Brief Reports: A Comparison of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the GAF Among Adults With Mental Retardation and Mental Illness

Abstract

Psychiatric assessment among individuals with a diagnosis of both mental retardation and mental illness presents a clinical challenge. This retrospective study compared two rating scales—the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)—to determine the scales' utility in a partial hospital setting. Although ABC and GAF ratings were weakly correlated, the ABC revealed symptom patterns consistent with recognizable features of psychiatric syndromes and differential improvement in symptoms within and between diagnostic subgroups. The ABC provided a more useful measure of treatment response than the GAF in this patient population.

The prevalence of psychiatric illness among adults with mental retardation is substantial—as high as 40 percent in demographic surveys (1). The challenges inherent in recognizing and treating mental illness in this population are complex and escalate with decreasing IQ (2). Individuals with mental retardation often lack the communication skills and introspective capacity to accurately report their experience of psychiatric symptoms or changes in the severity of symptoms (3). Thus psychiatric diagnosis and assessment of clinical change in this population does not easily lend itself to the use of available psychiatric rating scales.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (4), the most widely used scale for rating the severity of mental illness, is a required element of the medical record. However, this scale relegates individuals with mental retardation—and, by definition, its inherent deficits in adaptive functioning—to the lowest range of scores. In other words, GAF ratings are skewed as a result of a ceiling effect that results in a constricted range when applied to persons who have both mental retardation and mental illness.

The Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) (5), widely used to monitor an array of behavioral features among patients with mental retardation, was developed for use in institutions but has been applied among adults with mental retardation who are living in community settings (6). The ABC relies entirely on clinical observations of activity and behavior without regard to the underlying etiology or function of the observed phenomena. Thus the ABC downplays the role of self-reported data, covers a wide range of features, and disregards the issue of psychiatric diagnosis.

Available experience with the ABC in an adult psychiatric setting is limited to a pilot study of 36 patients with mild mental retardation and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (7) in which 40 percent of the patients showed improvement on all five ABC subscales at discharge compared with admission, whereas 60 percent had mixed results. To our knowledge, no other published reports have provided data on psychiatric treatment outcomes among patients with both mental retardation and mental illness on the basis of the ABC. Given that an increasing proportion of current psychiatric practice involves treatment of psychiatric symptoms among patients with mental retardation, there may be an enhanced role for rating scales such as the ABC.

The study reported here focused on the use of both the ABC and the GAF among adults with mental retardation and a comorbid DSM-IV axis I psychiatric diagnosis (8) who received psychiatric treatment in a developmental disabilities-oriented partial hospital setting. The study addressed two issues: whether baseline and outcome (change from baseline) measures were correlated between the ABC and the GAF, and whether ABC and GAF ratings differed among psychiatric diagnostic categories.

Methods

This retrospective chart-review study, which was approved by the hospital's institutional review board, examined medical record data from 72 consecutively treated psychiatric partial hospital patients of the developmental disabilities program at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, during the two-year period from January 1998 to December 1999. Each patient had a psychiatric diagnosis and comorbid intellectual disability and lived in the community. The specialized psychiatric treatment setting at this developmental disabilities-oriented partial hospital has been described elsewhere (9). ABC and GAF data were available in the medical record for all 72 patients.

Associations between demographic variables, diagnosis, and ABC and GAF baseline (admission), endpoint (discharge), and change-from-baseline (outcome) ratings were assessed by using Spearman rank-based correlation methods and random-effects regression modeling. The random effects were the study participants, and the fixed effects were diagnosis, time, and other covariates of interest (10). Model fits were checked by examining partial residual plots. For some assessments of correlations between measures with skewed distributions, nonparametric Spearman rank-correlation methods were used. Statistical significance was set at p<.05 (two-tailed).

Results

The patients were evenly divided by gender (36 women and 36 men), ranged in age from 19 to 62 years (mean±SD age of 37.2±10 years), were largely Caucasian (65 patients, or 90 percent; five, or 7 percent, were African American, and two, or 3 percent, were Hispanic), and had a diagnosis of mild mental retardation (69 patients, or 96 percent) or borderline intellectual functioning (three patients, or 4 percent). Psychiatric diagnoses were grouped into four categories: bipolar disorder (ten patients, or 14 percent), major depressive disorder (27 patients, or 37 percent), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (30 patients, or 42 percent), and impulse-control disorders (five patients, or 7 percent). The schizophrenia spectrum category comprised schizophrenia (eight patients, or 27 percent), schizoaffective disorder (14 patients, or 47 percent), and schizophreniform disorder (one patient, or 3 percent).

For the group of 72 patients, all five of the ABC subscale scores at discharge were significantly different from the scores on these measures at admission (mean change of -4.58± 6.84, z=5.03, p<.001). GAF ratings also improved substantially over the course of the treatment, with mean improvement of 8.4±9.4 points (z= -7.6, p<.001). (Possible scores on the GAF range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning; possible subscale scores on the ABC range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating more behavioral impairment.)

Changes in ABC and GAF ratings over time were only weakly correlated (r=-.23 to .16). For only one of the ABC subscales—irritability—was the correlation with GAF change from baseline statistically significant (t=-2.01, df=70, p=.048). Similarly, changes in ABC subscales over time were very weakly correlated with GAF-rated severity of illness at baseline (data not shown).

Baseline, endpoint, and change-from-baseline scores on the ABC and the GAF did not differ significantly by sex. In addition, scores for men and women did not differ significantly on any of these measures within or between diagnostic categories.

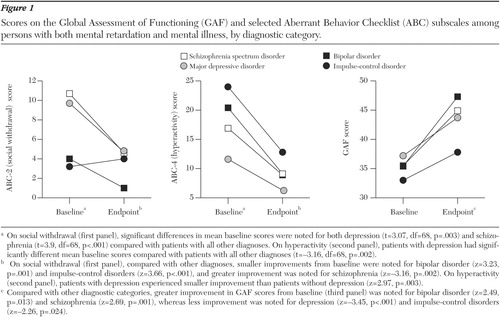

Baseline and endpoint scores for the GAF and selected ABC subscales, by diagnostic category, are shown in Figure 1. At baseline, there were no significant differences between diagnoses on the basis of the GAF. However, in contrast, there were substantial differences at baseline on the basis of the ABC subscales. For the change-from-baseline outcome, substantial differences between diagnoses were noted on both the GAF and the ABC subscales among the four diagnostic categories.

Discussion

The use of the ABC subscales rather than the composite GAF rating to identify and track improvement in clinical symptoms within specific psychiatric diagnostic categories among persons with concurrent mental retardation and mental illness is, to our knowledge, a novel application of the ABC. In this study, no significant differences were found between diagnostic categories on GAF ratings at admission, but there were substantial differences on the ABC subscales. Thus heterogeneous levels of psychopathology among these patients at the onset of treatment, when rated by the GAF alone, appeared to be homogeneous.

However, when we used the ABC subscales, a more descriptive picture emerged—and one that was consistent with clinical experience. For patients who present with depression or schizophrenia, social withdrawal is a conspicuous hallmark of the illness, and this finding was clearly apparent in this study. Thus the ABC appears to identify salient features of mental illness in this population of patients, both within and between diagnostic categories.

The ABC subscales, and to a lesser extent the GAF, also provided a credible summary of symptomatic improvement over time in this population. When we compared ABC ratings, it was evident that, although the patients with depression and schizophrenia experienced more social withdrawal at admission and that patients with bipolar disorder and impulse-control disorders presented with greater hyperactivity, each diagnostic group achieved differential improvement in symptoms. These descriptive findings confirm clinical symptom presentations and patterns of improvement that are consistent with recognized psychiatric phenomenology, regardless of the contribution of mental retardation.

Conclusions

The conclusions of this study are necessarily limited by the study's retrospective and unblinded design and the heterogeneity of ongoing clinical treatment in this partial hospital setting. However, this work indicates that, for individuals with a diagnosis of mild mental retardation and comorbid psychiatric illness, the ABC subscales can be meaningfully applied both for the initial assessment of psychiatric symptoms and for monitoring of these symptoms over the course of treatment. Whereas an increasing number of persons with mental retardation are being treated in community practice settings, we believe that the ABC rating scale can be helpful to clinicians in the development of psychiatric practice parameters for persons with both mental retardation and mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Doherty, M.F.A., Mary Jo Iacoboni, B.S.N., R.N., Robert Sisson, Ph.D., Edwin J. Mikkelsen, M.D., and the Manzi Foundation for their efforts and support of this project.

Dr. Shedlack is affiliated with the developmental disabilities program and Dr. Hennen with the biostatistics laboratory of McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, Massachusetts 02478 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Magee is with May Behavioral Health in Norwood, Massachusetts. Mr. Cheron is with Boston University and at the time of this study was affiliated with Boston College. This paper was presented in part at the annual meeting of the National Association of Dual Diagnosis, held October 24 to 27, 2001, in New Orleans, and at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held May 18 to 23, 2002, in Philadelphia. This brief report is part of a special section on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

Figure 1. Scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and selected Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) subscales among persons with both mental retardation and mental illness, by diagnostic category.

1. Dosen A, Day K: Epidemiology, etiology, and presentation of mental illness and behavior disorders in persons with mental retardation, in Treating Mental Illness and Behavior Disorders in Children and Adults With Mental Retardation. Edited by Dosen A, Day K. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001Google Scholar

2. Mikkelsen EJ, McKenna L: Psychopharmacologic algorithms for adults with developmental disabilities and difficult-to-diagnose behavioral disorders. Psychiatric Annals 29:302–314, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Sovner R, Hurley AD: Four factors affecting the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in mentally retarded persons. Psychiatric Aspects of Mental Retardation Reviews 5:45–48, 1986Google Scholar

4. Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV): Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

5. Aman MG, Richmond G, Stewart AW, et al: The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: factor structure and the effect of subject variables in American and New Zealand facilities. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 91:570–578, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

6. Aman MG, Borrow WH, Wolford PL: The Aberrant Behavior Checklist-community: factor validity and effect of subject variables for adults in group homes. American Journal on Mental Retardation 100:283–292, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

7. Luiselli JK, Benner S, Stoddard T, et al: Evaluating the efficacy of partial hospitalization services for adults with mental retardation and psychiatric disorders: a pilot study using the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC). Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities 4:61–67, 2001Google Scholar

8. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV): Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

9. Shedlack KJ, Chapman RA: Social learning interventions in a developmental disabilities partial hospital program. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 7:7–25, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Greene WH: Econometric Analysis, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice Hall, 2000Google Scholar