Categorization of Aggressive Acts Committed by Chronically Assaultive State Hospital Patients

Assaultive behavior in psychiatric facilities has become a significant problem for mental health administrators ( 1 , 2 ). Each year nearly one in four public psychiatric nurses suffers a disabling injury from a patient assault, making it one of the most dangerous occupations for work-related injuries ( 3 , 4 ). Seclusion and restraints are frequently used to manage aggression ( 5 ), even though their use may present psychological and physical risks to patients ( 6 ). Unfortunately, our current understanding of the cause and optimal treatment of aggression remains limited ( 7 ). Clinicians treating repetitively violent patients have few pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions available to them, and there is uncertainty in knowing which interventions to use for which patients ( 8 ). Nonetheless, long-term psychiatric facilities strive to provide treatment designed to prevent inpatient assaults and minimize the risk that a patient will become violent when released to the community.

Recent research indicates that better understanding of the types of assaults occurring in psychiatric facilities can be useful in developing more specific interventions. A study at a state hospital in New York determined that an act of aggression can be classified on the basis of the factor motivating the assault ( 9 ). Fifty-five assaults were documented on videotape, and the assailant and victim were interviewed separately afterward in an attempt to identify the underlying cause for the aggression. This detailed analysis found that three primary motivations accounted for the aggression: disordered impulse control, an assault committed in response to an immediate provocation and associated with agitation and loss of emotional control; psychopathic motivation, a controlled, planned assault committed for a specific purpose or goal; and psychotic motivation, an assault committed by an individual acting under the influence of delusions, hallucinations, or disordered thinking. These findings are consistent with research that has identified two primary subtypes of human aggression—impulsive and premeditated ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 )—and a third form of aggression characterized as "medically related," which includes aggression committed by persons with psychiatric disorders ( 14 ).

In order to develop more rational and specific antiaggression treatments, it appears that characterizing aggressive behavior is important. Evidence is accumulating that indicates that specific types of aggression respond differently to medications ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ) and therapeutic modalities ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ). Consequently, efforts to reduce inpatient assaults should take into account the varying motivations for aggression, rather than view violent behavior homogeneously. Mental health administrators could implement treatment programs based on the type of aggression that predominates in a particular treatment setting. Individual clinicians could design more specific interventions in treatment plans designed to target the particular type of aggression being addressed.

In this retrospective study of chronically aggressive long-term psychiatric inpatients, we attempted to replicate the work of Nolan and colleagues ( 9 ) by using an alternative method of documenting assaults: a procedure for classifying assaults on the basis of a narrative description of the act ( 29 ). Although the use of record review is less rigorous and has other limitations, medical records are readily available to hospital personnel for clinical use. We attempted to further expand on previous work by using three steps. First, we developed a technique for subcategorizing assault types by identifying provocations leading to impulsive assaults, motives for organized assaults, and symptoms associated with psychotic assaults. Second, we determined the type of aggression that predominates in a state psychiatric hospital by reviewing multiple assaults committed by a large sample of randomly selected aggressive inpatients treated in various locations (civil and forensic) across the hospital. Finally, we characterized the victim (staff or patient) preferentially targeted by each type of assault.

Methods

Setting and population

This study was conducted at Napa State Hospital (NSH), a 1,190-bed long-term-care psychiatric facility located in Napa, California. Approximately 80% of the patients there are treated under a forensic commitment. These include persons acquitted by reason of insanity, those incompetent to stand trial, and offenders with a mental disorder. Offenders with a mental disorder are prisoners transferred to the hospital at the end of their prison term because a court has determined that their mental illness played a role in their crime and that they continue to present a substantial danger to the community if released on parole. The predominant instant (or committing) offense for these patients is a violent felony. The remaining 20% of patients are treated under civil commitments (mental health conservatorship). A majority of these patients were transferred to the hospital because of unmanageable aggression in a community facility. Eighty-five percent of patients at NSH are male, and the patients have a wide variety of primary psychiatric conditions, including psychotic disorders (80%), affective disorders (9%), cognitive disorders (5%), and personality disorders (3%). The average length of stay is more than three years, which permits longitudinal observation of patients. Treatment is provided on 26 different units, with an approximate census of 45 patients per unit. This study was approved by the University of California-Davis Human Research Protection Committee and the state's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, and a waiver of informed consent was granted.

Participants

Special incident reports. In order to identify the study sample, we utilized data obtained from special incident reports (SIRs). Special incidents are defined as any occurrence that is potentially or actually physically or psychologically harmful to a patient or has an adverse effect on the operation of the state hospital. Hospital staff are provided training in the documenting and reporting of special incidents as part of their orientation program to the hospital and receive additional training on a yearly basis. Staff witnessing or discovering an incident are responsible for making a detailed report describing the incident soon after it occurs. The report is then filed in the interdisciplinary notes section of the patient's chart. A copy of each SIR is sent to administration for the purpose of collecting and analyzing aggregate data, which is used for quality-improvement activities. The administration has maintained a SIR electronic database since November 1998. Information contained in the database regarding incidents involving patient aggression include the date and time of the assault, a general description of the nature of the act (for example, verbal or physical aggression), the victim of the assault (staff or patient), and whether the patient was the aggressor in the incident.

Chronically assaultive patients. Past research has shown that a small percentage of patients are responsible for a majority of assaults in institutional settings and are ten times more likely than other patients to inflict serious injuries ( 30 , 31 , 32 ). This study focused on these recidivistic assaulters, who were defined as patients committing at least three significant acts of aggression over a one-year period in the hospital. In order to identify patients meeting this criterion, we screened the SIR electronic database over a six-year period (from June 1998 to December 2004) and identified 298 patients who committed three or more physical assaults over the course of one year. In order to derive a random sample, data for each patient was then entered into Microsoft Excel and assigned a randomly generated number with the RAND function. This function returns an evenly distributed random number greater than or equal to 0 and less than 1. By using the sort function, the random numbers that were linked to the patients were sorted in ascending order to create a list of patients with corresponding research numbers. Patients were entered into the study sequentially until data on approximately 1,000 assaults were obtained.

Identification of assault motivation

Narrative description of assault. Using the SIR electronic database, we collected for further investigation the specific date and time that each of the study participants committed assaults. The corresponding narrative description was then located in the patient's medical record. The first step involved reviewing the description of the aggressive act as documented in the incident report. These reports are filed in the interdisciplinary notes, which are daily records of observations and treatment provided to patients by nursing staff. After reviewing the report, we checked interdisciplinary notes written in the days preceding and following the assault in order to gain additional information regarding the assault. We often found that a review of the events leading up to the assault, the clinical management of the incident, and the statements made by an assailant after the assault was very useful in providing the level of detail required to categorize an assault when the incident report was lacking in detail. It was not uncommon for assailants to disclose their reasons for an assault hours or even days after the incident.

Assault categorization. The narrative was used to categorize assaults as impulsive, organized, or psychotic by using a modified version of a procedure for classifying aggressive acts through the use of formal records. The procedure was originally developed by Stanford and Barratt ( 29 ) by using descriptions of assaults by prisoners contained in disciplinary reports. Impulsive assaults had the following characteristics: an identifiable, immediate provocation, agitated or out-of-control behavior (for example, pacing, anger, hostility, or yelling), verbal threats, failed attempts to calm the patient, lack of concern about consequences of the act or personal safety, no obvious secondary gain or long-term motive, or expressions of remorse after the incident. Organized assaults had the following characteristics: proactive or involved some degree of planning, unprovoked or minimal provocation, a social motive (for example, asserting dominance) or an external goal, use of a weapon, preceded by little warning or came as a surprise, an absence of agitation from the patient or an appearance of being in control of his or her behavior, or denial of the assault after the event. Psychotic assaults also were unprovoked; however, the attack lacked a rational alternative motive, and the assailant cited a symptom (delusion or hallucination) as the reason for committing the assault. In addition, evidence of psychosis was present before and after the assault.

If the information contained in the narrative description of the aggressive incident was not sufficient to classify a motivation for the assault, we attempted to gain further information by reviewing additional records (for example, treatment team conferences) and through behavioral consultations (for example, a psychological investigation into reasons for assaultive behavior and treatment recommendations). Assaults without a sufficient description to determine a motivation were coded "unable to determine."

Assault subcategorization. For all assaults categorized, we attempted to further subcategorize impulsive assaults by the provocation preceding the assault. We also organized assaults by the motive and organized psychotic assaults by the symptom driving the assault.

Provocations to impulsive assaults. Impulsive assaults occurred after an adverse interpersonal interaction with either a staff member or another patient. Seven subcategories were defined: directed, denied, restrained, rage, argument, disrespected, and bothered. Interactions with a staff member leading to assault of the staff member were broken down into the two subcategories: directed, a patient assaults the staff member after the staff member directs a patient to stop an unwanted behavior or start an activity, and denied, the patient assaults the staff member after the staff member refuses a patient's request. In addition, we created two other subcategories that involved interactions with a staff member leading to assault, but the victim was not the staff member who initially provoked the patient: restrained, a staff member is assaulted in the process of placing an agitated patient into seclusion or restraints; and rage, an agitated patient assaults a bystander patient who is in the vicinity but played no role in provoking the patient.

Impulsive assaults occurring after an adverse interpersonal interaction with another patient were broken down into three subcategories: argument, a patient assaults in the context of an argument that began verbally but escalated into physical violence with the assailant initiating the violence; disrespected, a patient assaults after the victim insults the assailant (for example, name calling) or makes statements that the assailant feels are disrespectful; and bothered, a patient assaults a victim whose behavior is perceived as bothering or irritating to the assailant (for example, following too closely, invading personal space, or talking or yelling incessantly).

Motives for organized assaults. Assaults with an organized motivation were subcategorized by the motive or goal for the aggressive behavior. Six subcategories were identified: retaliation, intimidation, extortion, cold threat, racial, and sexual. In the first subcategory, retaliation, a patient feels that he or she has been wronged and thus assaults in order to get even or exact revenge—for example, to settle a score. Second, with intimidation a patient assaults in order to assert his or her dominance over another individual, for example, bullying behavior. Third, with extortion a patient uses actual or threatened force in an attempt to obtain from another patient a desired item—for example, cigarettes, food, or money—to which the patient is not entitled. Fourth, with cold threat a patient implies that he or she will harm the victim at a future point if the victim does not comply with a request—for example, a patient calmly tells a nurse to "watch your back tomorrow" after a request for benzodiazepine is refused. Fifth, with racial motivation the patient assaults because the victim is a member of a particular ethnic group. And finally, with sexual motivation a patient behaves in a sexually aggressive manner toward another—for example, grabbing or making sexually inappropriate comments.

Symptoms motivating psychotic assaults. We identified five subcategories of assault motivated by psychotic symptoms: beliefs of harm, stealing, poisoning, talking or laughing, and commanding voices. These predominantly involved assaults in which the assailant acted under the influence of a paranoid idea or misinterpretation. With belief of harm as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim acting under the belief that the victim has harmed or is planning to physically harm the patient. With stealing as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim because he or she believes that the victim stole from him or her. With belief of poisoning as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim who is believed to be poisoning him or her—for example, via food or medications. With belief of talking or laughing as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim believed to be laughing at him or her or talking about him or her in a negative way. Another subcategory, belief of commanding voices, was used when a patient displaying signs of psychotic disorganization (disordered thought and speech or responding to internal stimuli) assaulted a victim without provocation and may have reported commanding auditory hallucinations to assault.

Some assault descriptions contained sufficient information to categorize a motivation, but there was not enough to subcategorize the assault. Alternatively, some assaults did not clearly fall into a particular subcategory. These assaults were coded as unspecified.

Data analysis

The primary author developed the procedure described above for categorizing and subcategorizing aggressive acts in a preliminary review of 400 assaults. On the basis of the review, a training manual was created that described the criteria for impulsive, organized, and psychotic assaults; specific subcategories for each type of assault along with examples of each; and situations in which an assault is unable to be categorized or subcategorized. This manual is available from the primary author. Before raters coded assaults independently, they were trained in the procedure. An interrater reliability was calculated for 93 assaults committed by eight patients, with the primary author as the standard. The kappa statistic was used secondary to the categorical nature of the data. Good consistency was obtained for each rater, both for coding the type of assault and the subcategory ( κ =.805 and .776, respectively, for rater 1 and .789 and .729, respectively, for rater 2). Chi square analyses were performed to determine the relationship between type of assault, whether the victim was a patient or staff, and legal status of the attacker (forensic or civil). All analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows, version 10.0.5.

Results

Chronically assaultive patients

Eighty-eight patients were identified as recidivistic assaulters. The sample was predominantly male (75 men, or 85%, compared with 13 women, or 15%). The mean±SD age of the sample was 41.4±10.6 years. The ethnic distribution of the sample was diverse, 38 patients were Caucasian (43%), 26 were African American (30%), 18 were Hispanic (20%), and six were Asian or of another ethnic origin (7%). As shown in Table 1 , most patients (57%) were in the hospital under a forensic commitment and 43% were being treated under a civil commitment statute. For the 50 forensic patients, the instant (or committing) offense was predominantly for a violent crime; 70% were charged with assault or battery. Most patients (75%) had a primary axis I chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 53% had axis II comorbidity ( Table 1 ).

|

Assault categorization

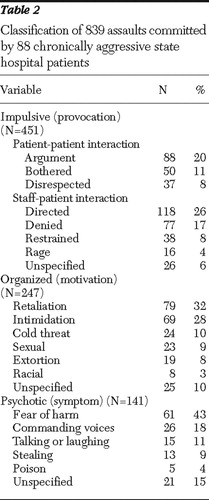

The 88 chronically aggressive patients committed a total of 983 assaults, representing a mean of 11.2±6.2 assaults per patient. The narrative description was insufficient to determine a category for 144 assaults (15%), so data for 839 assaults were analyzed ( Table 2 ). Impulsive assaults were most common (451 assaults, or 54%), followed by organized assaults (247 assaults, or 29%) and psychotic assaults (141 assaults, or 17%). There was a trend for organized assaults to be more likely to be committed by forensic patients (138 assaults by forensic patients, or 56%, compared with 109 assaults by nonforensic patients, or 44%), although this finding was not significant (p<.07). Additionally, although the overall number of assaults was fairly small for this group of forensic patients, when a patient who was incompetent to stand trial committed an assault, it was more likely to be classified as organized ( χ2 =25.6, df=8, p<.001).

|

Assault victim

Of the 839 total assaults for which a categorization was determined, patients were more likely to be the victim (506 assaults, or 60%) than staff (333 assaults, or 40%). However, as shown in Figure 1 , the type of assault victim was highly dependent on the type of assault ( χ2 =69.59, df=2, p<.001). Patients were more likely than staff to be targets of organized assaults (194 assaults, or 79%, compared with 53 assaults, or 21%) and psychotic assaults (100 assaults, or 71%, compared with 41 assaults, or 29%). Impulsive assaults were nearly equally likely to target staff and patients (239 assaults on staff, or 53%, compared with 212 assaults on patients, or 47%).

Assault subcategorization

As shown in Table 2 , the most common precipitants to an impulsive assault on staff occurred when an assailant was directed or asked to perform an activity by a staff member (26%) and when denied something he or she wanted by staff (17%); impulsive assaults on other patients most often occurred in the context of an argument (20%). The most common motive for organized assaults was retaliation or revenge for a perceived past wrong (32%). A vast majority of psychotic assaults were committed because the assailant falsely believed that the victim intended to harm him or her (43%). Other psychotic assaults were driven by similar paranoid delusional beliefs that the victim was talking about or laughing at the assailant (11%), stealing from the assailant (9%), or trying to poison the assailant (4%).

Discussion

In this sample of long-term inpatients with recidivistic aggression, the most frequent reason underlying assault was disordered impulse control. Staff members were most often victimized by impulsive assaults in situations that involved directing a patient to change unwanted behavior and refusal of a patient request. This finding is consistent with several past studies that have found that external provocations involving aversive interpersonal interactions to be the most common situation leading to assaults on staff—for example, setting restrictions on patients, ordering or demanding that a patient do something, and verbally denying a patient something that he or she wants or desires ( 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ). Further, psychiatric patients cite restrictions of their behavior, inflexible unit rules, misunderstanding of the rules, and poor communication with staff as the most common reasons for assaults on staff ( 37 , 38 , 39 ). These findings suggest that an effective prevention strategy for assaults on staff may be to ensure that patients have a clear understanding of unit rules and that the rules are consistently enforced.

This finding also underscores the important role that staff-patient interactions play in assaults on staff. Past research has indicated that the manner in which patients are approached by nursing staff is a significant factor in promoting assaults. Nursing staff with an authoritarian attitude, less experience, higher levels of anxiety, or a tendency to externalize blame are more prone to be assaulted ( 40 , 41 ). Thus staff training programs designed to develop clinical skills, such as deescalation strategies, in managing patients prone to impulsive aggression may be another effective method for addressing these assaults. Well-controlled studies have shown the effectiveness of behavioral therapies, such as the token economy approach, in reducing violence by chronic, institutionalized psychiatric patients ( 8 ). Patients who have chronic difficulties in controlling anger may respond to cognitive behavior strategies ( 25 ), and dialectical behavioral therapy has been shown to reduce violence among patients with borderline personality disorder ( 22 ).

Although impulsive motivations for assault were the most frequent in this sample, organized and psychotic assaults accounted for a substantial number of patient-to-patient assaults (294 of 506 assaults, or 58%). Past studies on reasons for inpatient aggression have not clearly described organized assaults, although a small number of assaults have been described as occurring without provocation or for no reason or as unexplained ( 33 , 42 , 43 ). The relatively large proportion of organized assaults may be related to the study site. Many of the past studies in this area were performed in acute, short-term, civil psychiatric facilities. A majority of patients in this sample were held under long-term forensic commitments, had a preexisting criminal history, and had long-standing antisocial characteristics—for example, 46 patients (53%) had axis II comorbidity, 26 of whom had antisocial personality disorder.

Organized, psychopathic, or premeditated aggression has been associated with antisocial or psychopathic personality disorder ( 44 , 45 ). Although this type of aggression is difficult to treat ( 23 , 27 , 46 ), it leads to extended patient commitment and should be addressed in an individualized treatment plan. There is some evidence that patients who commit acts of organized aggression may be effectively treated with cognitive-behavioral techniques that focus on altering pro-criminal beliefs and learning alternatives to aggression in resolving interpersonal conflicts ( 28 ). Treatment units that enforce a rigid set of rules and do not allow patients to make excuses for or rationalize behaviors to evade punishment may also be effective ( 26 ). As a last resort criminal prosecution could be considered for patients engaging in repetitive acts of planned, goal-oriented aggression ( 47 ). Because patients are involuntarily committed, they do not have the ability to escape from an aggressive inpatient. Thus removing assailants who victimize other patients may be ethically appropriate under Tarasoff reasoning, because it protects third parties and creates safer conditions of confinement.

Although most of the patients in the sample had a primary axis I psychotic disorder, assaults motivated by psychosis were the least common. The finding that most psychotic assaults were motivated by paranoid ideations is consistent with a number of studies that have associated acts of violence with persecutory delusions ( 48 , 49 ), "threat/control-override symptoms" ( 50 ), delusions of being poisoned ( 51 ), and suspiciousness ( 52 ). The relatively small number of psychotic assaults may be due to several factors. First, most patients are being held in the hospital under statutes that permit involuntary administration of antipsychotic medication; thus only those who are refractory or nonadherent to treatment are likely to experience active psychotic symptoms. Second, a number of decompensated psychotic patients in this sample appeared to commit predominantly impulsive assaults. Third, psychotic patients may not be repeatedly assaultive, and thus they are not included in the study sample. Clinical measures to prevent psychotic assaults could involve monitoring for signs of psychotic decompensation, routine checks to ensure compliance with antipsychotic medications, and the use of clozapine for treatment-refractory patients ( 18 ).

The primary limitation of this study was its retrospective design and reliance on medical records in order to determine motivations for assault. The amount and quality of documentation describing assaults varied considerably, and a number of assaults could not be categorized or subcategorized. This was particularly a problem for patient-to-patient assaults. Staff cannot observe patients continually, so many such assaults were not witnessed by a staff member. Consequently, in order to get details about these assaults, staff must conduct follow-up interviews with the assailant, victim, or both persons, both of whom may be unable or unwilling to provide information. If more information was obtained for the assaults with an undetermined motivation, we might have obtained a greater number of organized and psychotic assaults because these motivations are more common in patient-to-patient assaults. Further, when staff members describe assaults that they themselves were involved in, they may not be unbiased, objective reporters about their role in the assault episode.

Nonetheless, a significant amount of information was able to be obtained for a majority of assaults in this study. This method may have clinical utility for those who are treating patients with a history of repeated and persistent aggression. Past violent behavior is an important predictor of future violent acts ( 53 ). A detailed, systematic review of incidents of past aggression in formal records may provide useful data in characterizing a patient's aggressive behavior. An awareness of the motivations for past acts of aggression may assist psychiatric staff in recognizing the situations, provocations, and symptoms that indicate that a patient is at increased risk of assault. Early treatment intervention has the potential to prevent or minimize the severity of aggression and subsequent need for seclusion or restraints. For mental health providers treating patients in other settings, exploring and characterizing the motivation for aggressive behaviors may be useful in the formulation of violence risk assessments and can help guide treatment decisions.

Conclusions

Violence in long-term public psychiatric hospitals comes in many forms, each of which can be addressed with appropriate strategic interventions. These findings suggest that chronically aggressive patients should not be viewed as a homogeneous group. Interviewing assailants and documenting reasons for assault can be useful in revealing the underlying motivations for a patient's aggression. An accurate characterization of the type of aggression in which a patient engages may help clinicians in deciding on the interventions in an individualized treatment plan; at an institutional level, determining the types of aggression that predominate in a particular treatment setting can help mental health administrators implement specific programs in efforts to reduce the number of inpatient assaults.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the California Department of Mental Health, David Graziani, and Jeffrey Zwerin, D.O., for their support and encouragement of this research.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Flannery RB Jr, Hanson MA, Penk WE: Risk factors for psychiatric inpatient assaults on staff. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:24–31, 1994Google Scholar

2. Quintal SA: Violence against psychiatric nurses: an untreated epidemic? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 40:46–53, 2002Google Scholar

3. Carmel H, Hunter M: Staff injuries from inpatient violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:41–46, 1989Google Scholar

4. Love CC, Hunter ME: Violence in public sector psychiatric hospitals: benchmarking nursing staff injury rates. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 34:30–34, 1996Google Scholar

5. Kaltiala-Heino R, Tuohimaki C, Korkeila J, et al: Reasons for using seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 26:139–149, 2003Google Scholar

6. Fisher WA: Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1584–1591, 1994Google Scholar

7. Littrell KH, Littrell SH: Current understanding of violence and aggression: assessment and treatment. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 36:18–24, 1998Google Scholar

8. Harris GT, Rice ME: Risk appraisal and management of violent behavior. Psychiatric Services 48:1168–1176, 1997Google Scholar

9. Nolan KA, Czobor P, Roy BB, et al: Characteristics of assaultive behavior among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 54:1012–1016, 2003Google Scholar

10. Barratt ES: Measuring and predicting aggression within the context of a personality theory. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 3:S35–S39, 1991Google Scholar

11. Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Dowdy L, et al: Impulsive and premeditated aggression: a factor analysis of self-reported acts. Psychiatry Research 86:163–173, 1999Google Scholar

12. Weinshenker N, Siegel A: Bimodal classification of aggression: affective defense and predatory attack. Aggression and Violent Behavior 7:237–250, 2002Google Scholar

13. Stanford MS, Houston RJ, Mathias CW, et al: Characterizing aggressive behavior. Assessment 10:183–190, 2003Google Scholar

14. Barratt E, Kent T, Stanford M: The Role of Biological Variables in Defining and Measuring Personality. Cambridge, Mass, Blackwell Science, 1995Google Scholar

15. Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Felthous AR, et al: The effects of phenytoin on impulsive and premeditated aggression: a controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 17:341–349, 1997Google Scholar

16. Sheard MH, Marini JL, Bridges CI, et al: The effect of lithium on impulsive aggressive behavior in man. American Journal of Psychiatry 133:1409–1413, 1976Google Scholar

17. Stanford MS, Helfritz LE, Conklin SM, et al: A comparison of anticonvulsants in the treatment of impulsive aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:72–77, 2005Google Scholar

18. Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, et al: Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 24:225–228, 2004Google Scholar

19. Coccaro EF, Kavoussi RJ : Fluoxetine and impulsive aggressive behavior in personality-disordered subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1081–1088, 1997Google Scholar

20. Alpert JE, Spillmann MK: Psychotherapeutic approaches to aggressive and violent patients. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20:453–472, 1997Google Scholar

21. Andrews D, Bonta J, Hoge R: Classification for effective rehabilitation. Criminal Justice and Behavior 17:19–52, 1990Google Scholar

22. Evershed S, Tennant A, Boomer D, et al: Practice-based outcomes of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) targeting anger and violence, with male forensic patients: a pragmatic and non-contemporaneous comparison. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 13:198–213, 2003Google Scholar

23. Gabbard GO, Coyne L: Predictors of response of antisocial patients to hospital treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1181–1185, 1987Google Scholar

24. Goodness KR, Renfro NS: Changing a culture: a brief program analysis of a social learning program on a maximum-security forensic unit. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 20:495–506, 2002Google Scholar

25. Novaco R: Remediating anger and aggression with violent offenders. Legal and Criminological Psychology 2:77–88, 1997Google Scholar

26. Reid WH, Gacono C: Treatment of antisocial personality, psychopathy, and other characterologic antisocial syndromes. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 18:647–662, 2000Google Scholar

27. Rice M, Harris G, Cormier C: Evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and Human Behavior 16:399–412, 1992Google Scholar

28. Salekin RT: Psychopathy and therapeutic pessimism: clinical lore or clinical reality? Clinical Psychology Review 22:79–112, 2002Google Scholar

29. Stanford M, Barratt E: Procedures for the Classification of Aggressive/Violent Acts. New Orleans, University of New Orleans, 2001Google Scholar

30. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, et al: A prospective study of assaults on staff by psychiatric in-patients. Medicine, Science, and the Law 37:46–52, 1997Google Scholar

31. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al: Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1112–1115, 1990Google Scholar

32. Fotrell E: A study of violent behavior among patients in psychiatric hospitals. British Journal of Psychiatry 136:216–221, 1980Google Scholar

33. Conn L, Lion J: Assaults in a University Hospital. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1983Google Scholar

34. Powell G, Caan W, Crowe M: What events precede violent incidents in psychiatric hospitals? British Journal of Psychiatry 165:107–112, 1994Google Scholar

35. Sheridan M, Henrion R, Robinson L, et al: Precipitants of violence in a psychiatric inpatient setting. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:776–780, 1990Google Scholar

36. Whittington R, Wykes T: Aversive stimulation by staff and violence by psychiatric patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 35(part 1):11–20, 1996Google Scholar

37. Bensley L, Nelson N, Kaufman J, et al: Patient and staff views of factors influencing assaults on psychiatric hospital employees. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 16:433–446, 1995Google Scholar

38. Fagan-Pryor EC, Haber LC, Dunlap D, et al: Patients' views of causes of aggression by patients and effective interventions. Psychiatric Services 54:549–553, 2003Google Scholar

39. Ilkiw-Lavalle O, Grenyer BF: Differences between patient and staff perceptions of aggression in mental health units. Psychiatric Services 54:389–393, 2003Google Scholar

40. Johnson ME, Hauser PM: The practices of expert psychiatric nurses: accompanying the patient to a calmer personal space. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 22:651–668, 2001Google Scholar

41. Ray CL, Subich LM: Staff assaults and injuries in a psychiatric hospital as a function of three attitudinal variables. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 19:277–289, 1998Google Scholar

42. Crowner ML, Douyon R, Convit A, et al: Videotape recording of assaults on a state hospital inpatient ward. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 3:S9–S14, 1991Google Scholar

43. Harris G, Varney G: A ten-year study of assaults and assaulters on a maximum security psychiatric unit. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1:173–191, 1986Google Scholar

44. Williamson S, Hare R, Wong S: Violence: criminal psychopaths and their victims. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 19:454–462, 1987Google Scholar

45. Woodworth M, Porter S: In cold blood: characteristics of criminal homicides as a function of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 111:436–445, 2002Google Scholar

46. Kunz M, Yatesm K, Czobor P, et al: Course of patients with histories of aggression and crime after discharge from a cognitive-behavioral program. Psychiatric Services 55:654–659, 2004Google Scholar

47. Dinwiddie SH, Briska W: Prosecution of violent psychiatric inpatients: theoretical and practical issues. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 27:17–29, 2004Google Scholar

48. Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley K, et al: Violence in schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophrenia Research 26:181–190, 1997Google Scholar

49. Wessely S, Buchanan A, Reed A, et al: Acting on delusions. I: prevalence. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:69–76, 1993Google Scholar

50. Link BG, Stueve A, Phelan J: Psychotic symptoms and violent behaviors: probing the components of "threat/control-override" symptoms. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S55–S60, 1998Google Scholar

51. Mawson D: Delusions of poisoning. Medicine, Science, and the Law 25:279–287, 1985Google Scholar

52. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J: Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:566–572, 2000Google Scholar

53. Klassen D, O'Connor WA: Crime, inpatient admissions, and violence among male mental patients. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 11:305–312, 1988Google Scholar