Depression and Comorbid Pain as Predictors of Disability, Employment, Insurance Status, and Health Care Costs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Individuals with depression commonly experience pain with unclear pathology. This study examined depression and comorbid pain and associated outcomes over six years in a nationally representative cohort of older Americans. METHODS: The Health and Retirement Study began in 1992 and follows 9,825 individuals between the ages of 50 and 61 years. The study reported here used data beginning in 1994 to contrast individuals with depression and those with depression plus comorbid pain. Regression models adjusted for differences in sociodemographic characteristics and health status. RESULTS: Baseline (1994) data were available for 8,280 participants. At baseline, 65.2 percent reported that they did not have pain or depression, 8.1 percent had depression alone, 15.5 percent had mild or moderate pain alone, 2 percent had severe pain alone, 6.6 percent had depression plus mild or moderate pain, and 2.6 percent had depression plus severe pain. Compared with the group with no pain or depression, all the groups with depression, pain, or both had greater decrements in outcomes. Groups tended to have greater decrements in outcomes as levels of pain increased. Overall, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups with depression plus pain and their corresponding groups with pain alone. Two to six years after baseline, compared with participants with depression alone, those with severe pain or depression plus severe pain were more likely to experience new functional limitations and to have higher total health care expenditures. Compared with participants with depression alone, participants with depression plus severe pain were also more likely to lose employment and private health insurance. CONCLUSIONS: Relative to depression alone, depression plus pain and pain alone (particularly severe pain) were associated with significant functional limitations and economic burdens.

Pain, often with unclear pathology, co-occurs frequently among individuals with clinically significant depressive symptoms, complicating both the recognition and treatment of depression (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). Over time, psychiatric disorders predict the onset of physical symptoms, and, in turn, physical symptoms, especially pain, predict the onset of depression (10,11,12). Unfortunately, compared with individuals with depression alone, those with depression and comorbid pain are significantly less likely to seek mental health specialty care and are more likely to incur higher total health care costs and use complementary and alternative treatments with questionable effectiveness (13).

Temporal patterns of depression and pain have been studied in large community surveys (10,11), but few data exist on long-term functional and socioeconomic outcomes, even though patients highly value such outcomes (14). We analyzed whether individuals with depression and comorbid pain in the Health and Retirement Study were more likely than those with depression alone to become physically disabled, become limited in their ability to work, leave employment, lose private insurance, or have higher medical expenses over time.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal national survey of individuals born between 1931 and 1941 (15). The HRS was initiated in 1992 to track national trends biennially in health and economic well-being among retired and near-retired Americans. Mental health status has been measured consistently since 1994. At that time 8,807 individuals, or 89.6 percent of the initial sample, responded. The average age of respondents was 57 years in 1994. In 2000 a total of 7,992 participants were reinterviewed, for an overall retention rate of 76.3 percent. The average age of respondents was 63 years in 2000. Deaths were relatively infrequent over the years studied and were not a primary cause of nonresponse.

To assess mental health status, the HRS uses an eight-item version of the depression scale developed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES-D) (16). This scale measures depressive symptoms in the past seven days, including feeling depressed, feeling as though everything is an effort, having restless sleep, having the inability to "get going," feeling lonely, feeling sad, enjoying life (reverse coded), and feeling happy (reverse coded), combined into a scale with possible scores ranging from 0 to 8. For our analysis, participants were said to have depression if they scored 3 or more on the scale. This value indicates significant depressive symptoms and gives a sensitivity of approximately 70 percent and a specificity of 80 percent compared with the Short Form Composite International Diagnostic Interview clinical screener for depression (17,18). Univariate sensitivity analyses estimated models with one-symptom and five-symptom cut-off points; our models were not sensitive to these changes in the specification.

To identify pain, respondents were asked whether they often experienced pain, without reference to physical pathology ("Are you often troubled with pain?"), and about the severity of pain (mild or moderate pain compared with severe pain). Sensitivity analyses indicated that the association between the dichotomous pain measure, depression, and the dependent variables was sensitive to pain severity, with different relationships in the group with severe pain compared with the group with mild or moderate pain.

