Bereavement in the Context of Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether the situational factors that contribute to severe grief in the general population predicted the severity of grief in a sample of persons who had diagnoses of serious mental illness. METHOD: Research participants who had a diagnosis of a serious mental illness and who reported the death of a close friend or family member during a five-year service evaluation project were asked to detail the circumstances that surrounded the death and to rate how the death affected their lives. Key research measures included the self-rated measurement of the impact of the death, the self-rated measurement of the duration of the reported grief, and scores on a psychiatric symptom assessment in the six months after the death. A regression analysis tested the cumulative count of four situational factors—residing with the close friend or family member at the time of the death, the suddenness of the death, having low social support, and having concurrent stressors—as a predictor of severe and prolonged grief. RESULTS: In the sample of 148 individuals with serious mental illness, 33 (22 percent) reported the death of a close friend or family member as a significant life event that resulted in relatively acute and brief grief (15 individuals, or 10 percent) or severe and prolonged grief (18 individuals, or 12 percent). The regression analysis confirmed that the more situational factors that occurred at the time of the death, the more severe the grief reaction was, irrespective of psychiatric symptomatology. CONCLUSIONS: Mental health services for persons with serious mental illness should begin to incorporate preparation for parental death and bereavement counseling as essential services, and such interventions should approach bereavement as a normal rather than a pathological response to interpersonal loss.

Severe grief in response to the death of a close friend or family member is associated with a variety of physical and mental disorders (1,2,3) as well as with persistent depressive symptoms (4,5). Although the estimated incidence of prolonged, intense grief in the general population is only 11 to 15 percent (6,7,8), a study found that nearly a third of the psychiatric outpatients who were surveyed were currently experiencing intense grief that had already lasted an average of ten years (9).

A bereaved individual with a preexisting psychiatric disorder is especially vulnerable to depression and depression-related physical illnesses (10,11). However, the etiology of chronic, severe grief appears to be more circumstantial than psychiatric in nature. Maladaptive cognitions—for example, denial, self-blame, and ambivalence—do not appear to lengthen the grieving process (12,13,14,15), but situational factors do. Circumstances that predict prolonged grief include a strong dependence on the close friend or family member before the death, the suddenness of the death, a lack of social support, and co-occurring other stressors (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27). Co-occurring factors that can intensify grief or lengthen the time of grief include the concomitant loss of health or financial security, forced relocation, the sacrifice of a job to care for the dying person, or the burden of dealing with legal and practical problems related to the death (28,29,30). The loss of a close friend or relative may set in motion a cascade of negative events that culminate in serious physical illness (31) or even homelessness (32). As a whole, situational factors outweigh psychological factors in predicting prolonged, intensified grief.

Our study explored the prevalence of prolonged, severe grief among adults with serious mental illness who were recruited from a midsized city in New England. We hypothesized that the same situational factors that contribute to chronic, severe grief among the general population would contribute to chronic, severe grief among persons with serious mental illness, more so than the mental illness itself. Because we believe that interpersonal loss is best understood from a personal perspective (33,34), we studied retrospective accounts of 33 bereaved individuals, measuring the impact of death events in the context of other life events and engagement in mental health services.

Methods

Study sample

The research sample was taken from a project that was approved by the institutional review board of Fountain House in New York City, in which participants had been randomly assigned to either an assertive community treatment program (35) or a certified clubhouse program (36). The project was conducted from 1995 to 2000. The subsample used for this retrospective analysis included every participant who had interview data through the 24-month point of service (148 of 177 participants). This subsample was comparable to the total sample on all background characteristics and was similar to most population descriptions of persons with serious mental illness: 90 percent (N=133) were taking psychiatric medication, 80 percent (N=118) were unmarried, 36 percent (N=53) had less than a high school education, and 74 percent (N=110) were unemployed for a year or longer. A total of 51 percent of our participants (N=76) were male, 22 percent (N=32) belonged to an ethnic minority group, 53 percent (N=79) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The mean±SD age at enrollment was 38±9.7 years.

Research measures

Self-reported feelings of grief. A variety of criteria distinguish severe grief from other psychiatric diagnoses, including whether the grief was traumatic, prolonged, chronic, or complicated by other losses (3,37,38,39,40). Because our study relied on spontaneous subjective reports from research participants rather than on assessments from clinicians, we used only the most unambiguous criteria for severe grief: severity and duration, which Enright and Marwit (41) proposed as the most defining features of severe grief.

At the end of the five-year research study, each participant was asked to review and augment a chart of life events that he or she had spontaneously reported in earlier research interviews. Participants were asked to rate how they were doing at the time of each life event relative to a baseline self-rating by using a Likert scale that ranged from 3, "much better," to -3, "much worse." Participants could score each life event listed on the temporal chart, or they could draw a timeline that depicted their ups and downs over the course of the five-year project in relation to the various life events. Event impact was coded as the rating (3 to −3) on the left axis that intersected by the hand-drawn line at the point that the event occurred. Grief severity was measured as the change in the global self-rating from the death event to the immediately preceding significant life event on each participant's retrospective timeline. If the death occurred before the participant entered the project (N=9), grief severity was measured by using the self-rating that was associated with the first timeline event described by the participant as being directly related to the death—for example, the loss of housing because of the recent death of a parent or spouse. A total of 33 participants reported the death of a close friend or family member; 28 of the 33 participants (85 percent) completed retrospective timelines that provided measures of the severity of their grief. These timelines were completed three to five years after the participants' baseline interviews (1,398±337 days; median of 1,456 days).

The operational measure of prolonged grief was the repetition in the participants' spontaneous reports of grief that lasted a year or longer—that is, self-reports of grief at two or more six-month interviews or self-ratings that remained 3 or more points lower than the participants' baseline score for a year or longer after the death event. A total of 26 of the 33 participants who had experienced the death of a close friend or family member (79 percent) had follow-up periods of a year or longer between the death and the final interview, which allowed a classification of their grief episode as either brief or prolonged.

When participants were dichotomized on the basis of self-rated severity of grief (a median change in score that was higher or lower than −3) and on the basis of the duration of the reported grief (a period of grief that was less than one year or a year or more) a perfect match was seen between the categories that show the duration of grief and the severity of grief for the 21 participants who had both types of data. All the participants who reported that their grief lasted a year or longer had a self-rating for the death event that was 3 or more points lower than the rating of their immediately preceding event. To retain all 33 participants for statistical analysis, a composite variable was created on the basis of the self-rated severity or the self-reported duration of grief. This coding classified 15 participants (45 percent) as having experienced acute and brief grief and 18 participants (55 percent) as having severe and prolonged grief.

To allow for the severity ratings of the death event that were recorded in the retrospective timelines to be used as a continuous variable, the five participants who did not have severity ratings—because of their refusal to be surveyed, their inability to be contacted, or their own death—were assigned a score on the basis of the duration of grief that was documented in earlier interviews. Participants who fell into the prolonged grief group (N=4) were assigned the median rating for the severe impact group (−3), whereas the one participant who reported grief on only a single occasion was assigned the median rating for the acute grief group (−1).

Psychiatric symptoms

The primary psychiatric diagnosis was derived from medical records that were dated before the death event. Psychiatric symptoms were measured by using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (42) during each biannual interview. Interviewers were trained by Lewis Opler, M.D., an author of the PANSS, and had high rates of interrater reliability for the three subscales: positive (r=.95), negative (r=.89), and general (r=.94).

Our rating of psychiatric symptoms for this study was the PANSS total score for the interview that immediately followed the death event. On average, this PANSS measurement was given three to four months after each death event (139±117 days; median of 100 days). Baseline PANSS scores were used for participants for whom the death event occurred before enrollment in the project.

Grief severity ratings appeared to be distinct from psychiatric symptoms. For the 24 participants who reported deaths that occurred during the project, no correlation was found between grief severity ratings and proximally measured PANSS psychiatric symptoms. In addition, the two groups that had different reactions to grief—acute and brief grief and severe and prolonged grief—did not differ significantly on their PANSS total scores after the death event (a score of 64.53±10.19 for participants who experienced acute and brief grief compared with 70.55±15.75 for participants who experienced severe and prolonged grief) on any of the three PANSS subscales.

Factors expected to influence grief duration

The four situational factors hypothesized to complicate grief were coded as dichotomous variables and were summed to obtain a total score that ranged from 0 to 4. The four variables included sharing a residence, that is, living in the home of the deceased at the time of the death; the suddenness of death, that is, the death event was unexpected or was attributed by the participant to suicide, drug overdose, accident, acute illness, or homicide; the lack of social support, that is, data collected before the death event indicated that the participant did not have anyone to rely on for emotional or instrumental support except for the close friend or family member; and the co-occurrence of other stressors, that is, a significant negative life event reported by the participant that occurred within a year preceding or following the death event.

Results

Prevalence of bereavement

Nearly a quarter of the 148 study participants (33 participants, or 22 percent) spontaneously reported the death of a close relative or friend during a research interview. The majority of these deaths (24 participants, or 73 percent) occurred in the six months preceding enrollment (N=3) or after enrollment (N=21). Death events that occurred during the project were evenly distributed across the five years that the project lasted (2.59±1 years; range of .5 to 4.5 years). This 16 percent death incidence rate—24 of 148 participants reported that a death event had occurred during the project period—over an average of four years of study participation is comparable to the 19 percent death incidence rate reported for a large nonpsychiatric sample of middle-aged adults in a study that covered a two-year retrospective span (43). The 33 individuals who reported a significant death event did not differ from the remaining 115 individuals in any background characteristics or in the total number of days in which there was any service contact with the assigned program.

Relationship to deceased

In keeping with the fact that the participants were largely middle aged or older, the deceased was most often a parent—that is, a mother (N=11) or father (N=10)—followed by a spouse or partner (N=5), sibling (N=5), or an adult child (N=2). Every participant who reported a death event recounted feelings of sorrow. Change in retrospective self-ratings from the significant life event that preceded the death to the death event ranged from −1 to −6 (−2.61±1.60; median of −3), with 55 percent (N=18) of the 33 participants reporting a decline of −3 points or less.

Factors unique to prolonged and severe grief

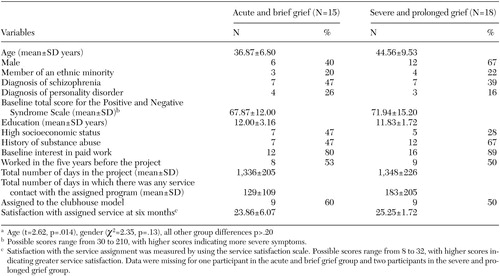

As Table 1 shows, the only variable in which the group with acute and brief grief and the group with severe and prolonged grief differed significantly was age. Participants with more severe grief tended to be older, although participants in both groups were primarily middle aged. The two groups were also comparable in terms of the time they had spent in the research project, the total number of days in which there was any service contact with the assigned program, and satisfaction with the psychiatric services they had received (44). Also, equivalent numbers of participants who experienced severe grief had been randomly assigned to an assertive community treatment program (N=9) and clubhouse services (N=9).

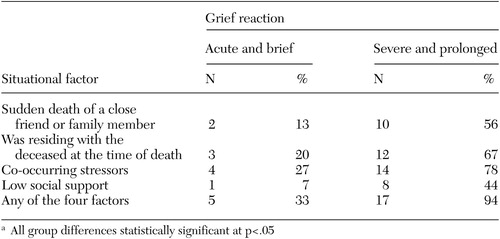

As can be seen in Table 2, each of the four situational factors had a strong association with the intensity and duration of grief. Individuals for whom any one of the four situational factors accompanied the timing of the death of a close friend or family member were significantly more likely to experience prolonged and severe grief rather than brief and acute grief (χ2=13.750, df=1, p<.001).

Although only two participants had to deal with all four extenuating factors, 90 percent of the participants (N=16) with severe and prolonged grief reported at least two complicating factors. Three of these factors—lack of social support, residing with the close friend or family member at the time of the death event, and co-occurring stressors—were closely intertwined, with pairings between any two of the three factors occurring equally often. Among participants with severe and prolonged grief, about half of those who reported any one of these three factors had also dealt with a sudden loss.

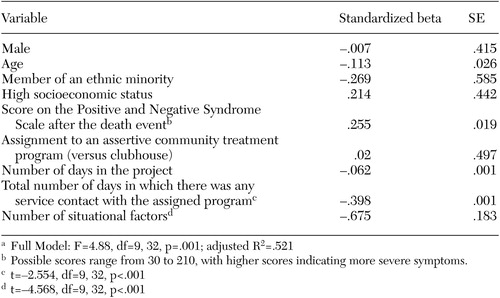

A cumulative count of 0 to 4 for the four situational factors that are known to escalate grief was used as a measure of the "pile up" of situational distress in each individual's life (33). This number of situational factors was entered as a predictor variable in a regression analysis that included as control covariates basic demographic variables and a dichotomous measure of socioeconomic status, with high socioeconomic status defined as having worked a white-collar or managerial job for more than five years or having a postsecondary education. Scores on the PANSS (42) administered during the research interview that followed each death event were also included to control for the role that psychiatric illness might play in aggravating or prolonging grief. Other covariates included whether the participant was assigned to an assertive community treatment program or to a clubhouse, the total number of days in which there was any service contact with the assigned program, and the length of time spent in the research project.

Table 3 shows that the full regression model containing all nine covariates was statistically significant and that the number of complicating situational factors and the total number of days in which there was any service contact with the assigned program were both statistically significant predictors of more severe grief, even when the analysis controlled for personal characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, and type of mental health services received. To explore the possibility that time between the death event and the retrospective task of reviewing the chart of life events could have influenced the participants' recollection of grief, we repeated the analysis, this time including the number of days between the death and the retrospective interview as a covariate for participants for whom we had this data (24 participants, or 73 percent). The timing of the retrospective task was not a significant predictor of how the death event affected the participant, and the level of service use was not statistically significant. However, the number of situational factors remained statistically significant (χ2= -.743, p<.01), as did the model as a whole (F=3.03, df=10, 22, p=.036; adjusted R2=.480).

Discussion

Limitations of the study include the small sample and reliance on participants' self-reports. Nevertheless, the sample's normative rate of reported bereavement and the close correspondence between self-reported measures of grief intensity and self-reported measures of the duration of grief provide confidence in the meaningfulness of the study findings. The results of the regression analysis suggest that the same situational factors that are predictive of more prolonged, severe grief in a general population further complicate and burden the lives of people with serious mental illness over and above the burden of psychiatric symptoms. It appears that even if grief is worse for someone who must also cope with psychiatric symptoms, the extent of any individual's personal grief depends primarily on accompanying situational stressors. Stressors that are usually considered psychological in nature, such as emotional dependence, may have situational determinants that are often ignored, such as social isolation or residing with the close friend or family member at the time of the death event. Persons with serious mental illness could benefit from knowing that grief is a normal reaction to the loss of a loved one and to cumulative life stress and not necessarily a reflection of their emotional fragility.

The correlation that we found between grief severity and more frequent service contact suggests that individuals with serious mental illness already turn to their service providers when facing bereavement. Because the majority of individuals with serious mental illness are middle aged and have aging parents, it seems imperative that service programs begin to offer practical planning for bereavement as an essential service; this planning can include counseling, help with funeral arrangements, financial planning, or arranging for a move to supported housing (45,46,47,48). A closer look at the participants who experienced the death of a parent while they were in the project showed the same strong relationship between accompanying situational stressors and severity of grief that was observed for the sample as a whole, even though the parents' deaths were less sudden overall than other types of bereavement (49). It is hoped that with continued research attention to the development of effective bereavement interventions, persons with mental illness can be empowered to control the situational factors that so powerfully shape their lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 MH-060828 from the National Institute of Mental Health, by collaborative agreement SM-51831 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and by endowments from the van Ameringen Foundation, the Rhodebeck Charitable Trust, and Llewellyn & Nicholas Nicholas.

Dr. Macias, Dr. Jones, Dr. Barreira, and Mr. Rodican are affiliated with the department of community intervention research at McLean Hospital, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, Massachusetts 02478-9106 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Harvey is with the department of psychology at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. Dr. Harding is with the center for the study of human resilience at Boston University.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of and service use among 33 persons with severe mental illness who reported the death of a close friend or family member, grouped by severity of the grief reactiona

a Age (t=2.62, p=.014), gender (χ2=2.35, p=.13), all other group differences p>.20

|

Table 2. Situational factors related to grief intensity and duration among 33 persons with severe mental illness who reported the death of a loved onea

a All group differences statistically significant at p<.05

|

Table 3. is worse for someone who must alsoRegression analysis of predictors of the severity of grief among 33 persons with severe mental illness who reported the death of a loved onea

a Full Model: F=4.88, df=9, 32, p=.001; adjusted R2=.521

1. Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, et al: Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:616–623, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. Prigerson HG, Bridge J, Maciejewski PK, et al: Influence of traumatic grief on suicidal ideation among young adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1994–1995, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Cox G, Bendiksen R, Stevenson R: Complicated Grieving and Bereavement: Understanding and Treating People Experiencing Loss. Amityville, NY, Baywood, 2002Google Scholar

4. Day R: Schizophrenia, in Life Events and Illness. Edited by Brown GW, Harris TO. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

5. Finley-Jones RA, Brown GW: Types of stressful life event and the onset of anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychological Medicine 11:803–815, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Avison WR, Turner RJ: Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: disaggregating the effects of acute and chronic strains. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29:253–264, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Swenson JR, Dimsdale JE: Hidden grief reactions on a psychiatric consultation service. Psychosomatics 30:300–306, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Clayton PJ: Bereavement and depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:34–40, 1990Google Scholar

9. Piper W, Ogrodniczuk J, Azim H, et al: Prevalence of loss and complicated grief among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Services 52:1069–1074, 2001Link, Google Scholar

10. Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ: Surviving adversity: event decay, vulnerability, and the onset of anxiety and depressive disorder. European Archive of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 249:86–95, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mazure C, Bruce M, Maciejewski P, et al: Adverse life events and cognitive-personality characteristics in the prediction of major depression and antidepressant response. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:896–903, 2000Link, Google Scholar

12. Bonanno G, Notarius C, Gunzerath L, et al: Interpersonal ambivalence, perceived relationship adjustment, and conjugal loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:1012–1022, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Horowitz M, Milbrath C, Bonanno G, et al: Predictors of complicated grief. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss 3:257–269, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Ginzburg K, Geron Y, Solomon Z: Patterns of complicated grief among bereaved parents. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 45:119–132, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Meyer B: Coping with severe mental illness: relations of the Brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 23:265–277, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Rando TA: Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Champaign, Ill, Research Press, 1993Google Scholar

17. Worden JW: Tasks and mediators of mourning: a guideline for the mental health practitioner. In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice 2:73–80, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Worden JW: Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Guide for the Mental Health Practitioner. New York, NY, 2001Google Scholar

19. Parkes CM: Risk factors in bereavement: implications for the prevention and treatment of pathologic grief. Psychiatric Annals 20:308–313, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Ross EB: Life After Suicide: A Ray of Hope for Those Left Behind. New York, Insight Press, 1997Google Scholar

21. Amiel-Lebigre F, Chevalier A: Differential metabolization of the impact of life events on subjects hospitalized for depressive and anxiety disorders: case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37:74–79, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Bauer J, Bonanno G: I can, I do, I am: the narrative differentiation of self-efficacy and other self-evaluations while adapting to bereavement. Journal of Research in Personality 35:424–448, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG: Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:447–457, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Carr D, House J, Wortman C, et al: Psychological adjustment to sudden and anticipated spousal loss among older widowed persons. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 56B:S237-S248, 2001Google Scholar

25. Pennebaker JW: Opening Up. New York, Morrow, 1990Google Scholar

26. Spooren D, Henderich H, Jannes C: Survey description of stress of parents bereaved from a child killed in a traffic accident: a retrospective study of a victim support group. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 42:171–185, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Large T: Some aspects of loneliness in families. Family Process 28:25, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Richardson V, Balaswamy S: Coping with bereavement among elderly widowers. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 43:129–144, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Rosenblatt P, Karis T: Economics and family bereavement following a fatal farm accident. Journal of Rural Community Psychology 12:37–51, 1993Google Scholar

30. Demmer C: Grief and survival in the era of HIV treatment advances. Illness, Crisis, and Loss 8:5–16, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Lyons RF, Sullivan MJL: Curbing loss in illness and disability: a relationship perspective, in Perspectives on Loss: A Sourcebook. Edited by Harvey JH. Philadelphia, Brunner/Mazel, 1998Google Scholar

32. Morse G: On being homeless and mentally ill: a multitude of losses and the possibility of recovery, in Loss and Trauma: General and Close Relationship Perspectives. Edited by Harvey JH, Miller ED. Philadelphia, Brunner-Routledge, 2000Google Scholar

33. Harvey JH: Perspectives on Loss and Trauma: Assaults on the Self. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2002Google Scholar

34. Harvey JH, Miller E: Toward a psychology of loss. Psychological Science 9:429–434, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Test MA, Knoedler W, Allness DJ, et al: Comprehensive community care of persons with schizophrenia through the Programme of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT), in Toward a Comprehensive Therapy for Schizophrenia. Edited by Brenner HD, Boker W, Genner R. Seattle, Hogrefe and Huber, 1997Google Scholar

36. Anderson SB: We Are Not Alone: Fountain House and the Development of Clubhouse Culture. New York, Fountain House, Inc, 1998Google Scholar

37. Horowitz M, Siegel B, Holen A, et al: Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:904–910, 1997Link, Google Scholar

38. Prigerson H, Frank E, Kasl S, et al: Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:22–30, 1995Link, Google Scholar

39. Zisook S, Devaul R, Click M: Measuring symptoms of grief and bereavement. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1590–1593, 1982Link, Google Scholar

40. Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, et al: Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: a preliminary empirical test. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:67–73, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Enright BP, Marwit SJ: Diagnosing complicated grief: a closer look. Journal of Clinical Psychology 58:747–757, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Armeli S, Gunther KC, Cohen LH: Stressor appraisals, coping and post-event outcomes: the dimensionality and antecedents of stress-related growth. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 20:366–395, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Larsen DL, Attkisson WA, Hargreaves W, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197–207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Hyman S: Mental health in an aging population: the NIMH perspective. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 9:330–339, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Lefley H, Hatfield A: Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services 50:369–375, 1999Link, Google Scholar

47. Smith GC, Hatfield AB, Miller DC: Planning by older mothers for the future care of offspring with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1162–1166, 2000Link, Google Scholar

48. Wasow M: When I'm gone: mourning the dearly departed…slightly before departure, in Speculative Innovations for Helping People With Serious Mental Illness. Edited by Wasow M. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1999Google Scholar

49. Jones D, Harvey J, Giza D, et al: Parental death in the lives of people with serious mental illness. Journal of Loss and Trauma 8:307–322, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar