Mental Health Care of Filipino Americans

With the constant influx of immigrants to the United States, providers are continuously challenged with how to best incorporate cultural factors when delivering mental health care to U.S. minority groups. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing minority group in the United States, making up 25% of the foreign-born population.

Asians generally exhibit cultural values that are different from those of Westerners ( 1 ). They have lower rates of divorce, crime, and juvenile delinquency. They have higher rates of educational attainments, higher family income, and more socioeconomic mobility. However, when it comes to providing individual mental health care for specific Asian populations, the generalization of grouping all Asians together falls short.

Asian Americans use less mental health care than any other minority group, regardless of age, gender, or geographic location ( 2 , 3 ). They drop out of treatment prematurely and tend to use services only during a crisis. Severe stigma associated with mental illness and a tendency to express psychological distress somatically continues to hinder Asian Americans from seeking care. Because of the diversity among Asians it is important to address the mental health issues of each group separately. Because there is a dearth of information on Filipino Americans, in this article we focus our discussion on this specific population.

History and demography

Filipino Americans constitute the second-fastest-growing Asian-American group in the United States, following Chinese Americans. Close to 2.9 million Filipinos reside in the United States, with the highest concentrations in California, Hawaii, and the East Coast. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts the population to be over four million by 2030. Foreign-born Filipino Americans outnumber U.S.-born Filipinos two to one.

Filipinos, known for their industriousness and upward mobility, have the highest rate of labor participation among all Asian groups, at 75.4%. Most Filipino Americans live with family members, and a third of families have more than five members. They have the highest rate of interracial marriages among Asian minorities, which influences acculturation, ethnic identification, and self-perception ( 4 , 5 ).

Filipinos were among the earliest U.S. immigrants. Records date their arrival to 1763, when seafarers jumped ship and settled in the Louisiana bayous. There followed four waves of migration, the largest happening after the adoption of the 1965 Immigration Act (PL 89-236), which abolished national origin quotas and permitted entry on the basis of family reunification and occupational characteristics. The Immigration Act brought about the influx of mostly educated, English-speaking, Filipino professionals, including physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals. This immigration continues even now.

History and intercultural influences combined to form Filipino core values and mold the Filipino psyche wherever they migrate. Precolonial records indicate that the Philippines had its own unique culture and social structure. Foreign occupation and subsequent liberations of the country have brought myriad traditions and customs. Foreign influence from the Spanish era, the American regime, and the Japanese occupation continue to blend with indigenous philosophy today.

Spaniards encouraged regionalism to dissipate nationalist revolt, practicing a "divide and rule" policy. Spanish friars inculcated Catholicism into Filipino customs and religious observances, lending to the preservation of native dialects and perpetuating a "colonial mentality." The U.S. occupation introduced the English language to Filipinos along with the American educational system.

Effects of regionalism

The Philippine archipelago has 7,107 islands and more than 60 cultural minority groups, each maintaining its individual identity. Its provinces are separated by water, and the larger islands are riddled with mountain ranges. About 80 to 100 ethnic languages exist, with the national language (Tagalog) spoken by a third of the population. "Tag-lish" (Tagalog and English), a hybrid language, is spoken by many. Language and ethnicity divides Filipinos and partially explains the regionalism that Filipinos bring when they immigrate ( 6 ). Depending on his or her ethnic subgroup, a Filipino may assume a different perception of mental illness that would influence that individual's approaches to ailments and treatments ( 7 ).

Filipino values of interdependence and social cohesiveness evolved from the group orientation necessary to live in the archipelago. This partly explains the hundreds of Filipino-American organizations in the United States. Geographic isolation, poor transportation facilities, and a meager economy foster reliance on extended-family systems and encourage outward relocation in pursuit of education and livelihood. Regionalism affects choice of residence, socialization, and patterns of organization of Filipinos in the United States ( 8 ).

It would seem that Filipino Americans, perceived as the most westernized of the Asian Americans, would be more apt to adapt to the American culture. However, they remain among the most mislabeled and culturally marginalized of the Asian Americans. Increased time of residence in the United States may not necessarily reflect an increase in the adoption of American lifestyle and culture ( 9 ). Studies of Filipino-American immigrants in Hawaii found that some immigrants effectively isolate themselves from American culture by electing to remain within Filipino groups, rarely associating with non-Filipinos ( 10 ).

Despite their numbers Filipinos are perceived as an "invisible" ethnic group, often mistaken for Latinos because of their Spanish-sounding last names, for Chinese because of their Asian features, or for African Americans because of their skin tone. This is exacerbated by the fact that many Filipinos tend to adopt a style of indirect verbal communication that might be confusing for non-Filipinos. It is sometimes challenging to know whether a Filipino is saying "yes" or "no" because of the abundant interplay of verbal and nonverbal cues that bewilder the listener ( 11 ). They receive fewer culturally based health and educational programs, because it is incorrectly assumed that they are all fluent in English.

Mental illness among Filipino Americans

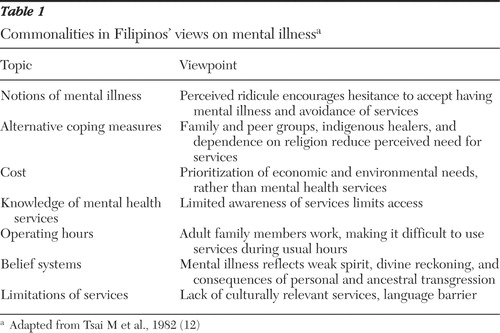

Lower socioeconomic and employment status, compared with that of other Asians, partly identified Filipino Americans as a high-risk group for mental disorders ( 5 ). Tsai and colleagues ( 12 ) enumerated commonalities in the behavior of Asian immigrants that affect perceptions of mental illness. Table 1 summarizes these commonalities on Filipinos' views on mental affliction.

|

The prevalence of depression among Asian patients in primary care settings is estimated to be around 14%, with higher rates among Filipinos, compared with Japanese and Chinese ( 13 ). This may still be underestimated because of the cultural tendency of Filipinos to deny, somatize, and endure emotional problems ( 14 ). Depression manifests in a variety of ways, from the classical symptomatology of excessive grief to the phenomenologically incongruous "smiling" depression. Nonetheless, the 2004 Surgeon General's report shows lower suicide rates among Filipinos (3.5 of 100,000) compared with those among whites (12.8 of 100,000) and other minorities ( 15 ).

In 1993 the Pilipino Health Task Force concluded that Filipinos in San Francisco lacked health care access because of their low utilization rate. Inadequate Filipino staffing was a barrier to provision of services. Having culturally and linguistically competent providers has been found to be associated with a lower level of need for crisis intervention and higher use of mental health services ( 16 ). Filipino Americans consistently show lower rates of treatment of mental illness. Those who utilize resources were found to be more severely disturbed than white Americans. McBride ( 17 ) found that in nine California Alzheimer's Disease and Diagnostic Centers, Filipinos accounted for only a small number of cases (.7%) of all persons screened in an eight-year period.

Separation from family and financial difficulties are common stressors among Filipinos with clinical depression. Among older Filipinos, men commit suicide at a higher rate than women, reflecting the trend among the general population of older Americans. Compared with other Asians, Filipinos were found to have a lower incidence of suicide because of the influence of Catholicism ( 17 ). Suicide rates may also be lower because of the available extended family and social support system.

In a study comparing Filipino-American and Caucasian opinions on causation of and treatments for depression and schizophrenia, Filipinos rated spiritual, personal, and social treatments as being more effective than did Caucasians. Filipino Americans considered interpersonal factors (time with family, friendship, and support groups) as important treatments for depression ( 18 ). Filipino Americans cited significant barriers to treatment, including dealing with family hierarchy and reputation, fatalistic attitude and religious fanaticism, lack of belief in one's capacity to change, communication barriers, externalization of complaints, and lack of culturally competent services ( 19 ).

Contributors to perceptions of mental health

Religion

Eighty-five percent of Filipinos are Catholic; almost everyone else is a member of a local church or a Muslim. Faith is practiced in a personal and tangible manner with strict adherence to religious rites. The importance of prayer and spiritual counseling cannot be overemphasized. Adversity is taken on without much effect on self-esteem because of one's faith. Filipinos tend to be passive and patient and are prone to being exploited, accepting suffering as a spiritual offering when events are perceived as being beyond their control.

A strong sense of religion focuses the Filipino toward alternative forms of medicine. During the precolonialist period and through most of the Spanish era, treatment of mental and physical conditions would involve rituals aimed at reversing punishment from the spiritual world and restoring balance in the physical world. These concepts were supplanted by a more biomedical approach as Western medicine was introduced during the American era.

Instead of going to physicians, many approach "albularyos" (faith healers). These indigenous healers use herbs, massage, oils, and prayer as treatments. Although these methods are "unscientific," people consult these faith healers partly because of the compassion they display, often in contrast to stereotypical Western-trained physicians.

Family and support systems

Filipinos are collectivists. Individual preferences are often overshadowed by group choices. They identify with their families, regional affiliations, and peer groups and are usually seen socializing in groups, especially in public places. Contemporary Filipino-American families function in a complex process of a natural support system of reciprocity and mutual caring to which the individual's concept of self is strongly subsumed. Concepts of group harmony, respect for elders, and kinship go beyond biological connections ( 20 ).

Mental illness is dealt with through the help of family and friends and faith in God. One's mental affliction is identified as the family's illness and is associated with shame and stigma. The open display of emotional affliction is discouraged in favor of social harmony. Assistance is often sought from relatives and peers before approaching professionals. Decisions, including health care practices and preferences, advance directives, and consent for procedures and treatment, are commonly made in consultation with the family.

Some families view children with mental illness as "bringers of good luck" ( 21 ). Filipinos willingly interact with persons with mental illness, but they may not accept them as cohabitants or employees. The rejection is based on the belief that persons with mental affliction are dangerously unpredictable ( 11 ). Filipinos generally unconditionally sacrifice time and vocation to accept and care for their disabled family members.

Economic necessity dictates taking on multiple jobs and partially explains the exceptionally high rate of Filipino women in the labor force. These women are at increased risk of health and psychological problems, because they are expected to work as well as retain primary responsibility for domestic tasks and child care ( 22 ).

Indigenous traits and coping styles

Indigenous Filipino traits, including "hiya" (devastating shame), "amor propio" (sensitivity to criticism), and "pakikisama" (conceding to the wishes of the collective), have been discussed at length in several references ( 14 ). The preoccupation with face-saving is fostered by the use of ridicule and ostracism in child training and often inhibits competitiveness, a trait valued in Western society. The resulting narcissistic wounding often leads to social withdrawal and isolation. "Bahala na" (optimistic fatalism), although initially a showing of a cavalier and "bring it on" attitude, runs contrary to proactive thinking, strategic planning, and a drive for advancement.

"Smooth interpersonal relationships" is the capacity to interact on an equal basis with others and is tied to the cultural characteristic of personalism (relating to individuals versus agencies or institutions). There is sensitivity for others, as well as respect, understanding, and consideration for others' limitations, which often conflicts with American openness and frankness. The tendency to have strong personalistic worldviews causes Filipinos to have difficulty in objectifying otherwise neutral life events. Emotional involvement often influences perceptions of others and can translate into self-esteem issues.

"Timbang" (balance) is central to Filipino concepts of health, just as balance is sought in all social relationships. Filipinos believe that health and happiness are the result of balance, whereas illness is the consequence of imbalance ( 23 ). The box on this page enumerates a range of beliefs pertaining to the influence of warmth and cold on the body.

Filipino beliefs about the body's balance and illness a

Rapid changes from hot to cold cause illness

Warm surrounding is essential to optimal health

Avoid cold food and drink in the morning

An overheated body is vulnerable to disease, a heated body can get "shocked" when cooled quickly, causing illness

A layer of fat maintains warmth, protecting the body's vital energy

Imbalance from worry and overwork create stress and illness

Emotional restraint is a key element in restoring balance

A sense of balance imparts increased bodily awareness and brings a holistic approach to health and illness

a Adapted from Becker G, 2003 ( 23 )

Filipinos' perceptions of their physicians determine preference of who provides care and how much trust is given. The concept of "hindi ibang tao" (one of us) versus "ibang tao" (not one of us) determines interactions between Filipinos and their health care provider. Those who exhibit respectfulness, approachability, and a willingness to accommodate the patient's need are considered to be "hindi ibang tao." Filipinos are reticent, concealing emotions and personal needs from people considered "ibang tao" ( 24 ). In cases where the provider is considered to be "ibang tao," Filipinos will hesitate to express feelings and emotions, expecting family members to intercede on their behalf, while responding politely to the provider at a formal, albeit superficial, level.

Traditional coping mechanisms include "tiyaga" (patience and endurance), which enables Filipinos to tolerate uncertain situations; having respect for and being honest with oneself; flexibility; "lakas ng loob" (inner strength and hardiness); humor; capacity to laugh at oneself in times of tribulation; and prayer. A common strategy employed is the creation of a pseudo-family. Filipinos draw together compatriots on the basis of home ties and strengthen their kinship through religious and cultural activities. Hospitality and generosity abound even in hard times, with trifling consideration for financial consequences.

These coping styles may impede the adjustment necessary in the task-oriented and more impersonal environment of the American workplace. Self-identity and individual growth are hampered, hindering the acculturation needed to adjust to the host society.

Clinical implications in treating Filipino Americans

A comprehensive cross-cultural assessment is the first step in treatment. Evaluations should include an immigration history, socioeconomic beginnings, and regional orientation, tracing the chronology of events that led to the visit, considering the family's conceptualization of the condition and course of treatment, and ascertaining health practices and fears for implications of treatment.

Filipinos' motivations and actions are intimately connected to their family's welfare and reputation. They are usually more comfortable discussing their illness and other important matters in the presence of family. There exists a natural culturally bound aversion to consulting providers about psychological issues, so a decision to seek help must be adequately explored.

Generally, gender preferences are overshadowed by compassion. It is more important to have a compassionate listener as a provider than to have someone of the same gender. Most Filipinos are shy about divulging personal matters. They will not readily show a lack of understanding toward the illness or proposed treatment. When explaining diagnosis and treatment, the physician should not readily accept a shy expression of acknowledgement because Filipinos may claim to understand even when they are at a loss simply to "save face." Embarrassment or respect may prevent them from asking relevant questions. Repeating oneself and soliciting understanding are advantageous.

Visual cues and written words facilitate understanding. Phrases connoting a collaborative relationship ("our aim is…" and "we are working on this…") are beneficial. Calling a Filipino patient by first name in an initial encounter may be considered inappropriate, especially with an older person. Inquiring about physical complaints before the psychiatric assessment facilitates open dialogue and builds rapport. Somatic measures that afford relief should be discussed while probing the patient's assumptions and beliefs about the condition.

Learn when to speak directly with the patient and when to communicate indirectly through family. Consultation with designated family members about a patient's condition may be as appropriate as approaching the patient directly. Patient's consent can be sought to preserve privacy and client autonomy, preventing embarrassment if issues are raised that are considered private. Identify persons of influence to the patient. These would usually be the same people accompanying the patient at the first visit and would also be involved in the patient's treatment. Allow for brief periods of silence or pauses in the conversation to enable the patient to process information that may be occurring in the native language, especially among those with limited language skills.

Filipinos value their personal space. Maintain a reasonable distance of one to two feet. Make brief and frequent eye contact at eye level. Some patients may look down or away as a sign of respect to an authority figure, and this does not necessarily mean disinterest or avoidance. Filipinos' emotional responsiveness and affect may be misleading. Some may smile inappropriately, although this could be a sign of nervousness or embarrassment or may reflect personal mannerisms. Head wagging (the unconscious movement of one's head) should not be confused with shaking one's head in disagreement.

Therapeutic interventions

Filipinos are quite accepting of pharmacotherapy. There may be an expectation of being given medications when visiting a practitioner. Because of a predilection of Asians to develop side effects at lower doses, the practitioner must "start low and go slow." Filipinos, just like other Asian minorities, respond to lower dosages and experience side effects at lower dosages of medications ( 25 ).

A usual approach of the patient is to try gaining familiarity and close affiliation with the psychiatrist. This sentiment needs elucidation without alienating the patient. Filipinos are generally less accustomed to a traditional psychotherapeutic stance, in which the therapist assumes a more passive and neutral approach. Active engagement with the patient is preferred.

Psychiatrists should not hesitate to assume a medical role. It may be helpful to use an initial authoritarian approach that conforms to the patient's conceptualization of the physician as a patron or expert. The patient may attribute the resolution of interpersonal conflicts to spiritual or family leaders, rather than to the physician. The physician needs to be cognizant of this and focus on relieving the patient's symptoms, rather than changing beliefs.

The box on this page summarizes our recommendations for clinicians involved in the treatment of Filipino Americans.

Guidelines for a culturally sensitive approach to treatment of Filipino Americans

Pay attention to immigration history and regional orientation

Determine the underlying reason for treatment

Ensure adequate understanding of the diagnosis and treatment plan, bearing in mind that social inhibitions and nonverbal cues can mislead the practitioner

Use visual cues and communicate in a collaborative manner

Facilitate dialogue, inquiring about physical as well as mental health complaints

Utilize the family and identify the patient's power hierarchy

Allow the patient time to process any information given

Respect personal space

Note mannerisms without making assumptions about their meaning

Do not be misled by the presenting affect

Maintain judicious use of medications

Engage the patient by actively focusing on the individual's symptoms

Conclusions

Increased priority to resources and a strategically coordinated network of social services that recognizes specific sociopolitical, economic, and cultural needs have to be in place when delivering mental health services to Filipino Americans. It is ideal to have such services within existing medical institutions and staffed by culturally sensitive medical, psychiatric, and social service personnel.

Psychiatrists need to embrace culture as a powerful factor in understanding the Filipino-American experience. A culturally sensitive and imaginative approach to the individual should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Sue S: Asian American mental health: what we know and what we don't know, in Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. Edited by Lonner WJ, Dinnel DL, Hayes SA, et al. Bellingham, Wash, Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University, 2002. Available at www.ac.wwu.edu/~culture/readings.htm. Accessed Dec 20, 2005Google Scholar

2. Lin KM, Cheung F: Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services 50:774–780, 1999Google Scholar

3. Sue S, Sue DW, Sue L, et al: Psychopathology among Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health 1:39–54, 1995Google Scholar

4. Yuchengco ML, Ciria-Cruz RP: The Filipino American community: new roles and challenges, in The Philippines New Directions in Domestic Policy and Foreign Relations. Edited by Timberman DG. New York, Asia Society, 1998. Available at www.asiasociety.org/publications/philippines. Accessed Feb 25, 2006Google Scholar

5. Sue S, Morishima J: Mental Health of Asian Americans. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1982Google Scholar

6. Tompar-Tiu A, Sustento-Seneriches J: Depression and Other Mental Health Issues: The Filipino American Experience. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1995Google Scholar

7. Reyes B, Della C: Revisiting the past: Philippine psychiatry through the years, in Beyond the Physical: The State of a Nation's Mental Health—The Philippine Report. Edited by Casimiro-Querubin ML, Castro-Rodriguez S. Melbourne, Australia, Centre for International Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

8. Espiritu YL: Colonial oppression, labor importation, and group formation: Filipinos in the United States, in Filipinos in Global Migrations: At Home in the World? Edited by Aguilar F. Quezon City, Philippines, Philippine Social Science Council, 2002Google Scholar

9. Brown D, James G: Physiological stress response in Filipino-American immigrant nurses: the effects of residence time, lifestyle, and job strain. Psychosomatic Medicine 62:394–400, 2000Google Scholar

10. Brown D: Physiological stress and culture change in a group of Filipino-Americans: a preliminary investigation. Annals of Human Biology 9:553–563, 1982Google Scholar

11. De Torres S: Understanding persons of Philippine origin: a primer for rehabilitation service providers. Buffalo, New York, Center for International Rehabilitation Research Information and Exchange, 2002Google Scholar

12. Tsai M, Teng L, Sue S: Mental status of Chinese in the United States, in Mental Health of Asian Americans. Edited by Sue S, Morishima J. San Francisco, Calif, Jossey-Bass, 1982Google Scholar

13. Kuo WH: Prevalence of depression among Asian Americans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:449–457, 1984Google Scholar

14. Araneta E: Psychiatric care of Pilipino Americans, in Culture, Ethnicity and Mental Illness. Edited by Gaw A. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

15. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

16. Ziguras S, Klimidis S, Lewis J, et al: Ethnic matching of clients and clinicians and use of mental health services by ethnic minority clients. Psychiatric Services 54:535–541, 2003Google Scholar

17. McBride M: Health and Health Care of Filipino American Elders. Stanford, Calif, Stanford Geriatric Education Center Stanford University School of Medicine, 2001. Available at www.stanford.edu/group/ethnoger/filipino.html. Accessed Jan 20, 2006Google Scholar

18. Edman J, Johnson R: Filipino-American and Caucasian American beliefs about the causes and treatment of mental problems. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 5:380–386, 1999Google Scholar

19. Pacquiao D: Overcoming stigma of mental illness among Filipinos. Presented at the National Conference of the New York Coalition for Asian Mental Health, New York Academy of Medicine, New York, Oct 1–2, 2004Google Scholar

20. McBride M, Parenno H: Filipino American families and care giving, in Ethnicity and the Dementias. Edited by Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Philadelphia, Routledge, 1996Google Scholar

21. Carandang ML: Filipino Children Under Stress: Family Dynamics and Therapy. Manila, Philippines, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1987Google Scholar

22. Siewert P, Jones L: Filipino American women, work and family: an examination of factors affecting high labor force participation. International Social Work 40:407–423, 1996Google Scholar

23. Becker G: Cultural expressions of bodily awareness among chronically ill Filipino Americans. Annals of Family Medicine 1:113–118, 2003. Available at www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/113. Accessed Nov 15, 2005Google Scholar

24. Pasco A, Morse J, Olson J: Cross-cultural relationships between nurses and Filipino-Canadian patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 36:239–246, 2004Google Scholar

25. Tseng WS: Clinician's Guide to Cultural Psychiatry. New York, Academic Press, 2003Google Scholar