We created a three-level categorical measure for pain, ranging from 0, no pain, to 2, severe pain. We combined this measure with the dichotomous depression variable, which resulted in a six-level categorical variable that distinguished all combinations of pain and depression. We controlled for the presence of physician-diagnosed diabetes, hypertension, cancer, stroke, heart disease, and lung disease by using an ordinal variable of the number of these conditions reported by participants, and we controlled for arthritis with a separate indicator. Thus we estimated the effects of pain and depression while holding the presence of specific medical conditions constant.

Univariate sensitivity analyses separately estimated models for participants without any chronic conditions and with two or more conditions and for participants with and without arthritis; our models were not sensitive to these alternate specifications.

Dependent variables

Onset of limitations in activities of daily living. At each follow-up year, participants were asked to rate their level of difficulty in performing any of five different tasks: bathing, eating, dressing, walking across a room, and getting into or out of bed. Only individuals who reported no limitations at baseline were assessed to determine how depression with or without pain affected the probability and number of new functional limitations.

Onset of work disability. Participants responded to a dichotomous item at each follow-up year that asked whether health problems currently limited them in the type or amount of paid work that they could do. Only individuals who reported no work limitations at baseline were included in this analysis.

Changes in employment status. We classified individuals as "working" or "not working" at each follow-up period, and focused on the probability of a participant's making a transition from working at baseline to not working at the follow-up periods. Only participants who were employed in 1994 were included in the analysis. (There were not enough persons at baseline who were unemployed or retired who later reentered the labor force to conduct an analysis of making a transition out of unemployment.)

Loss of private insurance. Participants' insurance status was collected at each follow-up period and categorized as uninsured, privately insured, or receiving Medicaid. We examined only individuals with private health insurance (that is, insurance provided by either their employer or their spouse's employer) at baseline to study the probability of losing private insurance at follow-up periods.

Medical expenditures. The HRS imputed total medical expenditures for the two years before each interview. We summed total costs (measured in 1996, 1998, and 2000) and controlled for expenditures for the two years before 1994. Medical expenditures included self-reported estimates of two-year costs for hospital stays, nursing home stays, and doctor visits. Follow-up questions allowed participants to make estimates within broad brackets, enabling HRS to impute missing values. These estimates captured total costs, not just out-of-pocket costs.

Analyses

All analyses were performed with Stata version 7.0 (19). We compared six groups: depression plus mild or moderate pain, depression plus severe pain, depression alone, mild or moderate pain alone, severe pain alone, and neither depression nor pain. Our discussion of results emphasizes any differences between patients with depression alone and those with depression and comorbid pain, either mild or moderate pain or severe pain. Post hoc Wald tests were used to empirically assess these contrasts. To control for confounding differences in socioeconomic status and other health problems, we used multivariate analyses: logistic regression models for dichotomous variables (work limitation, private insurance status, and employment status), ordered logit regression for the number of limitations in activities of daily living, and a loglinear model for log costs.

Covariates included age, race or ethnicity (white, black, and other), gender, employment status (except where this was a dependent variable), log of household income, lifetime years of education, current marital status (married or cohabiting with a partner, and other), and presence of chronic health conditions and arthritis during the past two years. For medical costs, we also included medical costs in the two years before 1994 to control for baseline expenses.

Coefficients in nonlinear models are not easily interpreted, so we also provide predicted values of the dependent variable. These predicted values adjust for confounding differences in baseline sociodemographic characteristics and medical conditions and are standardized to be nationally representative for this age range. For medical costs we retransformed the predicted values on the log scale to real dollars with Duan's smearing estimator (20). The hypothesis of homoskedastic log errors across the six groups, which was important for the consistency of the retransformation, was not rejected by a Glesjer's test (21). All the analyses except for those of medical costs were conducted for 1996, 1998, and 2000—that is, each individual could contribute up to three observations. Medical costs were analyzed as the sum of the 1996 through 2000 observations.

Results

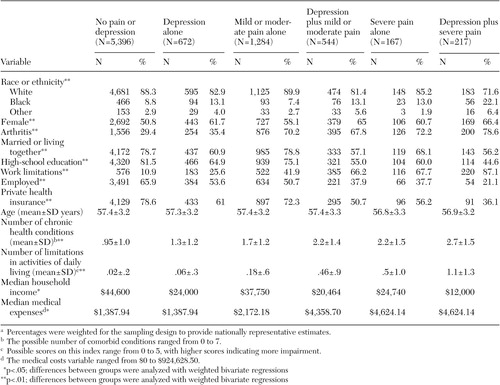

Descriptive analyses (not adjusted for the presence of arthritis or chronic health problems) of baseline characteristics of the HRS sample are depicted in Table 1. Data were available for 8,280 respondents at baseline. In 1994, a total of 5,396 (65.2 percent) reported that they did not have pain or depression, 1,284 respondents (15.5 percent) reported mild or moderate pain alone, 167 (2 percent) reported severe pain alone, 672 (8.1 percent) reported depressive symptoms alone, 544 (6.6 percent) reported depression plus mild or moderate pain, and 217 (2.6 percent) reported depression plus severe pain. A majority of participants with depression (761 respondents, or 53.1 percent) also reported comorbid pain. One of the most dramatic differences between the six groups was in the percentage of respondents who reported that health limited their ability to work. Compared with respondents with depression alone, those with depression and comorbid pain were more likely to report such work limitations (χ2=1,277.86, df=5, p<.01).

The mean number of limitations in activities of daily living was significantly higher in the group with depression plus severe pain than in the other groups (χ2=855.20, df=5, p< .01). Approximately three-quarters of participants with severe pain alone and those with depression plus severe pain reported a lifetime diagnosis of arthritis; these proportions were significantly higher than those found in the other groups (χ2= 865.92, df=5, p<.01).

These four groups differed in other characteristics as well. Compared with the group with depression alone, the group with depression plus severe pain had lower educational achievement (χ2=349.86, df=5, p<.01) and more chronic health conditions (χ2= 1,067.01, df=5, p<.01). Also, compared with participants with depression alone, fewer individuals with depression plus severe pain were employed (χ2=331.97, df=5, p<.01) or had private health insurance (χ2= 364.48, df=5, p<.01). The group with severe pain and the group with depression plus severe pain also had higher medical expenditures at baseline (β=3,236.20, p<.01). Additionally, multivariate analyses (not shown) indicated that persons with depression plus pain at baseline (especially severe pain) were more likely than the other groups to have depression at each follow-up point.

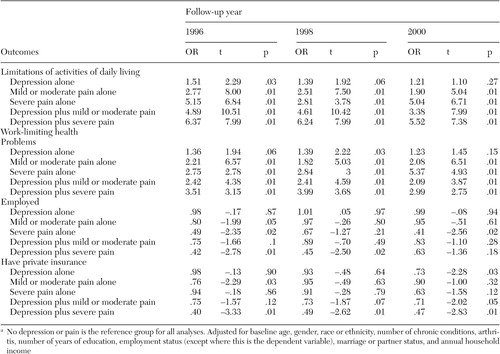

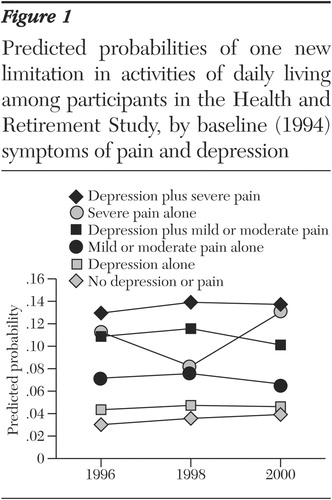

As shown in Table 2, when the analyses adjusted for baseline characteristics, all the groups with depression, pain, or both were significantly more likely than the group without pain or depression to have a limitation in activities of daily living in 1996, 1998, and 2000; the only exception was for the group with depression alone in 1998 and 2000. The group with depression plus severe pain was more likely than the other groups to experience a limitation in activities of daily living for all the follow-up years.

As shown in Figure 1, the probability of one new limitation in the activities of daily living was highest among those with depression plus severe pain compared with the other groups. Post hoc Wald tests confirmed that compared with the group with depression alone, the group with depression plus mild or moderate pain had a significantly greater probability of a new limitation for all the follow-up years (1996, χ2=34.21, df=1, p<.01; 1998, χ2= 38.26, df=1, p<.01; 2000, χ2=25.22, df=1, p<.01). The probability of a new limitation was also significantly greater in the group with depression plus severe pain compared with the group with depression alone for all the follow-up years (1996, χ2=29.25, df=1, p<.01; 1998, χ2=33.04, df=1, p<.01; 2000, χ2=32.10, df=1, p<.01). Post hoc tests that contrasted the groups with depression alone and with depression plus mild or moderate pain as well as the groups with severe pain alone and with depression plus severe pain did not show significant differences at any of the follow-up years.

As shown in Table 2, all the groups with depression, pain, or both were significantly more likely than the group without depression or pain to have work-limiting health problems in the follow-up years; the only exception was for the group with depression alone in 1996 and 2000. The group with depression plus severe pain was more likely than the other groups to experience work-limiting health problems for all the follow-up years; the only exception was that the group with severe pain alone was more likely than the group with depression plus severe pain to experience these limitations in 2000.

Predicted probabilities of onset of these limitations were highest in the group with severe pain alone (.19 in 1996, .24 in 1998, and .42 in 2000) and in the group with depression plus severe pain (.23 in 1996, .31 in 1998, and .30 in 2000). The 2000 finding is counterintuitive in that the group with severe pain alone was more likely than the group with depression plus severe pain to have a greater risk of work-limiting health problems; however, a Wald test indicated that the coefficient estimates corresponding to these two groups were not significantly different. Similarly, other Wald tests contrasting the groups with depression plus pain with their corresponding groups with pain alone were not significant. Relative to the group with depression alone, the group with depression plus mild or moderate pain (1996, χ2=5.70, df=1, p<.02; 1998, χ2=5.96, df=1, p<.02; 2000 χ2=5.57, df=1, p<.02) and the group with depression plus severe pain (1996, χ2=5.09, df=1, p<.03; 1998, χ2=7.17, df=1, p<.01; 2000, χ2= 4.56, df=1; p<.04) were significantly more likely to experience a work-limiting health problem at all the follow-up points.

As shown in Table 2, despite the adverse effects on functioning, depression alone and depression plus pain had less relation to the probability of remaining employed, although mild or moderate pain alone and severe pain alone were associated with decreased odds of employment in 1996 and severe pain alone was associated with reduced odds of employment in 1996 and 2000. Depression plus severe pain was associated with reduced odds of employment in 1996 and 1998.

Predicted probabilities of employment were lowest in the group with depression plus severe pain (.63 in 1996, .49 in 1998, and .43 in 2000). Post hoc contrasts between the group with depression alone and the group with depression plus mild or moderate pain were not significant at any time point; the group with depression plus severe pain was significantly less likely than the group with depression alone to be employed in 1996 (Wald χ2=6.34, df=1, p<.02) and 1998 (χ2=5.63, df=1, p<.02), although not in 2000.

Similarly, depression and pain were weakly related to loss of private health insurance (Table 2). Depression alone was significantly associated with the odds of losing insurance only in 2000, and mild or moderate pain alone was significantly associated with loss of insurance only in 1996. Participants with depression plus severe pain were less likely to have private insurance in all the follow-up years; those with depression plus mild or moderate pain were less likely to be privately insured in 2000.

Predicted probabilities of having insurance were lowest in the depression plus severe pain group at all three follow-up points (probabilities ranged from .62 to .74). As with employment, the likelihood of losing private insurance did not differ significantly between the groups with depression alone and with depression plus mild or moderate pain, and the group with depression plus severe pain was more likely to lose insurance than the group with depression alone in 1996 (χ2=8.48, df=1, p<.01) and 1998 (χ2=4.6, df=1, p<.04). Post hoc contrasts of the groups with depression plus pain with their corresponding groups with pain alone were not significantly different for either employment or insurance.

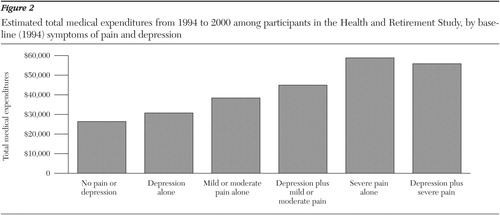

Finally, mild or moderate pain alone, severe pain alone, and depression alone were each significantly associated with greater total medical expenses after the analyses controlled for baseline characteristics. As shown in Table 3, persons with depression, pain, or both had significantly higher expenses than those without these conditions. The predicted values in Figure 2 indicate that compared with participants with depression alone, those with depression plus mild or moderate pain had mean total costs that were approximately $14,200 higher (F=17.09, df=1, 6,336, p<.01) and costs for those with depression plus severe pain were approximately $25,100 higher (F=23.11, df=1, 6,336, p<.01). The group with severe pain alone had the highest estimated medical costs (approximately $3,000 higher than among participants with depression plus severe pain). However, a Wald test indicated that the coefficient estimates for the group with severe pain alone and the group with depression plus severe pain were not significantly different. Other comparisons of coefficients for the group with depression plus mild or moderate pain and the group with mild or moderate pain alone were not significant.

Discussion

We analyzed functional and socioeconomic outcomes associated with depression and pain over six years among older individuals (average age of 63 years in 2000). After the analyses controlled for individual sociodemographic characteristics and medical conditions at baseline, compared with depression alone, depression plus pain—either mild or moderate pain or severe pain—was associated with significantly higher rates of new limitations in activities of daily living and work-limiting health problems over time. However, differences between groups with depression plus pain and their corresponding groups with pain alone were generally not significant. After controlling for differences in baseline characteristics, we also found very large differences between the groups in health care costs over six years.

Despite the strong relationship between depression, pain, and physical disability and health care costs, results for employment and insurance were less powerful. Many older individuals leave the workforce for reasons unrelated to pain or depression, and making a transition into Medicare may render private insurance less relevant to overall coverage, although it remains important for medication coverage. Additionally, these transitions are complicated by the fact that individuals with depression plus pain were less likely to be employed or to have private insurance at baseline. Still, our analyses indicated that persons with depression plus severe pain were more likely to lose employment and insurance over time, relative to those with depression alone. This appears to be the first study based on nationally representative (although age-restricted) survey data that examined long-term functional and social consequences of depression and comorbid pain. The results suggest that functional disabilities are likely an important component of social costs.

The typical limitations of large longitudinal surveys apply here, although they are secondary to the limitations of health status measurement. Attrition was surprisingly small for a survey with such a long follow-up period, although the possibility of bias cannot be excluded. Differential mortality associated with depression and pain seems unlikely because there were few deaths and no significant differences by pain or depression status after the analyses controlled for other health and socioeconomic differences. However, this relationship could be very different for a slightly older cohort, and such a group may require a different analysis. Because of the limited age range in our study, it is unclear whether the results generalize to elderly or younger populations. The assessment of mental health was also crude and not based on a clinical diagnosis, and measurement error on the CES-D scale could have created bias in these coefficient estimates.

Conclusions

This study showed that comorbid depression and pain are associated with serious effects on functioning and economic burdens that persist or increase in severity over time, at least among individuals approaching retirement age. Compared with the group with no pain or depression, all the groups with depression, pain, or both had greater decrements in outcomes. Groups tended to have greater decrements in outcomes as levels of pain increased, although no statistically significant differences were found between the groups with depression plus pain and their corresponding groups with pain alone. Depression with pain and pain alone were associated with greater decrements in outcomes than depression alone, even when the pain reported was mild or moderate.

The potential costs and impact associated with co-occurring depression and pain should be cause for concern because of the prevalence of these conditions and findings that individuals with depression and pain are more likely than those with depression alone to stay depressed or later develop reoccurring depression as they near retirement and less likely to receive specialty mental health care.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Mr. Emptage is affiliated with the department of health management and policy at the University of Michigan, 109 Observatory Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sturm is with RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California. Ms. Robinson is with the department of outcomes research at Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of one new limitation in activities of daily living among participants in the Health and Retirement Study, by baseline (1994) symptoms of pain and depression

Figure 2. Estimated total medical expenditures from 1994 to 2000 among participants in the Health and Retirement Study, by baseline (1994) symptoms of pain and depression

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 8,280 participants in the Health and Retirement Study, by baseline (1994) symptoms of pain and depressiona

a Percentages were weighted for the sampling design to provide nationally representative estimates.

|

Table 2. Logistic regression models of the outcomes of participants in the Health and Retirement Study, by baseline (1994) symptoms of pain and depressiona

a No depression or pain is the reference group for all analyses. Adjusted for baseline age, gender, race or ethnicity, number of chronic conditions, arthritis, number of years of education, employment status (except where this is the dependent variable), marriage or partner status, and annual household income

|

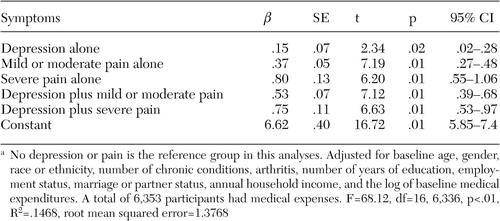

Table 3. Loglinear regression models of total medical expenditures from 1994 to 2000 for participants in the Health and Retirement Study, by baseline symptoms of pain and depressiona

a No depression or pain is the reference group in this analyses. Adjusted for baseline age, gender, race or ethnicity, number of chronic conditions, arthritis, number of years of education, employment status, marriage or partner status, annual household income, and the log of baseline medical expenditures. A total of 6,353 participants had medical expenses. F=68.12, df=16, 6,336, p<.01, R2=.1468, root mean squared error=1.3768

1. Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E: Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Annals of Internal Medicine 134:9 17–925, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, et al: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. New England Journal Medicine 341:1329–1335, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Von Korff M, Simon G: The relationship between pain and depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 30:101–108, 1996Google Scholar

4. Kroenke K, Price RK: Symptoms in the community: prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Archives of Internal Medicine 46:2474–2480, 1993Google Scholar

5. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al: Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Archives of Family Medicine 3:774–779, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF: Using chronic pain to predict depressive morbidity in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:39–47, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM, Dworkind M, et al: Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:734–741, 1993Link, Google Scholar

8. Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al: Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:2428–2434, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, et al: Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine 163:2433–2445, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hotopf M, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, et al: Temporal relationships between physical symptoms and psychiatric disorder: results from a national birth cohort. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:255–261, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Livingston G, Watkin V, Milne B, et al: Who becomes depressed? The Islington community study of older people. Journal of Affective Disorders 58:125–133, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mantyselka PT, Turunen JHO, Ahonen RS, et al: Chronic pain and poor self-rated health. JAMA 290:2435–2442, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bao Y, Sturm R, Croghan TW: How does chronic pain impact health care utilization by depressed individuals? A national study. Psychiatric Services 54:693–697, 2003Link, Google Scholar

14. Sherbourne CD, Sturm R, Wells KB: What outcomes matter to patients? Journal of General Internal Medicine 14:357–363, 1999Google Scholar

15. The Health and Retirement Survey: A Longitudinal Study of Health, Retirement, and Aging. National Institute on Aging Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2005. Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.eduGoogle Scholar

16. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Steffick DE: Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Report DR-005. Survey Research Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich, 2000Google Scholar

18. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Stata, Version 7.0. Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex, 2003Google Scholar

20. Duan N, Manning W, Morris C, et al: A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 1:115–126, 1983Google Scholar

21. Manning WG, Mullahy J: Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? Journal of Health Economics 20:461–494, 2001Google Scholar