Adding Consumer-Providers to Intensive Case Management: Does It Improve Outcome?

Case management has been the focus of a large body of research and is a treatment recommended by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team ( 1 ). A general conclusion from several recent qualitative literature reviews ( 2 , 3 ) and a meta-analysis ( 4 ) was that full-service models of treatment in which professional therapists provided in vivo services were consistently superior to "broker" programs in which services are arranged rather than provided. These full-service treatments, often referred to as intensive case management programs, exist in a variety of forms—for example, assertive community treatment and strengths-based treatment. These programs consistently proved effective in retaining patients in treatment, reducing time spent in the hospital, and increasing patient satisfaction with treatment. Few reviews found consistent evidence for reductions in symptoms, improvements in social functioning, and improvements in quality of life. Social isolation and loneliness continue to be a challenge for individuals with psychiatric disabilities, a challenge that may be met through peer support ( 5 , 6 ).

Over the past decade there has been increasing interest in the possible benefits of employing mental health consumers in various roles as providers of services ( 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). The addition of consumer-providers has been associated with reduced hospitalization ( 21 , 22 ) and greater client satisfaction, with a trend toward better social functioning ( 10 ). Consumer case managers had more face-to-face interactions ( 19 ) and placed much more emphasis on "being there" with the client rather than on accomplishing tasks ( 15 , 16 ). Integrating peer support with case management may improve quality of life and social functioning ( 3 ). Peers could provide social support that offers general friendship, reduces stigma, and builds hope, and they could provide recreational opportunities that are not otherwise available ( 23 ).

More research is needed to clarify the effects of consumers on service delivery, quality of life, and social functioning ( 5 ). The few randomized studies conducted have had significant methodological weaknesses, small samples, and nonstandard measures ( 24 ). With the exception of one study comparing consumer and nonconsumer assertive community treatment teams ( 22 ), studies employ integrated models of care in which the consumer role is poorly defined. It is not clear in previous studies whether consumers are representative of the populations they serve.

In order to better understand the effects of adding consumer-providers to intensive case management, this study randomly assigned clients with severe mental impairment to one of three treatment methods. The first type of treatment, consumer-assisted intensive case management, referred to as peer-assisted care in this article, links professionals and paraprofessional consumer staff in specific and complementary roles. Professional staff provided conventional crisis management, therapeutic services, and concrete services by using a strengths-based case management model. Paraprofessional consumers were responsible for facilitating social networks and providing social support through arranging activities, home visits, and phone calls. Our second type of treatment, standard care, offered strengths-based intensive case management without the peer enhancement. A third type of case management, referred to as clinic-based care, did not have peer enhancement and restricted all services to the office-based setting.

Consumers with severe mental impairment were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions between July 1997 and December 2000, and they were assessed on satisfaction, quality of life, social networks, and symptoms at baseline and at six and 12 months. It was anticipated that both of the full-service intensive case management services—peer-assisted care and standard care—would maintain the positive outcomes usually associated with standard intensive case management (that is, retention in treatment, patient satisfaction, and reduced hospitalization) and would show better outcomes than clinic-based care. Peer-assisted care was also expected to improve social networks, leading to positive changes in social functioning and quality of life.

Methods

Peer-assisted care was evaluated by comparing outcomes to those associated with standard care and clinic-based care. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment groups. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, six months, and 12 months.

Participants

The institutional review boards of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and of Elmhurst Hospital Center approved all study protocol and procedures before data collection, and informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants. A power analysis indicated that approximately 150 participants divided among three groups would be needed for the detection of a moderate group effect with 80% power at the .05 alpha level. To detect treatment by time interactions of moderate size, the same number of participants would yield 90% power at the .05 alpha level.

Research assistants recruited clients meeting inclusion criteria from inpatient units at a city hospital between July 1997 and December 2000. Participants were required to be older than 18 years, have a diagnosis of a psychotic or mood disorder on axis I, and have had two or more psychiatric hospitalizations in the previous two years. On inpatient units, 369 of 585 eligible clients consented to participate. Many consenting patients were subsequently excluded because they were discharged to alternative treatment settings, leaving 255 participants who were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment conditions. A total of 203 participants completed most measures to the 12-month follow-up, thus meeting our requirements for sufficient power for detecting moderate-sized effects.

Description of the treatment programs

All professional services in the standard care condition were provided by two licensed clinical social workers who were supervised by program directors with extensive experience in providing psychiatric rehabilitation services. Staff received 40 training hours and competency testing before working with clients. Staff also received one hour of individual supervision, one hour of group supervision, and 1.5 hours of training weekly for the duration of the project. Services were organized along the strengths model ( 25 ), with high fidelity to the various design elements ( 26 , 27 ). Care was provided individually with use of natural community resources and with backup from a team member. Caseloads were limited to 20 persons. A core element of the strengths-based approach is venerating the client ( 25 ). This means respect for the client's autonomy, focusing on the client's wants, and treating the client as a person rather than a case to be managed. The personalistic focus deemphasizes the role relationship and professional distance. The strengths-based provider may self-disclose more, socialize with the consumer, and spend more effort on building the relationship. Key exceptions to the strengths-based approach were that 24-hour coverage was telephone-based and that all clients were encouraged to participate in cognitive-behavioral group therapy structured on a social skills model ( 28 ).

Peer-assisted care was provided on the same basis as the standard care model except for the consumer enhancement. One full-time social worker and one half-time social worker supervised four half-time consumer-providers (peers). We recruited peers who matched the demographic characteristics and treatment profile of participants in order to maximize affinity with the consumers. Peers had a history of multiple hospitalizations for mood or psychotic disorders, were eligible for disability benefits, and relied on medication for stability. Peers typically had three to eight years of sobriety and stability in the community and were recruited from vocational training and peer advocacy programs. They participated in the same orientation and training as professional staff, with modifications to address their specific roles. They were supervised by the full-time social worker, who met with them individually and in groups to solve problems with the engagement of clients and to plan activities.

The peers engaged clients in social activities and developed supportive social networks among clients. They planned one-on-one and group social activities in and around clients' homes and other community locations. For example, a peer might regularly meet a client for coffee to develop a relationship. Later, that client might be invited to a group activity or to come with the peer to visit another client. Ideally, the peer would facilitate independent relationships between the clients. Peers were instructed to focus on relationship building around the interests of participants by using natural community resources. They took extensive advantage of libraries, churches, civic associations, and museums, as well as a rich array of cultural events available in our community. They followed the preferences of participants in planning activities. They were instructed not to provide routine case management services. Peers also contributed to treatment planning and provided valuable information about participants during weekly team meetings.

Clinic-based care was provided by a doctoral-level psychologist and a clinical social worker by using the same strengths-based treatment approach that was used in standard and peer-based care. All services were provided in the clinic, and 24-hour telephone coverage was not available to this group.

Measures

The measures fall into three categories: services, social network measures, and outcome measures—that is, satisfaction with services, quality of life, and symptoms.

Services. Several dimensions of services were assessed by using interviews and hospital records. By using a self-report instrument developed by Clark and colleagues ( 29 , 30 ), clients were interviewed monthly throughout treatment on recent contacts with health services to determine outpatient contacts per month for medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse problems. We systematically examined all hospital records to derive objective measures of group therapy, individual therapy, and social activity in hours per month and hospitalization days per month.

Social network measures. Changes in the participants' social support network were evaluated with a modification of the Pattison Network Inventory ( 31 , 32 ). This interview assessed social network size, total number of social contacts, degree of reciprocity of relationships, density of the social network, and the number of times the client was helped or had helped others in his or her network.

Outcomes. Outcomes were measured along several dimensions of satisfaction, quality of life, and symptoms. The Behavioral Health Care Rating of Satisfaction was used to index client satisfaction with the clinical staff and services ( 33 ). Subjective and objective dimensions of quality of life were measured by the Lehman Quality of Life Inventory ( 34 ). To measure clinically relevant symptoms, the Brief Symptom Inventory was employed ( 35 ).

Procedure for recording, managing, and analyzing data

Research assistants who were blind to the treatment assignments collected all interview data, except for the social network measures, which were collected by the professional staff. Hospitalization and service data were collected from multiple sources: interviews, various hospital databases, and the clinicians' records.

Data were entered into a secure database by using unique identification numbers for participants. Each variable was recorded at baseline, six months, and 12 months. SPSS software was used to manage and reduce the raw data and to calculate descriptive and inferential statistics. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance were employed to assess group differences between treatment conditions at baseline and differential effects of the treatment conditions over time. Missing data contributed to small variations in sample sizes for the analyses of network and outcome variables.

Results

The sample size was reduced from 255 to 203, mostly because some clients were discharged to long-term residential programs that would not allow enrollment in our clinic. Analyses of baseline data indicated no differences between clients who remained in the study and those who did not. Furthermore, there were no differences among the three treatment groups at baseline for the service, network, and outcome measures.

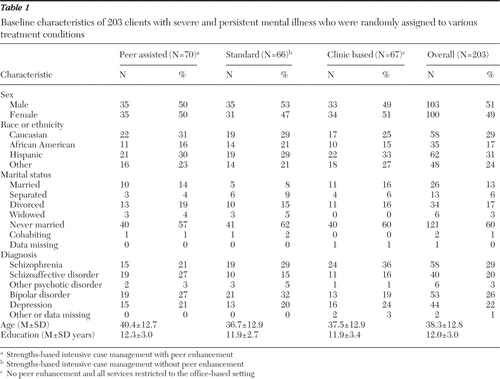

The 203 participants are described in Table 1 . There were no significant differences between treatment groups at baseline on the following variables: sex, race or ethnicity, age, education, marital status, and diagnosis.

|

Services

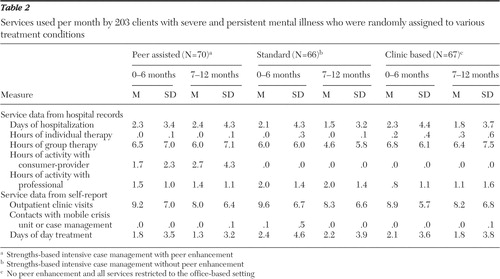

Table 2 displays group means and standard deviations for all of the services and cost variables at the six- and 12-month follow-ups. Note that only clients receiving peer-assisted care had contact with consumer-providers, and this contact increased over time (t=-2.52, df=69, p=.01). For all other service variables, a condition (three groups) × time (six and 12 months) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant interactions. In other words, any observed changes over time were similar across the three treatment conditions.

|

Clients receiving clinic-based care accumulated more individual therapy hours per month compared with the other two conditions (Duncan post-hoc test, p<.05). On the other hand, clients who received standard care received the most time with the professional staff in organized activities (Duncan post-hoc test, p<.05). All conditions showed a significant decrease in group therapy and outpatient services over time (p<.05 for both effects).

We performed an additional analysis to see if the number of hospitalizations per month changed from the six-month interval before treatment to the 12-month interval after treatment. Across the sample of 203 clients, there were 4,261 hospitalization days in the six-month interval before treatment, corresponding to a monthly average of 3.50 per client. After treatment started, this average dropped to 2.24 from baseline to six months (2,725 hospitalization days) and to 1.89 from seven to 12 months (2,304 hospitalization days). These data represent a 46% decrease in hospitalizations across 18 months. A treatment condition (three groups) × time (baseline, six months, and 12 months) repeated-measures ANOVA showed only a main effect of time (F=12.92, df=2 and 400, p<.01, η2 =.06).

Network measures

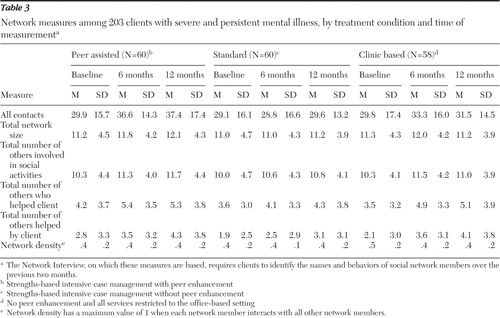

Table 3 displays the means and standard deviations for the primary network measures across three times (baseline, six months, and 12 months) for each of the three treatment conditions. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of treatment over time for the measure of total social contacts. Only clients receiving peer-assisted care showed a significant increase in the number of contacts from baseline to 12 months (simple effect: F=7.25, df=2 and 118, p<.01, eta2 =.11). Follow-up analyses revealed that this effect was due to increased contact with peer assistants and professional staff, not with family and outside friends. There were also significant improvements for all conditions in several other network measures as indicated by reliable main effects of time: total number of others involved in social activities, total number of others who helped client, total number of others helped by client, and network density (p<.05 for all effects).

|

Outcome measures

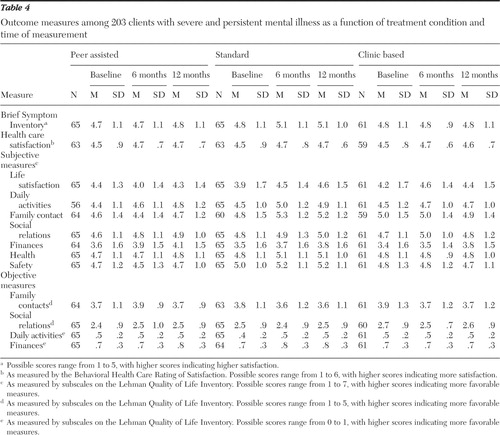

Table 4 displays the means and standard deviations for 14 outcome variables: symptoms, satisfaction with health care, subjective ratings of quality of life in several domains, objective ratings of contacts with family or friends, and objective ratings of activities and finances. Analyses of covariance were used to assess the effect of treatment condition on the 14 outcome measures at 12 months, with the corresponding baseline measurement as a covariate. None of these analyses yielded significant findings, indicating that all three treatments yielded similar outcomes. To assess changes in outcome measures over time, a repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on each of the 14 measures over three time periods (baseline, six months, and 12 months). Results indicated reliable improvements in outcomes for seven of the 14 measures: Brief Symptom Inventory scores, health care satisfaction, subjective daily activities, subjective social relations, subjective finances, objective daily activities, and objective financial adequacy (all p values less than .05).

|

Discussion

Our data indicate that although the three programs had distinct patterns of services, they yielded the same general pattern of improvement over time on a variety of measures: symptoms, health care satisfaction, and various ratings of the quality of life. Clients in the three programs also showed similar but small changes in measures of social network behavior. The peer-assisted care condition was unique in its use of peer-organized activities. The standard care condition made greater use of individual contacts with professional staff. The clinical care condition, providing largely office-based services, relied more on group and on individual therapy, compared with the other two conditions. Despite these variations in the pattern of services over a 12-month period, no one program emerged as categorically superior to the others.

All of the treatment conditions gave evidence of improvement in social networks over time. As expected, peer-assisted care showed the greatest increase in self-reported social contacts with consumer and professional staff. Peer assistants provided planned activities and regularly scheduled home visits to enhance the social network. These increases did not extend to kin social contacts, consistent with previous research on the stability of social networks of persons with severe mental impairment ( 36 , 37 ). Although the work of peers enhanced the social networks of consumers, this did not translate into measurable changes in treatment outcome.

An unexpected finding was that consumers in clinic-based care showed the same improvements in outcomes over time as the other two groups. We think that the robustness of the strengths-based approach underlying all care at our institution is partly responsible for this result. All conditions received cognitive-behavioral group therapy supplemented by individual therapy provided by well-trained clinicians. Although the clients in clinic-based care did not receive home visits, the case management was still held to a high standard of care and follow-up because of the high-risk nature of the population served. As a result all groups showed improvement over time across a variety of subjective and objective measures, including symptoms, general life satisfaction, and income. Nonetheless, one may argue that lacking a true control group, these changes over time could have been due to selection of clients at a time of particularly low functioning or due to another uncontrolled effect of history. The robust changes that we observed across a broad array of measures seem more consistent with a true overall effect of case management.

Given the evidence for comparable improvements across the three types of treatments, and the lack of distinct effects of consumer-assistants on satisfaction and symptoms, the question is raised as to whether the behaviors of the provider are more important than who provides the service. In developing our consumer-assisted case management condition, careful attention was paid to defining a clear role that would capitalize on the unique benefits of peers working from a personalistic perspective. Peers focused on socialization and support. They geared all interactions toward relationship building and engagement. They refrained from providing other therapeutic services to consumers. From the perspective of job design, personal history, and status as peers, we expected that peers would be superior to professionals in the implementation of relationship-based interventions. Peers would bring to the table their unique perspectives, social affinity, and a freedom to engage consumers at a personal level that professionals generally do not have.

On the other hand, all staff—peers and professionals—were trained and supervised to work from a personalistic perspective by using the strengths-based model. Professional staff acted to reduce personal distance, crossed boundaries in appropriate ways, socialized with clients, self-disclosed, and generally acted to form strong relationships with clients. In the social network measures, consumers listed professional staff as members of their network at the same rate as they claimed peers as members. More research is needed to assess exactly what behaviors make consumers effective in service delivery and whether those behaviors are necessarily unique to consumers.

A major challenge for future studies is to identify an optimal role for consumer-providers ( 38 ). In many service delivery models, the lack of a specific role may lead toward peers performing more menial and less clinically oriented tasks, such as escorting or locating patients who miss appointments. In other cases, the professionalization of peers may reduce the specific benefits of having consumers as providers. Although the study presented here has a well-defined role for consumer-providers, using peers whose clinical profiles are similar to the consumers they serve, it did not exhaust all of the possible roles for consumers in case management service delivery, including training in illness management using nonmedication methods or recovery groups. Our research design did not address whether consumers could be trained to assist individuals in using natural community resources to enhance existing or informal networks ( 5 ). Research is needed to assess what qualities, training, and support are needed to ensure that peers are successful in their roles.

Conclusions

Bringing consumers into all aspects of mental health care remains a laudable agenda. We have not addressed the value of consumer involvement in service delivery from a systems-change perspective nor the benefits for the consumers providing services. Nevertheless, we have shown that a fairly robust randomized trial of real-world treatment delivery with a well-defined role for consumers that capitalizes on their theoretical strengths has not found evidence that consumers enhance case management.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by funds furnished by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the New York State Office of Mental Health, and the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation. This article has not been officially reviewed or cleared by any of the funding sources.

This article is based on the work of the late Jeffrey R. Bedell, Ph.D., and Neal L. Cohen, M.D. The authors thank Jack M. Gorman, M.D., for invaluable guidance.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, Dixon LB, et al: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patients Outcome Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Google Scholar

2. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Google Scholar

3. Bedell JR, Cohen NL, Sullivan A: Case management: the current best practices and the next generation of innovation. Community Mental Health Journal 36:179–194, 2000Google Scholar

4. Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, et al: Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:443–450, 2006Google Scholar

5. Davidson L, Shahar G, Stayner DA, et al: Supported socialization for people with psychiatric disabilities: lessons from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Community Psychology 32:453–477, 2004Google Scholar

6. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410–1421, 2000Google Scholar

7. Carlson LS, Rapp CA, McDiarmid D: Hiring consumer-providers: barriers and alternative solutions. Community Mental Health Journal 37:199–213, 2001Google Scholar

8. Cook JA, Jonikas JA, Razzano L: A randomized evaluation of consumer versus nonconsumer training of state mental health service providers. Community Mental Health Journal 31:229–238, 1995Google Scholar

9. Dixon L, Krauss N, Lehman A: Consumers as service providers: the promise and challenge. Community Mental Health Journal 30:615–625, 1994Google Scholar

10. Felton CJ, Stastny P, Shern DL, et al: Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatric Services 46:1037–1044, 1995Google Scholar

11. Fox L, Hilton D: Response to "Consumers as service providers: the promise and challenge." Community Mental Health Journal 30:627–629, 1994Google Scholar

12. Fisk D, Rowe M, Brooks R: Integrating consumer staff members into a homeless outreach project: critical issues and strategies. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 23:244–252, 2000Google Scholar

13. Goldstein MZ, Pataki A, Webb MT: Alcoholism among elderly persons. Psychiatric Services 47:941–943, 1996Google Scholar

14. Mowbray CT, Moxley DP, Collins ME: Consumer as mental health providers: first-person accounts of benefits and limitations. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:397–411, 1998Google Scholar

15. Paulson R, Herincks H, Demmler J: Comparing practice patterns of consumer and non-consumer mental health service providers. Community Mental Health Journal 35:251–269, 1999Google Scholar

16. Quinlivan R, Hough R, Crowell A: Service utilization and costs of care for severely mentally ill clients in an intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:365–371, 1995Google Scholar

17. Solomon P: Response to "Consumers as service providers: the promise and challenge." Community Mental Health Journal 30:631–634, 1994Google Scholar

18. Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney MA: The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:126–134, 1995Google Scholar

19. Solomon P, Draine J: Perspectives concerning consumers as case managers. Community Mental Health Journal 32:41–46, 1996Google Scholar

20. Solomon P, Draine J: Service delivery differences between consumer and nonconsumer case managers in mental health. Research on Social Work Practice 6:193–207, 1996Google Scholar

21. Edmunson ED, Bedell JR, Gordon RE: The Community Network Development Project: bridging the gap between professional aftercare and self-help, in Mental Health and the Self-Help Revolution. New York, Human Services Press, 1983Google Scholar

22. Clarke GN, Herinckx HA, Kinney RF, et al: Psychiatric hospitalizations, arrests, emergency room visits, and homelessness of clients with serious and persistent mental illness: findings from a randomized trial of two ACT programs vs usual care. Mental Health Services Research 2:155–164, 2000Google Scholar

23. Solomon P: Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:392–401, 2005Google Scholar

24. Simpson EL, House AO: Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. British Medical Journal 325:1265–1271, 2002Google Scholar

25. Rapp CA: The Strengths Model: Case Management With People Suffering From Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

26. Rapp CA: The active ingredients of effective case management: a research synthesis. Community Mental Health Journal 34:363–380, 1998Google Scholar

27. Marty D, Rapp CA, Carlson L: The experts speak: the critical ingredients of strengths model case management. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:214–221, 2001Google Scholar

28. Bedell JA, Lennox S: Handbook for Communication and Problem-Solving Skills Training: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Oxford, England, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

29. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Health Services Research 33:1285–1308, 1998Google Scholar

30. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201–215, 1998Google Scholar

31. Pattison EM: A theoretical-empirical base for social system therapy, in Current Perspectives in Cultural Psychiatry. Edited by Foulks EF, Wintrob RN, Westermyer J, et al. New York, Spectrum, 1977Google Scholar

32. Stein CH, Rappaport J, Seidman E: Assessing the social networks of people with psychiatric disability from multiple perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal 31:351–367, 1995Google Scholar

33. Dow MG, Ward JC: Assessment of consumer satisfaction: current practices and the development of the Behavioral Healthcare Rating of Satisfaction scale. Presented at the annual meeting of the National Conference on Mental Health Statistics, Center for Mental Health Services/Mental Health Statistics Improvement Project, Washington, DC, May 30–June 2, 1995Google Scholar

34. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–62, 1988Google Scholar

35. Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine 13:595–605, 1983Google Scholar

36. Walsh J: Social support resources outcomes for the clients of two assertive community treatment teams. Research on Social Work Practice 4:448–463, 1994Google Scholar

37. Walsh J: Social network changes over 20 months for clients receiving assertive case management services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:81–85, 1996Google Scholar

38. Chinman M, Young AS, Hassell J, et al: Toward the implementation of mental health consumer provider services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:176–195, 2006Google Scholar