Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among National Health Insurance Enrollees in Taiwan

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: About 96 percent of all residents of Taiwan were enrolled in the National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 2000. This study used claims data from the NHI database to determine the prevalence of and the demographic characteristics that are associated with psychiatric disorders. METHODS: A total of 200,432 persons, about 1 percent of Taiwan's population, were randomly selected from the NHI database. Persons under the age of 18 years and persons who were not eligible for NHI in 2000 were excluded, leaving 137,914 persons available for this study. Data for enrollees who had at least one service claim during 2000 for ambulatory or inpatient care for a principal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were classified into one of the psychiatric disorder categories according to ICD-9-CM diagnostic criteria. Data from the 2000 NHI study were compared with data from a 1985 community survey, the Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project, to determine how the prevalence of psychiatric disorders changed over the 15-year period. RESULTS: The one-year prevalence of any major psychiatric disorder, any minor psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder were 1.37 percent, 4.26 percent, and 5.30 percent, respectively. The differences in prevalence between the sexes were significant for five major and nine minor psychiatric disorders. The prevalence for eight psychiatric disorders were lower in the 2000 NHI study than in the 1985 community survey. However, the prevalence of schizophrenic disorder was found to be higher in the 2000 study and the prevalence of bipolar disorder was found to be the same in both studies. CONCLUSIONS: Because the prevalence of psychiatric disorders were generally lower in this study and in the 1985 community survey than those in other countries, it was concluded that both major and minor psychiatric disorders were undertreated in Taiwan. It is necessary for the public health department and the general population to emphasize mental illness education, prevention, and treatment in Taiwan.

Taiwan implemented a National Health Insurance program (NHI) in March 1995, which offered a comprehensive, unified, and universal health insurance program to all citizens. NHI covers ambulatory care, inpatient care, dental services, and prescription drugs. Before the implementation of NHI, there were more than ten social insurance programs, which offered coverage for only 59 percent of the entire population of Taiwan. About 96 percent of all residents of Taiwan—21,400,826 persons—were enrolled in the program in 2000. Because the program offers insurance to all persons in Taiwan, a fair share of risk pooling for NHI should be expected. All citizens who have established a registered domicile for at least four months in Taiwan or in three other remote islands (Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu) can be enrolled in NHI. Persons who do not have Taiwan citizenship but who do have a Taiwan Alien Residence Certificate may also participate in the program four months after a certificate is issued.

Ninety-one percent of the medical institutions in Taiwan were affiliated with NHI in 2000. NHI's expenditures in 2000 were $9 billion in U.S. dollars, equivalent to 3 percent of Taiwan's gross domestic product (1). Although expenditures for all psychiatric disorders combined represent only 3 percent of NHI's budget at the present time, this amount is projected to increase gradually, as has been the case in other countries (2).

In the United States a number of researchers have used Medicaid and Medicare claims data to analyze the prevalence, treatment, and costs of psychiatric disorders (3,4,5). Therefore, we used NHI data to analyze the prevalence and treatment rates of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan. We compared the data from NHI with previous data obtained from the 1985 community survey, the Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project (6,7), and calculated the percentage of persons in Taiwan who sought psychiatric treatment.

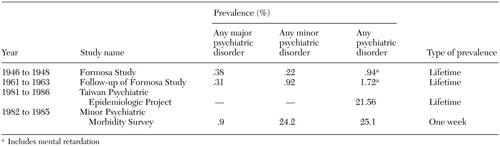

In a previous census survey in Taiwan, the Formosa Study, which was conducted from 1946 to 1948, the lifetime prevalence rate for all psychiatric disorders was .94 percent (8). A follow-up of the Formosa Study that was conducted from 1961 to 1963 found that this rate had increased to 1.72 percent (9). No significant difference was seen between these two surveys in the lifetime prevalence rate of any major psychiatric disorder, including schizophrenia, manic depressive disorder, senile psychoses, and other psychoses. The 1946 to 1948 rate was .38 percent and the rate for 1961 to 1963 was .31 percent. However, the lifetime prevalence rate of any minor psychiatric disorder, including neurotic disorders and personality disorders, increased from .22 percent to .92 percent. This increase is significant, and it implies that social changes, such as industrialization and modernization, increased the prevalence rate of minor psychiatric disorders (9,10).

