A Pharmacy-Based Coaching Program to Improve Adherence to Antidepressant Treatment Among Primary Care Patients

Abstract

The effects on adherence and depressive symptoms of a community pharmacy-based coaching program, including a take-home videotape, were evaluated in a randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands. A total of 147 depressed primary care patients who had a new antidepressant prescription were included in the study. Adherence was measured with an electronic pill container and was also derived from pharmacy medication records; the latter method was associated with an overestimation of adherence of only 5 percent. Intention-to-treat analyses showed no intervention effect on adherence (73 percent compared with 76 percent), whereas analyses of patients who received the intervention (per protocol) showed improved adherence (73 percent compared with 90 percent). Neither analysis showed effects on depressive symptoms.

The effectiveness of antidepressants is reduced by nonadherence. Many factors contribute to nonadherence, including intrinsic pharmacologic characteristics of the antidepressants—for example, adverse effects—disease-related variables, and patient and prescriber characteristics (1). Positive expectations and a belief in the benefits and efficacy of treatment have proved essential to adherence. It is therefore believed that coaching patients about taking their medications and informing patients with depression about what to expect can improve adherence (2). The aim of this study was to improve adherence to nontricyclic antidepressant regimens among patients with depression through a pharmacist intervention.

Methods

The study was a randomized controlled trial with six-month follow up. From April 2000 to April 2001 a total of 19 community pharmacists in various regions of the Netherlands asked for written informed consent of consecutively attending patients of general practitioners who were 18 years or older, who had a new prescription for a nontricyclic antidepressant, and who were able to fill out questionnaires in Dutch.

All patients received their antidepressants in an electronic pill container called an eDEM when they picked up their prescriptions. This type of pill container has an electronic device in the cover that records each opening of the box by day, hour, and minute. Patients in the intervention group were offered three coaching contacts, which lasted between ten and 20 minutes. The pharmacists were asked to use a list of important themes to discuss with the patients (3). In addition, the patients in the intervention group received a 25-minute take-home video emphasizing the importance of adherence. With use of block randomization at the patient level, the data administration forms for the whole sample were randomized before delivery to the pharmacies. The pharmacist learned the patient's group assignment after written informed consent had been received. The study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the University Medical Centre of Utrecht.

The primary outcome (adherence) was continuously measured over a six-month period by using eDEMs as well as computerized patient medication records kept by the pharmacies. We calculated correct medication intakes as the number of recorded openings of the eDEM divided by the number of monitored days in the prescription period (usually 182 days, but sometimes shorter, depending on the prescription period per patient).

The pharmacists registered each delivered class of medication per patient, the number of pills, the date that the prescription was actually filled, and the date on which the patient had to come to the pharmacy to refill the container. We estimated the adherence of each patient by subtracting the number of days that the patient had been overdue in picking up the antidepressants at the pharmacy from the overall six-month adherence. The comparison with the eDEM recordings showed an overestimation of adherence of 5 percent in the pharmacy records. For the 28 patients for whom only the pharmacy registration was available, we subsequently reduced estimated adherence by 5 percent.

Depressive symptoms were measured at baseline and at three- and six-month follow-up with the self-reported 13-item depression subscale (SCL-13) (4).

Both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed to estimate the effectiveness and the efficacy of the intervention, respectively. The following protocol criteria were used. The antidepressant had to be prescribed by a general practitioner, the patient had to indicate that he or she had watched the videotape, and the patient had to receive three coaching contacts: at baseline, after two weeks (allowing a one-week margin, for a follow-up period of one to three weeks), and after 12 weeks (allowing a three-week margin, for a follow-up period of nine to 15 weeks). The analyses were performed both for patients who completed the study and for the whole group (by using imputed data). In the case of patients with missing data at three-month follow-up (N=29) and at six-month follow-up (N=38), we used group mean imputation within the intervention group and the control group, separately.

In the intended sample of 150 patients (75 patients per group), a difference in adherence of 13 percent would be detectable at a significance level of .05 (two-sided) with a probability of 80 percent and assuming a standard deviation in adherence of 40 percent. (Difference was assessed as a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 100 percent.)

Results

Of the 46 pharmacists who were approached in 1999 to participate in the study, 26 initially agreed, and 19 actually participated. A total of 147 patients were initially included, of whom 135 (92 percent) returned the baseline questionnaire and were included in the intention-to-treat analyses. The patients were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (64 patients) or the control group (71 patients). No significant differences between the groups on demographic or health-related variables were noted at baseline.

Of the total study population of 147 patients, 29 (20 percent) dropped out within three months, and 38 (including the aforementioned 29) (26 percent) dropped out within six months. Those who completed the study reported initially that they had significantly more faith in the effectiveness of the antidepressants (77 percent) compared with those who dropped out (23 percent) (χ2=10.036 df=1 p=.002).

No baseline differences in demographic or clinical characteristics were noted. The patients' mean±SD age was 43±13 years. A total of 95 patients (70 percent) were women, and 111 (82 percent) had moderate to severe symptoms as rated by their general practitioners. Additional baseline characteristics of the sample have been reported previously (2).

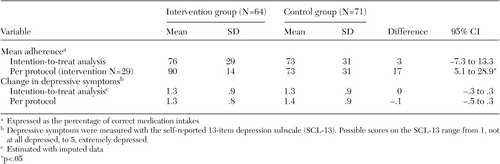

The intervention effects on the main outcomes (adherence and depressive symptoms) are reported in Table 1. Only the per-protocol analysis indicated significantly better adherence in the intervention group than in the control group. Neither analysis showed effects on depressive symptoms.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings indicated that brief coaching contacts by pharmacists, together with an informative videotape, improved neither adherence to antidepressant regimens nor depressive symptoms in the initial sample. However, patients who received care according to the intended protocol had significantly better adherence than the control group. No accompanying effects on depressive symptoms were found. In addition, adherence rates based on pharmacy records were shown to be valid when compared with the eDEM estimates.

An important limitation of this study was the fact that a relatively small number of patients in the intervention group received the protocol as intended. The contrast between the groups should therefore be interpreted with caution. In addition, patients in both groups were given electronic pill containers, which by itself could be said to have constituted an adherence intervention. Thus patients in both groups were aware that their adherence was being closely monitored, which may have reduced the contrast between the groups. Consequently, we may have failed to detect a possible intervention effect.

Compared with patients who completed the study, those who dropped out made a more negative appraisal of the effectiveness of the antidepressant medication, which demonstrates the importance of patients' treatment expectations. A final possible limitation was that neither the patients nor the pharmacists were blinded to the randomization of patients within the pharmacies. Although we carefully trained the pharmacists, this limitation may have contaminated the usual care of the patients in the control group and reduced the contrast between the groups.

Pharmacy records, although less detailed in terms of monitoring times, have several advantages over eDEMs in measuring medication adherence. Pharmacy records include data for all drugs dispensed, which enables monitoring of adherence to multiple medications, whereas eDEMs can monitor only one type of drug at a time. In addition, pharmacy records provide a more complete, practical, and less intrusive method for assessing and monitoring adherence to all drugs dispensed.

Dr. Brook is affiliated with the Dutch Society for Surgeons, Postbox 20061, 3502 LB Utrecht, The Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. van Hout, Dr. Stalman, and Dr. de Haan are with the department of general practice of the Emgo Institute at VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam. Dr. Nieuwenhuyse is with the International Health Foundation in Utrecht. Dr. Bakker is with the department of psychiatry of Sint Lucas Andreas Hospital in Amsterdam. Dr. Heerdink is with the department of pharmacotherapy and epidemiology of University Utrecht.

|

Table 1. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on adherence and depressive symptoms in a sample of primary care patients in the Netherlands

1. Donoghue J, Hylan TR: Antidepressant use in clinical practice: efficacy v effectiveness. British Journal of Psychiatry 179 (suppl 42):9–17, 2001Google Scholar

2. Brook OH, van Hout H, Nieuwenhuyse H, et al: The impact of coaching by community pharmacists on drug attitude of depressive primary care patients and acceptability to patients. European Neuropsychopharmacology 13:1–9, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lin EHB, von Korff M, Katon W, et al: The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Medical Care 3:67–74, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Lipman RS, Covi L, Shapiro AK: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). Journal of Affective Disorders 1:9–24, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar