Special Section on the GAF: Using the GAF as a National Mental Health Outcome Measure in the Department of Veterans Affairs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) were used to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), a single-item mental health status measure, as an outcome measure for large mental health care systems. METHODS: The sample consisted of VHA mental health patients who had at least two GAF scores 45 days apart in 2002 (N=283,754). First, to evaluate the discriminant validity of the GAF change measures, the authors examined the association of these measures with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Facility-level risk-adjusted measures of GAF change were then created in three different clinical samples at more than 130 VHA medical centers, adjusting for patients' sociodemographic characteristics and diagnoses. The internal consistency of the scale created by using these items and their consistency across medical centers over time was evaluated. RESULTS: The analysis supported the discriminant validity of the GAF-derived measures. As expected, veterans who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or Alzheimer's disease or who had service-connected disability ratings above 50 percent had lower baseline GAF scores and showed less improvement. The overall GAF performance measure had a high level of internal consistency (a standardized alpha of .85) and was highly consistent across facilities over time. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study provide preliminary empirical support for cautious use of a GAF-derived scale in monitoring changes in average facility-level outcomes over time. However, because of the potential for gaming of the measures and uncontrolled variation in the scale's administration across facilities, the scale should not be used to compare outcomes across facilities.

The U.S. mental health care system has undergone dramatic changes in recent years, involving major reductions in the availability of inpatient care, greater emphasis on outpatient care, and pressure to improve efficiency in both inpatient and outpatient domains (1,2,3,4,5,6). In response to these changes there has been growing concern about maintaining the quality and effectiveness of care and a recognition of the need for systematic monitoring of health system performance (7,8).

Although many mental health systems have used administrative data to monitor the structure and process of care (9), outcomes have received far less attention (10). Methods for assessing mental health outcomes are well developed for use in research, but they are costly to implement, especially on a large scale at multiple facilities (11,12,13).

Despite these impediments, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the Committee on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities as well as both public and private insurers require accredited programs to systematically monitor the outcomes of treatment (14,15,16,17), presumably because previous measures are an imperfect proxy for the ultimate goal of mental health services—improving mental health status and functioning.

In recognition of both the importance and potentially high cost of outcomes monitoring, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the Department of Veterans Affairs issued a policy directive in 1999 that all mental health inpatients be rated with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) at discharge and that outpatients be rated with the GAF at least once every 90 days during active treatment (18).

The GAF is a single-item rating with which a treating clinician evaluates the current global functional status of each patient on a scale of 1 to 100 with brief anchors at 10-point intervals; higher scores indicate better functioning. The VHA selected the GAF because it is inexpensive, is practical to administer, and has demonstrated potential to be used reliably (19,20,21,22). Moos and colleagues (4) recently demonstrated that GAF scores collected by VHA clinicians were significantly associated with current symptoms and functioning, although these scores did not predict future health status or costs. However, substantial concerns about the GAF have been expressed, because the scale uses one item to measure many different functional areas, it excludes physical impairment (23), and it has greater association with psychiatric symptoms than with functional abilities (24).

Although the GAF is a potentially informative and inexpensive outcome measure, there has been no examination of its use to monitor client outcomes at the facility level in a large health care system. In the study reported here we used national VHA GAF data from three fiscal years first to evaluate the scale's discriminant validity—that is, the degree to which patients' diagnoses and other characteristics corresponded as expected to patient-level GAF scores and GAF change scores. We then examined the strength of the interrelationship of three component measures that make up a facility-level performance scale—that is, the scale's internal consistency. These component measures represent facility-level GAF change in three distinct clinical subpopulations. Finally, we examined the temporal stability of these facility-level performance measures. More broadly, we sought to demonstrate a set of strategies for making use of individual-level health status data to assess facility-level performance.

Methods

Source of data

GAF ratings were obtained from a national file containing all GAF ratings made by VHA clinicians along with patient identifiers, an indicator of whether the rating was made at the end of an inpatient stay or during an episode of outpatient care, the date the rating was made, and a code documenting the specific facility at which the rating was made. GAF ratings were completed as treatment occurred rather than at the beginning of a client's treatment, because many VHA patients have been in and out of treatment for various periods. For outpatients, such an approach has the benefit of preventing clinicians from attempting to "game" the indicator, given that the clinician does not know which particular score will be used as the baseline and which as the follow-up score. Gaming is less preventable for the measures concerning discharged inpatients, because clinicians can potentially identify the baseline assessment, which occurs at discharge. However, it should be noted that the clinicians who make the outpatient GAF ratings are different from those who make the inpatient ratings, and they do not have access to the inpatient ratings.

Data on veterans' sociodemographic and diagnostic characteristics were obtained from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administrative workload files: the Patient Treatment File, the Encounter File, and the Outpatient Care File, which document all VA inpatient and outpatient treatment.

Sample

Our analytic sample consisted of three groups: patients who had at least one inpatient GAF rating and a later outpatient GAF rating, new outpatients who had at least two outpatient GAF ratings, and continuing outpatients who had at least two outpatient GAF ratings. For the inpatient or outpatient to be included in the sample, the second outpatient GAF rating in each case had to have been made at least 45 days after the initial rating. Such GAF data were available for 273,036 veterans who received outpatient services in 2002 and for 10,718 inpatients in 2002. The veterans for whom two GAF ratings were available represent 48.5 percent of all veterans who had two outpatient mental health stops 45 days apart and 22 percent of the inpatients who had at least one outpatient stop 45 days after their inpatient stop. The mean±SD baseline GAF score was 41.2±13.9 for inpatients and 53.5±11.5 for outpatients.

For comparison, we used samples of inpatients and outpatients from 2000 and 2001. GAF data were obtained for 14,626 veterans who received inpatient services in 2000 and 279,904 patients who received outpatient care as well as for 11,210 veterans who were inpatients in 2001 and 252,221 outpatients. The patients in our samples received services at more than 129 different VA medical centers (VAMCs).

From the original sample for each year, three subgroups of patients were identified: inpatients (those with a GAF rating at the end of an inpatient stay and a subsequent outpatient GAF rating), new outpatients (veterans receiving outpatient services in each fiscal year who did not have any outpatient stops in the last quarter of the previous fiscal year and thus are assumed to have begun a new episode of outpatient care), and continuing outpatients (those who had at least one outpatient visit in the last quarter of the previous year).

Measures

GAF change measure. We examined two GAF change measures, one reflecting short-term changes and the other reflecting longer-term changes. Short-term change was defined as the difference between the initial GAF rating and the last rating that occurred between 45 and 135 days later (the next quarterly rating). Long-term change was defined as the difference between the baseline GAF rating and the last GAF rating in the fiscal year that occurred at least six months later. Thus, although an individual patient could have either a short- or long-term GAF change score, or both, the short-term rating of necessity differs from the long-term rating.

Risk adjusters. Because patients being treated at different facilities are likely to differ on characteristics that may affect outcomes, such as age, gender, or diagnosis (25), outcomes must be risk-adjusted for these differences, as described in detail elsewhere (26).

Aggregated VAMC treatment outcome measure. Because the goal of performance assessment is to compare outcomes across facilities, three separate risk-adjusted facility-level outcome measures were created, reflecting short-term change among discharged inpatients, short-term change among new outpatients, and longer-term change among continuing outpatients. These three facility-level measures were then standardized and averaged to create a measure that represented the overall performance of each institution.

In developing this measure of overall site performance, we first created risk-adjusted facility-level versions of each of the three component outcomes measures. To do so, we used data from individual patients in multiple regression models to create risk-adjusted measures of the performance of each VAMC (25). In these analyses the patient-level measure of GAF change was the dependent variable. Independent variables include measures of veterans' sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses, and the baseline value of the GAF score along with N - 1 dichotomous variables representing each site, with the median site excluded as the reference condition. The coefficient on each dichotomous site variable in this model thus represents the difference in the GAF change score between that site and the excluded site (which has a score of 0, by definition), with sociodemographic and clinical factors controlled for. The variation explained by the inclusion of these risk adjusters (R2) was 44 percent for the inpatient GAF change model and 22 percent for the two outpatient models.

Using these methods, we created three risk-adjusted measures of effectiveness at the site level that reflected short-term risk-adjusted GAF change among discharged inpatients, short-term risk-adjusted GAF change among new outpatients, and long-term risk-adjusted GAF change among continuing outpatients. These three site-level measures were standardized with use of Z scores and were then averaged to create a measure representing the overall performance of each VAMC.

Analyses

SAS software system procedures (27,28,29) were used for all analyses. An examination of how representative the sample was—that is, how veterans in the GAF samples differed from those without complete GAF data—showed that the sample for whom ratings were available was representative of those who receive the most extensive services and who therefore are of greatest interest and concern (26).

Discriminant validity. Next we evaluated the discriminant validity of the GAF data. These analyses, conducted at the client level, examined six models: three that predicted baseline GAF scores and three that predicted GAF change scores. Each of these six models included all measures of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. We hypothesized that change scores would be most favorable among discharged inpatients and new outpatients and that both baseline and change scores would be superior among patients with less severe disorders, such as dysthymia, and worse among those with schizophrenia, with Alzheimer's disease, or who received VA compensation at a level above 50 percent.

Facility performance scale. We then analyzed the internal consistency of the overall VAMC-level GAF performance scale on the basis of the three risk-adjusted and standardized GAF measures. To do so, we estimated Cronbach's alpha for the three VAMC-level measures of effectiveness by using data from each of three years (fiscal years 2000 through 2002) and more than 129 VAMCs. We also examined the temporal stability of the three risk-adjusted measures (and the overall GAF performance scale) across the three years of data by examining the correlation of the 2000, 2001, and 2002 versions of these measures.

Results

Sample characteristics

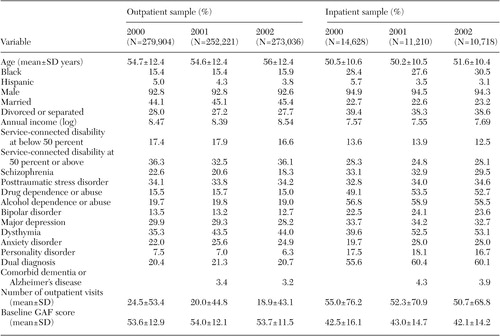

The characteristics of the outpatient and inpatient samples changed little over the study period, as can be seen in Table 1. As would be expected, individuals in the inpatient sample were more likely to have diagnoses of severe mental illness, higher disability ratings, and 20 percent lower baseline GAF ratings.

Discriminant validity

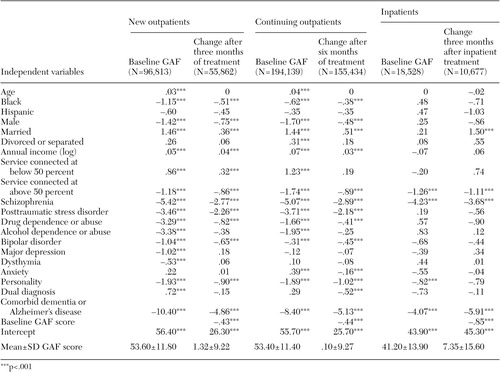

As hypothesized, indicators of more severe illnesses, such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, and bipolar disorder, and disability ratings of 50 percent or greater were associated with lower baseline scores and less improvement (Table 2). There were also a number of highly significant and negative associations between the diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder, drug abuse or dependence, and personality disorders and both the baseline GAF scores and GAF change measures (Table 2).

Furthermore, the mean baseline GAF score was 29 percent higher for the two groups of outpatients—both new and continuing—than for the group of inpatients. Taken together, these results provide support for the discriminant validity of the GAF measures.

Internal consistency and correlation between GAF items

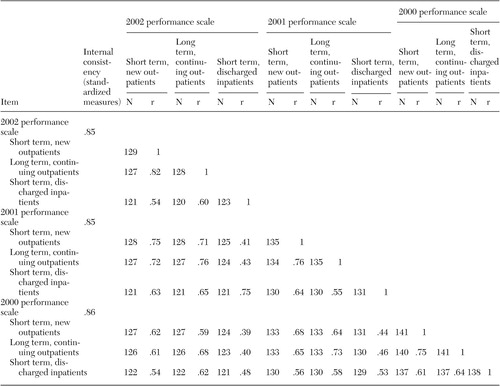

Table 3 presents the Cronbach's alphas for the GAF performance scale constructed with use of the three risk-adjusted and standardized VAMC-level GAF measures for each year. The values of .85 to .86 for the Cronbach's alphas across years indicate a high level of internal consistency of this scale and a high correspondence of our three measures between facilities.

The table also shows the strong intercorrelation of these three VAMC-level measures. The correlation between the two outpatient measures was between .75 and .82, and the inpatient measure was correlated with the two outpatient measures at between .54 and .65 in each year of the study. These correlations demonstrate that individual VAMCs have consistently higher or lower scores relative to other VAMCs across measures, even with quite different samples of patients.

The temporal stability of the three measures was reflected in the correlations of the individual measures across years, generally above .60 (Table 3). The three overall GAF performance scales created for each year were correlated at from .69 to .83 (all p<.001; N=129 to 135) (data not shown in Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study we are aware of to demonstrate an analytic strategy for the creation of a facility-level performance measurement from simple client outcomes data. Although there is an extensive literature on the assessment of mental health outcomes in research on specific interventions, few studies have examined outcomes in large health care systems on an ongoing basis. Although such assessments can be costly, the study reported here relied on a relatively inexpensive measure, the GAF, which was used to rate mental health status periodically on several hundreds of thousands of patients treated nationally in the VHA system over several years.

Although the ratings were made by untrained clinicians, without formal assessment of interrater reliability, the analyses of the relationship of baseline GAF score and changes in GAF scores showed encouraging discriminant validity. As expected, the greatest amount of improvement was found among discharged inpatients between the time of discharge and patients' first rating after their entry into outpatient care. Somewhat less improvement was found for new outpatients, and the least improvement was found for continuing outpatients. In addition, the lowest baseline scores and least improvement were observed among patients with schizophrenia or Alzheimer's disease, conditions that are typically considered to have poor prognoses, and among veterans with the highest disability ratings.

In addition to the evidence of discriminant validity noted above, we found high consistency in facility-level ratings across the three measures and across years, which suggests that the GAF data reported here reflect consistent characteristics of the medical centers that were being evaluated. The strong internal consistency of the overall GAF performance scale also encourages confidence in this measure as an indicator of a facility's performance.

However, despite these encouraging findings, given the possible gaming of the measures and variation across facilities in the scale's administration, we suggest that the scale is more appropriate for examining changes at a single facility over time than for comparing facilities. GAF change measurements could be gamed, because clinicians could identify which GAF score of discharged inpatients would be used as the baseline assessment.

Although outpatient raters could not tell which ratings would be used as a baseline measure and which as a follow-up measure, it is always possible that if the measures developed here were used to evaluate performance, innovative gaming techniques might be developed that have not been considered. It is also possible that differences in culture and rules across facilities may result in variation across facilities in the administration of the GAF score. Thus, because it is possible that variation across facilities in GAF change scores may reflect diverse confounding factors other than actual patient outcomes, the GAF scale developed here would be more appropriate for examining overall changes within a single facility but not for comparing facilities.

Several other limitations require comment. First, the GAF score remains a single value whose reliability and validity in this specific real-world setting has not been demonstrated, and several researchers have expressed substantial concerns about the GAF (23,24). However, it is notable that Moos and colleagues (4) found significant relationships between GAF ratings extracted from the same data file as the one used in this study and psychometrically sound measures.

Second, risk adjustment relied entirely on administrative data that do not include measures of clinical status or substance abuse.

Third, GAF data were available for an incomplete subgroup of all VHA patients, and there is evidence that this subgroup was significantly different from other patients who received VHA mental health services. However, the subgroup for whom data were available were those who received the most extensive services and who had the most severe illnesses, and therefore were of greatest interest and concern.

A fourth limitation is that because the discriminant validity analyses were based on a large sample and thus had substantial power, some statistically significant findings may not be clinically meaningful (30). There is no standard for determining how large a change in the GAF score is clinically meaningful. However, a study that compared clozapine and haloperidol showed that small differences in GAF scores (2.2 points) favoring clozapine paralleled significant differences in other accepted measures, such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (31). Thus small changes in GAF scores may be clinically meaningful.

Another possible limitation of the measures presented here is that the GAF change measures may have been biased by knowledge of patients' diagnoses and the treatment settings—that is, whether inpatient or outpatient. For instance, the GAF scores of patients with severe diagnoses or who have been recently discharged may be influenced by the clinician's awareness of that information.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated several strengths of a facility-level outcomes measure derived from the GAF and the possibility of using that measure to assess outcomes at individual facilities over time, even in the absence of formal training or reliability assessment of providers. However, in view of the concerns about the validity of the GAF score expressed by Moos and colleagues (4) and by others (23,24), further studies in other settings with more extensive validation are needed, and the results presented here should be considered preliminary and exploratory. Thus, although the GAF provides outcome data that go beyond readily available process measures, at very low cost, it should be used with caution and in combination with more objective process measures, such as readmission rates or timely access to outpatient care. Although both kinds of data are imperfect, we believe that they complement each other in constructive ways; however, it should be emphasized that the GAF cannot categorically differentiate unacceptable and acceptable facility performance. The GAF merely provides information about changes in average health status at the facility level. To the degree financially feasible, quality assurance systems for the GAF score—for example, training and testing for interrater reliability—should also be consistently implemented. Until such efforts are effectively implemented across the VHA system, the possibility of systemic rater bias (caused by such factors as gaming or differences between facilities in their culture and rules) precludes the use of the GAF developed here for comparisons across facilities.

The authors are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven, Connecticut, and with the department of psychiatry of Yale University in New Haven. Address correspondence to Dr. Greenberg at Northeast Program Evaluation Center, VAMC, West Haven, Connecticut 06515 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of veterans who participated in a study of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

|

Table 2. Discriminant validity of baseline and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) change scores in a sample of veterans during fiscal year 2002

|

Table 3. Internal consistency and correlation between items of the medical center-level Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) performance scale in a sample of veterans, 2000 to 2002 (all p<.001)

1. Chen S, Wagner TH, Barnett PG: The effect of reforms on spending for veterans' substance abuse treatment, 1993–1999. Health Affairs 20(4):169–175, 2001Google Scholar

2. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40–52, 1998Google Scholar

3. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Shifting to outpatient care? Mental health care use and costs under private insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1250–1257, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Moos RH, Nichol AC, Moos BS: Global Assessment of Functioning ratings and the allocation and outcomes of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 53:730–737, 2002Link, Google Scholar

5. Randel L, Pearson SD, Sabin JE, et al: How managed care can be ethical. Health Affairs 20(4):43–56, 2001Google Scholar

6. Yohanna D, Christopher NJ, Lyons JS, et al: Characteristics of short-stay admissions to a psychiatric inpatient service. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 25:337–345, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Scheid T, Greenley JR: Evaluations of Organizational Effectiveness in Mental Health Programs. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:403–426, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA: Defining quality of care. Social Science and Medicine 51:1611–1625, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Donabedian A: Exploration in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, vol I: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. Ann Arbor, Mich, Health Administration Press, 1980Google Scholar

10. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Quality measurement and accountability for substance abuse and mental health services in managed care organizations. Medical Care 40:1238–1248, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. American Psychiatric Association Task Force for the Handbook of Psychiatric Measures: Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

12. Sederer L, Dickey B: Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck R, Stolar M, Fontana A: Outcomes monitoring and the testing of new psychiatric treatments: work therapy in the treatment of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Health Services Research 35(1 pt 1):133–151, 2000Google Scholar

14. Eisen S: Clinical status: charting for outcomes in behavioral health. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 23:347–361, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Performance Indicators for Rehabilitation Programs. Version 1.1. Tucson, Ariz, Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission, 1998Google Scholar

16. Smith GR, Manderscheid RW, Flynn LM, et al: Principles for assessment of patient outcomes in mental health care. Psychiatric Services 48:1033–1036, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Young AS, Grusky O, Jordan D, et al: Routine outcome monitoring in a public mental health system: the impact of patients who leave care. Psychiatric Services 51:85–91, 2000Link, Google Scholar

18. Van Stone W, Henderson K, Moos RH, et al: Nationwide implementation of Global Assessment of Functioning as an indicator of patient severity and service outcomes, in Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Edited by First MB. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003Google Scholar

19. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring the overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Tracy K, Adler LA, Rotrosen J, et al: Interrater reliability issues in multicenter trials: I. theoretical concepts and operational procedures used in Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study #394. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 33:53–57, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rey JM, Starling J, Wever C, et al: Inter-rater reliability of Global Assessment of Functioning in a clinical setting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 36:787–792, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

23. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1148–1156, 1992Link, Google Scholar

24. Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unutzer J, et al: Evidence for limited validity of the revised Global Assessment of Functioning scale. Psychiatric Services 47:864–866, 1996Link, Google Scholar

25. Rosenheck RA, Cicchetti D: A mental health program report card: a multidimensional approach to performance monitoring in public sector programs. Community Mental Health Journal 34:85–106, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA: National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 2002 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2003 Available at www.nepec.orgGoogle Scholar

27. SAS/STAT User's Guide, version 6, 4th ed, vol 1: ACECLUS-FREQ. Carey, NC, SAS Institute, 1990Google Scholar

28. SAS/STAT User's Guide, version 6, 4th ed, vol 2: GLM-VARCOMP. Carey, NC, SAS Institute, 1990Google Scholar

29. SAS Procedures Guide, version 6, 3rd ed. Carey, NC, SAS Institute, 1990.Google Scholar

30. Drake RE, McHugo GJ: Large data sets can be dangerous! Psychiatric Services 54:133, 2003Google Scholar

31. Rosenheck RA, Cramer J, Xu W, et al: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 337:809–815, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar