Comparison of Public Attributions, Attitudes, and Stigma in Regard to Depression Among Children and Adults

The Surgeon General's 1999 report on mental health ( 1 ) contends that mental health problems of children and adolescents are less understood than those of adults. Childhood depression, in particular, provokes uncertainty and clinical controversy ( 2 ) and is among the least likely of all childhood mental health problems to receive treatment ( 3 ). Whereas parents seek treatment for children with disruptive disorders, youths with depression typically receive treatment only when they recognize need and ask adults for help ( 3 ). In light of these challenges, it is critical to understand public attitudes that may serve as additional barriers to care for children with depression and their families.

Recent research on adult depression continues to document the public's inability to recognize depression as a serious mental illness, an unwillingness to seek services, and the persistence of stigma ( 4 ). How the public assesses childhood depression remains an important gap in our knowledge. Because youths have little status and power in society, children with depression may be even more vulnerable than adults to stigmatization and punitive or coercive responses ( 5 ). In addition, stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness are fueled, in part, by media reports linking depression with youth violence, which lead to perceptions of dangerousness and instill fear ( 4 , 5 ). Using two nationally representative data sets that permit a direct comparison of attitudes toward adults and children with major depression, we offer a preliminary comparison of the public's recognition of depression as a mental health problem, attributions of the problem, associated stigma, and treatment recommendations.

Methods

Sample

Data came from two General Social Survey special modules on mental health problems among adults and children, given in 1996 and 2002 ( 4 , 6 ). Institutional review board approval for the General Social Survey was provided by the University of Chicago, and approval for secondary data analysis was given by Indiana University. Per standard protocol for in-person surveys, oral informed consent was secured at the time of the interviews. A randomly selected subset of respondents received a vignette in which an adult (in the 1996 module) or a child (in the 2002 module) met criteria for depression, followed by a series of questions about the character in the vignette. The vignettes were equivalent but not identical. Most notably, the vignette of the child mentioned suicidal ideation, whereas the vignette of the adult did not.

Respondents who received the adult vignette (N=193) and those who received the child vignette (N=312) ranged from 18 to 89 years old, with a mean age of 40.3±16.28 years in 1996 and 45.7±17.24 years in 2002. About 55% of the 1996 subsample and 63% of the 2002 subsample were women. African Americans composed 15% and 13% of the 1996 and 2002 subsamples, respectively. The main sample was self-weighting ( 7 ).

Variables

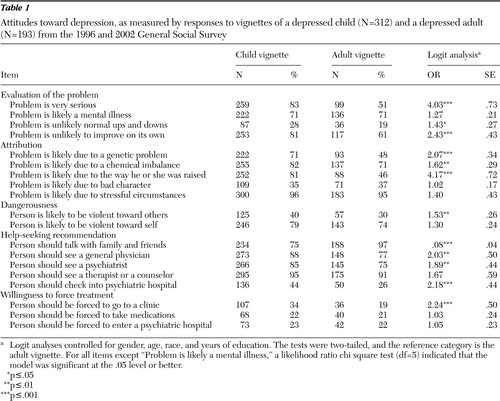

Five sets of binary variables were constructed and used in these analyses. All measured response to the depression vignette: evaluation of the problem, attributions, dangerousness, help-seeking recommendations, and willingness to coerce treatment. All variables were coded as 1 (such as very serious) or as 0 (otherwise) ( Table 1 ).

|

Analyses

Descriptive and bivariate logit analyses are reported. Odds ratios from each of the logistic regressions for the comparison of responses concerning children's and adults' depression (child, 1; adult, 0) on each variable are presented. On the basis of past research, all multivariate analyses controlled for gender, age, race, and years of education ( 4 ). Student's t tests are reported at the .05 level, and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

Table 1 indicates that more respondents believed that childhood depression is a very serious problem in comparison with adult depression, that it is not simply a response to the normal "ups and downs" of children's lives, and that it will not improve on its own. However, the respondents were equally likely to label adult and child depression as a mental illness.

Nearly all respondents attributed depression among adults and children to stress. However, more respondents attributed childhood depression to a genetic problem, a chemical imbalance, or the way the child was raised. Further, significantly more respondents believed that children with depression are more likely than adults with depression to be violent toward others. They were equally likely to see adults and children with depression as potentially dangerous to themselves.

Almost all respondents recommended that adults with depression talk to family and friends about their problem; however, only three-quarters of respondents recommended this strategy for children's caregivers. More respondents recommended almost all other sources of help for children with depression than they recommended for adults, including visiting physicians or psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitalization. Seeing therapists and counselors was the only exception, which respondents recommended for both age groups. Finally, more respondents were willing to force a child with depression to receive treatment from a mental health clinic or a physician.

On the basis of these findings, we ran additional analyses (controlling for gender, age, race, and years of schooling) to examine the potentially "contaminating" role of perceptions of dangerousness. These post-hoc analyses suggested that these perceptions drive most other public attitudes toward childhood depression (results available on request). Specifically, those who believed that children with depression are likely to be violent toward others were two to four times more likely to consider the problem serious rather than the normal ups and downs of life; to recommend seeking treatment from physicians, psychiatrists, and psychiatric hospitals; and to be willing to coerce a child with depression into treatment.

Discussion

Our analysis raises important concerns about the challenges facing families and providers confronting depression among children and adults. That almost half of respondents did not perceive depression among adults as a serious problem suggests a lack of "mental health literacy" about adult depression and its consequences. The findings for children, however, are both encouraging and discouraging. When respondents' attitudes toward adult and childhood depression were compared, more respondents viewed depression among children and adolescents as serious and in need of formal treatment. This finding may reflect the acceptance of contemporary psychiatric thinking about childhood depression; alternatively, as post-hoc analyses implied, it may signal an underlying fear and desire for threat reduction.

Overall, these results suggest that children with depression and their families may be more vulnerable than adults to stigmatization. Most problematic is the belief in children's greater potential for violence against others. Further, the greater willingness to mandate treatment for children is out of step with current psychiatric research and efforts of advocacy organizations. Finally, many people in the United States embrace popular representations of childhood depression as resulting from poor parenting—an attitude that stigmatizes families and creates barriers to care ( 5 , 8 ). This conclusion is only reinforced by the greater numbers of respondents unwilling to talk to friends and family about children's mental health problems compared with adults' problems.

Public knowledge and attitudes may rely on sensationalized media reports or direct-to-consumer advertising for information, as well as "commonsense" (but typically uninformed) inferences. In particular, the greater prevalence of beliefs that children with depression are likely to be violent toward others may reflect media attention to the role of mental disorders in the 1999 shootings at Columbine High School and other instances of youth violence. Despite research conclusions that "mental illness cannot be viewed as a straightforward predictor of a school shooting rampage" ( 9 ), many media accounts have emphasized mental health treatment that teen perpetrators had received and have quoted "experts" who have contended that there has been a "social epidemic" of violence among children and adolescents ( 10 ).

The inclusion of suicidal ideation in the child vignette might have skewed respondents' assessments. Ironically, however, this variation produced only a small, nonsignificant difference in evaluation of "danger to self" (less than 5% difference), whereas the difference for "danger to others" was double (more than 10% difference). Also, because data were collected six years apart, it is possible that findings reflect a broader trend toward increasing stigmatization of mental disorders rather than differing attitudes toward children and adults. Although this possibility seems unlikely to be true, given the relatively short period between waves, a design that planned a direct comparison within one survey would have been preferable.

This study represents only a first step in understanding the challenges that mental health providers and families face. Examining the full spectrum of mental health problems and the reasons underlying different responses to adult and child problems would offer additional guidance for treatment and for educational and antistigma campaigns.

Conclusions

Although adult mental disorders have long been misunderstood and stigmatized by the general public ( 4 , 8 ), childhood mental health problems have been shown here to receive a complicated public response. More recognition of the problem of depression and recommendations for help seeking were coupled with greater prejudice regarding some treatment and community responses. Stigma has been shown to have devastating effects on the psychological, emotional, and social development of children with mental disorders, significantly diminishing their life chances as adults ( 5 , 8 ). Without efforts to promote the understanding and acceptance of youths with mental disorders, stigma will continue to challenge children, families, and providers confronted by depression ( 5 ). Unless these efforts counter the public attitudes we document here that, for example, exaggerate violence, suggest secrecy among family members and friends, and affirm coercive societal response, stigma will continue to challenge children, families, and providers confronted by depression ( 5 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors acknowledge project support by the National Science Foundation to the National Opinion Research Center; Eli Lilly and Company; the Office of the Vice President for Research, Indiana University; and grant K02-MH-012989 from the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Pescosolido, principal investigator. The authors thank Tom Smith and staff members of the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research, Schuessler Institute for Social Research, Indiana University.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR: Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry 49:1002–1014, 2001Google Scholar

3. Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, et al: Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1081–1090, 1999Google Scholar

4. Martin JK, Pescosolido BA, Tuch SA: Of fear and loathing: the role of disturbing behavior, labels and causal attributions in shaping public attitudes toward persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:208–233, 2000Google Scholar

5. Hinshaw SP: The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46:714–734, 2004Google Scholar

6. Pescosolido BA: Culture, children, and mental health treatment: special section on the National Stigma Study-Children. Psychiatric Services 58:611–612, 2007Google Scholar

7. Davis JA, Smith TW, Marsden PV: General Social Survey 2002 [codebook file]. Princeton, NJ, Cultural Policy and the Arts National Data Archive, 2003Google Scholar

8. Hinshaw SP, Cicchetti D: Stigma and mental disorder: conceptions of illness, public attitudes, personal disclosure and social policy. Development and Psychopathology 12:555–598, 2000Google Scholar

9. Newman KS, Fox C, Roth W, et al: Rampage: The Social Roots of School Shootings. Cambridge, Mass, Basic Books, 2004Google Scholar

10. Garbarino J: Lost Boys: Why Our Sons Turn Violent and How We Can Save Them. New York, Free Press, 1999Google Scholar