Discharge Against Medical Advice From Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment: A Literature Review

The nature of today's discharge against medical advice from psychiatric hospitalization has been progressively shaped by clinical, social, and legal advances in the mental health system over the past 50 years ( 1 ). Before the advent of the early psychotropic medications in the late 1950s and the mass exodus from state hospitals that followed, a patient was considered discharged against medical advice if he or she managed to escape from the hospital and did not return within an allotted period. The definition of discharge against medical advice was altered dramatically as the legislative changes of the ensuing decades afforded patients greater control over the course of their treatment, including the ability to sign out of the hospital against medical advice ( 2 , 3 ). The nature of discharge against medical advice was further shaped by the strong anti-establishment, humanistic social currents of the 1960s and 1970s, such as the community support system movement, which was a concerted public outcry that condemned the stigmatizing and punitive aspects of long-term psychiatric hospitalization and emphasized hope, empowerment, positive expectations, and community collaboration ( 4 ). The collective impact of the changes over the past half-century was to reduce the inpatient census by an astounding 92 percent and shift inpatient psychiatric treatment away from its traditional parens patriae role to short-term stabilization and acute care, engendering a new "revolving door" population characterized by frequent, brief hospitalizations and discharges against medical advice ( 5 ). Psychiatric discharge against medical advice, albeit a natural consequence of the relative increase in treatment options and patients' autonomy in making decisions about their care, has been associated with detrimental health outcomes and is a source of frustration to the mental health professionals who care for these patients ( 5 , 6 , 7 ).

Few attempts have been made to integrate factors surrounding discharge against medical advice despite a quite substantial body of literature on the topic. Jeffer ( 7 ) reviewed findings from various settings and patient populations and reported prevalence rates of discharge against medical advice ranging from .7 percent at a university general hospital to 51 percent at a child psychiatric outpatient clinic. The most common predictors were substance abuse, male gender, younger age, and lower socioeconomic status. The only significant outcome was higher readmission rate for patients discharged against medical advice. Reasons for leaving were dissatisfaction with care; personal, family, and financial reasons; and subjective improvement in symptoms ( 7 ). Baekeland and Lundwall ( 6 ) reviewed studies of dropout from various psychiatric settings and outlined several variables associated with discontinuing care: younger age; male sex; lower socioeconomic status; social isolation; social instability; symptom levels and lack of symptom relief; aggressive and passive-aggressive behavior; psychopathic tendencies; poor motivation; poor psychological mindedness; detrimental therapist attitudes and behavior; and family pathology, attitudes, and behavior. Prevalence among voluntary psychiatric inpatients ranged from 32 to 79 percent ( 6 ).

Past reviews have several important shortcomings. First, there has been a lack of unified standard of what constitutes a discharge against medical advice. Second, there has been a lack of focus with regard to treatment settings from which study samples were drawn, resulting in improper aggregation of findings. Third, change in prevalence rates over time has not been addressed. Finally, consequences of discharge against medical advice have not received sufficient attention.

We designed this study to provide an updated review of the literature on the topic and ameliorate the shortcomings of the prior reviews. We focused our review on studies of discharge against medical advice from inpatient psychiatric settings and concentrated on six key areas: definitions (what constitutes a discharge against medical advice); prevalence (the prevalence of discharge against medical advice and how it has changed over the past 50 years); predictors (who these patients are and why they leave); temporal factors (when these patients leave); outcomes (what happens to these patients after they leave); and interventions (what has been done to prevent patients from leaving against medical advice).

Methods

We searched the PubMed and PsycINFO databases (1955-2005) using a list of terms, keywords, and subject headings generated from PubMed's Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and PsycINFO's Thesaurus and Rotated Index tools. Search results were limited to English-language publications. On the basis of term lists that were generated, we searched the PubMed database for "patient discharge," "treatment/patient dropout," "against medical advice," "psychiatry," "psychiatric hospital," and "mental disorders," and we also searched the PsycINFO database for "against medical advice," "treatment dropouts," "hospital discharge," and "patient discharge." References resulting from the database search were downloaded into a bibliographic manager program, and titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance. To be included in this review, a study had to be done in an inpatient psychiatric setting (excluding substance abuse and day treatment facilities); at least one aspect of the study's aims, methods, or results had to include discharge against medical advice (excluding escape); and the study methodology had to include a comparison group or rely on formal data analyses. We obtained all articles meeting these criteria and reviewed reference sections for any publications that may have been missed during the original literature search. The resulting compilation of articles made up our study sample and was subsequently studied and analyzed.

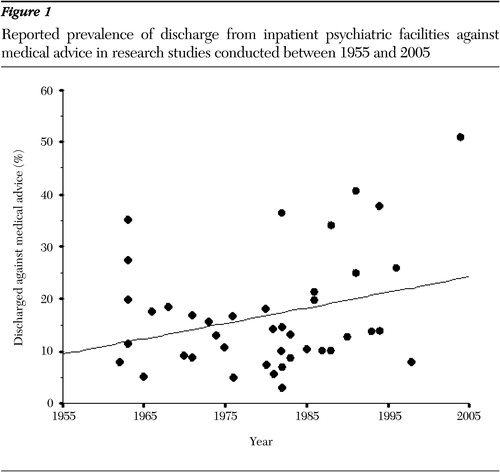

We harvested the following variables from the articles: year and type of publication; study aims; data collection methods; clinical setting and population that made up the study sample; mode by which the patients left the hospital; statistically significant predictor, outcome, and temporal variables; reported reasons for leaving; and operational definitions used by the studies to classify patients as discharged against medical advice. We also recorded percentage of prevalence of patients discharged against medical advice from studies reporting such figures and calculated prevalence for studies that did not explicitly state it but had sufficient data to make a calculation without making any inferences about the original data. In our prevalence calculations we used the formula most commonly used by past studies (prevalence= N DAMA /N PR ×100), where N DAMA is the number of patients discharged against medical advice and N PR is the number of patients at risk of being discharged in that manner. We averaged the prevalence for studies that reported more than one estimate, for example, for different hospitals or units. We then completed descriptive statistics on all variables and used nonlinear regression and curve-fit modeling techniques with the SPSS version 11.5 statistical software package to assess change in prevalence over time.

Results

Sixty-one articles met the inclusion criteria for this review. Fifty-six studies reported on predictors, 14 reported on temporal factors, 14 reported on outcomes, and one study reported on interventions for discharge against medical advice. Forty-three studies in our sample reported prevalence figures or contained sufficient data for a calculation to be made. Fifty-four studies collected data via retrospective review of the records, 17 used interviews with patients or staff, and six conducted follow-up via telephone or mail. Several studies used a combination of these methodologies, thus the excess in the total number of studies. Our search did not reveal any articles published between 1955 and 1960; ten studies were published in the 1960s, 12 in the 1970s, 24 in the 1980s, 13 in the 1990s and two thus far in the current decade. Of interest, the 1980s' peak in the number of studies appears to coincide with the upsurge in patients' rights litigation in that decade.

Definitions

Discharge against medical advice has been defined, in the broadest terms, as any patient who "insists upon leaving against the expressed advice of the treating psychiatrist" ( 8 ), but the actual operational criteria for labeling patients as discharged against medical advice varied widely across studies. Examples of such criteria are that the patient was marked as discharged against medical advice in the medical record, the patient left sooner than a preestablished length of stay, and discharge was defined as against medical advice on the basis of the subjective opinion of the treatment staff.

Studies also used type of treatment setting (voluntary or involuntary) and mode through which the patient left the hospital to define discharges as having occurred against medical advice. We identified two such situations from the literature. Namely, patients can "sign out" from voluntary treatment settings despite the psychiatrist's recommendation, generally after being briefed about the risks and signing a form accepting responsibility. Alternatively, patients can be "decertified" or released from involuntary hospitalization after insufficient cause for continued involuntary stay is determined in a court proceeding or a less formal legal hearing. Escape (absence without leave, absconding, or elopement), whereby the patient leaves the hospital without notification by escaping from an involuntary unit or walking out of a voluntary unit, also has been considered by some clinicians and researchers to be a form of discharge against medical advice. Others, including the authors of this review, do not regard escape as a form of discharge against medical advice because the essential element of psychiatrist's expressed advice against leaving is lacking in this situation.

In our review, 16 studies examined sign-outs from voluntary units, one study concentrated on decertified patients, and most (44 studies) either applied a combination of discharge modes or did not describe how the patients in their sample were discharged.

Prevalence

Forty-three studies in our sample reported prevalence figures or contained sufficient data for a calculation to be made. Prevalence of discharges against medical advice in our sample ranged from 3 to 51 percent, with a mean of 17 percent. The mean prevalence figure, however, has limited ecological meaningfulness, because it has been aggregated from literature going back to the inception of the deinstitutionalization movement. Social, legal, and institutional factors that underlie the issue have undergone dramatic fluctuations over the past five decades, and therefore so have prevalence rates. As such, the mean rate is not a meaningful estimate of current prevalence of discharge against medical advice. To avoid the inherent limitations of the aggregated mean rate, we used the regression method to estimate change in prevalence over time. Visual analysis and curve fitting suggested that prevalence data as a function of study year was best defined by the nonlinear, quadratic model. We used this model to fit a regression line to the prevalence data, which showed an increasing trend over time ( Figure 1 ). We then used the quadratic model to generate a regression equation that was useful in estimating a prevalence rate for any given year. This equation (y′=0366199x 2 -144.7412909x+143,035.6678374) is a simple quadratic formula, in which the coefficients are based on the prevalence data harvested from the studies in our review. Prevalence may be estimated by substituting the year of interest for the x variable. For example, estimated prevalence rate for the year 2000 would be (.0366199) (2000 2 )-(144.7412909)(2000)+143,035.6678374 =32.7 percent.

Predictors

Fifty-six studies in our review reported significant predictors of discharge against medical advice. The predictors fell into two broad categories: patient variables—sociodemographic characteristics, diagnosis, treatment history, behavior, and attitudes toward treatment—and provider variables—hospital setting and structure, staffing patterns, admission and discharge policies, and psychiatrists' clinical style and experience.

Patient variables

Studies that found sociodemographic factors to be predictive of discharge against medical advice noted that these patients were significantly younger than individuals in a control group or the overall hospital population ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). Findings regarding gender were mixed, with studies reporting both male gender ( 12 , 15 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ) and female gender ( 24 , 25 , 26 ) as being predictive. Findings regarding marital status were also mixed, with studies citing both unmarried ( 12 , 15 , 16 , 19 , 23 , 27 ) and married ( 12 , 24 , 26 , 28 ) status as predictive of discharge against medical advice. Similarly, studies that found socioeconomic predictors to be significant implicated both lower ( 19 , 29 , 30 ) and higher ( 8 , 13 ) socioeconomic status. One study found other-than-Caucasian ethnicity to be predictive ( 23 ).

Studies examining diagnostic factors found that the presence of comorbid substance use disorder increased the likelihood of discharge against medical advice ( 12 , 16 , 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). Other axis I diagnoses predictive of discharge against medical advice included psychotic ( 15 , 16 ) and depressive ( 24 ) disorders. Discharge against medical advice was also linked to general axis II psychopathology ( 8 , 10 , 13 , 15 , 21 , 34 ), specifically to antisocial ( 11 , 35 ), borderline ( 36 ), paranoid ( 37 ), and schizoid ( 37 ) personality disorders. Patients who left against medical advice were also found to have greater severity ( 16 , 34 ) and length ( 12 ) of illness at the time of admission. A study of inpatients at a specialized anorexia nervosa clinic found that patients with the purging type of binge eating disorder were more likely to terminate treatment than those with the restricting type of the disorder ( 38 ).

Studies that examined prior treatment history of patients discharged against medical advice reported greater number of prior hospitalizations ( 23 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 39 , 40 ), prior history of discharges against medical advice ( 33 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ), and prior history of appearances before a legal hearing ( 29 ) to be predictive of discharge against medical advice.

Studies examining the type and context of the index admission found that patients discharged against medical advice were more likely to have been admitted through crisis ( 15 , 37 , 45 ), involuntarily ( 44 ), or under pressure from family or courts ( 8 ). On the contrary, other studies linked voluntary self-admission without pressure to discharge against medical advice ( 10 , 32 ). Studies also noted that patients who were admitted during weekend shifts ( 10 , 32 , 42 ), when staffing and staffing continuity are reduced, had an increased likelihood of being discharged against medical advice.

Studies examining inpatient treatment regimen reported that patients who were not taking any medication ( 29 , 46 ) or who were not taking enough medication ( 29 ), who received no counseling ( 33 ), or who received less attention from treatment staff ( 47 ) tended to be at greater risk of leaving against medical advice.

Behavioral factors that distinguished patients discharged against medical advice were antisocial, aggressive, or disruptive behavior ( 12 , 31 , 33 , 39 , 48 ); suicide attempts ( 13 , 49 ); poor hygiene ( 12 ); and medication noncompliance ( 44 ).

Studies examining attitudes toward hospitalization and reasons for leaving reported that patients who were discharged against medical advice expressed pessimistic attitudes toward treatment upon admission ( 8 , 12 , 33 , 43 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 ). When their reasons for leaving were directly solicited, patients reported dissatisfaction with treatment ( 13 , 15 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 42 , 53 ), pressure from or responsibility to family ( 21 , 42 , 53 ), and desire to obtain prohibited substances ( 34 ).

Provider variables

Studies noted that factors predictive of discharge against medical advice are not unique to patients. Among variables attributable to providers, studies cited failure to orient the inpatient to treatment on intake ( 35 , 37 , 47 ), a punitive or threatening atmosphere on the inpatient unit ( 37 , 44 ), difficulties in doctor-patient relationship ( 14 , 35 , 37 , 47 , 54 ), and inadequate unit staffing patterns ( 43 ). An interesting finding based on staff ratings of therapeutic effectiveness at four separate inpatient units was that older patients (37-60 years) left mostly from a poorly rated unit whereas younger patients (18-27 years) left mostly from a favorably rated unit ( 55 ). Another study reported that staff apparel (street dress compared with white uniforms or mixed dress) did not significantly affect the type of discharge from a psychiatric unit of a community general hospital ( 56 ).

Studies also noted that rates of discharge against medical advice tended to vary among individual clinicians ( 11 , 14 , 40 ). Specifically, female therapists ( 25 ) and psychiatric residents ( 35 ) had more patients who discharged themselves against medical advice than their male or attending colleagues. Reasons underlying differential rates of such discharge have not been thoroughly explored. One study reported that psychiatrists whose patients had the highest rates of discharge against medical advice did not differ on supervisors' ratings or therapeutic effectiveness from those with the lowest rates ( 57 ).

Temporal factors

Fourteen studies in our review attempted to ascertain when, rather than why, patients tend to leave against medical advice. Although the actual length of stay varied with treatment settings, studies noted that discharges against medical advice tended to occur within the initial critical therapeutic period when treatments were being initiated ( 9 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 31 , 37 ). Several studies reported increased incidence of discharge against medical advice during evening or night shifts ( 10 , 15 , 32 , 40 , 42 ) and during spring or summer months ( 9 , 29 ).

Outcomes

Fourteen studies in our review described the consequences of discharge against medical advice. Namely, patients discharged in this manner showed reduced benefit from treatment ( 8 , 23 , 58 , 59 ); fared worse in the outpatient sector on indices of psychiatric ( 58 ), medical ( 8 , 60 , 61 ), psychosocial ( 8 , 58 ), and socioeconomic ( 58 , 60 ) functioning; overused emergency care and underused outpatient services ( 62 ); and were re-hospitalized sooner ( 29 ) and more frequently ( 23 , 29 , 32 , 58 , 62 , 63 ).

Interventions

The only study in our sample to examine a possible intervention described a 32 percent drop in discharge against medical advice from a large private general psychiatric hospital after the implementation of a new patient advocate staff position that was designed to orient new patients to the hospital and act as a staff-patient intermediary ( 64 ).

Discussion

The nature of psychiatric discharge against medical advice has been defined by the same legal and societal pressures that have redefined the nature of the larger mental health system over the past 50 years. Although the legal decisions resulted in a less restrictive mental health system, the humanistic social movements, such as the community support system movement, empowered patients with psychiatric illness to take an active role in the course of their treatment, and government policy (at least in theory) made outpatient and community services available. As such, today's patients who leave inpatient facilities against medical advice embody both the achievements and failures of today's inpatient psychiatry in that they face a system that affords them every right to terminate treatment but provides limited options once they have stepped outside the hospital door ( 65 ).

This review suggests that patient, treatment, and temporal factors predict discharge against medical advice. Namely, patients who are at greater risk of being discharged against medical advice tend to be young, single men with comorbid diagnoses of personality or substance use disorders and who have pessimistic attitudes toward treatment; often engage in antisocial, aggressive, or disruptive behavior; and have a history of numerous hospitalizations ending in discharges against medical advice.

Studies also showed that patients tended to leave from units that did not orient them to inpatient treatment and failed to establish a supportive provider-patient relationship. Proper orientation during the early treatment phase is essential to keeping the patient in the hospital, as indicated by the findings that patients discharged against medical advice tended to be admitted on weekends and discharged during evening and night shifts when unit staffing is at its lowest and tended to leave during the initial part of hospitalization. The study that reported a dramatic decrease in the rate of discharge against medical advice after implementation of a patient advocacy position further supports the importance of the provider-patient relationship.

Outpatient careers of patients discharged against medical advice are characterized by relatively poor outcomes in several domains of functioning, as well as by frequent rehospitalizations. This trend, along with the relatively high prevalence of unadvised discharge, suggests that these patients make a sizable contribution to the growth of today's revolving-door population of psychiatric patients.

Our findings regarding the predictors and outcomes of discharge against medical advice are generally consistent with those of the earlier literature reviews, with the exception of lower socioeconomic status, which was reported by both Jeffer ( 7 ) and Baekeland and Lundwall ( 6 ) to be predictive of discharge against medical advice. No clear pattern with regard to socioeconomic variables emerged from our review.

A collective look at the studies in our review offers an insight into the cyclical dynamic underlying discharges against medical advice. Studies point out that patients who were later discharged against medical advice tended to regard hospitalization as punitive on intake, which diminished their motivation for treatment. They were often dissatisfied with their treatment regimen, felt unprepared for the hospitalization experience, expressed negative attitudes about psychiatric treatment in general, and were pessimistic about their clinical outcomes. In turn, such attitudes tended to alienate the treatment staff, undermining the effectiveness of treatment delivery and amount of therapeutic contact, and eventually precipitating a vicious cycle marked by premature discharges and brief, frequent rehospitalizations.

Limitations

Several limitations in our review necessitate discussion. Although our electronic database search was designed to be thoroughly inclusive, we may have missed some pertinent articles.

Our review did not include studies that looked exclusively at patients who escaped from the hospital. Although some researchers have considered such patients discharged against medical advice, we felt that they were outside the scope of this review, which concentrated on discharge against the expressed advice of the treatment team, an element not present when a patient decides to escape or otherwise leave without informing the staff. The literature pertaining to escape from psychiatric treatment was reviewed in detail elsewhere ( 66 , 67 ). We realize, however, that studies that combined or did not identify the mode of discharge might have included escaped patients and that these patients might have biased our analyses.

Although a meta-analysis would have been a stronger method for this review, the level of methodology in the original studies would not permit a formal meta-analysis to be conducted. Studies in our review analyzed different sets of potential predictor and outcome variables, making standardized aggregation of statistically significant results problematic. Furthermore, most studies did not contain any standard effect measures that could fit any single meta-analytic effects model.

Our conclusions are further limited by the methodology of the studies in our review. Statistical procedures in several studies relied on univariate analyses, comparing regularly and irregularly discharged patients on a number of potentially predictive variables. This method, while effective in determining significant differences between groups of patients, may not be appropriate for prediction of a clinical outcome, such as discharge against medical advice.

A note of caution also is needed with regard to our prevalence calculations. Given that a regression equation is nothing more than a line representing the best-fit trend for all points in a data set, the coefficients in our regression equation are solely derived from the 43 prevalence data points in our review. Future studies reporting prevalence will have to be factored into the regression, which will change the associated coefficients. As such, the equation outlined in the Results section should not be used to predict future trends in the prevalence of discharge against medical advice.

Guidelines for clinicians

Research on factors associated with discharge against medical advice is only as good as the practical clinical solutions it promotes, yet attempts at devising measures capable of identifying patients at greater risk for discharge against medical advice have not met with considerable success ( 52 ). Although each treatment setting presents a unique set of circumstances, several universal trends emerged from our review that may be useful in identifying patients' potential for unadvised discharge and in keeping the high-risk patients in treatment.

Young, male patients with a dual diagnosis who have histories of disruptive or noncompliant behavior and frequent hospitalizations ending in discharges against medical advice should receive closer attention at intake. Steps should be taken, specifically during early stages of hospitalization, to forge a supportive patient-provider relationship, orient these patients to treatment, educate them on the benefits of hospitalization, and address the secondary diagnosis. If a patient still expresses the wish to exercise his or her right to terminate treatment, a formal debriefing should be arranged with a member of the treatment team. The clinician should solicit the patient's reasons for leaving, inform the patient about the consequences of his or her decision, and ask the patient to sign a formal discharge against medical advice form that summarizes the content of the discussion. The form can then be used in the subsequent hospitalization to devise a treatment plan that takes the patient's concerns into consideration.

Directions for future research

Prevalence of discharge against medical advice appears to be on the rise, yet the number of studies published on the topic shows a downward trend beginning in the 1980s. Clearly, more research is needed to further elucidate the factors involved in discharge against medical advice. We have identified several weaknesses in prior research that could be ameliorated in future studies. For example, researchers should clearly define the criteria used to label discharges as being "against medical advice," including a description of the study population in terms of treatment setting characteristics and modes of discharge. Studies examining potential predictors of discharge against medical advice should attempt to collect data across all variable domains outlined in this review (that is, patient, provider, and temporal). These studies should be succeeded by follow-up studies to examine how patients discharged in this manner function in the community. Newer statistical packages and techniques make it unnecessary for researchers to rely on univariate analyses. Discriminant function analysis and logistic regression techniques, for example, are available in most statistical packages and are perfectly suited to help determine which variables discriminate between two or more naturally occurring groups.

Two areas have remained relatively unexplored in the body of research on discharge against medical advice. Namely, our search revealed but one publication on an intervention for discharge against medical advice. The literature would greatly benefit from more publications describing successful interventions. Also, because provider-patient dynamics appear to play an important role in discharges against medical advice, qualitative investigations into the phenomenology of discharge should be helpful in gaining a more intimate understanding of the interpersonal processes involved in discharge against medical advice.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to Shayna Marks, Jennifer Cogswell, Jacob Wegelin, and Edward Callahan for their help in the research and in the preparation of this article.

1. Talbott JA: Lessons learned about the chronic mentally ill since 1955, in Exploring the Spectrum of Psychosis. Edited by Ancill RJ, Holliday S, Higenbottom J. London, Wiley, 1994 [reprinted in Psychiatric Services 55:1152-1159, 2004]Google Scholar

2. Brown P: The transfer of care: psychiatric deinstitutionalization and its aftermath. Boston, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985Google Scholar

3. Goldman HH: The demography of deinstitutionalization, in Deinstitutionalization. Edited by Bachrach LL. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1983Google Scholar

4. Turner JE: The chronic patient: perspectives from the 29th Institute on Hospital and Community Psychiatry: defining a community support system (proceedings). Hospital and Community Psychiatry 29:31-32, 1978Google Scholar

5. Quanbeck C, Frye M, Altshuler L: Mania and the law in California: understanding the criminalization of the mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1245-1250, 2003Google Scholar

6. Baekeland F, Lundwall L: Dropping out of treatment: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin 82:738-783, 1975Google Scholar

7. Jeffer EK: Against medical advice: part I, a review of the literature. Military Medicine 158:69-73, 1993Google Scholar

8. Fabrick AL, Ruffin WC Jr, Denman SB: Characteristics of patients discharged against medical advice. Mental Hygiene 52:124-128, 1968Google Scholar

9. Atkinson RM: AMA and AWOL discharges: a six-year comparative study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 22:293-296, 1971Google Scholar

10. Beck NC, Shekim W, Fraps C, et al: Prediction of discharges against medical advice from an alcohol and drug misuse treatment program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 44:171-180, 1983Google Scholar

11. Greenberg WM, Otero J, Villaneuva L: Irregular discharges from a dual diagnosis unit. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 20:355-371, 1994Google Scholar

12. Heinssen RK, McGlashan TH: Predicting hospital discharge status for patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder, and unipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:353-360, 1988Google Scholar

