Housing Preferences of Homeless Veterans With Dual Diagnoses

Abstract

Previous research indicates that most homeless persons with mental illness prefer independent living, while most clinicians recommend group housing. This study compared residential preferences of 141 homeless veterans with dual diagnoses with those of 62 homeless nonveterans with dual diagnoses. Clinicians rated both groups while they were in transitional shelters before they were placed in housing. Both samples strongly rejected group home living, but a majority of nonveterans desired staff support. Clinicians recommended staffed group homes for most veterans and nonveterans. This survey underscores the disjuncture between consumers' and clinicians' preferences as well as the need to provide a range of housing options to accommodate varied preferences.

Consumer choice is frequently recommended as the most appropriate basis of housing placement decisions for persons with severe and persistent mental illness, but previous research indicates that these choices vary between groups and often diverge from clinicians' recommendations (1).

Between 50 and 90 percent of mental health service consumers choose independent living over staffed group homes (2,3,4,5), but that varies with the type of group home (2,6). In one study of 80 consumers, nearly two-thirds preferred living with family members or roommates of one's choice, but just 8 percent wanted to live with other mental health consumers (7). Another study of 118 homeless persons with mental illness found that 92 (78 percent) preferred living with two to three persons over living with a larger group (4).

Consumers of mental health services are more willing to consider staff support than group living. Support from visiting staff is accepted, even desired, by between two-thirds and three-quarters of consumers (4,5,7,8). A study of 118 homeless consumers found that about half preferred full- or part-time staff and just a third rejected staff help for anything but the most difficult problems (4).

Clinicians' housing recommendations differ from consumers' housing preferences. Clinicians recommend some type of supported group living for between 60 percent and 80 percent of consumers (3,7), and those whom they recommend for independent living are not themselves more likely to prefer independent living (9).

We determined the housing preferences of a sample of homeless veterans with mental health and substance use problems and compared these preferences with both clinicians' recommendations and with the housing preferences of a sample of homeless nonveterans with dual diagnoses.

Methods

Data on housing preferences were collected from the records of standardized interviews with 141 homeless veterans with mental health and substance use problems who were referred to the Bedford addictions housing team at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital between September 2001 and August 2002. The hospital provides transitional residences and employment for homeless veterans, many of whom are bused daily from a homeless veterans' shelter in downtown Boston. The Bedford team was a five-person interdisciplinary case management group that offered veterans help with health problems and with acquisition and maintenance of community-based housing. Program eligibility was evaluated with the Addiction Severity Index scales of alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and psychiatric symptoms. The hospital institutional review board approved our retrospective analysis of deidentified data on program clients.

The 62 male substance abusers with chronic mental illness who participated in the Boston McKinney Project served as the comparison sample (4). These persons were assessed in 1990 to 1991 while they were staying in transitional shelters for homeless persons with mental illnesses. The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV was used to identify substance abuse and mental illness.

The sample was composed of 141 male veterans with a median age of 47. One-hundred-twenty-one (86 percent) were white. The comparison sample included only males, 39 (62 percent) of whom were white. The median age was 37. Neither race nor age were associated with the McKinney sample's residential preferences (4).

Residential preferences and history of the veterans were assessed on first referral to the Bedford team's program, and case managers subsequently rated the support needs of about half the veterans. The Bedford team veteran assessment used the Boston McKinney Project's residential preference and clinician recommendation instruments, after some modifications (4,9). The instruments are available on request from the first author. Veterans who initially indicated that they were more comfortable with getting help with finding housing and were less interested in living alone subsequently received more housing search help, which provided construct validation for the residential preferences questions. The inter-item reliability—Cronbach's alpha—of the complete veteran preferences and clinician recommendation indexes exceeded .8.

Results

Although 66 veterans (68 percent) rated themselves as very satisfied or satisfied with their current living situation—a homeless shelter or a transitional shelter at the medical center for all but six respondents—72 (78 percent) said that they would prefer to live alone rather than with others. It made little difference whether residents ran the group housing or whether there were only one or two others in the house. Preferences for staffing were more varied. Eighteen (19 percent) preferred to live with full-time staff, and 25 (28 percent) preferred a place run by staff rather than one run by residents, such as an Oxford-type residence or a Fairweather Lodge. Twenty-six (29 percent) had no preference between these alternatives. Seventy-four (79 percent) said that they liked having help with things they have a hard time managing by themselves.

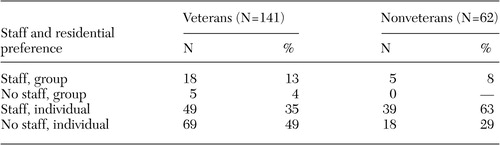

Of the veterans who did not reject the possibility of living with others, most favored living in a traditional staffed group home rather than in an unstaffed, resident-run group home (Table 1). Half the veterans sought to live independently without staff, and about a third sought independent living with staff support. The rejection of group living is comparable to findings in the comparison sample, but the nonveterans were more willing to accept staff support if they lived alone (χ2=14.8, df=6, p<.05).

Clinicians' housing recommendations differed markedly from the housing preferences of both client groups. Independent living was recommended for 14 (26 percent) of the veterans and for 18 (16 percent) of the nonveterans. In both samples, clinicians' recommendations were not associated with the housing preferences of the consumers (9).

Discussion

Most of the homeless veterans with dual diagnoses in this study preferred to live alone, even though many had moved into a transitional shelter at the time of the survey. They were also less interested in staff support than the nonveteran homeless comparison group. Some veterans indicated an interest in resident-run housing but only in response to a question that did not offer independent living. In both samples of homeless persons with dual diagnoses, the desire for independent living was markedly inconsistent with clinician recommendations. These discrepancies indicate the importance of assessing housing preferences before formulating housing placement policies rather than relying on previous research about other homeless subgroups or simply following clinicians' recommendations.

These discrepancies indicate the importance of assessing housing preferences before formulating housing placement policies rather than relying on previous research about other homeless subgroups or simply following clinicians' recommendations. Nonetheless, confidence in our findings must be tempered due to the limitation of our veteran sample to individuals referred for treatment at one medical center in one year. In addition, the omission in our veteran sample of measures of characteristics related to preferences such as perceived functional abilities and social supports precludes explanation of the veteran-nonveteran differences (4).

Conclusions

The desire of most homeless consumers with dual diagnoses for independent living was tempered by interest in staff support, while the resident-run models known as Oxford Housing and Fairweather Lodges had little appeal. For many consumers, supported housing—living independently with on-demand staff support—seemed to be the preferred model, but a significant number abjured all staff support. We urge further research with larger representative samples in order to explain this variation in preferences, with specific controls on need for and availability of support services and for satisfaction with previous service experiences that may shape current preferences (10). We also urge researchers to abjure conceptual and measurement approaches that assume a simple polarity of housing preferences and encourage them to systematically investigate the bases of the persistent discrepancy between clinicians' and consumers' housing preferences.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Veterans Administration New Clinical Program Initiative, which received funds from The Veterans Millennium Health Care and Benefits Act, P.L. 106-117, Section 101, (November 1999) and to Jillian Doucette for research assistance.

Dr. Schutt is affiliated with the department of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Boston, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, Massachusetts 02125 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Weinstein is affiliated with the graduate program in counseling psychology at Assumption University in Bangkok, Thailand. Dr. Penk is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Texas A & M University System College of Medicine in Temple, Texas.

|

Table 1. Residential preferences of homeless veterans and homeless nonveterans in a comparison sample

1. Carling PJ: Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:439–449, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Goering P, Paduchak D, Durbin J: Housing homeless women: a consumer preference study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 4:790–794, 1990Google Scholar

3. Holley HL, Hodges P, Jeffers B: Moving psychiatric patients from hospital to community: views of patients, providers, and families. Psychiatric Services 49:513–517, 1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM: Comparison of clinicians' housing recommendations and preferences of homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:381–386, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys of mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450–455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Friedrich RM, Hollingsworth B, Hradek E, et al: Family and client perspectives on alternative residential settings for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:509–514, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Minsky S, Riesser GG, Duffy M: The eye of the beholder: housing preferences of inpatients and their treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:173–176, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, et al: Housing accommodation preferences of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 47:628–632, 1996Link, Google Scholar

9. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK: Comparison of clinicians' housing recommendations and preferences of homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:413–415, 1996Link, Google Scholar

10. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM: The contingent rationality of housing preferences: homeless mentally ill persons' housing choices before and after housing experience. Research in Community and Mental Health 11:131–156, 2000.Crossref, Google Scholar