Datapoints: Rates of Nonfatal Intentional Self-Harm in Nine States, 2001

According to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center's Web site (1), within the past five years 29 states participated in some funded suicide prevention-related activity. Enactment of the 2004 Garrett Lee Smith act is likely to promote further expansion of state-level prevention programming. As prevention efforts mature in scope and direction, state-level rates of nonfatal suicidal behavior may be one appropriate indicator of effectiveness (2).

Annual rates of nonfatal behaviors are not yet available across all 50 states, and geographic differences in rates have not been well characterized. If these rates are to serve as outcome indicators, additional information is required.

Counts of intentional self injuries treated in emergency departments in 2001 were available from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (2). The report examined the validity of external cause of injury codes (E-coding) associated with primary injury and poisoning diagnoses. We calculated crude event rates per 100,000 U.S. population by using census and fatality data taken from the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (3).

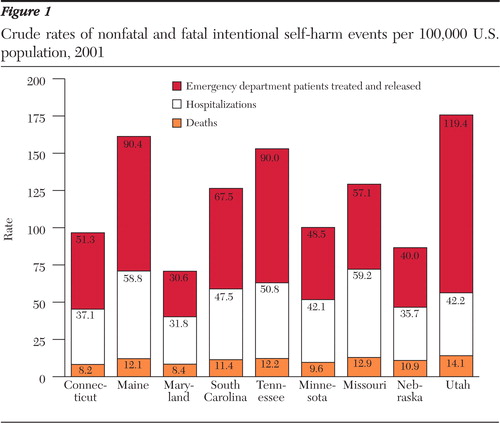

In 2001 medically treated, nonfatal intentional self-injury events were reported 2.5 times as often in Utah as in Maryland (Figure 1). Postinjury hospitalization rates were between 41 and 51 percent of all nonfatal events that were treated in the emergency department. However, when the emergency department rate surpassed 140 events per 100,000 population, hospitalization rates declined. This pattern could be due to geographic variations in the medical seriousness of attempts. Alternatively, as with many other conditions, simply treating larger numbers of events may affect practice patterns.

Our results from this single-year data pool, with its limited number of states are at best preliminary. The fidelity of medical coding, although found to be adequate in the HCUP report, may have been affected by regional differences in reporting practices.

If state-level patterns are found to be stable and reliable, they could inform both policy initiatives and clinical risk assessment. Meaningful comparisons between states can be made only after adjusting for relevant differences, but each state's data serve as an internal control, to mark change and infer the impact of prevention efforts. Regional rate variation may also prove to be clinically relevant when assessing the risk posed by suicidal patients.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines, Dallas, Texas 75390-9119 (e-mail, [email protected]). Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., and Amy M. Kilbourne, Ph.D., M.P.H., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Crude rates of nonfatal and fatal intentional self-harm events per 100,000 U.S. population, 2001

1. State Suicide Prevention Pages. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Available at www.sprc.org/statepages/stateGoogle Scholar

2. Barrett M, Steiner C, Coben J: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) E Code Evaluation Report. HCUP methods series report no 2004-06. US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004Google Scholar

3. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqarsGoogle Scholar