Another community survey, the Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project, which was conducted from 1981 to 1986, used the Chinese modified Diagnostic Interview Schedule as a standardized tool. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule was also used by the National Institute of Mental Health in the United States for a large-scale epidemiological study known as the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. The Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project revealed that the lifetime prevalence rate of any psychiatric disorder in Taiwan was 21.56 percent in the 1985 community survey (6,7). The project also showed that the lifetime prevalence rates for both major and minor psychiatric disorders increased from the rates that were found in the 1961 to 1963 census survey, possibly because of social change, industrialization, urbanization, or different study designs and diagnostic instruments (6,7). However, the Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project showed that Taiwan's lifetime prevalence rate of any psychiatric disorder was significantly lower than the U.S.'s rate of 35.55 percent (6). In addition, the lifetime prevalence rates of many psychiatric disorders in Taiwan were lower than those found in eight other countries that conducted similar studies during the same period (6,7,11,12,13,14).

Another community survey, the Minor Psychiatric Morbidity survey, which was conducted from 1982 to 1985 in Taiwan and which used the Chinese Health Questionnaire and the modified Chinese Version of the Clinical Interview Schedule, revealed that the one-week prevalence rates of any major psychiatric disorder and any minor psychiatric disorder were .9 percent and 24.2 percent, respectively (10). The prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders found in these previous studies are shown in Table 1.

Our study investigated the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders among NHI enrollees in Taiwan and determined which demographic factors—age, sex, insured amount (which was determined by the wage of the insured), residential area, and nationality—were associated with these disorders (15). We anticipate that our data will provide information that could influence future policy making. Our study also offers precious evidence-based data on mental health care for other countries to use.

Methods

Sample

Researchers at the National Health Research Institute used identification cards and birth dates to verify unique persons in the Bureau of NHI population database and gave each person a series number to construct a sampling frame. The National Health Research Institute then compiled a database of 200,432 randomly selected persons, about 1 percent of the population, for use in a related health insurance study (16). No statistically significant differences in age or sex were found between the group that was selected and all enrollees. The data consisted of ambulatory care and inpatient records as well as the registration files of NHI enrollees.

Enrollees were excluded from our study if they had not been eligible for NHI during 2000. As a result of this criterion, 14,542 persons were excluded. An additional 47,976 persons under the age of 18 years were excluded from our study. The final sample consisted of 137,914 persons. Data for persons who had at least one service claim in 2000 for either ambulatory or inpatient care, with the principal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, were categorized into one of the psychiatric disorder classifications according to International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic criteria (17). We divided psychiatric disorders into any major psychiatric disorder and any minor psychiatric disorder. Major psychiatric disorders included ICD-9-CM codes 290 through 298. Minor psychiatric disorders included ICD-9-CM codes 300 through 316, excluding 303 through 305 and 312 through 315. Major depressive disorder is grouped with affective psychoses; in DSM-III-R it is called major depression. In our study it was classified as a mood disorder and was coded as 296.x. Neurotic depression in ICD-9-CM—called dysthymia in DSM-III-R—was coded as 300.4. The "any psychiatric disorder category" consisted of both major and minor psychiatric disorders.

When claims data showed that a person had two or more types of psychiatric disorders, we established a method to decide which diagnosis should be considered the primary diagnosis to be used in the study. In Taiwan, patients who have one or more major psychiatric disorders, including ICD-9-CM codes, can apply for catastrophic illness registration (CIR) cards, which are provided by the Bureau of NHI. These enrollees do not make copayments for mental health care. For persons who had two or more major psychiatric disorders listed in the claims data, the diagnosis listed on the CIR card was used. For persons without CIR cards, we chose the diagnosis associated with inpatient treatment (by frequency), and for persons with no inpatient stays, we chose the diagnosis associated with outpatient care (by frequency), followed by the diagnosis that was assigned by a psychiatrist. For persons with two or more minor psychiatric disorders, we followed a similar algorithm, except these persons did not have CIR cards.

Data for demographic variables—including age, sex, insured amount, residential area, and nationality—were obtained directly from the National Health Research Institute files. Four age groups were used: 18 to 24 years (22,436 enrollees, or 16.3 percent), 25 to 44 years (63,256 enrollees, 45.9 percent), 45 to 64 years (35,731 enrollees, 25.9 percent), and 65 years or older (16,491 enrollees, 12 percent). Data for 68,709 males (49.8 percent) and 69,202 females (50.2 percent) were obtained for our study. The insured amount was classified into one of five categories: fixed insurance premium (which indicated the lowest socioeconomic status, U.S. $32 (New Taiwan [NT] $1,007; 15,086 enrollees, or 10.9 percent), dependent (no premium information was available for dependents; 32,189 enrollees, or 23.3 percent), less than U.S. $640 (NT $20,000; 50,569 enrollees, or 36.7 percent), U.S. $640 to $1,280 (NT $20,000 to $39,999; 26,480 enrollees, or 19.2 percent), and U.S. $1,281 or more (NT $40,000 or more; 13,590 enrollees, or 9.9 percent). Residential area was divided into four areas: metropolitan (36,756 enrollees, or 26.6 percent), urban (45,405 enrollees, or 32.9 percent), suburban (18,422 enrollees, or 13.4 percent), and rural (37,331 enrollees, or 27.1 percent). Nationality was divided into persons who were native Taiwanese (133,636 enrollees, or 96.9 percent) and persons who were not native Taiwanese (4,278 enrollees, or 3.1 percent).

Insured amount is based on and approximate to the monthly wage of the insured and ranges from NT $15,840 to NT $87,600. For the insured group of wage earners, the total monthly premium of an insured family is the insured amount times the premium rate (4.55 percent in 2000) times the employee contribution rate (30 percent) times the (1+number of dependents). For example, for an insured family who has an insured amount of NT $42,000 and two dependents, the total monthly premium of the insured family is NT $1,720 (U.S. $55.1) [NT $42,000 × 4.55 percent × 30 percent × (1+2)=NT $1,720 (U.S. $55.1)]. For the insured group without salaried income, the average premium remained at NT $1,007 (U.S. $32) in 2000.

Statistical analysis

The differences between the sexes in the prevalence rates of all psychiatric disorders were analyzed by using chi square tests. Multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the significant factors associated with a major psychiatric disorder, a minor psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder. The regression analysis controlled for the other covariates, which include sex, insured amount, residential area, and nationality. SAS version 8.0 was used to link and analyze the data. The significance level was set at .05.

Results

Table 1 shows the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders that were found in previous studies in Taiwan.

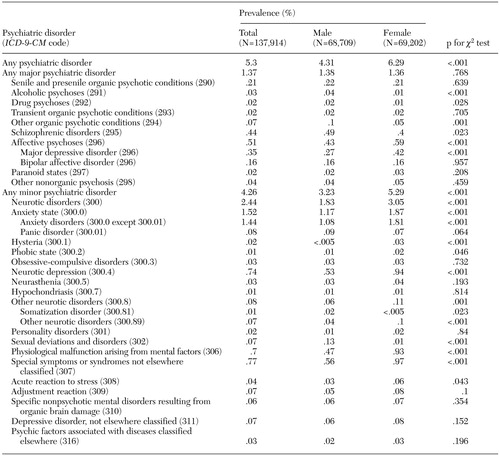

Table 2 shows the results of the 2000 NHI study for the prevalence rates, both overall and by sex, of 29 psychiatric disorders, including ten major psychiatric disorders and 19 minor psychiatric disorders. The one-year prevalence rates of any psychiatric disorder, any major psychiatric disorder, and any minor psychiatric disorder were 5.3 percent, 1.37 percent, and 4.26 percent, respectively. Generally, females had significantly higher prevalence rates in the categories of any minor psychiatric disorders and any psychiatric disorders, whereas no significant difference by sex was found in the category of any major psychiatric disorder. Females had significantly higher prevalence rates for nine disorders: major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, hysteria, phobic state, neurotic depression, other neurotic disorder, physiological malfunction arising from mental factors, special symptoms or syndromes not elsewhere classified, and acute reaction to stress. On the other hand, males had significantly higher prevalence rates for five disorders: alcoholic psychoses, drug psychoses, other organic psychotic conditions, schizophrenic disorder, and sexual deviations and disorders. The prevalence rates for the other 15 disorders were not significantly different with respect to sex.

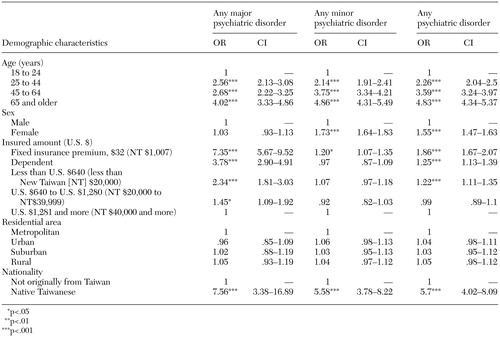

Table 3 shows the results of a logistic regression analysis that determined which demographic characteristics were associated with psychiatric disorders. The prevalence rates of any major psychiatric disorder and any minor psychiatric disorder increased significantly with age. No significant difference was found between the sexes in the prevalence rate for any major psychiatric disorder. However, prevalence rates were significantly higher for females than for males in the categories of any minor psychiatric disorder and any psychiatric disorder. For persons with an insured amount lower than U.S. $1,281 (NT $40,000) (including the dependent group and the fixed insurance premium group), the prevalence rate for any major psychiatric disorder was significantly higher. Persons with a fixed insurance premium had a significantly higher prevalence rate for any minor psychiatric disorder than did persons with an insured amount equal to or higher than U.S. $1,281 (NT $40,000). No significant differences were found among persons who lived in different residential areas for the three categories of psychiatric disorders. Persons who were native to Taiwan had higher prevalence rates for any major psychiatric disorder, any minor psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder than persons who were not native to Taiwan.

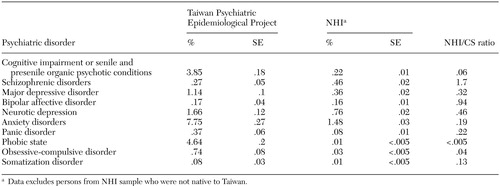

Table 4 compares the prevalence rates of ten psychiatric disorders in the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project with the rates in the 2000 NHI study. In this comparison we excluded persons who were not native to Taiwan from the NHI sample, because no equivalent population was surveyed in the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project. The prevalence rates for eight psychiatric disorders were lower in the 2000 NHI study than in the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project. However, the prevalence rate of schizophrenic disorder was found to be higher in the 2000 study, and the prevalence rate of bipolar disorder was the same for the two studies. Approximately equal prevalence rates were seen for bipolar affective disorder in both studies.

Discussion

This study was the first one to use data from the Bureau of NHI to measure the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan. Also, this was the first study to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders since the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project. Approximately 96 percent of the population of Taiwan enrolled in NHI, which provided a very important database for us to use in the study of the prevalence of and the factors associated with mental disorders. The one-year prevalence rates of any major psychiatric disorder, any minor psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder were 1.37 percent, 4.26 percent, and 5.30 percent, respectively. These rates were lower than those found in previous community studies (6,7,10).

Females had higher prevalence rates in major depressive disorder and several minor psychiatric disorders, which is consistent with previous community findings that showed a higher prevalence of major depressive disorder, anxiety, and psychophysiological disorders (7,10). Males had higher prevalence rates of schizophrenic disorder and other organic psychotic conditions in our study, which indicated that more male patients with these disorders sought medical treatment. Generally, schizophrenic disorder is equally prevalent among males and females (2). Males had higher prevalence rates of alcoholic psychoses and drug psychoses, supporting previous findings that indicated that males usually have more severe substance use problems (7,10). However, in our study we could not examine data that showed the prevalence of alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence, because NHI does not reimburse patients for treatment for a substance use disorder unless they also suffer from a psychotic state, such as alcoholic or amphetamine psychoses.

In the logistic regression analysis of the demographic variables, which determined which variables were associated with the prevalence of psychiatric disorders, we concluded that the prevalence rates for any major psychiatric disorder and any minor psychiatric disorder increased with age. This result indicated that we need to emphasize the use of psychiatric evaluations and mental health care in the elderly population.

Females had a significantly higher prevalence rate for any minor psychiatric disorder and any psychiatric disorder, which is similar to the findings of previous community surveys that revealed the influence of biological and psychosocial factors on females (7,10). This result indicated that we must emphasize the prevention and treatment of minor psychiatric disorders among females.

Persons with an insured amount that was lower than U.S. $1,281 (NT $40,000)—including those with a fixed insurance premium and those in the dependent group—had significantly higher prevalence rates for any major psychiatric disorder. We concluded that a higher rate of any major psychiatric disorder was positively correlated with a lower socioeconomic status, but we could not determine whether the lower socioeconomic status was a cause or a result of the increased rate. Moreover, the lowest socioeconomic status (fixed insurance premium) was significantly associated with prevalence of minor psychiatric disorders, which suggested that this group experienced more psychosocial stress. Thus we should emphasize mental health promotion in persons with lower socioeconomic status.

No significant differences were found for the three types of psychiatric disorders in terms of residential area. This result was inconsistent with the findings of the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project, in which persons in small towns and rural villages had a higher prevalence rate of minor psychiatric disorders than those in metropolitan areas (7). The data we used reflected the site where the insurance unit was located, not the actual place of residence. However, no consistent relationship between residential area and psychiatric disorders has been reported in other studies (7,15). Several studies have reported increased rates of schizophrenia among immigrants (18,19). In our study, native Taiwanese had higher prevalence rates of any major psychiatric disorder, any minor psychiatric disorder, and any psychiatric disorder. This result indicated that most persons who were not native to Taiwan may have received physical and mental examinations before they entered the country. A cultural gap may have also hindered persons who were not native to Taiwan from seeking psychiatric treatment.

Many significant changes have taken place during the past 15 years in Taiwan, such as increased modernization, industrialization, and, of course, democratization. Nevertheless, a comprehensive community survey of psychiatric disorders has not been performed since 1985. Therefore, we compared the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project with the 2000 NHI study to determine how the prevalence rates of ten psychiatric disorders changed over the 15-year period. The prevalence of schizophrenic disorder was higher in the NHI study (.46 percent) than in the community survey (.27 percent, or .31 percent if we include schizophreniform disorder). Because of these data, we concluded that most patients with schizophrenic disorders received treatment in Taiwan under the NHI program. Otherwise, several factors should be considered, such as the 15-year gap, different sampling methods (for example, community surveys may lose contact with persons who are admitted to hospitals), and different diagnostic criteria (19). Bipolar affective disorder showed an approximately equal prevalence in the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project and the 2000 NHI study, which indicated that most patients with bipolar affective disorder also received treatment. However, the other eight psychiatric disorders showed much higher prevalence rates in the community survey than in the NHI study, which leads us to believe that psychiatric disorders are undertreated and underdiagnosed in Taiwan (6,7,20).

We also found that the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders in the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project in Taiwan were generally lower than those found in other countries that used the same study design during the same period (6,7). The lower prevalence rate of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan possibly resulted from methodologic, cultural, and social factors as well as cross-national differences. Many people in Taiwan still have the impression that psychiatric disorders carry a stigma, which makes them hesitate to search for optimal treatment. In particular, the prevalence of major depressive disorder was strikingly low in both the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project (1.14 percent) and our NHI study (.35 percent). We concluded that major depressive disorders in Taiwan are both underdiagnosed and undertreated. Total health expenditures in Taiwan, at 6 percent of Taiwan's gross domestic product, are low compared with Germany (10.7 percent of the gross domestic product) and the United States (13 percent of the gross domestic product) (22,23). The expenditure for psychiatric disorders as a proportion of health spending (3 percent) is low compared with those in Western countries (1,2), which is in agreement with our study's finding of a low treated prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Using insurance data had many advantages for our study, including a large database that was available and the savings of time and money that would have been needed to perform psychiatric assessments. Our study used a sample that was randomly selected to prevent selection bias. However, we faced some limitations, such as the difficulty in determining the reliability and validity of the secondary data and the difficulty in determining a psychiatric disorder classification in light of the occurrence of overdiagnoses and underdiagnoses, dual diagnoses, and primary and secondary diagnoses in the data (24). Although we adopted some methods to manage these problems, we could not completely overcome them. Also, there was a 15-year gap between the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project and the NHI study, which made it difficult to compare the two studies. There is an inevitable bias in the comparison of data from the NHI study and the Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project, because the NHI data reflected rates of treatment for psychiatric disorders, whereas the community survey examined the actual rates of the disorders. We must also consider the implications of comparing the rates we found with those in other studies because of different study designs and instruments.

Conclusions

Because the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders were found to be lower in this study and in the previous community survey than in other countries, we concluded that both major and minor psychiatric disorders are undertreated in Taiwan. The public health department and the general populace should emphasize mental illness education, prevention, and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 91053 from the Taiwan Department of Health.

Dr. Chien, Dr. Y. J. Chou, Mr. Lin, and Dr. P. Chou are affiliated with the Institute of Public Health at National Yang Ming University, 155 Li-Nong Street, Section 2, Peitou, Taipei 112 Taiwan (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Chien is also with the department of community psychiatry at Bali Mental Hospital in Taipei. Dr. Y. J. Chou is also with the department of social medicine at National Yang Ming University. Mr. Lin and Dr. P. Chou are also with the Community Medicine Research Center at National Yang Ming University. Dr. Bih is with the department of child and adolescent psychiatry at Bali Mental Hospital in Taipei and with the Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine at National Taiwan University in Taipei.

|

Table 1. Results from previous studies showing the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan

|

Table 2. Prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders by sex determined by a survey of year 2000 claims data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance program

|

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of data from Taiwan National Health Insurance program enrollees (N=137,914) to determine demographic characteristics associated with psychiatric disorders

|

Table 4. Prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan found in a comparison of the 1985 Taiwan Psychiatric Epidemiological Project and the 2000 National Health Insurance (NHI) study

1. Taiwan Public Health Report 2001, Taipei, Taiwan, Department of Health, Executive Yuan Press, 2002Google Scholar

2. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ: Synopsis of Psychiatry, 8th edition. New York, Williams & Wilkins, 1998Google Scholar

3. Husaini BA, Levine R, Summerfelt T, et al: Prevalence and cost of treating mental disorders among elderly recipients of Medicare services. Psychiatric Services 51:1245–1247, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Husaini BA, Sherkat DE, Levine R, et al: Race, gender, and health care service utilization and costs among Medicare elderly with psychiatric diagnosis. Journal of Aging and Health 14:79–95, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Dixon L, Lyles A, Smith C, et al: Use and costs of ambulatory care services among Medicare enrollees with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:786–792, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Compton WM III, Helzer JE, Hwu HG, et al: New methods in cross-cultural psychiatry: psychiatric illness in Taiwan and the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1697–1704, 1991Link, Google Scholar

7. Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:136–147, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lin TY: A study of incidence of mental disorders in Chinese and other cultures. Psychiatry 16:315–335, 1953Google Scholar

9. Lin TY, Rin H, Yeh EK, et al: Mental Disorders in Taiwan Fifteen Years Later: A Preliminary Report. Honolulu, Mental Health Research in Asia and the Pacific, East-West Center Press, 1969Google Scholar

10. Cheng TA: A community study of minor psychiatric morbidity in Taiwan. Psychological Medicine 18:953–968, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276:293–299, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: The cross-national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55(suppl):5–10, 1994Google Scholar

13. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry l54:305–309, 1997Google Scholar

14. Hwu HG, Chang IH, Yeh EK, et al: Major depressive disorder in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:497–502, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Mcgonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. National Insurance Research Database, Taipei, Taiwan. National Health Research Institutes, 2002. Available at www.nhri.org. tw/nhirdGoogle Scholar

17. ICD-9-CM English-Chinese Dictionary. Taipei, Taiwan, Chinese Hospital Association, Chinese Hospital Association Press, 2000Google Scholar

18. Harrison G, Owens D, Holton A, et al: A prospective study of severe mental disorder in Afro-Caribbean patients. Psychological Medicine 18:643–657, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wessely S, Castle D, Der G, et al: Schizophrenia and Afro-Caribbeans: a case-control study. British Journal of Psychiatry 159:795–801, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Warner R, de Girolamo G: Epidemiology of mental disorders and psychosocial problems: Schizophrenia. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1995Google Scholar

21. Yeh EK, Hwu HG, Chang LY, et al: Lifetime prevalence of cognitive impairment by Chinese-modified NIMH diagnostic interview schedule among the elderly in Taiwan communities. Neurolinguistics 5:83–104, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

22. OECD Health Data 2002, Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2002Google Scholar

23. Lu JR, Hsiao WC: Development of Taiwan's National Health Account. Taiwan Economic Review 29:547–576, 2001Google Scholar

24. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69–71, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar