The Role of Providers in Mental Health Services Offered to American-Indian Youths

American-Indian adolescents have high rates of addiction and mental health problems ( 1 ) but low rates of service use ( 2 ). The gap between service need and use appears to be even larger than the known gap for the general population ( 3 , 4 ), and few of the services are provided by specialists ( 5 , 6 ). This study examined the roles of providers in moderating the gap between need and services among American-Indian youths ( 7 ).

In general, whether youths are offered or referred to services strongly depends on an adult's awareness of problems and knowledge of service resources ( 7 ). When functioning in this role, these adults might be called "gateway" providers ( 8 ) because they open the gateway to services for youths. The providers may be professionals (mental health or addictions specialists or providers from primary health care, child welfare, juvenile justice, and education) ( 9 ) or informal providers (parents and respected elders) ( 10 , 11 ). In the American-Indian community, they might also be traditional providers (healers, medicine people, and ceremonial leaders) ( 5 , 12 , 13 ).

Regardless of the category of gateway provider, recognition of youths' service need is influenced by a number of factors. Gateway providers are more likely to identify a youth as needing services if the youth has functional impairments, comorbid conditions, and other risk factors ( 14 ). Similarly, they are more likely to recognize need if a youth has many problems or particularly visible problems ( 15 ). Training might improve identification because mental health professionals (for example, psychologists with doctorates and psychiatrists) identify a higher number of needy youths than other care professionals who help youths ( 16 ).

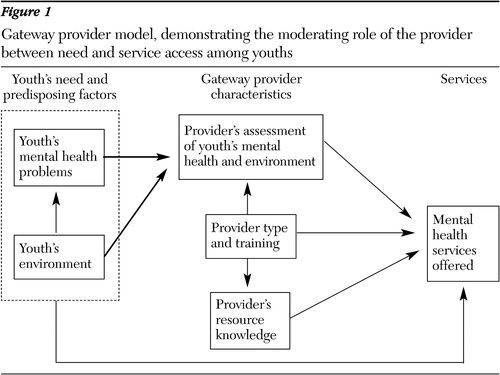

The gateway provider model was developed by Stiffman, Pescosolido, and Cabassa ( 7 ) in 2001 and is shown in Figure 1 . It adds to prior service models ( 17 , 18 ) by showing the moderating role of the provider between need and service access. On the basis of this model, we hypothesized that providers' assessment of youths' mental health and environment (determined by provider reports) and providers' resource knowledge (determined by provider training) predict services offered for American-Indian youths, as they do in other populations ( 19 ). To test this hypothesis, we used self-report data from youths and their providers that were collected during a study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The data included service use and drug use information for two American-Indian populations (urban and reservation) from a single southwestern state.

Methods

Sample

In 2001 a total of 401 youths (205 from a reservation and 196 from an urban area) aged 12 to 19 were interviewed for the American Indian Multisector Help Inquiry. The youths were randomly selected from complete tribal enrollment and school district records. Only one child per household was enrolled ( 5 ). The youths' mean±SD age was 15.5±1.5 years, and 176 (44 percent) were male.

Institutional review boards at Washington University, the tribal council, and the urban school district shaped consent and protection procedures ( 5 ). Personnel from local American-Indian educational and health services made the initial contact with the families. Only six families or youths refused in each area (12 total).

Youths who had received help in the prior year (2000) for mental health, addictions, or behavioral problems identified the individuals who helped them. The youths said they were served by 235 informal providers, 225 professional providers, and 47 traditional providers, but 46 of the youths who had a provider (about 20 percent) said that they did not know the provider's name. Within six months, 188 of those providers were interviewed.

Seventy of the providers interviewed were informal helpers (38 were parents or foster parents, 27 were other relatives, and five were from another group of informal helpers), seven were traditional healers, and 111 were professionals (96 nonspecialists and 15 specialists). Although the youths typically named multiple informal helpers, we sought to interview only each youth's primary informal helper and all professional (specialists and non-specialists) and traditional providers. Provider refusal rates were less than 5 percent.

We merged data on providers and youths to yield two data sets: one with 188 unique providers but repeated youths (more than one provider had served the same youth) and one with 141 unique provider-youth pairs. We present data only from the former in this article.

Interview procedures

In 2001 trained interviewers contacted the youths for whom guardian permission was granted and administered the interviews. The field supervisors and most interviewers were American Indian. Interviewers were required to accurately and smoothly complete a practice interview before entering the field. All interviews were audiotaped for monitoring and backup purposes. Supervisors, who gave immediate feedback, reviewed each interviewer's entire first two interviews and selected sections of further interviews.

Instruments

For structural equation modeling (SEM), manifest variables were used to create latent variables ( 20 ). Table 1 shows the alphas, means, and factor loadings of latent constructs in order to determine their validity in SEM and the gateway provider model.

|

a Factor loadings represent how well the measured variable represents the underlying latent construct.

Data on youths

Youths' report of mental health problems. A latent variable was created through factor analyses of symptom counts for questions concerning suicide, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, conduct disorder, violence, and substance (alcohol and other drugs) abuse or dependence. The questions came from the National Institute of Mental Health's Diagnostic Interview Schedule ( 21 ).

Identifying the gateway providers. The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents ( 22 ) was used to identify individuals who helped the youths. The modules were refined to conform to services available to American-Indian youths from the communities studied, including informal help and traditional American-Indian healing services.

Youths' perceived environment. A latent variable was created from seven manifest variables concerning neighborhood characteristics ( 23 ): drug dealing, shootings, murders, abandoned buildings, neighbors receiving welfare, homeless people on the street, and prostitution. Each question was scored with a 0, none; 1, some; or 2, a lot.

Data on providers

Provider surveys included two sections: a general-approach module with questions about providers' background and a youth-specific module with questions for providers about the specific youth and actions on behalf of the youth.

A latent variable indicating the providers' assessment of youths' mental health problems was calculated from two multi-item manifest variables: the providers' report of youths who presented with problems and the providers' rating (on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0, "no problem," to 4, "critical/meets diagnostic criteria") of the severity of each of six different types of mental health problems: depression or sadness, traumatic stress, anxiety, suicidality, alcohol misuse, drug misuse, and behavior or conduct disorder. This rating correlates with Achenbach's Teacher Report Form ( 24 ) at .68 and has a test-retest reliability of .86

A latent variable indicating the provider's assessment of the youth's environment was calculated from provider responses as to whether the youth had any of nine environmental problems: life stressors, family violence, problem peers, a violent neighborhood, violent school atmosphere, family instability, lack of family support, legal problems, or family financial problems. (The environmental aspects were not parallel to those asked of the youths.)

A latent variable for providers' resource knowledge was derived from ratings of 25 mental health resources. Knowledge of each resource was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 4. Each of the four possible points per mental health resource represented a unit of knowledge in the following categories: familiarity with available services, referrals to resources, referrals from resources, and contacts with available services ( 19 ). On average, providers were familiar with a mean±SD of 11.8±7.1 resources.

A latent variable for in-service training was operationalized from counts of topics covered in in-service training. The model was also tested for number of hours with no difference in significance. Thirty-four (36 percent) nonspecialist providers and 12 (87 percent) specialist providers received some type of in-service training in the past year. No traditional providers and only seven (10 percent) informal providers had any type of in-service training.

Provider type was a manifest ordinal variable that was based on employment and training rather than the provider's relation to the youth.

A latent variable for services offered was developed from questions about directly offering, recommending, or referring to the following ten possible addictions or mental health services: individual or group counseling, substance abuse treatment, involvement in a self-help group, crisis intervention, inpatient or residential mental health treatment, medication, psychiatric evaluation, family or marital counseling, service coordination or referral, or a discussion with the youth about the problem. The informal providers offered a mean of 1.6±.6 different services; traditional providers, 1.0±.5 different services; nonspecialists, 2.2±2.3 different services; and specialists, 4.8±3.7 different services. All youths who used specialist providers were referred to them by informal or nonspecialist providers ( 5 ).

Analyses

We used SAS software for all analyses ( 25 ). SEM was used to test how the youth's mental health and the provider's training were related to the provider's assessment of the youth's mental health and how the provider's assessment of the youth and how the provider's resource knowledge were related to services offered ( 26 , 27 ). The models were tested with weighted least-squares estimation in PROC CALIS ( 27 ) because of the ordinal nature of the variable indicating provider type ( 28 ). Paths with a beta of .10 or greater or with a significance level of .05 or less were retained in the model.

The analyses followed a two-step procedure ( 20 , 26 ). In step one, latent variables were created from iterated principal factor analysis. After oblique rotation items loading on the first factor were retained, the single factor analysis was rerun to obtain factor loadings. Factors used as indicator variables reduce the random error and uniqueness associated with indicators measured as straight summary scores ( 28 ). Step two was the SEM analysis, which used the latent variables in PROC CALIS to test the fit between our model and the data. Each data point was constituted by a unique provider (N=188). Analyses of the data set without any repeating youths (N=141) resulted in the same significant support for the hypothesis.

Results

As shown in Figure 2 , SEM revealed that variance in services offered (recommended, referred, or directly provided) was predicted largely by gateway providers' knowledge of youths' mental health problems and of service resources. (Provider type was not significant in the SEM that used only nonrepeating youths.) In all, 30 percent of the variance in providers' actions was predicted by providers' assessment of youths' addictions or mental health problems (.35), providers' resource knowledge (.24), and provider type (.19). In turn, 38 percent of the variance in providers' assessment of youths' addictions or mental health problems was predicted by youths' self-reported addictions or mental health problems (.33) and by providers' assessment of youths' environment (.46).

a Adjusted goodness of fit index=.93; χ 2 =19.91, df=14, p<.13; root mean square error adjusted=.05; 90 percent confidence interval=0-.095; ovals, latent variables; rectangles, manifest variables; curved arrows, covariance; straight arrows, direction of effects for correlations. Numbers along arrows represent standardized path coefficients. Numbers in ovals represent variance explained.

Thirty-three percent of the variance in providers' resource knowledge was predicted by in-service training (.42), provider type (.21), and youths' self-reported addictions or mental health problems (.16). Eighteen percent of the variance in in-service training was predicted by provider type (.43). Provider type correlated with youths' perceived environment (-.14, because youths with worse environments used more informal or traditional services than professional services) and with youths' self-reported mental health (.17, because youths with more problems used higher-level providers). As with other tests of the model ( 7 , 19 ), youths' report of their own addictions or mental health problems did not contribute directly to variance in services. The values of all the SEM indices for our model were high, with the adjusted goodness of fit index equaling .93. (Note: the model includes only 173 providers, as the CALIS procedure does listwise deletion when any variable is missing.)

Discussion

Our results support our hypothesis, based on the gateway provider, that the provider's assessment of a youth's mental health and environment (according to provider's reports) and the provider's resource knowledge (determined by the provider's training) predict services offered to American-Indian youths ( 7 , 19 ). The model explains 30 percent of variance in service receipt, an advance in variance explained over that of other service theories ( 17 , 18 ). As with other tests of the model, there is no direct path between service need and services offered ( 7 , 22 ).

Our findings suggest significant roles for gateway providers in the services offered to youths. However, other factors that may explain portions of the remaining variance include providers' beliefs and attitudes about services and mental health, which may be very culture specific. Also, American-Indian communities are concerned about both structural and perceptual service access and barriers. Unique aspects of these factors could have influenced the degree of service variance explained by the model.

Methodological issues might qualify the interpretation of our study. The study was confined to one reservation and one urban area, both from acculturated populations with relatively easy access to urban centers. Nevertheless, they were similar to many American-Indian groups because 39 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives were younger than 20, 60 percent lived in urban settings, and most belonged to similar midsize to small-size peri-urban reservations ( 29 ). Location (urban or reservation) was not significant in our model.

Another limitation concerns the cross-sectional nature of the data, which limits interpretations of causality. However, when a well-developed theory is used as a framework in SEM, the path coefficients may suggest (but not confirm) causation ( 30 ). A final limitation concerns the focus of this article on services and helpers without an explanation of what they actually did on behalf of the youths.

Despite any limitations, our study has important implications for interventions. Gateway providers (parents, professionals, and others) may be more likely both to identify a youth's problems and to refer a youth to services when they know community resources that are available to adolescents and know how to assess a youth's problems. It is possible that potential gateway providers are reluctant to even identify problems if they know of no resources to serve the problem. The model indicates the importance of disseminating knowledge about service resources.

Communities and agencies might better help parents, deputy juvenile officers, school counselors and teachers, health care professionals, and traditional providers to offer services by giving them information about assessing problems and extant service resources. Including parents and other informal providers in this information dissemination might enhance their use of professional helpers who offer even more services ( 31 ).

Our research should make parents, traditional healers, and other potential gateway providers acutely aware of the importance of their roles and actions in a youth's receipt of mental health services. Obviously, parents and traditional healers with more training offered, on average, more services; yet even those without specific mental health or addictions training could and did provide services.

Policy implications based on our results are relevant to administrators of agencies and organizations that serve all youths. The model indicates that one method for enhancing service receipt would be to find a way to enhance the natural helping network already available to youths. On a professional level, this would include nonspecialist providers and traditional healers, but parents are also important figures in this network. Policies to provide links between services to create seamless provision of services have long been recommended, with little effect when linkages are made administratively ( 32 ). Perhaps the most important linkages are to the gateway providers rather than at the administrative level.

Conclusions

Our results indicate two important avenues for potentially increasing services offered to youths. The first and most direct avenue involves increasing identification of problems by providers through training, screening, or emphasizing the importance of youths' mental health. The second avenue logically follows from our model. If knowledge of resources increases the offering of services, such knowledge should be widely disseminated to all individuals who have contact with youths.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant K02-MH01-797-01A1 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grants R24-DA-13572-0 and R01-DA-13227-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors give special thanks to Ed Brown, D.S.W., Edward L. Spitznagel, Jr., Ph.D., and Benjamin Alexander Eitzman, M.S.W.

1. Mental health care for American Indians and Alaskan Natives, in Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

2. Costello EJ, Farmer EMZ, Angold A, et al: Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: the Great Smoky Mountains study. American Journal of Public Health 87:827-832, 1997Google Scholar

3. Manson SM: Mental health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives: need, use, and barriers to effective care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 45:617-626, 2000Google Scholar

4. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al: Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs 14(3):147-159, 1995Google Scholar

5. Stiffman AR, Striley CW, Brown E, et al: American Indian youth: Southwestern urban and reservation youth's need for services and whom they turn to for help. Journal of Child and Family Studies 12:319-333, 2003Google Scholar

6. Novins DK, Beals J, Sack WH, et al: Unmet needs for substance abuse and mental health services among Northern Plains American Indian adolescents. Psychiatric Services 51:1045-1047, 2000Google Scholar

7. Stiffman AR, Pescosolido B, Cabassa L: Building a model to understand youth service access: the Gateway Provider Model. Mental Health Services Research 6:189-198, 2004Google Scholar

8. Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Leventhal JM, et al: Identification and management of psychosocial and developmental problems in community-based, primary care pediatric practices. Pediatrics 89:480-485, 1992Google Scholar

9. Mechanic D, Angel R, Davies L: Risk and selection processes between the general and the specialty mental health sectors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32:49-64, 1991Google Scholar

10. Alegria M, Rogles R, Freeman DH, et al: Patterns of mental health utilization among island Puerto Rican poor. American Journal of Public Health 81:875-879, 1991Google Scholar

11. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RI, et al: Factors affecting the probability of youth of general and medical health and social/community services for Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Medical Care 26:441-452, 1988Google Scholar

12. Kim C, Kwok YS: Navajo use of native healers. Archives of Internal Medicine 158:2245-2249, 1998Google Scholar

13. Beals J, Manson S, Whitesell NR, et al: Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:99-108, 2005Google Scholar

14. Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Angold A, et al: How can epidemiology improve mental health services for children and adolescents? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:1106-1115, 1993Google Scholar

15. Semlitz I, Gold MS: Diagnosis and treatment of adolescent substance abuse. Psychiatric Medicine 3:321-335, 1987Google Scholar

16. Summers DA, Faucher T, Chapman SB: A note on nonprofessional judgments of mental health. Community Mental Health 9:169-177, 1973Google Scholar

17. Mechanic D: Correlates of physician utilization: why do major multivariate studies of physician utilization find trivial psychosocial and organizational effects? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 20:387-396, 1979Google Scholar

18. Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, et al: Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Services Research 33:571-596, 1998Google Scholar

19. Stiffman AR, Hadley-Ives E, Elze D, et al: Impact of environment on adolescents' mental health and behavior: structural equation modeling. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 69:73-86, 1999Google Scholar

20. Hatcher L: A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1994Google Scholar

21. Robins LN, Helzer JE: The half-life of a structured interview: the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatry Research 4:95-102, 1994Google Scholar

22. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): a review of reliability, validity, adult-child correspondence, and versions, in Outcomes for Children and Youth With Behavioral and Emotional Disorders and Their Families: Programs and Evaluation Best Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Epstein M, Kutash K, Duchnowski A. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, 2005Google Scholar

23. Stiffman AR, Hadley-Ives E, Dore P, et al: Youth's access to mental health services: the role of providers' training, resource connectivity, and assessment of need. Mental Health Services Research 2:141-154, 2000Google Scholar

24. Achenbach TM: Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Edited by Maruish ME. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1994Google Scholar

25. SAS Procedures Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

26. Hoyle RH (ed): Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

27. SAS Online Doc, version 8. SAS Institute, Inc. Available at http://v8doc.sas.com/sashtml. Accessed Sept 26, 2005Google Scholar

28. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH: Psychometric Theory. New York, McGraw Hill, 1978Google Scholar

29. Overview of race and Hispanic origin. Census 2000 brief no C2KBR/01-1. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2001Google Scholar

30. Pedhazur EJ, Schmelkin LP: Measurement, Design, and Analysis: An Integrated Approach. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1991Google Scholar

31. Costello EJ, Pescosolido BA, Angold A, et al: A family network-based model of access to child mental health services. Research in Community and Mental Health: Social Networks and Mental Illness 9:165-190, 1998Google Scholar

32. Bickman L: Resolving issues raised by the Fort Bragg evaluation: new directions for mental health services research. American Psychologist 5:562-565, 1997Google Scholar