Longitudinal Patterns of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Need and Care in a National Sample of U.S. Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Use of longitudinal data can help clarify the extent of persistent need for services or persistent problems in gaining access to services. This study examined the level of transient and persistent need and unmet need over time among respondents to a national survey and whether need was met by provision of mental health services or resolved without treatment. METHODS: Data from the longitudinal Health Care for Communities (HCC) household telephone survey were used to produce joint distributions of need status and care for two periods (wave 1 data collected in 1997 to 1998 and wave 2 data collected in 2000 to 2001; N=6,659). Perceived need was measured as self-report of need for help with a mental or substance use problem. Probable clinical need was assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey. RESULTS: High levels of persistent unmet need for care (44 to 52 percent) were found among respondents who had probable clinical need in wave 1. Although a majority of those with need received some care, an equal proportion (about 30 percent) of those with perceived need only or probable clinical need in wave 1 did not receive any care. A substantial portion of need (22 to 26 percent) appears to have resolved without treatment, which may suggest high levels of transient need. CONCLUSIONS: Persistent patterns of unmet need represent important targets for policy and programs that can improve utilization, including outreach, education, and improved insurance coverage.

Untreated alcohol, drug, and mental disorders are a major concern among clinicians, consumers, and policy makers because of the personal suffering and associated high social costs (1,2,3,4). National estimates of need and treatment rates can be useful for designing programs and policies by clarifying the scale of unmet need and identifying groups most at risk (5,6,7). Representative national and multisite regional studies, such as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study and the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), indicate that approximately 30 percent of the population will experience a disorder over a period of 12 months.

However, estimates of the need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment are known to be sensitive to the definition of need and treatment, to measurement methods, and to other study design factors (8,9,10,11). For example, differences between the ECA study and the NCS (8,9) in estimates of the prevalence of disorders and unmet need may be due to differences in how the questions are ordered, the survey period, and the diagnostic criteria or inclusiveness of diagnoses. Similarly, estimates of treatment rates vary depending on the definition of treatment—for example, primary care, specialty care, counseling, drug treatment—and the methods of eliciting reports of service use (12,13).

Furthermore, our ability to use these measures to assess persistent unmet need is complicated by the potential for including persons who have transient need and who are likely to recover without treatment (3,14) as well as the potential for not identifying persons who may have a need for services (15). However, longitudinal data can help clarify the extent of persistent need or problems in gaining access to services. Identifying persistent patterns of unmet need can help in the development and improvement of programs and policies, such as insurance coverage, to improve access (3). In addition, measuring persons' perceptions of need may improve estimates of persistent unmet need; and because persons who perceive a need for services have a high propensity to use them (7,16,17,18), measuring perceptions may provide better estimates of service demand for planning and policy purposes.

Using longitudinal data from a representative national household telephone survey, we addressed several questions. How much of the need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment that is measured at a given time point persists 18 months to three years later? To what degree are persistent and transient need met with care over time? In cases in which need is no longer apparent, has the need been met by providing mental health services or has it resolved without treatment? In addition, we addressed the role of perceived need in estimates of need and care. Some respondents who did not perceive a need may have been asymptomatic or in treatment, or they might have benefited from preventive or maintenance treatment. To account for these groups, we compared patterns of care in the group of respondents who perceived a need and the group of respondents who had a probable need for clinical care (and may or may not also have perceived a need). We did not attempt to analyze the effectiveness of treatment, because analyses that use observational data are subject to selectivity bias because of the correlation between the level of distress and the likelihood of seeking treatment (19); such analyses require the use of statistical principles and specific methods for the analysis of observational data (20).

Methods

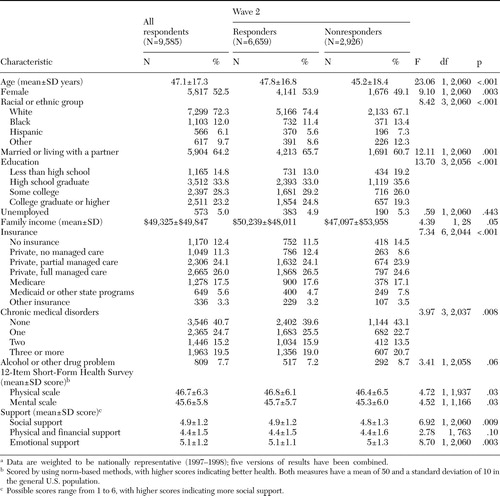

Data sources

We used data that were collected in two waves (1997 to 1998 and 2000 to 2001) of the Healthcare for Communities study (HCC), a collateral study of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) (21,22). The sample eligible for wave 1 of HCC (HCC-1) was a stratified random sample of persons who completed the first wave of the CTS survey (CTS-1). The CTS drew household samples from 60 randomly selected communities in the continental United States and included an unclustered national sample to improve the precision of national estimates. Responses were obtained for 65 percent of the CTS-1 sample. For HCC-1, which was completed about 14 months after CTS-1, a total of 14,985 of the 30,375 adult CTS-1 respondents were randomly selected. The design called for oversampling of persons with high psychological distress; high use of alcohol, drug, or mental health services; and family income below $20,000. A total of 9,585 respondents (64 percent) completed HCC-1. The weighted HCC-1 sample closely matched the 1997 U.S. household population in demographic characteristics (23). A total of 6,659 of the 9,585 HCC-1 respondents (70.9 percent, weighted) completed wave 2 approximately 18 months later. Responders and nonresponders for wave 2 differed significantly on most baseline characteristics (Table 1); however, the small to moderate differences suggested that the samples were sociodemographically similar.

Variables

All the survey items used to derive the analysis variables can be found on the Web site of the University of California, Los Angeles, Health Services Research Center (www.hsrcenter.ucla.edu/research/hcc.shtml). A list of the variables used to derive the analysis variables can be obtained from the authors.

Probable clinical need. Individuals were deemed to have probable clinical need if they screened positive for major depressive, dysthymia, generalized anxiety, or panic disorder; lifetime mania, psychosis, or schizophrenia; alcohol abuse; or recent use of illicit substances. Major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and lifetime mania were defined by DSM-III-R criteria and assessed with use of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview short form (CIDI-SF), which has excellent sensitivity and specificity (90 to 100 percent concordance) compared with the full CIDI (24). To reduce potential false-positives for panic disorder on this instrument, we required that the respondent be limited in social or role functioning as measured by two items from the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey and three items from the Sickness Impact Profile (25).

Lifetime psychosis was assessed by asking respondents if they had ever stayed overnight in a hospital for psychotic symptoms. Probable schizophrenia was assessed by asking respondents if they had ever been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder by a physician. Although the psychosis and schizophrenia measures have not been validated, they are adequate for use in a community sample in which one would not expect to find many people with serious mental illness. Alcohol abuse was assessed with use of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), for which the World Health Organization has reported sensitivities ranging from 92 to 94 percent and specificities ranging from 80 to 89 percent (26,27). Illicit drug use was assessed by using items from the CIDI (28).

Perceived need. Perceived need was indicated by an affirmative response to one or both of the following items: "In the past 12 months, did you think you needed help for emotional or mental health problems, such as feeling sad, blue, anxious, or nervous?" "In the past 12 months did you think you needed help for alcohol or drug problems?" (23). Although these items have not been validated, similar items were used in the NCS and other psychiatric epidemiologic studies (16,29). In the NCS, 32 percent of persons who had disorders perceived a need for help, and perceived need mediated differences in service use (29). In the HCC-1 sample, only about 4 percent of respondents perceived a need for treatment without having a probable clinical disorder (Table 1).

Any alcohol, drug, or mental health care. HCC collected detailed information on medication use, hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders, mental health care from primary care and specialty providers, and substance abuse care from primary and specialty care providers. From these items we developed an indicator that identified respondents who in the previous 12 months had had any contact with a primary or specialty care provider for a mental health problem—including inpatient, day treatment, or residential care for an alcohol, drug, or mental health problem—or who had an emergency department or outpatient visit to a general medical or alcohol, drug, or mental health specialty provider for assessment, monitoring, counseling, referral, or medication (30).

Analysis

To assess the level of transient and persistent need and unmet need, we examined joint distributions of alcohol, drug, and mental health need and care across HCC waves. Using the indicators for perceived and probable clinical need, we categorized the sample according to three levels of need: no perceived or probable clinical need, perceived need only, and probable clinical need (alone as well as accompanied by perceived need). We also categorized the sample according to care patterns: none in either wave, care in wave 1 only, care in wave 2 only, and care in both waves. We used this category design to address some of the problems noted above in using cross-sectional data to assess "clinically significant" need. Because perceived need only (asymptomatic) may be indicative of a potential clinical need (either past or future), this category is useful for identifying respondents with potential need that could develop into persistent unmet clinical need if left untreated.

HCC used a complex multistage sampling design with unequal selection probabilities, clustering, and sampling without replacement. All analyses were performed with SUDAAN software for the statistical analysis of correlated data (31), which takes the survey design into account when estimating standard errors. We used multiple imputations for missing items (32). Percentages in all tables are weighted to be representative of the wave 1 national sample.

Results

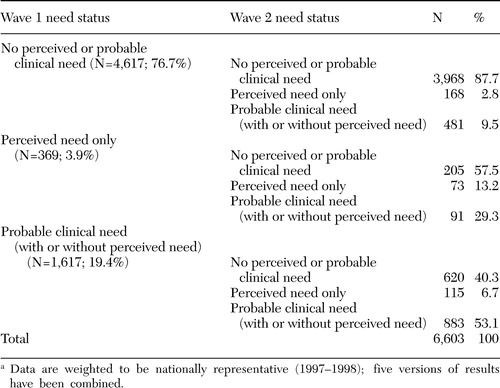

We examined patterns of need over time without adjusting for care received. As shown in Table 2, about 40 to 60 percent of wave 1 need was transient. A lower proportion of those with wave 1 perceived need only experienced need in wave 2, as compared with those with wave 1 probable clinical need. Wave 1 perceived need translated into future probable clinical need for about 30 percent of respondents with wave 1 perceived need. However, for more than half of respondents with wave 1 probable clinical need, this need was persistent over time.

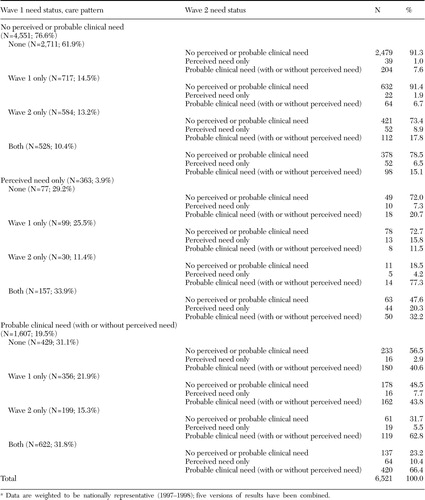

As shown in Table 3, of the respondents who had no perceived or probable clinical need in wave 1, about 40 percent received some form of care (monitoring, assessment, or treatment) in wave 1, wave 2, or both. Furthermore, the probability of having need in wave 2 was higher among those who received care in wave 2 or in both waves, compared with those who received no care or who received care in wave 1 only. Although wave 1 respondents with perceived need only accounted for less than 4 percent of the sample, the overall pattern of need and care for this group was remarkably similar to that of the wave 1 respondents with probable clinical need. Approximately 70 percent of need in these two groups was met with some form of care in wave 1 or wave 2 or both. Furthermore, among respondents who received care in wave 2 or in both waves, wave 1 respondents with perceived need only and wave 1 respondents with probable clinical need had a high rate of persistent need—that is, need in both wave 1 and wave 2.

To test the sensitivity of our results to our definition of alcohol, drug, and mental health care, we also examined patterns of need and service use by using a narrower definition of care that included only visits or care that contained some potentially effective treatment, such as counseling or medication. This pattern of need and treatment was similar to the care patterns shown in Table 3, and thus we only briefly summarize the results here. As would be expected with a narrower definition of care, slightly smaller proportions of respondents received treatment in wave 1, wave 2, or both, regardless of need. However, among wave 1 respondents with probable clinical need, a higher proportion in all treatment pattern subgroups had some form of need in wave 2, compared with the wave 1 clinical need and care pattern subgroups described above.

Discussion

In this study, we explored longitudinal patterns of alcohol, drug, and mental health need and care in order to estimate levels of persistent need and unmet need. We also examined the role that perceptions of need played in these estimates. We found that respondents who received care in wave 2 only or in both waves were more likely than those who received no care in wave 1 only to demonstrate persistent need. We also found high levels of persistent unmet need for care (44 to 52 percent) among wave 1 respondents who had probable clinical need. Although a majority of those with need in both waves were receiving some care, about 30 percent of those with perceived need only and 30 percent of those with probable clinical need did not receive any care, which suggests a substantial level of unmet need.

Furthermore, the substantial portion of need that appears to have resolved without treatment (58 percent of wave 1 respondents with perceived need and 40 percent of those with wave 1 probable clinical need) may suggest high levels of transient need. We found some evidence to suggest that respondents who screen asymptomatic on the basis of diagnostic interviews may be managing their disorder through treatment. For example, a relatively large proportion (about 38 percent) of those with no wave 1 need received care, including monitoring and assessment, at some point. A small proportion received care in both waves (10 percent), and three-quarters of this group had no perceived or probable clinical need in wave 2. Clinical need may not be apparent among those who are receiving treatment and managing their alcohol, drug, or mental health problem successfully as a consequence or among those who have a disorder that is currently inactive who may still require periodic monitoring and assessment. A complete history of alcohol, drug, and mental health problems, including context, symptoms, severity, and persistence, is necessary to accurately determine need. However, inclusion of perceived need in measures of need may be one way to capture the cases missed by diagnostic screens.

Our results also suggest that perceived need that is not accompanied by probable clinical need could be an indicator of a mild or developing disorder. We found that a small proportion of perceived need was persistent across waves (about 13 percent). However, more than half of wave 1 perceived need was resolved by wave 2; and almost one-third of respondents with wave 1 perceived need experienced probable clinical need in wave 2. Among wave 1 respondents with perceived need only who either received no care or received care in wave 1 only, more than one-fourth demonstrated subsequent need and may have benefited from receiving more consistent care—that is, care in both waves. More than 50 percent of probable clinical need was persistent across waves. Almost half of wave 1 probable clinical need appeared to have resolved or to have been met by care in wave 2 or in both waves. Not surprisingly, probable clinical need was less likely than perceived need only to be resolved with no care or with care in wave 1 only.

This study has two important limitations. The first involves the precision of the screening measures used in the analysis. HCC, a study with moderate costs, used an approach to measuring need and care that facilitated a broad and rough estimate of need and unmet need; however, HCC does not have the precision and comprehensiveness of a study such as the NCS. It is likely that some milder forms of need that might merit evaluation but not necessarily treatment were included. Accordingly, we used a broad indicator of care (including monitoring, assessment, and specific treatments) to gauge whether need was met.

The screens used in HCC for the more common disorders have been previously used and validated, but the more serious disorders (psychosis and schizophrenia) were assessed with a single item. These single-item measures are less precise than a full battery of items to assess psychosis and schizophrenia, such as that used by the NCS. In addition, our measure of need did not include some disorders, such as phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Thus we also report estimates of perceived need (without probable clinical need) using items similar to those used by the NCS for assessing perceived need in order to capture need not assessed by the screens used in HCC. Because no other national longitudinal studies for the U.S. population have been published, we cannot determine how the imprecision of our need measure may have affected our estimates of transient and persistent need. Our results may slightly underestimate the extent of some disorders and overestimate that of others in the noninstitutionalized population.

In fact, when weighted cross-sectional estimates from HCC-1 (N=9,585) of specific 12-month disorders are compared with estimates from NCS (N=8.098) (33), HCC rates are slightly lower for major depressive disorder (9.1 percent compared with 10.3 percent) and higher for dysthymia (4.1 percent compared with 2.5 percent), generalized anxiety disorder (3.7 percent compared with 3.1 percent), panic disorder (3.4 percent compared with 2.3 percent), and psychosis (1.1 percent compared with .5 percent). Our 12-month prevalence rate for any disorder (Table 2) is slightly lower than 12-month prevalence estimates from the NCS; however, our measure does not include all the disorders (phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder) included in the NCS estimates, which could explain this difference.

Conversely, our measure for any care used detailed data (self-report) on medication, counseling, hospitalizations, and similar variables and included care received in primary and specialty care settings as well as emergency departments. This measure was intended to capture a broad range of care, including monitoring and assessment, as well as effective treatments (such as medication and specific counseling techniques) and may have resulted in lower estimates of unmet need. Using NCS data and a narrower definition of treatment, Kessler and colleagues (6) reported a treatment rate of 46.2 percent for those with serious mental illness, 18.3 percent for those with other mental disorders, and 6.3 percent for those with no disorders (6). Our results suggest that almost 70 percent of respondents with wave 1 probable clinical need (Table 3) received some form of care within the HCC data collection time frame (three to four years). Thus it appears that our results may be an underestimate the extent of unmet need in the noninstitutionalized population.

The second limitation is our moderate response rate, especially when multiplied across the two data waves. Responders and nonresponders differed; however, in most cases the statistically significant differences between responders and nonresponders were very small. Furthermore, our analyses incorporated nonresponse weights that accounted for statistically significant demographic differences between responders and nonresponders (technical documentation at www.hsrcenter.ucla.edu/research/hcc.shtml). Because weighted analyses may not correct all bias due to nonresponse, and HCC nonresponders may have been more likely to have alcohol, drug, or mental disorders, our longitudinal estimates of need may be slightly lower than would have been the case had the nonresponders been included. Estimates of any disorder in the past 12 months from the NCS and the ECA study range from 20 to 30 percent of the population, depending on the criteria applied, and our (weighted) estimates for any probable clinical disorder of 19.5 percent for wave 1 and 18.7 percent for wave 2 are only slightly lower. However, our estimates did not include phobias, which the NCS and ECA estimates did, and this may explain some of this difference.

Conclusions

Unmet need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment and the associated burden of illness have a substantial impact on both individuals and society in terms of the costs of lost productivity and unmeasured personal suffering. Although national estimates based on cross-sectional data can provide a relatively good basis for policy and service planning, the accuracy and validity of measures of persistent, unmet need could be improved with longitudinal data. This study presented estimates of transient, persistent, and unmet need for alcohol, drug, and mental health problems from a national longitudinal survey of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Because of serious data limitations, these results should be considered preliminary until future longitudinal data are available to replicate them. Nevertheless, our estimates are within range of existing estimates based on previous cross-sectional studies (the NCS and the ECA) and thus provide a reasonably good assessment of transient and persistent need and unmet need in the noninstitutionalized U.S. population.

If replicated, our results suggest that a substantial proportion of need may be transient and may not require long-term care. However, some persons who do not screen positive for a disorder may benefit from receiving at least periodic monitoring and assessment. Persistent patterns of unmet need represent important targets for policy and programs that can improve utilization, including outreach, education, and improved insurance coverage. To determine treatment effects under conditions of selectivity bias, future analyses with longitudinal data should explore other methodologic techniques to reduce the effects of bias, such as the use of instrumental variables or propensity scoring techniques. Such analyses would be particularly useful for service planning by predicting levels of transient and persistent need based on population characteristics and patterns of treatment. In addition, such analyses could be used to estimate more precisely what proportion of need is transient and can be resolved quickly with treatment and how much need is persistent, requiring extended treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lingqi Tang, Ph.D., and Cathy Sherbourne, Ph.D., for their contributions to the conceptualization of the analysis variables, technical assistance, and helpful comments. This research was supported by grant 038273 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and grant P30MH068639:01 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Stockdale, Dr. Klap, Ms. Zhang, and Dr. Wells are affiliated with the Health Services Research Center of the Semel Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, 10920 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 300, Los Angeles, California 90024 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Wells is also with the health program at RAND in Santa Monica. Dr. Belin is with the department of biostatistics at the UCLA School of Public Health.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the respondents to wave 1 of the Health Care for Communities survey by wave 2 responsesa

a Data are weighted to be nationally representative (1997-1998); five versions of results have been combined.

|

Table 2. Need status of respondents to the Health Care for Communities survey at wave 1, by need status at wave 2a

a Data are weighted to be nationally representative (1997-1998); five versions of results have been combined.

|

Table 3. Need status at wave 1 of respondents to the Health Care for Communities survey, by care pattern and need status at wave 2a

a Data are weighted to be nationally representative (1997-1998); five versions of results have been combined.

1. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:914–919,1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, et al: The most expensive medical conditions in America. Health Affairs 21(4):105–111,2002Google Scholar

3. Mechanic D: Is the prevalence of mental disorders a good measure of the need for services? Health Affairs 22(5):8–20,2003Google Scholar

4. Callahan D: Balancing efficiency and need in allocating resources to the care of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:664–666,1999Link, Google Scholar

5. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlate of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987–1007,2001Medline, Google Scholar

7. World Health Organization: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, et al: Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:109–115,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al: Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:115–123,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Spitzer RL: Diagnosis and need for treatment are not the same. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:120,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, First M: "Clinical significance" and DSM-IV. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1145,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gresenz CR, Stockdale SE, Wells KB: Community effects on access to behavioral health care. Health Services Research 35:293–306,2000Medline, Google Scholar

14. Regier DA: Mental disorder diagnostic theory and practical reality: an evolutionary perspective. Health Affairs 22(5):21–27,2003Google Scholar

15. Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al: The prevalence of treated and untreated disorders in five countries. Health Affairs 22(3):122–132,2003Google Scholar

16. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. New England Journal of Medicine 336:551–557,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Ontario. Inquiry 34:38–50,1997Medline, Google Scholar

18. Mechanic D, Bilder S: Treatment of people with mental illness: a decade-long perspective. Health Affairs 23(4):84–95,2004Google Scholar

19. Miranda J, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne C, et al: Effects of primary care depression treatment on minority patients' clinical status and employment. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:827–834,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rosenbaum PR: Observational Studies. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1995Google Scholar

21. Sturm R, Gresenz C, Sherbourne C, et al: The design of Healthcare for Communities: a study of health care delivery for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Inquiry 36:221–233,1999Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan JM, et al: The design of the community tracking study: a longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people. Inquiry 33:195–206,1996Medline, Google Scholar

23. Sturm R, Sherbourne CD: Are barriers to mental health and substance abuse care still rising? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 28:81–88,2001Google Scholar

24. Kessler RC, Andrew G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Ware JE, Kosinksi M, Keller SF: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220–233,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al: Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction 88:791–804,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): guidelines for use in primary care, 2nd ed. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

28. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1995Google Scholar

29. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Sturm R, et al: Alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health care for uninsured and insured adults. Health Services Research 37:1055–1066,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. SUDAAN: Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data, version 7.5. Cary, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

32. Little RJA, Rubin DB: Statistical Analysis With Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2002Google Scholar

33. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar