Family and Client Perspectives on Alternative Residential Settings for Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The housing preferences of persons with severe mental illness living in three types of community residences were examined, as were their perceptions of problems in these settings and the relationships between clients' and family members' housing preferences and perceptions of problems. METHODS: A closed-ended questionnaire was developed to gather demographic and diagnostic data and information about housing preferences and seven categories of service-related problems. It was completed by clients who lived in group settings with 24-hour on-site staff, in supported housing with on-site visits by staff, and in homes or apartments with no on-site professional services. Questionnaires were returned by 129 family members and 180 clients. RESULTS: Clients who lived in group settings were significantly more likely to be older, less educated, unemployed, and diagnosed as having schizophrenia than clients in other settings. Although a larger proportion of family members than clients preferred housing with more support, for both families and clients a statistically significant association was found between current and preferred residence. A strong and significant correlation was found between clients' and family members' perceptions of problems, which included stress on the family and clients' social isolation and relapse to illness. For clients who lived independently, a significantly greater proportion of both clients and families reported that social isolation was a problem. CONCLUSIONS: Although supported housing works well for some individuals, a continued need exists for an array of housing with varying levels of structure. The results suggest that clients and families identify the same problems as priorities.

As a result of deinstitutionalization, treatment of persons with severe mental illness has been shifted from hospitals to community-based systems of care. However, the comprehensive array of services and housing needed to help those with severe mental illness function at an optimal level within the community has not been developed in most jurisdictions. Many communities are ill equipped to meet clients' basic needs for shelter, food, and psychiatric care (1). Lack of adequate community services has resulted in an increase in homelessness (2), jailed mentally ill persons (3), and severe stress for families (4,5,6).

In response to the challenges of community care, state and local mental health systems are moving toward supported housing and away from a residential continuum of care. According to Nagy (7), the supported housing approach has been used as a strategy for "decongregating" traditional residential programs. More specifically, the shift is toward homes, not residential treatment settings; choices, not placement; physical and social integration, not segregated and congregate grouping by disability; and individualized flexible services and support, not standardized levels of service (8). This approach has been influenced by recent studies of consumers' preferences in the areas of housing and support, which show that a majority of consumers of mental health services prefer to live in their own apartment or home and not in residential mental health programs or facilities (9).

Because of national and state policy shifts toward supported housing, this approach has been replicated throughout the United States (7). However, some family members and professionals have expressed concern that those who are the most ill require a greater level of support and structure than independent living provides (10,11).

Lamb (12,13) describes structure as the missing ingredient in community care and states that no need is more important or varies more widely than the degree of structure clients receive in their living situation. Structure is provided by maintaining a high staff-to-patient ratio and by staff's dispensing medications and offering therapeutic activities throughout the day. Belcher and DeForge (14) point out that one of the most glaring problems arising as a result of dismantling the state hospitals is that people who need structured care are often without a place to receive treatment.

Dewees and associates (15) examined the level of community integration achieved by patients discharged from the state hospital into the community in compliance with a regionalization policy in Vermont. Integration and normalization did not occur for most clients, although they were the goals of the policy. Instead isolation, separation, stigma-related loneliness, and pervasive hard times were the dominant themes. The authors concluded that this particular population has greater need for supports afforded by supervised housing.

Few studies have examined the relationship between the problems clients experience and the amount of support or structure within settings, particularly since the advent of supported housing. An exception is a study by Lehman and associates (16) that explored differences in quality-of-life outcomes for persons with severe mental illness in four residential settings: a state hospital, large residential facilities, small group homes, and supervised apartments.

Although family members are primary caretakers for many severely mentally ill clients and often suffer from unending stress in that role, their viewpoints on housing have rarely been sought. The few studies that have examined family perspectives have demonstrated that families are about equally divided in their preferences for independent living and group settings (17,18). When client and family perspectives on housing issues have been compared, family members often prefer congregate living situations and more staff support than consumers want (19).

Because development of adequate housing is a major policy issue, knowing the preferences of both clients and family members is important in order to develop a housing strategy that works (19). Furthermore, the well-being of persons with severe mental illness in different community settings remains poorly understood. Assessing the impact of varying levels of structure on functioning of the client and the family is essential in planning community care.

The purpose of this study, which used a cross-sectional survey design, was to examine the housing preferences and current problems of persons with severe mental illness living in three types of community residences: group settings with 24-hour on-site staff, supported housing with on-site staff visits, and apartments or homes with no professional services within the residence. Family members' housing preferences and the relationships between clients' and family members' perceptions of housing needs and problems within these settings were also investigated.

Methods

Instrument

A closed-ended questionnaire, developed by the authors, was used to gather data concerning demographic and illness characteristics, housing preferences, and service-related problems. Problems were assessed with a 30-item checklist; clients and families were asked to identify problems experienced in the current living arrangement by checking yes if the item was a problem or no if it was not. Seven problem areas were assessed: interpersonal concerns, treatment issues, problems with daily living, finance and work issues, neglect of general health, problems associated with the physical setting, and safety.

Extensive pilot testing of the instrument was conducted with family members and clients in hospital and community settings before the study began. Two formats of the questionnaire were used in the study. A self-administered form was completed by 288 clients and family members, and an interview format was completed by 21 clients who needed more assistance in answering questions.

Subjects

Family members and clients were contacted at one of four sites or groups in Johnson County, Iowa. They included inpatient psychiatry units of the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, a supported-housing program, a residential care facility, and the local chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Clients were adults who had been diagnosed as having a major mental disorder. Those with a single diagnosis of alcoholism or substance abuse were excluded. Family members included parents, siblings, children, and spouses of the ill person.

The supported-housing program for the mentally ill had 70 clients, and staffing was provided primarily by counselors with degrees in a variety of social sciences. The residential care facility had a population of 89 persons, 63 of whom had a severe mental illness. This facility was staffed by a part-time psychiatrist, nurses, social workers, recreational staff, aides, and orderlies.

The study was carried out from December 1993 through May 1994. All clients who met study criteria at all four sites were asked to participate. Questionnaires and cover letters were sent to family members and clients on the mailing list of the local Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Included in each packet was an additional questionnaire for a family member or client who was not on the mailing list. In other settings, clients were invited to participate in the study by either the staff or the study investigators.

Staff members were trained by investigators to conduct the survey in the same systematic manner. Client questionnaires requested the name of a family member to contact, and questionnaires were mailed by the investigators to all family members whose names were provided.

A total of 309 questionnaires were returned. The overall response rate for the study was 56 percent. Some variation in response rates was noted. The rates were 40 percent from the supported-housing program, 53 percent from the Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 56 percent from the residential care facility, and 76 percent from the inpatient units. Diagnoses of the inpatients who refused to participate were analyzed for a one-week period. Compared with the inpatients who participated in the study, those who refused were more likely to have schizophrenia (50 percent versus 23 percent); all who refused had acute psychotic symptoms.

Twenty-three of the returned questionnaires (7 percent) were not included in the analysis because the current residence was not specified. The remaining 286 respondents included 168 clients and 118 family members. Of this total, 79 were matched pairs—a family member and a client. Thus 207 clients were represented in the study either by direct participation or by family participation.

Analysis

The 207 clients were classified into one of three groups on the basis of their responses about where they currently lived. The first group of 58 clients consisted of those who lived in group settings with 24-hour on-site support. Fifty of these 58 clients (86 percent) lived in residential care facilities, and the other eight (14 percent) lived in group homes. The second group of 38 clients consisted of those who lived in supported housing with on-site staff visits. The third and largest group of 111 clients lived in apartments or homes with no on-site professional services.

Individual responses were coded and then manually entered into a standardized computer analysis program, SYSTAT, Version 5 (20). Demographic variables and clinical characteristics were analyzed using descriptive and nonparametric statistics. Groups were compared for independence using Pearson chi square analysis. Associations between family members' and clients' perceptions were examined using correlation analysis.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

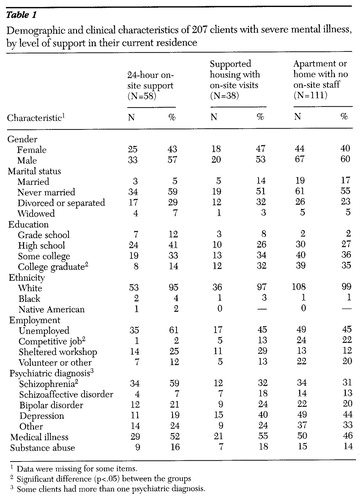

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the three client groups. The mean±SD ages of the clients in group settings, supported housing, and those with no on-site support, were 49.5±15.8, 40.2±11.9, and 38.9±15.5 years, respectively. Clients who lived in group settings were significantly more likely to be older, less educated, unemployed, and diagnosed as having schizophrenia than clients in other settings. On the other hand, those who lived in apartments or homes were more likely to be diagnosed as having depression. Some clients had more than one psychiatric diagnosis.

The diagnostic category "other" included a fairly even distribution of clients with personality disorders, eating disorders, and anxiety disorders. About half of all clients (49.5 percent, or 100 clients) were diagnosed as having chronic medical illnesses, with many individuals having more than one illness. The most common chronic conditions in descending order were arthritis, hypertension, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses.

Current and preferred residence

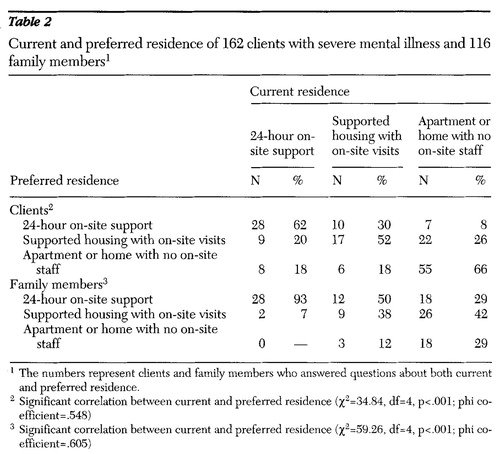

Table 2 compares current and preferred housing from clients' and families' perspectives. Most clients who currently lived in housing with 24-hour on-site support preferred that type of residence. Of the clients who lived in supported housing with on-site staff visits, slightly more than half also preferred that arrangement, while a third preferred housing with 24-hour on-site staffing. The majority of those living in housing with no on-site staff support preferred that option. Overall, a statistically significant association was found between current and preferred housing. Each group preferred their current housing situation above other choices.

A statistically significant association was also found between the current residence of clients and the setting preferred by their families, although families preferred the more supervised settings even more than clients did. For example, on-site 24-hour staffing was preferred by more than 90 percent of family respondents whose ill relative lived in this setting. In contrast, a setting with on-site 24-hour staffing was preferred by 50 percent of families whose relative lived in supported housing with on-site staff visits and 29 percent of families whose relative lived in housing without on-site staff support.

Clients' and families' perception of problems

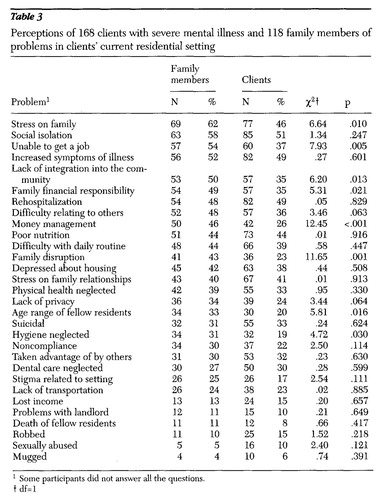

Table 3 compares clients' and families' perceptions of problems in the current setting. Perceptions differed significantly between groups on eight items, with a greater percentage of family members consistently reporting problems. The problem categories in which significant differences were noted between families' and clients' perceptions included interpersonal issues, such as stress on family members, and financial and work-related problems.

Although family members reported a higher incidence of problems than clients, a strong and significant correlation between clients' and families' perceptions of problems was found based on rank order of all 30 problems on the list (Spearman correlation coefficient=.86, p.<001; Kendall tau correlation coefficient=.70, p<.001). The top-ranked problems from the perspectives of both clients and families were interpersonal problems, including stress on the family, social isolation, the client's lack of community integration, the client's difficulty relating to others, and family disruption; treatment issues, including increased illness symptoms and rehospitalization; problems with daily living, including the client's difficulty with routine and poor nutrition; and financial and work issues, including the client's inability to get a job, increased financial responsibilities for the family, and money management. Neglect of physical health was also identified as a problem by about a third of the respondents.

Current housing and perception of problems

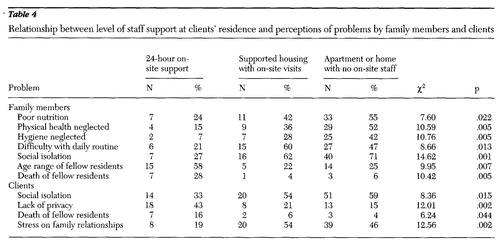

Problems that were found to be significantly associated (p<.05) with the level of support at clients' residences are listed in Table 4. According to family members, clients who did not live in a structured group setting experienced significantly more problems with nutrition, physical health, daily routine, and social isolation. Clients' responses also indicated that social isolation and stress from family relationships increased significantly when clients lived independently. For those who lived in group settings, a lack of privacy, the age range of fellow residents, and the death of fellow residents were significantly more stressful.

Discussion

Of the 162 clients who expressed their preferences in this study, most preferred the type of housing in which they currently lived. This finding contradicts the results of most previous studies that found that clients preferred living independently regardless of their current residence (9). Family members in the study reported here preferred 24-hour on-site staff support above other housing options for most clients; however, if their ill relative was already living in a group setting, they were significantly more likely to prefer a group setting to the other two options. This finding is supported by other studies in which families tend to prefer a higher level of support than clients (19).

Schizophrenia was the predominant diagnosis among clients who currently lived in group settings with 24-hour on-site staff. Research indicates that many persons with schizophrenia lack the ability to create their own internal structure and therefore require structure in the environment to prevent decompensation (13). The prevalence of schizophrenia among residents in this setting may be linked to the recognition by caregivers that these individuals need more structure and support than independent living provides.

Results of the study suggest that an array of housing is needed and that giving clients a choice means ensuring that housing alternatives exist. The separation of staff from housing, as recommended in the supported-housing literature (8), may be an inappropriate arrangement for a large number of clients, particularly those with schizophrenia. The study found that a third of the clients living in a supported-housing arrangement without 24-hour staff support preferred the higher level of structure afforded by a setting with 24-hour on-site staff support.

Although families consistently reported more problems than did clients, a strong correlation was found between clients' and families' perceptions of problems based on the rank order of all 30 problems on the checklist. Stress on family members was the top problem from the family members' perspective and the fourth-ranked problem from the clients' viewpoint. Families whose ill relative lived in a setting with 24-hour on-site support perceived fewer problems than families whose relatives lived in the other two settings.

When clients live in the community, family members are often the primary caregivers. The family viewpoint has rarely been sought in determining the housing and service needs of those with severe mental illness (10). Policy makers should be aware of the sense of frustration and even exhaustion that many family members feel as they deal with their relative's mental illness and should include them as ongoing participants in decision-making groups.

Clients who lived in a setting with 24-hour on-site support, as well as their family members, were significantly less likely to report social isolation than those who lived in the other two settings. This finding reaffirms families' concerns that independent living does not solve the problem of social isolation (10). Community integration is very difficult for many clients who are mentally ill. Pulice and associates (21) found that current regulations for supported housing put undue pressure on clients to live alone, resulting in anxiety, return of symptoms, and even rehospitalization. Symptoms of severe mental illness, particularly those of schizophrenia, often interfere with reaching out to others and making new friends. Furthermore, only 14 percent of the clients in this study were married. Being single creates a high risk for social isolation and loneliness.

Approximately 50 percent of the 207 clients in this study had chronic medical illnesses, and about 15 percent had a substance abuse problem. The percentage of clients with medical illnesses approximates the findings from other studies (22); however, the prevalence of substance abuse is lower than in other studies (23).

Neglect of physical health was cited as a problem by approximately a third of family members and clients. Family members whose ill relative lived in a setting with 24-hour on-site support were significantly less likely to report neglect of physical health as a problem than those with a relative in the other two settings. Neglect of physical health among persons with mental illness has been well documented; the death rate is significantly higher in the mentally ill population than in the general population, and the higher rate is often associated with undiagnosed and untreated chronic medical illnesses (24).

Problems related to the physical setting ranked relatively low; however, they were significantly more stressful for clients who lived in group settings. Clients identified lack of privacy as a problem. The wide age range of residents was particularly stressful to family members. Housing elderly clients with young adult clients may be inadvisable for a variety of reasons, including the death of elderly residents.

Although the findings are limited in their generalizability because of the geographic homogeneity of the participants, the results suggest specific changes in community residential settings that might improve clients' quality of life.

Conclusions

Although supported housing works for many, it is not the answer for all clients. Throughout the deinstitutionalization and rehabilitation literature, the phrase "return the patient to independent living" appears frequently, regardless of whether the goal is realistic or even advisable for all clients (25). We found that persons with severe mental illnesses and their family members prefer a wide array of choices in housing, ranging from 24-hour staffed group settings to independent living with no on-site services.

Because development of adequate housing is a major policy issue, knowing the preferences and needs of a wide range of clients and their families is important. It is particularly important to consider the needs of clients who are the most ill and who are the least likely to respond to surveys of consumer preferences.

Acknowledgments

Minta Wu, Ph.D., provided statistical assistance for the study, which was partly supported by the Alliance for the Mentally Ill of Johnson County, Iowa, and by a research award from the Gamma Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau.

The authors are affiliated with the University of Iowa in Iowa City. Ms. Friedrich is associate professor and Dr. Culp is assistant professor in the College of Nursing. Ms. Hollingsworth is project assistant for the Iowa Consortium for Mental Health in the College of Medicine. Ms. Hradek is an advanced practice nurse in the department of psychiatry in the College of Medicine. Dr. Friedrich is professor in the department of chemistry. Send correspondence to Ms. Friedrich at the College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 207 clients with severe mental illness, by level of support in their current residence

1 Data were missing for some items.

2 Significant difference (p<.05) between the groups

3 Some clients had more than one psychiatric diagnosis.

|

Table 2. Current and preferred residence of 162 clients with severe mental illness and 116 family members1

1 The numbers represent clients and family members who answered questions about both current and preferred residence.

2 Significant correlation between current and preferred residence (χ2=34.84, df=4, p<.001; phi coefficient=.548)

3 Significant correlation between current and preferred residence (χ2=59.26, df=4, p<.001; phi coefficient=.605)

|

Table 3. Perceptions of 168 clients with severe mental illness and 118 family members of problems in clients' current residential setting

1 Some participants did not answer all the questions.

† df=1

|

Table 4. Relationship between level of staff support at clients' residence and perceptions of problems by family members and clients

1. Stroul BA: Community support systems for persons with long-term mental illness: a conceptual framework. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 12:9-26, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Torrey EF: Nowhere to Go: The Tragic Odyssey of the Homeless Mentally Ill. New York, Harper & Row, 1988Google Scholar

3. Torrey EF, Stieber J, Ezekiel J, et al: The Abuse of Jails as Mental Hospitals. Washington, DC, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and Public Citizen Health Research Group, 1992Google Scholar

4. Griffin Francell C, Conn VS, Gray DP: Families' perceptions of burden of care for chronically mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1296-1300, 1988Google Scholar

5. Hatfield AB, Lefley HP: Families of the Mentally Ill: Coping and Adaptation. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

6. Lively S, Friedrich RM, Buckwalter KC: Sibling perception of schizophrenia; impact on relationships, roles, and health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 16:225-238, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nagy M: De-congregating a residential program for people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 12:70-73, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Carling PJ: Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:439-449, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys of mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450-455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Hatfield AB: A family perspective on supported housing. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:496-497, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Wasow M: The need for asylum revisited. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:207-208,222, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Lamb HR: Structure: the neglected ingredient of community treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:1224-1228, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lamb HR: Structure: the unspoken word in community treatment. Psychiatric Services 46:647, 1995Link, Google Scholar

14. Belcher JR, DeForge BR: The appropriate role for the state hospital. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:64-71, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

15. Dewees M, Pulice RT, McCormick LL: Community integration of former state hospital patients: outcomes of a policy shift in Vermont. Psychiatric Services 47:1088-1092, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Lehman AF, Slaughter JG, Myers CP: Quality of life in alternative residential settings. Psychiatric Quarterly 62:35-49, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Housing Committee of the California Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Castaneda D, Sommer R: Patient housing options as viewed by parents of the mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:1238-1242, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

18. Pandiani J, Glesne C: Interpreting divergent results of triangulated research: a review of three studies of housing needs of adults with psychiatric diagnoses. Sociological Practice Review 3:87-93, 1992Google Scholar

19. Rogers ES, Danely KS, Anthony WA, et al: The residential needs and preferences of persons with serious mental illness: a comparison of consumers and family members. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:42-51, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. SYSTAT for Windows: Statistics, Version 5. Evanston, Ill, SYSTAT, 1992Google Scholar

21. Pulice RT, McCormick LL, Dewees M: A qualitative approach to assessing the effects of system change on consumers, families, and providers. Psychiatric Services 46:575-579, 1995Link, Google Scholar

22. Koranyi EK: Morbidity and rate of undiagnosed physical illnesses in a psychiatric clinic population. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:414-419, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Drake RE: Substance abuse and mental illness: recent research. NAMI Advocate 16:5-6, 1995Google Scholar

24. Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D: Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1363, 1996Link, Google Scholar

25. Wasow M: The need for asylum for the chronically mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:162-167, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar