Two-Year Evaluation of the Logic Model for Developing a Psycho-Oncology Service

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to test whether reorganizing a psycho-oncology service in a planned and focused manner would maximize the achievement of coherent developmental goals. METHODS: The logic model, a strategic program development tool, was used in the context of a public psychiatry fellowship to analyze and plan the organizational objectives of a psycho-oncology service. To assess the efficacy of the logic model, a two-year prospective evaluation of the model's outcome measures was performed. RESULTS: The psycho-oncology service was systematically reorganized through use of the logic model. Qualitative and quantitative data identified the degree of goal achievement. Most of the short- and medium-term clinical, educational, and research goals, as measured by outcome measures, had been realized at the two-year point. CONCLUSIONS: The logic model facilitated the effective reorganization of a psycho-oncology program by analyzing the existing service, developing pertinent goals, and then measuring goal attainment. These findings will be useful to psychiatric services interested in rational program development and service delivery, especially in small and medium hospitals with limited resources.

Psychiatric services are often fragmented and uncoordinated (1) and may develop in response to immediate clinical needs and the vicissitudes of short-term budgets. This article describes how the psycho-oncology service at Long Island Jewish Medical Center was reorganized with use of a logic model to enable coherent programmatic development.

The psycho-oncology service was started in 1993 with a half-time psychiatrist by a joint initiative of the medical oncology and psychiatry departments. Three problems emerged. First, the position was funded by medical oncology. As a consequence, the psychiatrist saw only medical oncology patients. Because the hospital lacked a comprehensive cancer center model, cancer patients who were receiving treatment from the departments of gynecology, urology, surgery, or radiation oncology or from community oncologists did not have access to the full spectrum of psycho-oncology care. In addition, social workers, psychologists, case managers, nurses, and pastoral care workers were not organized as a multidisciplinary psycho-oncology team and received no specific training for working with cancer patients. Finally, when the psychiatrist who founded the program left the institution, the program, lacking a coherent structure and clearly articulated goals, had its funding reduced and its scope severely diminished.

Against this background, we were asked to revitalize the psycho-oncology service and were given one full-time position for a consultation-liaison psychiatrist (the first author). This development led us to ask what would be the best way to deliver adequate psycho-oncology care to a medium-sized metropolitan hospital. We believed that, in addition to psychiatric care, it was important to build a comprehensive, accessible psychosocial program that truly served the community, provided psycho-oncology training for medical professionals, and had a robust research agenda. In 2001 we set about achieving the reorganization of the medical center's psycho-oncology program by using the logic model within the framework of a public psychiatry fellowship.

The public psychiatry fellowship

The public psychiatry fellowship, a partnership of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, aims to facilitate the training of high-caliber early-career psychiatrists in the public sector. Eighty percent of the fellowship's alumni have academic appointments (2).

Fellows spend three days a week working in a public mental health organization and two days a week in the classroom. Typically, fellows continue at their workplace on a permanent basis after completion of the fellowship year. In our case, the first author, a consultation-liaison psychiatrist, continued on as the head of psycho-oncology after he graduated from the fellowship.

The logic model

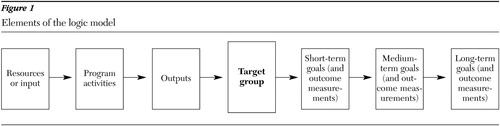

The logic model is a widely accepted program development tool that has been implemented in a variety of settings, including in the Office of National Drug Control Policy in the White House (3), by United Way (1), and by numerous university, government, educational, and social agencies (4,5,6,7). The model makes explicit the logic of how a program achieves its objectives and goals (8). Briefly, the model focuses on a program's particular population, or target group—for example, patients or clients. The model explores the effect of the current state of the program—in terms of resources, program activities, and outputs—on the target group and enables production of a blueprint for future development, expressed as short-term, medium-term, and long-term goals, with corresponding outcome measures. This blueprint is the core of the logic model. The model recognizes the need to understand key contextual factors that are external to the program's direct sphere of influence and to take these factors into account. The elements of the logic model are depicted in Figure 1.

The logic model has three important strengths. First, the graphic simulation of a program (3) enables key elements to be portrayed on a single piece of paper. Thus priorities and interactions can be easily identified without becoming buried in detail. Second, a particularly powerful effect is created if logic models are used at multiple levels within an organization (3,8): different branches of the organization can speak the same language, thus facilitating cooperation in goal attainment and measurement of performance. Third, the model identifies end points and measures performance. Thus targets are clearly identified and, because goal attainment is constantly being measured, identification and correction are easily achievable if the program strays off course.

Methods

We constructed a logic model by using the following five steps.

Collecting relevant information

The collection of relevant information involves obtaining key data from multiple sources, such as interviews with stakeholders and review of previous evaluations, annual reports, budgets, and tables of organization as well as the relevant literature. Key figures at Long Island Jewish Medical Center were interviewed, and a history of the department was formulated. Although the direct resources of the psycho-oncology program were limited to one salary line, a large number of preexisting staff resources were identified within the hospital. The consultation-psychiatry chief and fellowship director, the public psychiatry fellowship supervisor, and the oncology social workers all had substantial experience in psycho-oncology and program development. Furthermore, the chief of oncology was an advocate for the integration of psychiatric care into oncology practice. The needs assessment and interviewing of key stakeholders was conducted over a period of three weeks.

Clearly defining problems and their contexts

Clearly defining problems and their contexts enables clarification of the need for the program and analysis of the problems faced by service recipients and stakeholders. As many as 48 percent of cancer patients have a DSM diagnosis (9). Without psychological tools, the task of dealing with cancer can be overwhelming to patients, their family members, and clinicians.

We identified seven major programmatic problems. First, because the hospital lacked a comprehensive cancer center, delivery of oncology services was fragmented and constrained by the existence of multiple autonomous departments, such as surgery, neurosurgery, gynecology, urology, radiation oncology, and medical oncology. Psychiatric care was centered on medical oncology, the funder of the psycho-oncology initiative. Second, limited psycho-oncology services were available at the medical center's five affiliated hospitals.

Third, no method existed for coordinating multidisciplinary psycho-oncology care between psychiatrists, social workers, psychologists, case managers, and community agencies. Fourth, there was no advocate for psycho-oncology in the health system. Fifth, limited psycho-oncology training was available to multidisciplinary clinicians. Sixth, services were severely diminished when the founding psychiatrist left the institution. Finally, psycho-oncology did not appear on the table of organization, there was no job description, and goals had never been articulated.

Defining the elements of the model

An intermediate step is to define the elements of the logic model. Information is categorized into a table representing all the elements of the model. For the sake of brevity, this step is not elaborated upon here.

Drawing the model

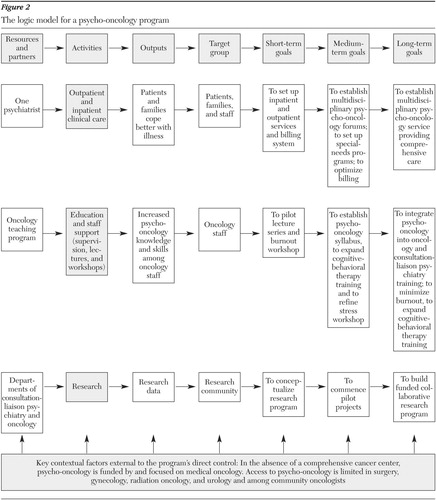

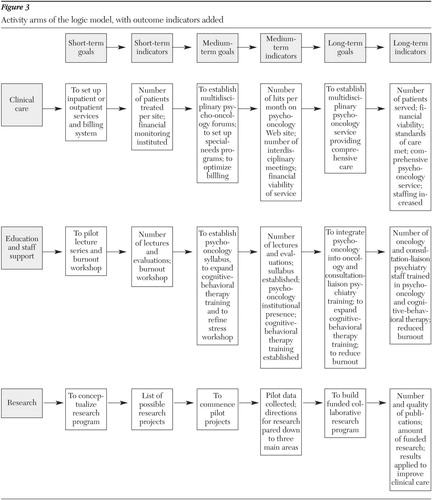

When drawn, the logic model is a simplified, graphical representation of the proposed program narrative, which shows the logical linkages between resources, program activities, outputs, and goals, depicted in Figure 2 (8). In the interests of avoiding confusion, only three to five "activities" should be portrayed. The figure represents a global blueprint for the psycho-oncology program. A more detailed logic model blueprint was built for each of the "activity" arms of the program—clinical, education, and research—and incorporates measures of performance and goal achievement. This stage, depicted in Figure 3, took three weeks.

Verifying the model with stakeholders

The fifth and final step is to verify the logic model with stakeholders. The model needs to be continuously evaluated by core stakeholders for accuracy of programmatic analysis, logical flow of elements, and understanding of external contextual factors. Are there other ways in which the goals can be achieved? (8). If so, these options should be explored. A timeframe needs to be defined. Feedback from oncology, consultation-liaison psychiatry, faculty from the public psychiatry fellowship, and key clinicians and administrators facilitated refinement of the model. We defined short-term, medium-term, and long-term goals as those to be achieved within one year, one to two years, and three to five years, respectively.

Results

After two years we analyzed the achievement of short- and medium-term goals as measured by quantitative and qualitative indicators for clinical care, education, and research as set out in the logic model.

Clinical care

Achievement of short-term goals. Psychiatric rounds were restarted on the oncology ward, and outpatient services were launched at an off-site clinic. A stem-cell-transplant program was inaugurated. The number of patient contacts increased from 276 in 1999 (under the previous psychiatrist) to 282 in 2001-2002 (under the current psychiatrist).

A psychiatric billing system was set up in the challenging environment of oncology billing. The amount of money collected in oncology was compared with that collected in consultation-liaison psychiatry, which uses the same billing codes. In 2002, psycho-oncology collected $76 per inpatient contact and consultation-liaison psychiatry collected $89, a difference of 15 percent. Regular monthly billing meetings were established. Two billing problems were identified. First, joining insurance panels was difficult and time-consuming. Second, the "collection rate"—the amount billed divided by the amount collected—was an inaccurate outcome measure, because capitated agreements render the amount billed meaningless. The lack of a suitable replacement measure remains an ongoing problem in monitoring billing.

Achievement of medium-term goals. Outpatient psychiatric services were relocated into the oncology clinic, which allowed for greater integration of psycho-oncology into routine cancer care. This development was a powerful symbol of the importance of psycho-oncology to the oncology department.

The number of inpatient contacts increased by 13 percent in the second year, to 324. However, the number of outpatient contacts (adjusted to account for differences in working hours per week) declined by 10 percent, to 370. One probable reason for this decline was the increased time spent on program development and administration. In terms of billing, income collected was maintained.

A weekly psychosocial interdisciplinary meeting successfully identified patients and families with psychosocial needs. For example, a dying mother who had no advance directives, along with her overwhelmed children, required palliative care, social work, and psychiatric interventions. After the patient's death, the family was offered bereavement services. Monthly meetings with oncology, consultation-liaison psychiatry, and the cancer care quality-improvement committee helped create an institutional presence for psycho-oncology.

In addition, we inaugurated a psycho-oncology Web site that lists resources within the hospital and in the community, support groups, recommended reading, and bereavement services. The Web site had 705 hits during its first month of operation and thereafter averaged 243 hits a month. The site identified nine cancer support groups in the hospital and had a systemwide impact in raising awareness of psycho-oncology.

Achievement of long-term goals. A comprehensive plan for expanding psycho-oncology was constructed ahead of schedule (after 18 months). The plan was endorsed by key stakeholders and currently awaits final budgetary approval.

Education and staff support

Achievement of short-term goals. Four lectures were given to residents, fellows, and social workers on psychiatric issues among cancer patients, managing "difficult" patients, and treatment of fatigue. Evaluations based on a Likert scale averaged 4 out of 5.

In addition, a five-session pilot cognitive-behavioral therapy burnout workshop was designed to ameliorate perceived staff stress. Data generated were used to refine the intervention.

Achievement of medium-term goals. Ten lectures were delivered on topics such as pain management, antidepressants, and the management of delirium among cancer patients, as well as a grand rounds presentation on the importance of cognitive-behavioral therapy to oncologists. This program represented an increase in the number of lectures of 157 percent over the previous year.

In addition, a syllabus was designed and implemented in the format of a ten-hour continuing medical education accredited seminar covering topics such as psychopharmacology, delirium, the family and cancer, culture and cancer, pain, bereavement, and communication. One-third of the workshops were led by the first author, and the remainder were led by other hospital-based cancer experts.

A seven-hour workshop focusing on cognitive-behavioral therapy among persons with mental illness was presented to psychiatrists, residents, and social workers. Three consultation-liaison fellows received weekly supervision in three-month blocks. One of the fellows received grant funding to attend a train-the-trainer program at the Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy. Funding was secured to send a second fellow to the program this academic year.

Research and academic activities

Achievement of short-term goals. By brainstorming research directions, we identified three areas of potential research: cognitive-behavioral therapy with cancer patients, collaborative research on quality-of-life issues, and psycho-oncological aspects of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Achievement of medium-term goals. Funding was secured for a visiting professorship for a leading Scottish expert that will focus on building the foundations of a cognitive-behavioral research program with cancer patients. In addition, the first author was appointed to the cancer and lymphoma group B's quality-of-life subcommittee. This national group engages in phase III collaborative research. The first author also joined a new hospital-based chronic lymphocytic leukemia research consortium. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, one of the last incurable malignancies, has not been closely studied by psycho-oncology. A part-time research assistant was secured for this project.

Finally, an article about why patients refuse chemotherapy was coauthored and submitted for journal publication. A poster about the delivery of psycho-oncology care was presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine.

Discussion and conclusions

The logic model was used to plan and implement a three- to five-year blueprint for a comprehensive psycho-oncology program in a medium-sized metropolitan hospital. Evaluation of two-year goal attainment with use of prespecified qualitative and quantitative indicators was consistent with the predictions of the logic model.

Measurement of goal attainment is a central tenet of the logic model. Given that evaluation is costly and time-consuming, only relevant data should be collected (4). Measuring effectiveness must be carefully timed, because early evaluation may miss an effect, and late evaluation may result in prolongation of ineffectual processes.

Choosing outcome indicators is difficult, and we found this to be a major challenge of the logic model. Smith (10) reviewed some commonly used psychiatric process measures, such as percentage of direct service time delivered by staff, functional status, attendance, length of stay, and time on waiting lists. However, we were not able to use these measures in our model. Instead, we tried to tailor measures that we believed were directly relevant to our program, because the logic model emphasizes the minimization of meaningless data or noncollection of relevant data. For example, quality-of-life measures, which are important to psycho-oncology research, were not used, because they were peripheral to the stated short- and medium-term goals of our specific logic model.

We attempted to track financial indicators, such as the number of bills rejected by insurance companies or sent to the collections department, which allowed for the detection of many billing problems that otherwise may have gone unnoticed. A common problem was incorrect coding. Seeking preapprovals for patients was time-consuming, as was joining insurance panels. Although we endeavored to provide psycho-oncology care for all cancer patients, third-party-payer bureaucracy was a rate-limiting factor.

Finding a financial indicator that reflected the "bottom line" also proved difficult. The hospital used the measure "collection rate," defined as the amount billed divided by the amount collected. This method does not factor in capitation agreements with insurance companies, and we considered it to be a blunt measure of billing and collection efficacy. We are currently trying to develop more sophisticated measures of financial viability as our program continues to grow in complexity.

In monetary terms, the logic model was economical. We built a psycho-oncology program for the cost of one psychiatrist minus income generated from that position ($50,000 in the first year of operation).

The cost of delivering psychiatric care is a vital element in implementing new psychiatric services, especially in the current environment of complex third-party reimbursement procedures. Although we annually billed $180,000 in services, only $50,000 was collected. We did not expect financial independence in the first three to five years of start-up. However, this is an area that warrants careful attention by other institutions using this model for program development.

Because of our limited resources and in order to prevent duplication of services, it was essential to identify preexisting partners who could be co-opted to achieve the goals of psycho-oncology. These include oncologists, nurses, social workers, administrators (who want to retain satisfied customers by offering comprehensive services), and oncology chiefs (who must satisfy psychosocial certification requirements dictated by the American College of Surgeons). Joint accountability portrayed via a logic model can increase the attainment of end points, helping stakeholders to work together, achieve consensus, and speak the same language (3). Ultimately many elements account for easing the psychosocial burden of cancer.

The multidisciplinary delivery of psycho-oncology care in a cancer center is the model advocated by Jimmie C. Holland in her seminal text (11). However, many smaller and medium- sized hospitals, including Long Island Jewish Medical Center, lack comprehensive cancer centers, which presents a challenge to the delivery of cohesive psycho-oncology services. The traditional consultation-liaison psychiatry model involves either an expert consultant who is called in to assist with a difficult case or a psychiatric liaison for a particular unit who is not necessarily part of that department (12). The difficulties here are rational program development and coordination of multidisciplinary care in the absence of a cohesive management framework.

Traditional program evaluation models are often designed to assess system inputs followed by system outputs. For example, the public psychiatry fellowship teaches another model of program evaluation—the congruence model—that works in this exact way (13). Millar and associates (3) point out that this approach fosters defense of the status quo and hence recommend starting to build a logic model with goals, or "what needs to be done," rather than what is being done. This approach prevents programs being built as safety nets that bolster the preexisting program, which may be intrinsically flawed (1).

By identifying factors external to our program's control, the logic model identified a major structural incongruence that impeded attainment of long-term psycho-oncology goals: a medical oncology funding line prevented the expansion of psycho-oncology services to other departments and sites. As a result, we invested considerable resources into building an expansion plan that addressed how the psycho-oncology program can be funded and delivered to diverse clinical sites. This plan will be the focus of long-term program development.

One possible pitfall of the logic model is that evaluators may see it as an overtly rigid plan and assume that compliance with the model is an indicator of quality (4). Feedback from outcome measures should be used to further shape the model in situ. A further theoretical weakness is that, as far as our research indicated, the model's efficacy has never been demonstrated in a controlled trial.

We hope that planners of psychiatric services, especially in smaller community hospitals, as well as early-career psychiatrists who are trying to develop new programs will find the logic model helpful. On the basis of the success of its psycho-oncology program, Long Island Jewish Medical Center is also using a multilayered logic model to drive its chronic lymphocytic leukemia research program.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kanti Rai, M.D., for his guidance and support of this project from its inception.

Dr. Levin heads the psycho-oncology program of Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 270-05 76th Avenue, New Hyde Park, New York 11040 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Weiner and Dr. Saravay are consultation-liaison psychiatrists at the medical center. Dr. Deakins is associate director with Columbia University's public psychiatry fellowship.

Figure 1. Elements of the logic model

Figure 2. The logic model for a psycho-oncology program

Figure 3. Activity arms of the logic model, with outcome indicators added

1. Julian DA: The utilization of the logic model as a system level planning and evaluation device. Education and Program Planning 20:251–257, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Ranz J, Rosenheck S, Deakins S: Columbia University's fellowship in public psychiatry. Psychiatric Services 47:512–516, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Millar A, Simeone RS, Carnevale JT: Logic models: a systems tool for performance management. Evaluation and Program Planning 24:73–81, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Cooksy LJ, Paige G, Kelly PA: The program logic model as an integrative framework for a multi-method evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning 24:119–128, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Dwyer JJM, Makin S: Using a program logic model that focuses on performance measurement to develop a program. Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique 88:421–425, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

6. Harty H: Measuring program outcomes: a practical approach. Washington, DC, United Way of America, 1996Google Scholar

7. Israel GD: Using Logic Models for Program Development. Document AEC 360. Gainesville, University of Florida, Program Development and Evaluation Center, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 2001Google Scholar

8. McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB: Logic models: a tool for telling your program's performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning 22:65–72, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 248:751–757, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Smith ME: A guide to the use of simple process measures. Evaluation and Program Planning 10:219–225, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Holland JC: Establishing a psycho-oncology unit in a cancer center, in Psycho-oncology. Edited by Holland JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

12. Cassem NH, Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF (eds): Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. St Louis, Mosby, 1997Google Scholar

13. Nadler DA, Tushman ML: A congruence model for diagnosing organizational behavior, in Organizational Psychology: A Book of Readings, 3rd ed. Edited by Kolb D, Rubin I, McIntyre J. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1979Google Scholar