Health Service Use Among Persons With Comorbid Bipolar and Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study tested the hypothesis that patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders use health services to a greater extent than patients with either bipolar or substance use disorder alone. METHODS: A retrospective chart review was conducted among patients who used health services at the Ralph H. Johnson Department of Veterans Affairs medical center in Charleston, South Carolina, and had bipolar disorder alone, substance use disorder alone, and comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders. Patients with a psychiatric admission between 1999 and 2003 were included in the study. Information was collected on the use of health services one year before and including the index admission. RESULTS: The records of 106 eligible patients were examined for this study: 18 had bipolar disorder alone, 39 had substance use disorder alone, and 49 had both bipolar and substance use disorders. Compared with the other two groups, the group with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders was significantly more likely to be suicidal. Compared with the group with bipolar disorder alone, the group with comorbid disorders had significantly fewer outpatient psychiatric visits and tended to have shorter psychiatric hospitalizations. Among patients with an alcohol use disorder, those who also had bipolar disorder were significantly less likely than those with an alcohol use disorder alone to have had an alcohol-related seizure. Patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders were significantly less likely than those with substance use disorder alone to be referred for intensive substance abuse treatment, even though both groups were equally likely to enter and complete treatment when they were referred. CONCLUSIONS: Despite significant functional impairment among patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders, they had significantly fewer psychiatric outpatient visits than those with bipolar disorder alone and were referred for intensive substance abuse treatment significantly less often than those with substance use disorder alone.

Several studies have demonstrated the extraordinarily high prevalence of co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders. The Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study (N=20,291) reported that 56 percent of individuals with bipolar disorder have a substance use disorder (1). In both the ECA study and the National Comorbidity Survey (N=8,098), bipolar disorder was the axis I condition most commonly associated with a substance use disorder (1,2). Comorbid substance use disorder negatively affects the course, treatment outcome, and prognosis of bipolar disorder. Individuals with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders have more frequent hospitalizations (3,4,5), earlier onset of illness (3,6), and more depressive or mixed-manic episodes (6,7). These comorbid conditions may delay recovery from affective episodes (7,8) and are likely to lead to increased health service use and costs.

Several investigators have studied the patterns of service use among patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders. Simon and Unützer (9) reported that psychiatric and substance abuse services accounted for 45 percent of total costs in a group of 1,346 insured individuals with bipolar disorder. Dickey and Azeni (10) found that individuals with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders had treatment costs nearly 60 percent greater than those who did not have a substance use disorder (N=1,493). The cost difference was due primarily to greater acute inpatient psychiatric care. Additionally, individuals with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders have more visits to the emergency department (11). However, to our knowledge no studies have specifically investigated service use among individuals with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders, nor have studies compared those with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders with those who have either bipolar or substance use disorder alone. There is clearly a need to better characterize and understand the patterns of service use among patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorder to identify factors contributing to increased health care costs.

This study was a retrospective chart review of patients in a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center (VAMC) with bipolar disorder alone, substance use disorder alone, and comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders. The study was designed to examine clinical characteristics and patterns of service use. We hypothesized that patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders would use a variety of health services to a greater extent than those with either bipolar or substance use disorder alone.

Methods

Medical records were examined for patients admitted to the psychiatric unit of the Ralph H. Johnson VAMC between 1999 and 2003 with discharge diagnoses of bipolar disorder or alcohol use disorder. Diagnoses were identified by DSM-IV codes. Records were cross-referenced so that individuals were included in data collection only once. Records were reviewed by the principal investigator (MLV) to confirm the diagnosis. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of the Medical University of South Carolina and the VAMC. Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study.

Our study examined service use in the year before admission, so records were excluded if the patients had not been followed primarily by the VAMC for at least one year before admission. Records with primary diagnoses of major depression, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or substance-induced mood disorder were also excluded. We chose to exclude substance-induced mood disorder for uniformity of the sample, because this term can refer to either unipolar or bipolar mood episodes, and data from these patients would, therefore, obscure the primary focus on bipolar disorder. Patients with a single diagnosis of alcohol use disorder were included if they had current alcohol use (used alcohol in the past three months). Comorbid psychiatric conditions were allowed, including anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and other nonaffective, nonpsychotic disorders.

The index admission served as the collection point for data on demographic characteristics, descriptive characteristics, current medications, and laboratory tests. Data on the use of health services were collected for the year before and including the index admission. The VAMC where this study was conducted has an inpatient psychiatric unit, inpatient medical and surgical services, an outpatient mental health clinic, outpatient primary care and specialty clinics, social services, urgent care and emergency services, and an intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment center. Additionally, outpatient psychiatric and primary care clinics are available in two outlying locations.

In particular, data were collected on referral to the substance abuse treatment center and on the use of psychiatric, case management, primary care, specialty care, the emergency department, and inpatient services. For patients who received occasional outpatient care from a non-VAMC location, health service use was estimated on the basis of available data. If a patient received treatment primarily from non-VAMC providers, he or she was excluded. For patients who were hospitalized at non-VAMC locations, the length of stay during that hospitalization was recorded as five days.

Records were classified into three groups: bipolar disorder without a substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder (with or without other substance use) without affective or psychotic disorders, and comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders. Patients with bipolar disorder who were not currently using substances were included in the group with bipolar disorder alone.

Demographic data were compared between groups by using standard descriptive statistics. Because of the limited sample for some comparisons, nonparametric and exact tests were also employed. If 25 percent or more of the cells in a contingency table had an expected cell count less than five, Fisher's exact test was used.

The Kruskal-Wallis test, a nonparametric alternative to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model, was implemented for the hospital use variables, because the observed data failed distributional assumptions of a one-way ANOVA model. Post-hoc comparisons of group scores were conducted by using Kruskal-Wallis tests if the overall omnibus Kruskal-Wallis test was significant. To account for the multiple indexes related to health care use, a .01 level of significance was established. Fisher's protected least significant difference at a .01 level of significance was used for the post-hoc comparisons. A less rigorous level of .05 was used for secondary analyses, including the description of group differences with respect to baseline and clinical characteristics. All analyses were compiled with SAS version 9.1.

Results

A total of 310 patient records were identified with an eligible discharge diagnosis. Of these records, 204 (66 percent) were excluded for the following reasons: less than one year of notes or the patient was "missing" during the year before admission (143 patients, or 46 percent), no outpatient notes were in the medical record (103 patients, or 33 percent), the medical record was coded as "sensitive" and was not accessible for research (54 patients, or 17 percent), and other (24 patients, or 8 percent). These categories were not mutually exclusive, and as a result some of the records were excluded for more than one reason. A total of 106 records satisfying inclusion criteria were grouped into the following diagnostic categories: bipolar disorder alone (18 patients, or 17 percent), comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders (49 patients, or 46 percent), and substance use disorder alone (39 patients, or 37 percent).

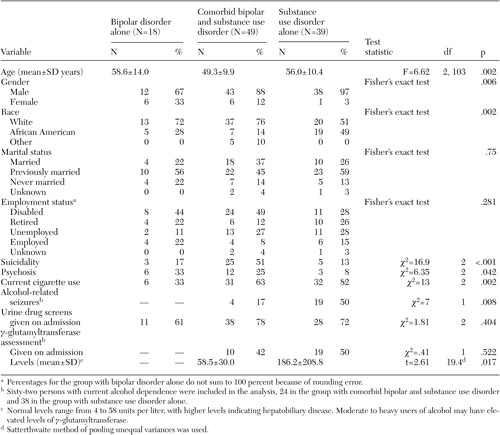

Table 1 presents key demographic and clinical characteristics by diagnostic group. The group with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders was significantly younger, the group with bipolar disorder alone had proportionally more women, and the group with substance use disorder alone had the largest percentage of African Americans. No statistically significant differences were found in marital status, employment status, or percentage of patients with a service-connected disorder. The group with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders had the highest percentage of suicidality on admission. The group with bipolar disorder alone had the highest percentage of psychosis and was the least likely to currently use cigarettes. Although the three groups did not differ statistically in whether they had urine toxicology tests performed on admission, it is notable that among all the groups, 29 patients (27 percent) did not have a urine toxicology test performed on admission; among the group with bipolar disorder alone, seven patients (39 percent) were not given a urine toxicology test on admission.

A subgroup analysis was conducted that consisted of only patients with current alcohol dependence from the group with comorbid diagnoses (24 patients, or 49 percent) and the group with a substance use disorder alone (38 patients, or 97 percent). The rate of γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) testing was comparable between the two groups, but patients with current alcohol dependence in the substance use disorder group had higher mean GGT levels and a higher rate of alcohol-related seizures.

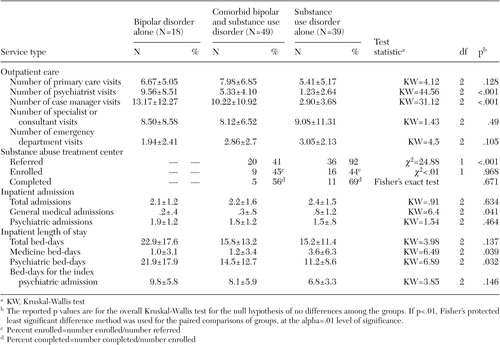

As shown in Table 2, for health service use, patients with bipolar disorder alone had the highest number of psychiatric and case manager outpatient visits. Other measures of outpatient care, including primary care, specialist visits, and emergency department visits, did not differ significantly. Although the overall number of inpatient bed-days did not differ significantly, trends were seen toward different patterns of inpatient use between groups. In particular, the group with substance use disorder alone tended to have the highest number of general medicine inpatient bed-days, whereas the group with bipolar disorder alone and the group with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders tended to have more psychiatric inpatient bed-days. The same general patterns were observed for the number of inpatient admissions. Although group differences were approaching significance in the number of general medicine admissions, the overall number of medical and psychiatric admissions did not differ by group.

Patients in the group with substance use disorder alone were significantly more likely than those in the group with comorbid diagnoses to be referred to the substance abuse treatment center for treatment. However, among patients referred to the center, no significant differences were found between the two groups in the percentage of patients who entered or completed treatment. In each group, just under one-half of the patients referred entered the substance abuse treatment center, and one-quarter to one-third of those referred completed the program. A majority of referrals occurred during the index psychiatric admission.

Discussion

In this study we compared the use of health services, demographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to a psychiatric unit with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders, bipolar disorder alone, and substance use disorder alone. Consistent with previous reports, patients with co-occurring disorders were significantly younger than those with either bipolar or substance use disorder alone (12). Other investigators have reported an earlier onset of affective episodes among individuals with bipolar disorder who use substances (6).

Although the VAMC population is primarily male, more women were in the group with bipolar disorder alone. This finding could reflect a smaller proportion of women seeking substance abuse treatment from the VAMC or a smaller proportion of women with substance use disorders in this VAMC population.

We also found differences in racial characteristics between groups. A majority of individuals with bipolar disorder alone and with co-occurring disorders were white, whereas only half of those with substance use disorder alone were white. This finding may represent underdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among African Americans with substance use disorders.

Patients with co-occurring disorders were significantly more likely than those in the other two groups to be suicidal on admission; more than half this group endorsed suicidality. This finding is consistent with previous reports of more depressive and mixed manic episodes associated with substance use among persons with bipolar disorder (6,7) and greater association of suicidality with these types of affective states (13). This clinical issue is important because active substance use is a clear risk factor for completed suicide, which highlights the need for careful screening for suicidality among patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders.

Some of the most interesting data are related to service use. Patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders used psychiatric services significantly less than those with bipolar disorder alone (p=.008). Because of the large and consistent body of literature indicating a more severe and chronic course of illness among patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders, we had predicted a greater use of health services among these patients. However, some authors have reported shorter hospital stays for individuals with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders (14,15), and others report that differences in health care costs between patients with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders and other psychiatric patients tend to decrease over time (12). Others have reported that length of inpatient stay for individuals with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders may not be generalizable across diagnoses, hospitals, states, or types of insurance (16).

We expected to find differences between the groups in whether they had comorbid medical conditions and treatment patterns. Surprisingly, the only statistically significant finding was that patients with substance use disorder alone were significantly more likely than those with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders to have alcohol-related seizures. Several reasons could account for this finding. GGT levels were three times as high among patients with substance use disorder alone as among those with comorbid disorders, suggesting that those with substance use disorder alone were heavier users of alcohol. This finding may reflect an increased sensitivity to psychosocial and psychiatric impairment from alcohol among patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders, resulting in drinking becoming more problematic with lower levels of use. It is also possible that treatment with mood stabilizers, specifically antiepileptic agents, is prophylactic against seizures and leads to decreased alcohol consumption among individuals with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders.

Patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders were seen by psychiatrists significantly less often than those with bipolar disorder alone, perhaps reflecting less compliance with treatment and follow-up. It is also possible that psychiatrists are more likely to establish a therapeutic alliance with patients who are not actively abusing substances. Patients with bipolar disorder alone tended to have longer psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations than those in the other two groups, despite the fact that more than half of those with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders endorsed suicidality and nearly one-quarter presented with psychosis. It may be that active substance use played a role in the exacerbation of the affective symptoms and suicidality that led to the need for admission. Substance-induced symptoms often resolve fairly quickly with abstinence, which may explain the shorter hospital stay for the group with co-occurring disorders.

Patients with substance use disorder alone received significantly less outpatient psychiatric care than those in the other two groups. This finding could reflect noncompliance with treatment recommendations or the referral patterns of primary care physicians. Substance use is often inadequately addressed in outpatient primary care (17), which leads to individuals' not being referred for treatment. This finding is consistent with the fact that a majority of referrals to the substance abuse treatment center occurred during inpatient psychiatric admissions rather than over the course of routine outpatient care. Patients with substance use disorder alone did not have greater use of primary care services, despite the fact that they tended to use inpatient medical services to a greater extent than patients in the other two groups. This observation may reflect the fact that individuals with substance use disorder not only require more medical care but wait to seek services until their problems require more acute and intensive treatment.

The most striking findings were related to referral for treatment of substance use disorders. Ninety-two percent of patients with substance use disorder alone were referred to the substance abuse treatment center, whereas only 41 percent of those with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders were referred for such treatment. Furthermore, patients in both groups who were referred for substance abuse treatment were equally likely to enter and complete treatment. This finding clearly argues for more aggressive assessment and referral for substance abuse treatment among patients with bipolar disorder. The pervasive idea that patients with bipolar disorder are less likely to attend, benefit from, or complete substance abuse treatment was not supported by our data. Given the strong association between suicidality and substance use, it is particularly important to refer individuals with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders for substance abuse treatment as early as possible.

Although no statistically significant differences were found between the groups in whether they were given a urine toxicology test on admission, it is notable that 27 percent of the entire sample and 39 percent of patients with bipolar disorder alone did not have urine toxicology tests performed during psychiatric admission. Deferring such tests among acutely ill patients with bipolar disorder who are admitted to an inpatient unit is of concern. It is clear that substance use and withdrawal could be contributing factors in exacerbation of affective symptoms, suicidality, and medication noncompliance that often lead to the need for hospitalization. Information about substance use is necessary to make well-informed long-term treatment decisions, and many individuals are reluctant to admit to substance use during admission. Given the prevalence and negative impact of substance use among persons with bipolar disorder (3,4,5,6,7), routine urine toxicology tests should be given to acutely ill patients with bipolar disorder.

This study had a number of limitations. This was a retrospective chart review, so it was not possible to assess accuracy of diagnoses or obtain additional information about service use beyond that recorded in the chart. For instance, it is unclear whether variations in service use reflect noncompliance with treatment recommendations or a lack of availability to certain populations. Additionally, the point of identification for participants in this study was an inpatient psychiatric admission, so this population was relatively sick, which may limit the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, hospitalization thresholds may differ among individuals with bipolar disorder alone and those with bipolar disorder and co-occurring substance use. For example, clinicians may be more likely to admit persons with bipolar disorder who use substances and have a lower severity of affective symptoms, whereas persons with bipolar disorder without substance use may not be admitted until their affective symptoms are more severe. Therefore, the groups we compared may have differed in terms of severity of illness. Finally, collection of data from before admission provides information about patterns of service use and clinical presentation leading to acute inpatient treatment but does not necessarily reflect patterns of service use after an acute psychiatric hospitalization.

Regarding statistical limitations, multiple statistical tests on service use outcomes were used. To compensate, a more restrictive level of significance (alpha=.01) was implemented. The small sample and unequal group sizes also limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. In future studies, enlisting additional VAMCs might help increase statistical power and generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Despite significant functional impairment in terms of suicidality and psychosis, patients with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorders had fewer outpatient psychiatric visits and tended to spend fewer days in the psychiatric inpatient unit than those with bipolar disorder alone and were significantly less likely to be referred for substance abuse treatment than those with substance use disorder alone. A significant percentage of patients with bipolar disorder alone did not have urine toxicology tests performed, despite the high association between substance use and bipolar disorders. Careful assessment of substance use among individuals with bipolar disorder and referral for treatment will be important to improve outcomes for this population. Prospective studies examining health service use would be of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Frye, M.D., at the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute for his consultation for the development of this study. This study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Janssen Pharmaceutica that was presented through the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, 67 President Street, P.O. Box 250861, Charleston, South Carolina 29425 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Carter is also with the department of biostatistics, bioinformation, and epidemiology the Medical University of South Carolina. Dr. Myrick is also with the department of psychiatry at the Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration Medical Center in Charleston. Findings from this study were presented at the Research Colloquium for Junior Investigators at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 1 to 6, 2004, in New York City.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 106 patients admitted to the psychiatric unit of a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center, by discharge diagnosis

|

Table 2. Service use for the year before and including index admission among 106 patients admitted to the psychiatric unit of a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center, by discharge diagnosis

1. Reiger DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Blanco-Perez CR, Blanco C, Grimaldi JAR, et al: Substance abuse and bipolar disorder, in Proceedings from the American Psychiatric Association. New York, 1996Google Scholar

4. Brady KT, Casto S, Lydiard RB, et al: Substance abuse in an inpatient psychiatric sample. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 17:389–397, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Reich LH, Davies RK, Himmelhoch JM: Excessive alcohol use in manic-depressive illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 131:83–86, 1974Link, Google Scholar

6. Sonne SC, Brady KT, Morton WA: Substance abuse and bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:34–352, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, et al: Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. JAMA 255:3138–3142, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Strakowski SM, Keck PE, McElroy SL, et al: Twelve-month outcome after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:49–55, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Simon GE, Unützer JU: Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatric Services 50:1303–1308, 1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973–977, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, et al: Emergency department use of persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Annals of Emergency Medicine 41:659–667, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Long-term patterns of service use and cost among patients with both psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Medical Care 36:835–843, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sato T, Bottlender R, Tanabe A, et al: Cincinnati criteria for mixed mania and suicidality in patients with acute mania. Comprehensive Psychiatry 45:62–69, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck R, Massari L, Astrachan B, et al: Mentally ill chemical abusers discharged from VA inpatient treatment:1976–1988. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:237–249, 1990Google Scholar

15. Lyons JS, McGovern MP: Use of mental health services by dually diagnosed patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1067–1069, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Bradley CJ, Zarkin GA: Inpatient stays for patients diagnosed with severe psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. Health Services Research 31:387–408, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ: Primary care physicians' views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: inconsistencies with national guidelines. Journal of Family Practice 48:899–902, 1999Medline, Google Scholar