Psychosis Seminars: An Unconventional Approach

Communication between consumers, family members, and mental health professionals can be difficult in everyday practice. Psychosis seminars provide an innovative opportunity for all groups to meet in a neutral forum and share their perspectives without formal responsibilities. They do not provide any form of conventional treatment, and they follow defined rules—for example, the meeting is held in a neutral place after office hours, and the program topics are jointly agreed upon. The seminars have been established mainly in German-speaking countries and are regularly attended by approximately 5,000 people. Some evidence suggests that consumers, family members, and professionals benefit from the seminars in different ways. However, the feasibility and effects of the seminars should be tested more widely and subjected to more systematic research.

Communication and collaboration between consumers, family members, and mental health professionals is often difficult because of different perspectives, interests, and terminologies (1). These difficulties can make all three groups feel equally misunderstood, disappointed, and isolated.

Against this background, we report about psychosis seminars, an unconventional form of dialogue between the three groups. We briefly describe the characteristics and history of the psychosis seminars and the experiences of persons attending them.

Characteristics

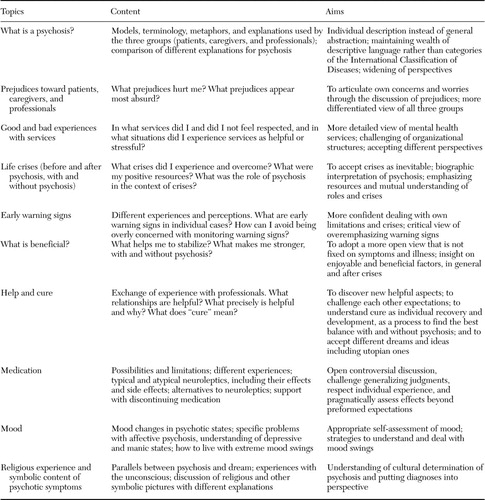

Psychosis seminars are not usual teaching seminars. They are forums to allow a dialogue between consumers, family members, and health care professionals (2,3). Although details of the seminars may vary, there are some defined rules for the meetings. The psychosis seminars are held on neutral grounds—that is, in premises outside of where services are provided and outside of consumer or family member organizations. They are held after office hours and are open to all interested consumers, family members, and professionals. They usually last for about two hours and include a break. The seminars are held regularly and are arranged over a longer period. Most often, the seminars are held once every two weeks and continue for four to 12 months. At the end of a cycle there is a break, after which a new seminar may be started with old and new participants. The seminar has topics that are jointly agreed upon. An example for an agreed program of topics is shown in Table 1. However, the example is only for illustration. In practice, the content of programs can vary substantially. The meetings are chaired by one or more of the participants. Often the chair rotates between participants of the three groups. The psychosis seminars are usually attended by between 20 and 60 people (ideally with equal representation from each group, which is frequently achieved in practice).

Unlike conventional forms of teaching or psychoeducation, in psychosis seminars all participants meet with equal entitlements and without any formal responsibilities. The seminars offer no form of medical treatment. Participants from all three groups attend out of personal interest and in their spare time. The aim of the meetings is a mutually respectful dialogue, which allows participants to learn from each other's perspective and experiences. In this encounter, everyone is regarded as an expert with respect to their own role and experience. Individual experiences are emphasized. Also, participants aim to overcome terminological barriers and rehearse open communication for everyday practice.

History

The first psychosis seminar was organized in Hamburg, Germany, in 1990. Similar to the voice-hearer network in the Netherlands, psychosis seminars originated from a dialogue between a clinician and a consumer. In a conventional teaching seminar with medical students at the local university, both the consumer and the professional realized that talking with each other provided more insight than talking about each other. Subsequently, the consumer and professional issued an open invitation to patients, their family members, and professionals. The first meeting was attended by more than 100 people. The title "seminar" was chosen, despite its academic connotation, to emphasize the learning experience for all participants.

The idea spread quickly across German-speaking countries. There are now approximately 130 regular psychosis seminars in urban and rural areas (www.psychiatrie.de). Approximately 5,000 people are estimated to regularly meet in these seminars to discuss the experience of psychosis and treatment. Outside of German-speaking countries, there have been only sporadic initiatives to establish psychosis seminars.

Several psychosis seminars have widened their goals and aimed to influence the public perception of people with psychotic disorders and of mental health services. Some seminars actively invite journalists and other people who might influence public opinion. Other seminars organize information events at schools as a form of an antistigma campaign.

Perceptions and experiences of participants

Psychosis seminars have not been evaluated by using systematic documentation or experimental trials, which would be incompatible with the philosophy of the seminars and the expectations of a significant proportion of participants. However, on the basis of perceptions and a postal survey of 43 facilitators and chairs and 147 participants of 58 seminars (2,4), a few statements can be made about who attends and whether different groups perceive that they benefit from attending these seminars.

In all three groups, the age of participants varied greatly, and women are slightly overrepresented. Among consumers, soon after the seminars were created most participants were those with long-term contacts with mental health services. However, as time went on more consumers with recent onset of the disorder have participated, as well as an increasing number of people with psychotic disorders, who otherwise avoid any contact with professional services. Consumers who are explicitly critical of services are particularly well represented. Many of the attending family members feel insufficiently supported by health services or live with patients with psychosis who do not accept any form of psychiatric treatment. Among professionals, those with several years of professional experience are overrepresented. However, there are also some students and professionals who recently began working in mental health services.

With respect to the main motivation for each group, patients expect to get actively involved and initiate change in the way mental health care is practiced. Family members are more interested in increasing their knowledge about the illness and sharing their feelings and the learning experience with others. Professionals are interested mainly in reflecting about their own practice and role, and they gain new insights into the processes of psychosis and treatment.

Factual information appears to be most important for family members. Consumers seem to want to be respected with their psychotic experience and to understand their psychosis in the context of their biography and living situation. All three groups appear to benefit from the unusual opportunity to listen to each other without any dependence and responsibility and without a directly shared history within the same family or treatment processes.

Professionals are responsible only if an obvious acute disorder requires immediate medical intervention. However, not a single such case has been reported, and there have not been any reports about physical violence, although verbal aggression can occur. The only responsibility that exists is shared by all three groups—the one for the seminar to be conducted so that it is beneficial and helpful.

Conclusions

Psychosis seminars do not replace conventional services. Rather, they complement them as an alternative forum to engage and learn. The seminars are unlikely to be an attractive and useful option for every consumer, family member, and professional. However, a significant number of people from each group organize the seminars, participate regularly, and appear to benefit in one way or another. The seminars reach consumers and family members who do not feel well supported by services. For all three groups the seminars offer opportunities and benefits that conventional services do not provide.

The described positive effects are plausible, but they do not stand the test of strict criteria that is required of evidence-based medicine. In fact, because the seminars do not offer treatment, despite their potentially therapeutic effects, they may fall outside the realm of evidence-based medicine. Yet, it is common sense that the openness and the atmosphere of honest dialogue in the seminars may be beneficial in various ways.

The seminars are not expensive. Funding is required only to hire a room. However, they require commitment, energy, and a willingness to respect the perspectives of and to learn from other groups. We think it is time to implement these seminars more widely and to subject them to more research for further development.

Dr. Bock is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Hamburg in Germany. Dr. Priebe is with the unit for social and community psychiatry at Queen Mary (University of London) in London, England. Send correspondence to Dr. Priebe at the Newham Centre for Mental Health, London E13 8SP, England (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Examples of programs for psychosis seminars

1. McCabe R, Heath C, Burns T, et al: Engagement of patients with psychosis in the medical consultation: a conversation analytic study. British Medical Journal 325:1148–1151,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bock T, Nika E: For the understanding of psychotherapy and social psychiatry from the perspective of the dialog in the "psychosis-seminar." Psychotherapie Forum 8:117–122,2000Google Scholar

3. Amering M, Hofer H, Rath I: The "First Vienna Trialogue": experiences with a new form of communication between users, relatives, and mental health professionals, in Family Interventions in Mental Illness: International Perspectives. Edited by Lefley HP, Johnson DL. Westport, Conn, London, Praeger, 2002Google Scholar

4. Johannisson A: Bundesweite Erfassung aller zur Zeit bestehenden Psychoseseminare und Befragung von Personen, die an einem Seminar teilnahmen [National Survey of All Existing Psychosis-Seminars in Germany and Interviews of Participants]. Hamburg, Germany, department of psychology, University of Hamburg, 1997Google Scholar