Course of Patients With Histories of Aggression and Crime After Discharge From a Cognitive-Behavioral Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patients exhibiting aggressive or criminal behavior present a challenge to treaters and caregivers. After discharge from an inpatient facility, such patients are at high risk of rehospitalization and rearrest. A long-term behaviorally based cognitive skills program was developed and administered to a group of such high-risk inpatients. The authors report the results of a postdischarge follow-up of this group. METHODS: After patients entered the inpatient treatment program, their psychiatric and criminal histories were recorded, and a battery of psychological measures were administered, including IQ tests and the Hare Psychopathy Checklist. After discharge, multiple sources were used to obtain information about patients' outcomes. RESULTS: Eighty-five patients were followed for between six months and two years after discharge. Thirty-three of these patients (39 percent) remained stable in the community, 35 (42 percent) were rehospitalized, and 17 (20 percent) were arrested. Several variables that were ascertained before discharge predicted rehospitalization or arrest rates: comorbid antisocial personality disorder, higher score on the Psychopathy Checklist, history of arrests for violent crimes, and history of a learning disability. In addition, patients who developed substance use problems or did not adhere to medication treatment after discharge were more likely to be rehospitalized or arrested. CONCLUSIONS:Arrest rates were low compared with those observed in studies with similar populations. Although this outcome may be attributable to the treatment program, this naturalistic study could not prove that. The predictors of poor outcome may be used to develop a follow-up treatment program that focuses more resources on patients who are at the highest risk.

Aggressive and criminal behavior among persons with mental illness has been subject to intense scrutiny (1). It appears that a small subgroup of persons with mental illness, perhaps 5 percent (2), is responsible for a majority of such acts. Many of these patients have a history of arrest and incarceration. Moreover, these offenders have high rates of rearrest and rehospitalization after they are released into the community. Treatment programs for mentally ill offenders have been scarce, and programs on which data have been published have high rearrest rates. In a 12-month follow-up study, Harris and Koepsell (3) found a 68 percent rearrest rate. In a 36-month follow-up study, Ventura and colleagues (4) found a 72 percent rearrest rate. In that study, 39 percent of the participants were rearrested for violent crime.In a study by Feder (5), 48 percent ofthe mentally ill offenders were rehospitalized and 64 percent were rearrested during a 13-month follow-up period (19 percent for a violent crime).

Among patients who were newly admitted to a New York City state psychiatric hospital, 39 percent had been charged with a felony, 17 percent were admitted from a correctional setting, and 34 percent had a history of incarceration (6). Responding to the needs of this patient population, the New York State Office of Mental Health developed a specialized program for patients with serious mental illness and a history of repeated aggression or crime, or both. The program, called STAIR (System for Treatment and Abatement of Interpersonal Risk), has been available to inpatients since 1997 at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center, a state hospital that serves the indigenous population of New York City. The program's purpose is to break the cycle of repeated hospitalization and incarceration.

STAIR modifies an established cognitive skills program (7,8) and enhances it with a behavioral reward structure called the step system, in which attainment of each step provides a set of rewards and privileges. Six cognitive skills are taught: problem solving, creative thinking, value enhancement, social skills, critical reasoning, and managing emotions. Each skill is taught over a series of three to ten lessons per skill. Skills are taught in 45-minute small-group sessions two times a week. The program consists of 72 sessions.

A peer-run 12-step substance abuse program completes the curriculum. All patients are provided with standard psychopharmacologic management. A psychological evaluation is also part of the STAIR program. After completion of the program and discharge into the community, each patient is assigned a case manager and receives standard psychiatric follow-up. A detailed description of the program is available from the authors on request.

Patients are referred to STAIR by their treatment teams from the Manhattan Psychiatric Center and from other New York City state psychiatric hospitals. None of the patients are prisoners. All patients are civil patients. Their hospitalization is either voluntary or involuntary, as defined by New York State mental health law. Admission criteria and clinical appropriateness is evaluated for each potential candidate. The candidates are educated about the program. The transfer to the STAIR program is guided by the same rules as for any other ward-to-ward transfer. As with other clinically determined transfers from one treatment program to another within the hospital, informed consent is not required. Once in STAIR, patients can decline to participate in the treatment activities without any deleterious consequences to their rights. STAIR staff make an effort to motivate the patients to participate in the activities. However, patients who consistently refuse to participate are transferred back to regular psychiatric wards.

Robinson (9) reported that the original cognitive skills program reduced rearrest and reconviction rates in the one-year follow-up of 1,444 federal offenders by 11 percent compared with 379 control offenders. However, this population of offenders had no documented psychiatric history.

Factors associated with aggressive or criminal behavior have been studied in cohorts of psychiatric patients who have been discharged from general psychiatric hospitals. Noncompliance with outpatient treatment (10,11), postdischarge substance abuse (12,13), history of head injury (14), low IQ(15), and homelessness (16) have been associated with an increased likelihood of aggressive or criminal behavior by mentally ill persons in the community.Factors most frequently associated with hospital readmission include aggressive or threatening behavior, drug or alcohol abuse, and persistent psychiatric symptoms (17).Similar factors associated with readmission or arrest have been observed in patient samples selected for high risk of aggressive or criminal behavior (18). Psychopathy is a predictor of rearrest for violent offenses among criminal offenders with schizophrenia (19).

In this article we report the rates of rehospitalization, rearrest, and postdischarge substance abuse as well as the rates of compliance with treatment in the group of clients enrolled in the follow-up outpatient component of the STAIR program. We explore whether the factors that predict criminal offense in untreated populations of criminal offenders are also predictive in the population of mentally ill offenders who have been exposed to a targeted cognitive-behavioral treatment program. In keeping with research findings summarized elsewhere (1), we hypothesized that psychopathic personality, lower IQ, noncompliance with medication treatment, and postdischarge substance abuse would be associated with higher rates of rehospitalization and rearrest.

In summary, much is known about the behavior of psychiatric patients after their discharge from hospitals where they received usual clinical treatment. Some information is available about the behavior of "normal" offenders after their release from prisons where they participated in a behaviorally based cognitive skills program. However, nothing is known about the postdischarge behavior of psychiatric patients who participated in such programs while receiving usual clinical treatment. The principal purpose of this article is to provide such information. Specifically, we will provide data on follow-up and patient outcomes in terms of rearrest, rehospitalization, and continued tenure in the community; demographic, clinical, and psychological correlates of outcomes; and behavior after discharge and outcomes.

Methods

Participants

A total of 181 of the center's patients were admitted to STAIR after April 1, 1997, and were discharged or transferred by October 31, 2001. Ninety of these patients successfully completed the program. Five of these patients had completed less than six months of outpatient follow-up as of May 5, 2002, the endpoint for participant inclusion. Thus the sample in the study reported here consisted of 85 patients who successfully completed the STAIR treatment program, were discharged to the community, and completed a minimum of six months of follow-up. As of May 5, 2002, eight patients from the original group of 85 had been lost to follow-up. Thus complete follow-up data were available for 76 patients (89 percent of the sample).

The study used data obtained during the course of the clinical evaluation of the STAIR patients. All data were gleaned through review of the patients' clinical records. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Manhattan Psychiatric Center and the institutional review board of New York State Office of Mental Health. As noted above, informed consent was waived. The criteria for the waiver of consent included the fact that the research involved no more than minimal risk to participants, that the waiver or alteration would not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the participants, and that the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver or alteration—at the time of the study, some of the patients were no longer available to provide informed consent (because of incarceration or the lack of compliance with the outpatient treatment); excluding the group of unavailable patients would have selectively biased the study sample.

Procedure

A battery of psychological tests was administered to every entrant to STAIR as part of the initial clinical evaluation. Data on intellectual functioning as measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) (20) or the Beta-II (21) were available for 66 clients.Psychopathy data, as assessed by the Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV) (22), were available for 75 patients.

Monthly reports were obtained for each STAIR patient who was discharged into the community by the case managers. These data included information about adherence to outpatient treatment, substance use or abuse, inpatient psychiatric readmissions, postdischarge arrests, and violent behaviors.This information constituted the follow-up data.

Data analysis

On the basis of the follow-up data, patients were classified into three mutually exclusive groups: stable (patients who maintained psychiatric stability and who had no arrests or hospitalizations), rehospitalized (those who experienced psychiatric relapse), and arrested or rearrested (those with criminal recidivism). The patients who were hospitalized and arrested (at different times) were assigned to the arrested group. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the three groups on continuous explanatory variables, and chi square analysis was used for categorical variables.Post hoc pairwise group comparisons were conducted if the overall analysis yielded a significant result. The data were analyzed with SAS. One-way analysis of variance was performed by using the general linear model (GLM) procedure.

Results

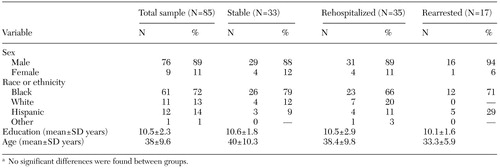

The duration of follow-up ranged from six months to four years. The mean±SD duration of the follow-up period for each group was 548±316 days in the stable group, 656±264 days in the rehospitalized group, and 701±247 days in the rearrested group. The difference in duration among the three groups was not statistically significant. As can be seen from Table 1, of the total sample of 85 participants, 33 were stable, 35 were rehospitalized, and 17 were arrested.

Demographic characteristics

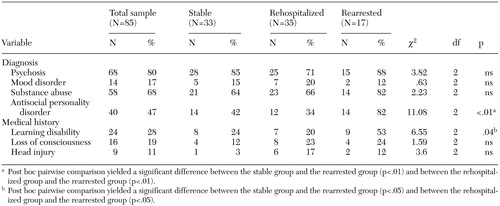

None of the demographic variables significantly discriminated the three groups (Table 1). A diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder and a history of learning disability significantly differentiated the rearrested group from the other two groups (Table 2).

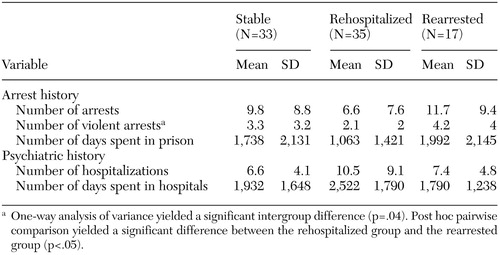

Patients who were not rearrested after discharge into the community had fewer arrests for violent offenses before STAIR treatment than those who were rearrested after discharge (Table 3).

Psychological measures

Patients who were rearrested attained significantly higher total scores on the PCL:SV than the other two groups (19.2±2.9, compared with 16.1±3.5 in the rehospitalized group and 15±4.4 in the stable group; F= 6.12, df=2, 72, p<.01). Possible scores range from 0 to 24, with scores of 18 or more indicative of psychopathy (22).Scores for this measure were available for 75 patients (88 percent). IQ did not significantly differentiate the three groups.

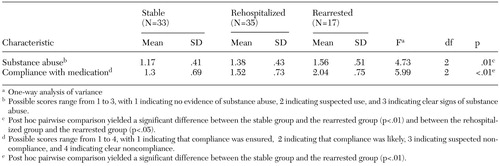

Substance abuse in the follow-up period

Substance abuse was graded on a 3-point scale on which 1 indicated no evidence of substance abuse, 2 indicated suspected use, and 3 indicated clear signs of substance abuse. The average score was calculated for each patient over the follow-up period. Use of substances significantly differentiated the groups such that both the stable group and the rehospitalized group had lower use and the rearrested group had the highest use (Table 4).

Compliance with treatment in the follow-up period

Compliance with medication treatment was graded on a 4-point scale on which1 indicated that compliance was ensured,2 indicated that compliance was likely, 3 indicated suspected noncompliance, and 4 indicated clear noncompliance. The average score was calculated for each patient over the follow-up period (Table 4). The rearrested group had the greatest noncompliance, which significantly differentiated the groups.

Of the 35 patients who were rehospitalized, 19 (54 percent) were rehospitalized more than once.A majority of the patients in this group were rehospitalized two times, but one patient was rehospitalized seven times. Eleven patients were hospitalized for periods exceeding one month.

Discussion

Preliminary findings for 85 patients who were discharged to the community after successfully completing a novel cognitive-behavioral treatment program indicate that after six months to four years in the community, 33 patients (39 percent) remained stable in the community (no rehospitalizations or rearrests). Thirty-five patients (41 percent) were rehospitalized at some point after discharge. Twenty-four patients (69 percent) were readmitted for short inpatient stays, whereas only 11 patients (31 percent) were readmitted for long-term treatment efforts.

Only 17 patients (20 percent) were rearrested. Of this subgroup, five (29 percent) were arrested for a violent crime, such as arson, assault, or robbery.The remaining 12 (71 percent) were arrested for drug-related or minor, nonviolent offenses. This finding compares favorably with the rearrest rates in general offender populations as well as with the rates for mentally ill offenders reported elsewhere (3,4,5). Consistent with many previous research findings, high psychopathy scores significantly predicted whether the patient was in the stable group, the rehospitalized group, or the rearrested group (23). Patients in the stable group had the lowest scores on the PCL:SV, whereas those in the rearrested group had the highest scores. Similarly, a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, which was highly correlated with the finding of psychopathy, was associated with group membership. The relationship between learning disability and arrest is consistent with Finnish data linking poor educational attainment and poor attentiveness at school with risk of criminal offense in adulthood among patients with schizophrenia (24). Now that the validity of the predictors has been established, it seems reasonable to develop a differentiated postdischarge follow-up program that would focus on the patients at the highest risk of arrest and rehospitalization, applying scarce resources in proportion to the risk.

Substance abuse after discharge also differentiated the three groups.Patients in the rearrested group were more likely to abuse substances than were those in the rehospitalized group, who in turn were more likely to abuse substances than those in the stable group. However, this differentiating effect of substance abuse disappeared when substance abuse was introduced as an independent variable together with full-scale IQ, total score on the PCL:SV, and compliance with medications.

Consistent with previous findings, lack of compliance with outpatient psychopharmacologic treatment was associated with rehospitalization and rearrest. The effect of noncompliance was independent of patients' IQ and of whether they abused drugs. This finding points to a possible antirecidivism effect of antipsychotic maintenance treatment on criminal behavior among patients with schizophrenia who are at risk of criminal behavior.

It was not surprising that IQ did not differentiate the three follow-up groups. Patients who completed the program had a higher full-scale IQ than those who were not able to complete the program for successful community discharge (unpublished data), resulting in little variance in IQ scores in the follow-up cohort. Neuropsychologic measures that tap executive functions of anticipation and planning as well as the ability to benefit from feedback in goal accomplishment may demonstrate more significant relationships.

This study had several limitations. The sample was small, so the findings pertaining to the rearrested group must be interpreted with caution. In addition, not all participants could be rated on all variables. Furthermore, the subsample that completed the STAIR program comprised patients who had better cognitive abilities and fewer impulsive behavioral problems than those who were terminated from the program and transferred to other wards rather than being discharged to the community. This selection factor may have contributed to the relatively low rearrest rates in this study compared with other studies. These selection biases limit the ability to generalize our results to other populations.

The interpretation of our results is further complicated by the lack of a control group of similar patients who did not participate in the STAIR program and were discharged.The classification of patients into three outcome groups—stable, rehospitalized, and rearrested—may have been affected by differences among the groups in the duration of the follow-up. Although the differences were not statistically significant, the stable group had a shorter duration of follow-up than the other groups. It is conceivable that the stable patients would have decompensated or committed new offenses with a longer follow-up. This problem will be easier to address when we continue the planned follow-up for each patient for five years after discharge from the STAIR program. The findings that we report here will be updated in a future article.

Conclusions

We adapted a cognitive-behavioral treatment program, originally designed for prisoners, and administered it to a sample of inpatients with major mental illness and a history of recidivistic aggression, crime, or both. Approximately 50 percent of these severely ill patients were able to successfully complete the program, which lasted eight to 12 months, and be discharged. The rearrest rate was lower than that observed in similar populations. Not surprisingly, psychopathy, history of violent crime, and history of learning disability were associated with rearrest and rehospitalization. Substance abuse and nonadherence to treatment after discharge led, predictably, to rearrest or rehospitalization.

Although our data cannot be used to rigorously evaluate the STAIR program, it is important to see the STAIR program and the data we present in the context of the current lack of effective therapeutic options for these extremely challenging patients. The usual management that consists of admitting these patients for several weeks of treatment that is largely limited to pharmacotherapy is clearly incapable of breaking the cycle of violence and rearrest or rehospitalization. The data we present suggest that long-term inpatient programs such as STAIR may be helpful to at least some of these patients. We hope that our data will inspire more rigorous studies of the effectiveness of STAIR or similar programs.

Dr. Kunz is affiliated with the Huntington Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia, and with Marshall University School of Medicine in Huntington. Dr. Yates, Dr. Czobor, and Dr. Volavka are with the clinical division of the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research in Orangeburg, New York. Mr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Lindenmayer are with the Manhattan Pscyhiatric Center in Ward's Island Complex, New York. Dr. Yates, Dr. Volavka, and Dr. Lindenmayer are also affiliated with the department of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine in New York City. Send correspondence to Dr. Yates at Manhattan Psychiatric Center, Ward's Island Complex, New York 10035 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of a sample of psychiatric patients with histories of aggression and crimea

a No significant differences were found between groups.

|

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of a sample of psychiatric patients with histories of aggression and crime

|

Table 3. Arrest and hospitalization data for a sample of 85 psychiatric patients with histories of aggression and crime

|

Table 4. Substance abuse and compliance with treatment during follow-up (six months to four years) in a sample of 85 psychiatric patients with histories of aggression and crime

1. Volavka J: Neurobiology of Violence, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002Google Scholar

2. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al: Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1112–1115, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Harris V, Koepsell TD: Criminal recidivism in mentally ill offenders: a pilot study. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 24:177–186, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ventura LA, Cassel CA, Jacoby JE, et al: Case management and recidivism of mentally ill persons released from jail. Psychiatric Services 49:1330–1337, 1998Link, Google Scholar

5. Feder L: A comparison of the community adjustment of the mentally ill offenders with those from the general prison population. Law and Human Behavior 15:477–493, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Rotter M, Steinbacher M, Massaro J, et al: The clinical impact of doing time, in Innovations in Forensic Mental Health: Working With the Mentally Ill Offender. Edited by Landsberg L, Smiley A. Kingston, NY, Civic Research Institute, 2001Google Scholar

7. Fabiano EA, Porporino FJ, Robinson D: Canada's cognitive skills program corrects offenders' faulty thinking. Corrections Today 53:102–108, 1991Google Scholar

8. Ross R, Fabiano E: Time to Think: A Cognitive Model of Delinquency Prevention and Offender Rehabilitation. Ottawa, Canada, T3 Associates Training and Consulting, 1985Google Scholar

9. Robinson D: The Impact of Cognitive Skills Training on Post-Release Recidivism Among Canadian Federal Offenders. Research report R-41. Ottawa, Canada, Correctional Research and Development. Correctional Service, 1995Google Scholar

10. Johnson DAW, Pasterski G, Ludlow JM, et al: The discontinuance of maintenance neuroleptic therapy in chronic schizophrenic patients: drug and social consequences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 67:339–352, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and non-adherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:226–231, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Swanson J, Swartz M, Estroff S, et al: Psychiatric impairment, social contact, and violent behavior: evidence from a study of outpatient-committed persons with severe mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S86-S94, 1998Google Scholar

13. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Felthous AR: Childhood antecedents of aggressive behaviors in male psychiatric patients. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 8:104–110, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hodgins S: Mental disorder, intellectual deficiency, and crime: evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:476–483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Martell DA, Dietz PE: Mentally disordered offenders who push or attempt to push victims onto subway tracks in New York City. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:472–475, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Dayson D, Gooch C, Thornicroft G: The TAPS project:16. difficult to place, long term psychiatric patients: risk factors for failure to resettle long stay patients in community facilities. British Medical Journal 305:993–995, 1992Google Scholar

18. Klassen D, O'Connor WA: Assessing the risk of violence in released mental patients: a cross-validation study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1:75–81, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Tengstrom A, Grann M, Langstrom N, et al: Psychopathy (PCL-R) as a predictor of violent recidivism among criminal offenders with schizophrenia. Law and Human Behavior 24:45–58, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1981Google Scholar

21. Kellog CE, Morton NW: Revised Beta Examination-Second Edition Manual (Beta II). New York, Psychological Corp, 1974Google Scholar

22. Hart SD, Cox DN, Hare RD: The Hare PCL:SV Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version Manual. Toronto, Canada, Multi-Health Systems, 1995Google Scholar

23. Hart SD, Hare RD, Forth AE: Psychopathy as a risk marker for violence: development and validation of a screening version of the revised psychopathy checklist, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

24. Cannon M, Huttunen MO, Tanskanen AJ, et al: Perinatal and childhood risk factors for later criminality and violence in schizophrenia: longitudinal, population-based study. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:496–501, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar