chien WT, Norman I: Educational needs of families caring for Chinese patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Advanced Nursing 44:490–498, 2003Google Scholar

10. Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS: The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 9:171–180, 1983Google Scholar

11. Pai S, Kapur RL: The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry 138:332–335, 1981Google Scholar

12. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatric Reports 10:799–812, 1962Google Scholar

13. Schneider LC, Struening EL: SLOF: A behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Social Work Research 19:9–21, 1983Google Scholar

14. Chien WT, Chan SWC: One-year follow-up of a multiple-family-group intervention for Chinese families of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:1276–1284, 2004Google Scholar

15. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Malangone C, et al: Implementing psychoeducational interventions in Italy for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Psychiatric Services 57:266–269, 2006Google Scholar