Job Satisfaction of Nurses Who Work in Private Psychiatric Hospitals

Abstract

This study assessed the job satisfaction of nurses who work in private psychiatric hospitals. In 1998 and 1999 an anonymous employee satisfaction survey was completed by all 3,024 employees of 39 for-profit psychiatric hospitals owned by the same hospital corporation. Of this total, 546 were registered nurses (RNs). Generally RNs reported fair levels of satisfaction. They reported high levels of pride in their hospitals but low levels of satisfaction with the parent company. Differences in satisfaction were noted as a function of work shift, supervisory role, work setting, and tenure. RNs were less satisfied than employees in all other hospital job classifications. RNs' low level of satisfaction relative to other positions is concerning.

Little is known about the job satisfaction of psychiatric nurses. This lack of knowledge is problematic, because there is a well-documented connection between job satisfaction and the health and well-being of both psychiatric employees and patients (1). Psychiatric hospitals have been identified as difficult places to work: nurse burnout is common (2), and turnover is high (3). Furthermore, the fiscal challenges that face psychiatric hospitals are also notable (4), and vital organizational economic outcomes are related to worker satisfaction (5). Therefore, psychiatric hospitals must assess levels of satisfaction in their organizations. In this study we examined various aspects of job satisfaction among nurses in private psychiatric hospitals.

Methods

In 1998 and 1999 an anonymous employee satisfaction survey was completed by all 3,024 employees of 39 for-profit psychiatric hospitals owned by the same hospital corporation (6). Of this total, 546 were registered nurses (RNs). The RNs came from various hospital programs, worked various shifts, had differing tenure, and differed in whether they had a supervisory position.

To speed the collection of completed surveys, each employee completed his or her own survey in a small group of 20 to 25 employees. Eighty percent of the respondents at least somewhat agreed that their confidentiality was protected, reducing the likelihood of socially desirable responses.

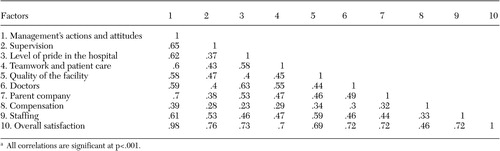

Respondents rated their level of satisfaction on the 100-item survey by using a 5-point Likert scale: 1, poor; 2, fair; 3, good; 4, very good; and 5, excellent. Factor analysis of the survey yielded nine replicable factors (6). These factors included management's actions and attitudes, supervision, level of pride in the hospital, teamwork and patient care, quality of the facility, doctors, parent company, compensation, and staffing. Thirty-seven percent of the variance in satisfaction was explained by management's actions and attitudes, 7 percent by supervision, and 4 percent by pride in the hospital. Each remaining factor accounted for 2 to 3 percent of the variance in satisfaction (6). To examine overall satisfaction we used a global satisfaction index, that is, an additive composite of the nine factors.

Results

RNs in the psychiatric hospitals generally reported fair satisfaction for all the measures (mean scores ranged from 2.38 to 3.62). The RNs were most satisfied with the level of pride in the hospital ("I would recommend this hospital to a patient who needed the care that it offers" and "Patients could brag about the care they receive here") and least satisfied with the parent company ("The parent company makes quality of care the main goal for the hospital" and "The parent company keeps employees informed").

Table 1 shows that several interesting bivariate relationships emerged among the survey factors. Management's actions and attitudes demonstrated the largest mean correlation with all the other factors (mean of .64), including overall satisfaction (r=.98). Therefore, management's actions and attitudes were found to strongly relate to other areas of job satisfaction for the RNs. Compensation demonstrated the lowest mean correlation with the other factors (r=.31), including global satisfaction (r=.46). Compensation is an area of satisfaction that is somewhat distinct from the other satisfaction dimensions.

To examine the extent to which RNs' satisfaction differs as a function of work characteristics, a series of between-group omnibus analyses of variance were conducted. To control for type 1 error, we corrected for the number of omnibus comparisons (N=5), reduced our acceptable level of chance to .01, and computed post hoc analyses by using a Bonferroni correction. In general, levels of overall satisfaction among the RNs did not differ for shift; however, those working night shifts were significantly less satisfied than those working other shifts. RNs without supervisory responsibility were more satisfied than those who were supervisors. In terms of tenure, RNs who had been employed at the hospital for six months or less had relatively high levels of satisfaction, RNs who had been employed for six months to five years had significantly lower levels of satisfaction, and RNs who had been employed longer than five years had a significant rebound in satisfaction, similar to levels reported within six months of hire. The RNs who worked in partial or outpatient programs reported being significantly more satisfied than those who worked in residential treatment centers. Satisfaction did not differ as a function of hospital unit or program.

To compare the satisfaction of RNs with that reported by individuals in other positions, we used multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA), a conservative test that controls for type 1 error. The omnibus MANOVA was significant for six of the nine satisfaction dimensions. To clarify the omnibus test, multiple comparisons were conducted by using a Bonferroni correction. Results of these analyses suggest that RNs were as satisfied with their jobs as licensed practical nurses, nurses' assistants, and other nursing employees with less formal training. Relative to RNs, nurses with less formal training were more satisfied with the quality of the hospital facilities but less satisfied with staffing and less satisfied overall. Administrators (accounting, finance, and human resources), other health professionals (doctors and psychologists), operations employees (janitorial staff, food services employees, and physical plant employees), and other employees (employees in various jobs that were difficult to classify) were more satisfied with their jobs than RNs. This finding presents an interesting paradox. Not only did RNs generally report fair satisfaction, they tended to be less satisfied on most measures than psychiatric hospital employees in other positions.

Discussion

In this study we attempted to describe in some detail the job satisfaction of RNs who work in private psychiatric hospitals. The results suggest that psychiatric RNs are fairly satisfied with their jobs. However, relative to most other employees, from housekeepers to psychiatrists, RNs reported the lowest levels of job satisfaction. Their relatively low satisfaction may be cause for concern because of nursing shortages and hospital finances and because it may affect patient outcomes. Furthermore, nurses in supervisory positions were particularly dissatisfied. These findings are consistent with research from medical and surgical hospitals, where both job satisfaction and patient care have suffered as a result of understaffing, falling nurse-to-patient ratios, inadequate nursing education, and overworked nurse managers (7,8).

Hospital managers should take note that their actions and attitudes have an impact on virtually every other dimension of satisfaction (6). One practical implication of this finding is that if RNs are dissatisfied with their immediate supervisors, they are likely to be dissatisfied in other areas. Conversely, satisfaction with management will likely be seen in conjunction with RNs' satisfaction in other areas. Private psychiatric hospitals would do well to work with supervisors on improving their skills and abilities to work with RNs. In particular, acknowledging and handling complaints, treating employees with respect, and acting in an ethical manner are particularly good strategies that managers can use to increase job satisfaction in the psychiatric hospital setting (6). Contrary to common belief, compensation was not strongly related to other satisfaction dimensions. RNs who work in private psychiatric hospitals can be unhappy with their compensation packages and make independent judgments about other dimensions of satisfaction.

Our study had a number of important limitations. All the results reported here are based on a self-report measure of job satisfaction. Future studies should include both self-report and objective indexes of job satisfaction. Our study looked at only 39 hospitals, all of which were owned by the same for-profit company. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings is limited. We were unable to ask our sample a number of important demographic questions, such as ethnic and cultural identity and level of education. Ethnographic and other in-depth studies, as well as those designed to specifically examine psychiatric hospitals, would help our understanding of the satisfaction of this understudied group of employees.

Conclusions

RNs who work in private psychiatric hospitals report absolute and relative levels of satisfaction that are not ideal. Furthermore, if RNs can be retained from their sixth month through their fifth year of tenure, their satisfaction is likely to rise. Any efforts that can be undertaken during this time frame to improve morale and working conditions would likely pay dividends in terms of improved retention. Therefore, supervisors need to be sensitive to RNs' concerns and address them as best they can with their limited resources (7).

Supervisors, with relatively little financial investment, can act ethically, keep politics to a minimum, provide RNs with greater recognition, and demonstrate cooperation with and concern for the communities in which the hospital resides. All these actions are valued by the typical RN (9). Given the ongoing problems associated with the nursing shortage, serious attempts at understanding and improving nurses' job satisfaction are critical.

Dr. Aronson is affiliated with the Social Science Research Institute at the Pennsylvania State University, 105 Health and Human Development East Building, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Correlations between job satisfaction factors among 465 registered nurses in 39 for-profit psychiatric hospitals owned by thesame hospital corporationa

a All correlations are significant at p<.001.

1. Landerweed JA, Boumans NPG: Nurses' satisfaction and feeling of health and stress in three psychiatric departments. International Journal of Nursing Studies 25:225–234, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Happell B, Martin T, Pinikahana J: Burnout and job satisfaction: a comparative study of psychiatric nurses from forensic and a mainstream mental health service. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 12:39–47, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Sumner J, Townsend-Rocchiccioli J: Why are nurses leaving nursing? Nursing Administration Quarterly 27:164–171, 2003Google Scholar

4. Grimmy AE, Baumbach CR: Psychiatric hospitals. Appraisal Journal 69:52–67, 2001Google Scholar

5. Chan KC, Gee MV, Steiner TL: Employee happiness and corporate financial performance. Financial Practice and Education 10:47–52, 2000Google Scholar

6. Aronson KR, Sieveking N, Laurenceau JP, et al: Job satisfaction of psychiatric hospital employees: a new measure of an old concern. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 5:437–452, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Aiken LH, Gwyther ME, Friese CR: The registered nurse workforce: infrastructure for health care reform. Statistical Bulletin of the Metropolitan Insurance Company 76:2–9, 1995Google Scholar

8. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al: Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 288:1987–1993Google Scholar

9. Aronson, KR, Laurenceau, JP, Sieveking N, et al: Job Satisfaction as a function of job level: a possible explanation for job dissatisfaction in psychiatric hospitals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, in pressGoogle Scholar