13. Kecmanovic D: Patients discharged against medical advice from a lock-and-key psychiatric institution. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 21:274-281, 1975Google Scholar

14. Lewis JM: Discharge against medical advice: the doctor's role. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:28-32, 1966Google Scholar

15. Phillips MS, Ali H: Psychiatric patients who discharge themselves against medical advice. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 28:202-205, 1983Google Scholar

16. Planansky K, Johnston R: A survey of patients leaving a mental hospital against medical advice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 27:865-868, 1976Google Scholar

17. Raynes AE, Patch VD: Distinguishing features of patients who discharge themselves from psychiatric ward. Comprehensive Psychiatry 12:473-479, 1971Google Scholar

18. Senior N, Kibbee P: Can we predict the patient who leaves against medical advice? The search for a method. Psychiatric Hospital 17:33-36, 1986Google Scholar

19. Tehrani E, Krussel J, Borg L, et al: Dropping out of psychiatric treatment: a prospective study of a first-admission cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 94:266-271, 1996Google Scholar

20. Wylie CM, Michelson RB: Age contrasts in self-discharge from general hospitals. Hospital Formulary 15:273, 276-277, 1980Google Scholar

21. Akhtar S, Helfrich J, Mestayer RF: AMA discharge from a psychiatric inpatient unit. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 27:143-150, 1981Google Scholar

22. Long JP, Marin A: Profile of patients signing against medical advice. Journal of Family Practice 15:551-552, 1982Google Scholar

23. Pages KP, Russo JE, Wingerson DK, et al: Predictors and outcome of discharge against medical advice from the psychiatric units of a general hospital. Psychiatric Services 49:1187-1192, 1998Google Scholar

24. Brush RW, Kaelbling R: Discharge of psychiatric patients against medical advice. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 136:288-292, 1963Google Scholar

25. Johnson DT, Beutler LE, Neville CW: Effects of therapist sex, patient sex, and time on rates of discharge of psychiatric inpatients against medical advice (abstract). Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology 8:88, 1978Google Scholar

26. Tuckman J, Lavell M: Psychiatric patients discharged with or against medical advice. Journal of Clinical Psychology 18:177-180, 1962Google Scholar

27. Piper WE, Joyce AS, Azim HF, et al: Patient characteristics and success in day treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:381-386, 1994Google Scholar

28. LaWall JS, Jones R: Discharges from a ward against medical advice: search for a profile. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:415-416, 1980Google Scholar

29. Dalrymple AJ, Fata M: Cross-validating factors associated with discharges against medical advice. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:285-289, 1993Google Scholar

30. Caton CL: Mental health service use among homeless and never-homeless men with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 46:1139-1143, 1995Google Scholar

31. Chandrasena R: Premature discharges: a comparative study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 32:259-263, 1987Google Scholar

32. Chandrasena R, Miller WC: Discharges AMA and AWOL: a new "revolving door syndrome." Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 13:154-157, 1988Google Scholar

33. Stuen MR, Solberg KB: Maximum hospital benefits vs against medical advice: a comparative study. Archives of General Psychiatry 22:351-355, 1970Google Scholar

34. Harper DW, Elliott-Harper C, Weinerman R, et al: A comparison of AMA and non-AMA patients on a short-term crisis unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:46-48, 1982Google Scholar

35. Greenwald AF, Bartemeier LH: Psychiatric discharges against medical advice. Archives of General Psychiatry 8:117-119, 1963Google Scholar

36. Snyder S, Pitts WM, Pokorny AD: Selected behavioral features of patients with borderline personality traits. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 16:28-39, 1986Google Scholar

37. Daniels RS, Margolis PM, Carson RC: Hospital discharges against medical advice: I. origin and prevention. Archives of General Psychiatry 8:120-130, 1963Google Scholar

38. Woodside DB, Carter JC, Blackmore E: Predictors of premature termination of inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:2277-2281, 2004Google Scholar

39. Green WH, Padron-Gayol M, Whiteman KN, et al: Child psychiatric discharges against medical advice. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 25:260-265, 1986Google Scholar

40. Smith HH Jr: Discharge against medical advice (AMA) from an acute care private psychiatric hospital. Journal of Clinical Psychology 38:550-554, 1982Google Scholar

41. Krakowski AJ: Patients who sign against medical advice. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 10:254-259, 1985Google Scholar

42. Louks J, Mason J, Backus F: AMA discharges: prediction and treatment outcome. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:299-301, 1989Google Scholar

43. Siegel RL, Chester TK, Price DB: Irregular discharges from psychiatric wards in a VA medical center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:54-56, 1982Google Scholar

44. Tessier WG: The impact of ward atmosphere on patient discharge status from locked psychiatric units. Dissertation Abstracts International 50:3178, 1990Google Scholar

45. Syed EU, Mehmud S, Atiq R: Clinical and demographic characteristics of psychiatric inpatients admitted via emergency and non-emergency routes at a university hospital in Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 52:456-459, 2002Google Scholar

46. Sajatovic M, Gerhart C, Semple W: Association between mood-stabilizing medication and mental health resource use in the management of acute mania. Psychiatric Services 48:1037-1041, 1997Google Scholar

47. Greenwald AF: Some contributive factors in psychiatric discharges against medical advice. Psychiatry Digest 24:21-26, 1963Google Scholar

48. Vander Stoep A, Bohn P, Melville E: A model for predicting discharge against medical advice from adolescent residential treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:725-728, 1991Google Scholar

49. Siegel M, Norris CA, Escobar SF: Adolescent discharge against medical advice from a psychiatric hospital. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth 11:35-43, 1994Google Scholar

50. Maddock R, Druff J, Maskowitz MK: Attitude toward hospitalization of patients who leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA). Newsletter for Research in Mental Health and Behavioural Sciences 17:18-20, 1975Google Scholar

51. Singer JE, Grob MC: Patients discharged against medical advice: a follow-up study. Massachusetts Journal of Mental Health 5:57-67, 1974Google Scholar

52. Steinglass P, Grantham CE, Hertzman M: Predicting which patients will be discharged against medical advice: a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:1385-1389, 1980Google Scholar

53. Jeffer EK: Against medical advice: part II, the Army experience 1971-1988. Military Medicine 158:73-76, 1993Google Scholar

54. Lauritsen R, Friis S: Self-rated therapeutic alliance as a predictor of drop-out from a day treatment program. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 50:17-20, 1996Google Scholar

55. Davis WE: The irregular discharge as an unobtrusive measure of discontent among young psychiatric patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 81:17-21, 1973Google Scholar

56. Rinn RC: Effects of nursing apparel upon psychiatric inpatients' behavior. Perceptual and Motor Skills 43:939-945, 1976Google Scholar

57. Schorer CE: Defiance and healing. Comprehensive Psychiatry 6:184-190, 1965Google Scholar

58. McGlashan TH, Heinssen RK: Hospital discharge status and long-term outcome for patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder, and unipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:363-368, 1988Google Scholar

59. Miles JE, Adlersberg M, Reith G, et al: Discharges against medical advice from voluntary psychiatric units. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 27:859-864, 1976Google Scholar

60. Glick ID, Braff DL, Johnson G, et al: Outcome of irregularly discharged psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:1472-1476, 1981Google Scholar

61. Klein E, Cohen RS: Careers of patients discharged against medical advice from St. Elizabeth's Hospital, 1920-1925. Mental Hygiene 11:357-368, 1927Google Scholar

62. Haupt DN, Ehrlich SM: The impact of a new state commitment law on psychiatric patient careers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:745-751, 1980Google Scholar

63. Dixon M, Robertson E, George M, et al: Risk factors for acute psychiatric readmission. Psychiatric Bulletin 21:600-603, 1997Google Scholar

64. Targum SD, Capodanno AE, Hoffman HA, et al: An intervention to reduce the rate of hospital discharges against medical advice. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:657-659, 1982Google Scholar

65. Talbott JA: The fate of the public psychiatric system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:46-50, 1985 [reprinted in Psychiatric Services 55:1136-1140, 2004]Google Scholar

66. Bowers L, Jarrett M, Clark N: Absconding: a literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 5:343-353, 1998Google Scholar

67. Simpson A, Bowers L: Runaway success. Nursing Standard 18:18-19, 2004Google Scholar