Global Assessment of Functioning Ratings and the Allocation and Outcomes of Mental Health Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) is an integral part of the standard multiaxial psychiatric diagnostic system. The purpose of including the GAF in DSM-IV as a tool for axis V assessment is to enable clinicians to obtain information about global functioning to supplement existing data about symptoms and diagnoses and to help predict the allocation and outcomes of mental health treatment. The purpose of this study was to examine the value of the GAF as part of a systemwide program for monitoring the allocation and outcomes of mental health care services. METHODS: Clinicians used the GAF to assess global functioning among 9,854 patients with psychiatric or substance use disorders, or both, who were already participating in an outcomes monitoring program of the Department of Veterans Affairs. A longitudinal prospective follow-up design was used. RESULTS: Patients' clinical diagnoses and symptoms were stronger predictors of GAF ratings than was their social or occupational functioning. GAF-rated impairment was associated with the provision of inpatient or residential care and outpatient psychiatric care, but patients with greater levels of impairment did not receive more treatment. GAF ratings were only minimally associated with treatment outcomes. No robust associations were found between GAF ratings and outcomes as assessed by clinician interview or by patients' self-report at follow-up. CONCLUSIONS: Including GAF ratings in a program for predicting the allocation and outcomes of mental health care is of questionable value. Research is needed to determine whether systematic training and ongoing validity checks would enhance the contribution of the GAF in monitoring service use and outcomes.

In this era of accountability and managed care, there is growing emphasis on predicting the allocation and outcomes of mental health services. Assessment and evaluation systems that have been developed to make such predictions focus on characterizing patients in terms of both their symptoms and their level of functional impairment, assessing patients' need for treatment and providing guidelines for the allocation of services, and monitoring progress and outcomes (1,2).

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) is the standard method for representing a clinician's judgment of a patient's overall level of psychosocial functioning. As such, it is probably the single most widely used method for assessing impairment among patients with psychiatric or substance use disorders or both (3,4). The GAF requires a clinician to make an overall judgment about a patient's current psychological, social, and occupational functioning. In DSM-III-R, this rating is made on a scale from 1 to 90, with ratings of 1 to 10 indicating severe impairment and ratings of 81 to 90 indicating superior functioning (5); in DSM-IV, the rating is made on a scale from 1 to 100 (6).

The rationale behind the multiaxial psychiatric diagnostic system is that each axis should reflect a different piece of information about the patient. Axis V, which reflects global functioning and is assessed with the GAF, thus should supplement existing information about the patient's symptoms and diagnoses, which are covered by axis I and axis II. In addition, ratings of the patient's current level of functioning should be of value in predicting the allocation of mental health services and treatment outcomes (6,7,8). Both clinicians and researchers consider the GAF to be a key part of any outcomes assessment program (9,10). Moreover, according to DSM-IV (6), the information obtained through the GAF "is useful in planning treatment and measuring its impact and in predicting outcome."

As part of its participation in the Government Performance and Results Act, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented a nationwide system for evaluating the allocation and effectiveness of psychiatric and substance abuse services. Under this system, the VA mandated that clinicians use the GAF in the diagnostic assessment of all mental health patients. We report on the use of the GAF in a sample of patients who participated in this monitoring program.

Symptoms and functioning as predictors of GAF scores

Diagnoses and the severity of symptoms are predictably associated with clinicians' ratings of patients' global impairment. For example, patients who have more severe psychiatric disorders, especially psychoses and posttraumatic stress disorder, are rated as having a greater level of impairment than those who have less severe disorders (8,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). In addition, GAF ratings have been associated with clinician- and self-rated depression, suicidal ideation, and lack of self-esteem (18,19,20,21,22) as well as self-rated global distress (2,20), cognitive disorganization (3,23), schizophrenic symptoms (24), and suspiciousness and paranoid ideation (3).

GAF ratings of impairment are modestly associated with some indexes of social functioning, such as the extent of social networks and the need for support (8,25,26), and with residential instability, lack of employment, and poor work adjustment (14,27). In general, however, these relationships are relatively weak; GAF ratings tend to be more closely associated with diagnoses and psychiatric symptoms than with social and occupational functioning (16,19).

GAF scores as predictors of service allocation and outcomes

Patients with higher levels of global impairment have a higher likelihood of receiving inpatient or residential care and a longer duration of such care (28,29,30,31,32,33.) However, with the exception of Bogenschutz and Siegfried (34), who found no relationship between GAF scores and the use of outpatient mental health services, researchers have not focused on the association between GAF-rated impairment and the duration of mental health treatment or the allocation of services.

Several studies have identified associations between clinicians' ratings of patients' global functioning and improvement in patients' psychiatric and substance use problems during and after treatment (2,4,24,35,36,37,38,39). In general, these associations have been stronger than those between GAF ratings and social or occupational outcomes (14,21,33,40,41,42).

In an earlier study that used a different sample of patients with substance abuse, we found that GAF ratings obtained during treatment were only minimally associated with self-reported symptom outcomes and social or occupational outcomes (14). We sought to replicate and extend these findings by addressing three questions. First, when clinicians use the GAF to rate patients' global impairment, do they consider social and occupational functioning in addition to diagnoses and clinical symptoms? Second, how closely are GAF ratings associated with patients' receipt of mental health services—that is, do patients with greater levels of impairment receive more care? Third, how well does the GAF predict patients' symptom outcomes and outcomes related to social or occupational functioning? We also examined whether GAF ratings were more strongly associated with interview-based outcome measures than with self-reported outcome measures.

Methods

In addition to mandating that clinicians use the GAF to assess mental health patients, the VA mandated the use of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (43) for assessing all patients with a substance use disorder, including those with a comorbid psychiatric disorder, at entry into treatment and at a follow-up assessment six to 12 months later (44). The primary data were obtained between 1997 and 1999.

During the first phase of the outcomes monitoring program, clinicians at 148 VA facilities used the GAF to rate 9,854 patients who also received baseline and follow-up ASI assessments. The clinicians were experienced mental health professionals—primarily psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers—who made the GAF ratings in the context of regular clinical diagnostic interviews. The mean±SD interval between assessment with the GAF and follow-up administration of the ASI was 8.1±6.2 months.

Measures

Experienced clinicians administered the ASI during clinical interviews at baseline. We used items from the ASI to assess three symptom-related outcome criteria: psychiatric symptoms, based on the presence of any of six symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and hallucinations; substance use, based on whether the patient used alcohol or any of eight drugs, such as heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and barbiturates; and substance use problems, based on whether the patient experienced any problems as a result of using alcohol or drugs.

We also used the ASI to assess four social and occupational functioning variables: family or social problems, based on the presence of serious problems in getting along with family members; whether the patient had at least one close friend; legal problems, based on whether the patient was awaiting trial or was in jail; and whether the patient was employed (yes or no).

Of the 9,854 patients who were rated with the GAF and who received an ASI assessment from a clinician at baseline, 6,515 completed an ASI interview at follow-up, and 3,339 completed a self-reported ASI. The psychometric characteristics (Cronbach's alpha and corrected item-subscale correlations) of the interviewer-based and self-reported ASI scores were closely comparable (45).

Service episodes

To examine the association between GAF ratings and receipt of services, we identified an index episode of mental health care for each patient. Specifically, we used information from the VA inpatient and outpatient databases—the Patient Treatment File and the Outpatient Clinic File, respectively—to determine receipt of mental health and medical services during the index episode.

The beginning of the episode was defined as the first day of treatment after an interval of at least 30 days without treatment. The end of the episode was defined as the last day of treatment before an interval of at least 30 days without any treatment, or, for outpatients, by a new episode of inpatient care (46). The mean±SD duration of the index episode was 6.6±7 months.

We obtained information about specific services provided during the index episode: whether the patient received inpatient or residential care, and, if so, the number of days of care; whether the patient received outpatient mental health or medical care, and, if so, the number of visits for psychiatric, substance abuse, and medical services.

Analysis

Although GAF ratings are typically made on a 90-point scale, the rating criteria are described in nine broad categories (5), and many researchers have combined GAF scores into fewer categories (14,20,22,31,47,48,49). Accordingly, we classified patients by using five categories of GAF scores: 1 to 40, pervasive impairment; 41 to 50, serious impairment; 51 to 60, moderate impairment; 61 to 70, mild impairment; and 71 to 90, minimal impairment.

To examine whether the five groups of patients were differentiated by baseline diagnoses and clinical symptoms as well as social and occupational functioning, we used analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi square test for dichotomous variables. We then conducted multiple regression analyses to identify the extent to which patients' baseline diagnoses and symptoms were associated with clinicians' GAF ratings and whether patients' social or occupational functioning contributed independently to these ratings. Next, we used ANOVA for continuous variables and the chi square test for dichotomous variables to examine differences in the allocation of services between the five groups of patients. Finally, we calculated correlations between GAF ratings and outcomes. Subsequent analyses focused on the baseline values of the outcome variables as predictors of outcome and the additional contributions of GAF ratings to outcome predictions.

Results

For 1,175 patients, clinicians made two separate GAF ratings within seven days. Pearson's correlation was .80 between the two continuous 90-point GAF ratings and .79 between the two ratings examined by GAF category (p<.001 for both).

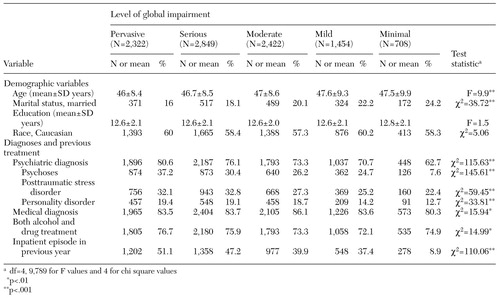

Diagnostic and basic demographic characteristics of patients in the five GAF-rated functioning categories are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in educational level or race were noted between the five groups. However, patients who were more impaired were slightly younger, were less likely to be married, and were more likely to have psychiatric diagnoses and to have received inpatient mental health care in the previous year.

The mean±SD age of the 9,854 patients was 46.8±8.7 years, and they had a mean of 12.6±2.1 years of education. Most patients (9,526, or 96.7 percent) were men. A total of 5,735 patients (58.8 percent) were Caucasian, 3,297 (33.8 percent) were African American, 499 (5.1 percent) were Hispanic, and 224 (2.3 percent) were from other racial or ethnic groups. Only 2,061 patients (21.1 percent) were currently married; 5,417 (55.4 percent) were separated or divorced, 341 (3.5 percent) were widowed, and 1,957 (20 percent) were single. (Information about race was not available for 99 patients, and information about marital status was not available for 78.)

Most patients (7,183, or 72.9 percent) had both a psychiatric and a substance use diagnosis; 4,847 patients (50.2 percent) had two or more psychiatric diagnoses. A total of 2,875 patients (29.2 percent) had a psychotic disorder, 2,896 (29.4 percent) had posttraumatic stress disorder, 5,445 (55.3 percent) had a depressive or anxiety disorder, 1,763 (17.9 percent) had a personality disorder, and 1,601 (16.3 percent) had other psychiatric disorders.

Determinants of GAF ratings

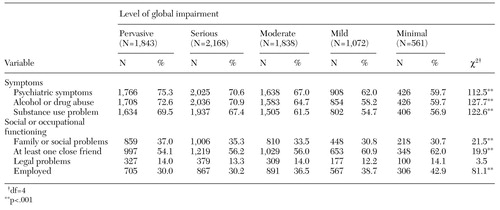

Data on the patients' symptoms and social and occupational functioning at baseline are presented in Table 2. Patients with greater levels of impairment were more likely to have severe psychiatric symptoms, to consume alcohol or drugs, and to have substance use problems, a finding that is consistent with the differences in diagnoses between patients in the five GAF categories. Differences between groups were also found in indexes of social and occupational functioning: patients with higher levels of impairment were more likely to have family or social problems and less likely to have at least one close friend or to be employed.

We conducted multiple regression analysis to identify the best independent predictors of GAF ratings. When entered first in the regressions, the social or occupational functioning indexes accounted for only 1 percent of the variance in GAF ratings. Patients' psychiatric diagnoses, previous inpatient care, psychiatric symptoms, and substance use and substance-related problems were each significantly associated with higher levels of global impairment. After these variables were entered, employment status was the only social or occupational index that independently predicted global functioning, and it accounted for less than 1 percent of the variance in clinicians' GAF ratings. The findings were essentially the same for the prediction of continuous as opposed to categorized GAF ratings.

GAF ratings and receipt of services

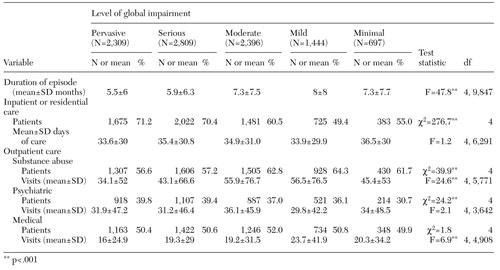

Data on receipt of services during the index episode by patients in the five GAF categories are presented in Table 3. Patients who were rated as having more serious or pervasive impairment had shorter episodes of care than patients with less impairment. Patients with greater impairment were more likely to have received inpatient or residential care. However, more than 50 percent of the patients with mild or minimal impairment received such care. Moreover, patients with lower levels of impairment received as much inpatient or residential care as those with higher levels.

Many of the patients received intensive outpatient care during the follow-up period and thus had several visits during each week of treatment. Patients who were more impaired were less likely to have received outpatient substance abuse care, and they received somewhat less of this type of care than those who were less impaired. Patients with greater impairment were somewhat more likely to have received outpatient psychiatric care but not to have received more psychiatric care in general. Outpatient medical care did not substitute for mental health care: patients with greater levels of impairment were no more likely than less impaired patients to have received outpatient medical care—in fact, they received somewhat less medical care.

GAF ratings and treatment outcomes

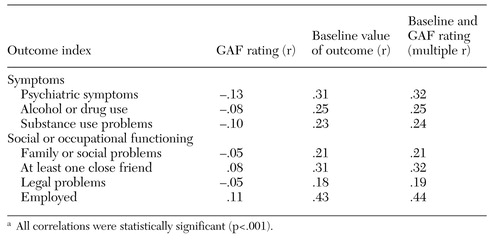

Next, we examined whether GAF ratings were associated with treatment outcomes. As the correlations in the first column of Table 4 show, GAF ratings were modestly related to symptom outcomes: patients with lower levels of impairment had fewer psychiatric symptoms and were less likely to have used alcohol or drugs or to have substance use problems at follow-up. GAF ratings also were related to social or occupational outcomes. Patients with lower levels of impairment were more likely to have at least one close friend or to be employed and were slightly less likely to have family, social, or legal problems. However, on average these correlations accounted for only about 1 percent of the variance in outcomes.

Each of the seven baseline variables predicted the equivalent outcome criterion—that is, psychiatric symptoms at baseline predicted psychiatric symptoms at follow-up—better than the GAF rating did, as column 2 of Table 4 shows. After the baseline value of the outcome variable was controlled for, GAF ratings made only a small contribution to each of the outcome criteria, as column 3 of Table 4 shows. We obtained essentially identical findings when we used continuous GAF scores rather than the five categories of GAF scores.

We thought that the GAF ratings might be better predictors of outcomes as assessed by clinicians' interviews than outcomes as assessed by patients' self-reports. Accordingly, we calculated correlations and multiple correlations—again, controlling for the baseline value of the outcome criterion—between GAF ratings and the seven outcome variables for the 6,515 patients who were interviewed and separately for the 3,339 who responded to a self-report inventory at follow-up. Contrary to our hypothesis, the associations observed at follow-up between GAF scores and outcomes as assessed by interview (average r=.08, average increment in r=.01) were no stronger than the associations between GAF scores and outcomes as assessed by self-report (average r=.10, average increment in r=.01).

Discussion and conclusions

We found strong agreement between clinicians in their routine ratings of patients' global impairment. In fact, the level of agreement was somewhat higher than that found in other studies (37,50,51). Nevertheless, the findings raise questions about the value of the GAF as an integral part of an outcomes monitoring system.

In DSM-IV, ratings of global functioning are included as a means of obtaining estimates of impairment to supplement existing information about a patient's diagnosis and severity of symptoms. However, in this study, clinicians' ratings of global impairment were more closely associated with patients' diagnoses, previous treatment, and severity of symptoms than with their social or occupational functioning. Patients with psychiatric diagnoses, psychoses, or a recent inpatient episode were rated as having greater impairment, as were patients who reported more psychiatric symptoms or substance use problems, or both. Once these clinical and symptom-related factors were considered, indexes of social and occupational functioning made only a negligible contribution to the GAF ratings.

These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies, which have shown moderately robust associations between symptoms and GAF ratings (18,20,21,22). Our findings and the results of these studies indicate that GAF ratings provide little or no information about social or occupational functioning that is independent of clinicians' judgments about diagnoses and the severity of symptoms (12,17,27).

With the exception of the provision of inpatient or residential and outpatient psychiatric care, we found either that ratings of global impairment were not associated with the allocation of services or that patients with greater impairment received fewer services. Moreover, we found little or no relationship between GAF ratings and either symptom outcomes or social or occupational outcomes. This result was the same when we used continuous GAF scores or the five categories of GAF scores.

In a previous study (14), we identified only minimal associations between clinicians' ratings of patients' current level of functioning and patients' self-rated symptoms and functioning at follow-up. We have replicated this finding and extended it to encompass treatment outcome as assessed by clinicians' interviews. In conjunction with the lack of previous positive findings that link GAF ratings to outcomes (28,52,53,54), these findings cast doubt on the value of including GAF ratings as predictors of treatment outcome in an outcomes monitoring system. Although intuitively appealing, a brief unidimensional rating of global functioning cannot capture changes in psychological, social, and occupational functioning that are only moderately interrelated at best (14,55,56).

This study had strengths and limitations. The GAF ratings were highly reliable, and there was some evidence of their validity, because patients with psychiatric diagnoses, psychoses, recent inpatient care, current inpatient or residential care, and more psychiatric symptoms and substance use problems were likely to be rated as being more impaired. However, the findings must be interpreted in the context of a lack of more definitive information about the validity of the GAF ratings—for example, through a validity check on vignettes of patients with known levels of impairment or through experts' ratings of a subset of patients.

One potential threat to the validity of the findings is that clinicians may have underrated patients' impairment, as suggested by the fact that about 50 percent of patients who were rated as mildly or minimally impaired had received some inpatient or residential care. This apparently anomalous finding may partly reflect two aspects of the clinical care of substance abuse patients. First, a large percentage of these patients receive a brief course of inpatient detoxification at the beginning of an extended episode of care. Second, many of them, including those who are employed and do not have severe functional impairment, receive some care in a protected and substance-free residential milieu. In addition, many of the patients with dual diagnoses had axis II diagnoses (primarily personality disorders), which often are consistent with only mild or moderate impairment in global functioning as rated by the GAF. Finally, decisions about patient placement often are made on the basis of factors other than patients' global impairment, such as the availability of beds and the level of support available to the patient in the community and from family members.

Overall, the findings have ecological validity in that they reflect the use of the GAF in actual practice as part of a standard clinical diagnostic interview in one nationwide system of care. They show that when the GAF is used without regular training or validity checks—which is probably the typical application in most clinical settings—it is problematic as a predictor of service allocation or treatment outcome. The findings also are consistent with a substantive body of literature on the GAF that has been amassed over the past 25 years. Nevertheless, a definitive conclusion about whether the GAF can be more validly implemented under more controlled conditions in a naturalistic clinical situation must await further research.

Further studies are needed to determine whether more extensive training and use of experts' ratings as validity criteria can enhance the value of the GAF as a predictor of treatment allocation and outcome. Future studies could also examine whether the GAF helps clinicians communicate more effectively about patients' impairment and whether comparisons of initial and follow-up GAF scores could be used to index program effectiveness. Finally, comparative studies of the GAF and alternative assessment procedures (6,15,57,58,59,60) should help identify clinically valid measures that tap patients' psychosocial functioning in a way that builds on existing information about their diagnoses and symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Strategic Healthcare Group and Office of Research and Development (Health Services Research and Development Service) and by grant AA-12718 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The work was conducted, in part, under the auspices of the Substance Abuse Module of the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Belle Federman, Ph.D., and Dori Lange, M.A., helped to obtain information from the VA utilization databases on patients' index episodes and prior care. The authors thank Penny Brennan, Ph.D., Ruth Cronkite, Ph.D., John Finney, Ph.D., Keith Humphreys, Ph.D., Paige Ouimette, Ph.D., Jeanne Schaefer, Ph.D., Kathleen Schutte, Ph.D., and Christine Timko, Ph.D., for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Health Care Evaluation and the Program Evaluation and Resource Center of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. Send correspondence to Rudolf H. Moos, Ph.D., at the Center for Health Care Evaluation (152-MPD), VA Health Care System, 795 Willow Road, Menlo Park, California 94025 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of 9,854 patients with psychiatric or substance use disorders, categorized by level of global impairment

|

Table 2. Symptoms and social and occupational functioning at baseline among 9,854 patients with psychiatric or substance use disorders, categorized by level of global impairment

|

Table 3. Receipt of services during the index episode by 9,854 patients with psychiatric or substance use disorders, categorized by level of global impairment

|

Table 4. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ratings as predictors of symptom outcomes and social or occupational outcomes among 9,854 patients with psychiatric or substance use disordersa

a All correlations were statistically significant (p<001).

1. Carise D, McLellan AT, Gifford LS, et al: Developing a national addiction treatment information system: an introduction to the drug evaluation network system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 17:67-77, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Farrell AD: Evaluation of Computerized Assessment System for Psychotherapy Evaluation and Research (CASPER) as a measure of treatment effectiveness in an outpatient training clinic. Psychological Assessment 11:345-358, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Piersma HL, Boes JL: The GAF and psychiatric outcome: a descriptive report. Community Mental Health Journal 33:35-40, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

7. Bodlund O, Kullgren G, Ekselius L, et al: Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale: evaluation of a self-report version. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:342-347, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Phelan M, Wykes T, Goldman H: Global function scales. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:205-211, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Moriearty P, Bogdanich R, Dexter N, et al: Incorporating results of a provider attitudes survey in development of an assessment program. American Journal of Medical Quality 14:178-184, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Shea T: Core Battery Conference: Assessment of Change in Personality Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1997Google Scholar

11. Alaja R, Tienari P, Seppa K, et al: Patterns of comorbidity in relation to functioning (GAF) among general hospital psychiatric referrals: European Consultation-Liaison Workgroup. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 99:135-140, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Brekke JS: An examination of the relationships among three outcome scales in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:162-167, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Coffey M, Jones S, Thornicroft G: A brief mental health outcome scale: relationships between scale scores and diagnostic/sociodemographic variables in the long-term mentally ill. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 3:89-93, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Moos RH, McCoy L, Moos BS: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ratings: determinants and role as predictors of one-year treatment outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56:449-461, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Robert P, Aubin V, Dumarcet M, et al: Effect of symptoms on the assessment of social functioning: comparison between axis V of DSM III-R and the Psychosocial Aptitude Rating Scale. European Psychiatry 6:67-71, 1991Google Scholar

16. Skodol AE, Link BG, Shrout PE, et al: The revision of axis V in DSM-III-R: should symptoms have been included? American Journal of Psychiatry 145:825-829, 1988Google Scholar

17. Skodol AE, Link BG, Shrout PE, et al: Toward construct validity for DSM-III axis V. Psychiatry Research 24:13-23, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Coulehan J, Schulberg H, Block M, et al: Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Archives of Internal Medicine 157:1113-1120, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Faravelli C, Servi P, Arends JA, et al: Number of symptoms, quantification, and qualification of depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry 37:307-315, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hall RCW: Global Assessment of Functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics 36:267-275, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WC, et al: Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:419-426, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Van Gastel A, Schotte C, Maes M: The prediction of suicidal intent in depressed patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 96:254-259, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Meltzer HY, Thompson PA, Myung AL, et al: Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 14:27S-33S, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Goldman M, Dequardo JR, Tandon R, et al: Symptom correlates of global measures of severity in schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry 40:458-461, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, et al: A brief mental health outcome scale: reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). British Journal of Psychiatry 166:654-659, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Westermeyer J, Neider J: Social networks and psychopathology among substance abusers. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1265-1269, 1988Link, Google Scholar

27. Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unutzer J, et al: Evidence for limited validity of the revised Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Psychiatric Services 47:864-866, 1996Link, Google Scholar

28. Dufton BD, Siddique CM: Measures in the day hospital: I. the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. International Journal of Partial Hospitalization 8:41-49, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gordon RE, Gordon KK: Relating axes IV and V of DSM-III to clinical severity of psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 32:423-424, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Kennedy CC, Madra P, Reddon JR: Assessing treatment outcome in psychogeriatric inpatients: the utility of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Clinical Gerontologist 20:3-11, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Rabinowitz J, Modai I, Inbar-Saban N: Understanding who improves after psychiatric hospitalization. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:152-158, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, et al: Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome study. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1443-1448, 1987Link, Google Scholar

33. Vetter P, Koller O: Clinical and psychosocial variables in different diagnostic groups: their interrelationships and value as predictors of course and outcome during a 14-year follow-up. Psychopathology 29:159-168, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Bogenschutz MP, Siegfried SL: Factors affecting engagement of dual diagnosis patients in outpatient treatment. Psychiatric Services 49:1350-1352, 1998Link, Google Scholar

35. Ezquiaga E, Garcia A, Bravo F, et al: Factors associated with outcome in major depression: a 6-month prospective study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:552-557, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Furukawa T, Awaji R, Nakazato H, et al: Predictive validity of subtypes of chronic affective disorders derived by cluster analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 91:379-385, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Howes JL, Haworth H, Reynolds P, et al: Outcome evaluation of a short-term mental health day treatment program. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:502-508, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1771-1776, 1994Link, Google Scholar

39. Walton SA, Berk M, Brook S: Superiority of lithium over verapamil in mania: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:543-546, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Rosenheck R, Seibyl CL: Effectiveness of treatment elements in a residential-work therapy program for veterans with severe substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 48:928-935, 1997Link, Google Scholar

41. Mellsop G, Peace K, Fernando T: Pre-admission adaptive functioning as a measure of prognosis in psychiatric inpatients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 21:539-544, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Beiser M, Fleming JAE, Fleming MB, et al: Refining the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:695-700, 1988Link, Google Scholar

43. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199-213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Moos R, Finney J, Federman E, et al: Specialty mental health care improves patients' outcomes: findings from a nationwide program to monitor the quality of care for patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:704-713, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Rosen C, Henson B, Finney J, et al: Consistency of self-report and interview-based Addiction Severity Index composite scores. Addiction 95:419-425, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Moos R, Federman B, Finney JW, et al: Outcomes Monitoring for Patients With Substance Use Disorders: II. Cohort I Patients' 6-12 Month Treatment Outcomes. Palo Alto, Calif, Program Evaluation and Resource Center and HSR&D Center for Health Care Evaluation, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1999Google Scholar

47. Mezzich JE, Fabrega H, Coffman GA: Multiaxial characterization of depressive patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175:339-346, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Schrader G, Gordon M, Harcourt R: The usefulness of DSM-III axis IV and axis V assessments. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:904-907, 1986Link, Google Scholar

49. Thompson JW, Burns BJ, Goldman HH, et al: Initial level of care and clinical status in a managed mental health program. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:599-603, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

50. Fernando T, Mellsop G, Nelson K, et al: The reliability of axis V of DSM-III. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:752-755, 1986Link, Google Scholar

51. Loevdahl H, Friis S: Routine evaluation of mental health: reliable information or worthless "guesstimates"? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:125-128, 1996Google Scholar

52. Piersma HL, Boes JL: Agreement between patient self-report and clinician rating: concurrence between the BSI and the GAF among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 51:153-157, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Sullivan CW, Grubea JM: Who does well in a day treatment program? Following patients through 6 months of treatment. International Journal of Partial Hospitalization 7:101-110, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

54. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1148-1156, 1992Link, Google Scholar

55. Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, Link B, et al: Social functioning of psychiatric patients in contrast with community cases in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:1174-1182, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: Prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:159-163, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Patterson DA, Lee M: Field trial of the Global Assessment of Functioning scale-modified. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1386-1388, 1995Link, Google Scholar

58. Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr: Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1992Google Scholar

59. Johnston M, Pollard B: Consequences of disease: testing the WHO International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (ICIDH) model. Social Science and Medicine 53:1261-1273, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Sullivan G, Dumenci L, Burnam A, et al: Validation of the Brief Instrumental Functioning Scale in a homeless population. Psychiatric Services 52:1097-1099, 2001Link, Google Scholar