A Ten-Year Follow-Up of a Supported Employment Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Supported employment has steadily increased in prominence as an evidence-based mental health practice, and research shows that the service significantly improves employment outcomes over one to two years. The objective of this study was to examine the outcomes of supported employment ten years after an initial demonstration project. METHODS: The study group consisted of 36 clients who had participated in a supported employment program at one of two mental health centers in 1990 or 1992. Clients were interviewed ten years after program completion about their employment history, facilitators to their employment, and their perceptions of how working affected areas of their lives. RESULTS: Seventy-five percent of the participants worked beyond the initial study period, with 33 percent who worked at least five years during the ten-year period. Current and recent jobs tended to be competitive and long term; the average job tenure was 32 months. However, few clients made the transition to full-time employment with health benefits. Clients reported that employment led to substantial benefits in diverse areas, such as improvements in self-esteem, hope, relationships, and control of substance abuse. CONCLUSIONS: On the basis of this small sample, supported employment seems to be more effective over the long term, with benefits lasting beyond the first one to two years.

Supported employment has steadily spawned greater interest within the mental health, rehabilitation, and advocacy communities and is considered to be an evidence-based mental health practice (1). Under the rubric of recovery, consumers have emphasized the importance of functional outcomes and quality of life (2). The ideological commitment to community integration focuses on adult roles in the community rather than dependent roles in segregated settings (3). The President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (4), the Surgeon General (5), the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (6), and the National Institute of Mental Health (7) have identified the importance of employment as an outcome of mental health rehabilitation.

By definition, supported employment assists people with the most severe disabilities so that they are able to obtain competitive employment directly—on the basis of the client's preferences, skills, and experiences—and provides the level of professional help that the client needs. Competitive employment includes jobs that have permanent status, pay at least minimum wage, and are not set aside for people with disabilities, that is, anyone can apply. Research has consistently shown that supported employment is more successful than previous approaches in helping persons with severe mental illnesses to attain competitive jobs (1,8,9,10,11). For example, according to the Cochrane Review, rates of competitive employment were three times as high in supported employment programs as in other programs (11,12). This systematic review found that clients who received supported employment were significantly more likely to be in competitive employment than those who received prevocational training; for example, at 12 months 34 percent of clients in supported employment programs were employed, compared with 12 percent of clients in prevocational training programs.

In addition to higher rates of competitive employment, clients in supported employment programs report high satisfaction with their jobs and their improved financial status (12). However, one limitation of existing follow-up studies is that nearly all the studies span one to two years, a relatively brief period (13). Other limitations of these follow-up studies are that many of the jobs obtained in supported employment last less than six months, and clients receive little subsequent follow-up after the study is completed (14).

A few supported employment studies that were followed up have examined the persistence of employment outcomes. McHugo and colleagues (15) followed a group of clients who participated in a supported employment study for two years beyond the original study, which lasted for 18 months. Despite the erosion of vocational services because of the loss of grant funds, the high rate of competitive employment in this group was maintained for two additional years. There was also some evidence that continued supports were related to continued success in employment. In another long-term study, Bond and colleagues (16) also found persistence of employment in a setting in which vocational supports continued three years after a supported employment grant was terminated. However, other studies found that employment rates decreased rapidly after grant funds were terminated (17,18).

We conducted a ten-year follow-up of former day treatment clients who were originally studied when two separate day treatment programs were converted to supported employment programs in the early 1990s. Our hypotheses were that clients who had participated in the original supported employment program would obtain jobs over the ten-year period that would be characterized by longer job tenure and high satisfaction. Given the limitations imposed by rules for benefits and federal health insurance, we also hypothesized that the majority of participants would remain on Social Security benefits and Medicaid insurance over the ten-year period.

Methods

Setting

Two rural rehabilitative day treatment centers in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and Claremont, New Hampshire, closed in 1990 and 1992, respectively. These centers then substituted supported employment programs based on the Individual Placement and Support model. This model emphasizes the integration of vocational and clinical services; rapid job search; matching jobs to clients' preferences, skills, and experiences; and ongoing job supports (19). Both program conversions demonstrated increases in competitive employment outcomes without adverse effects (20,21,22). Importantly, both centers have maintained their focus on supported employment since the program conversion. Services are organized into multidisciplinary teams in which employment is supported by all team members. In the original study of the centers' supported employment programs, clients were followed for one year to determine how they were affected by program conversion and by the supported employment program (20). Clients of the original study, as well as new clients, share the mental health centers' view of the importance of work and community integration. Since the day treatment programs closed in the early 1990s, the agencies have shown no interest in reopening the program. However, an expansion of social opportunities for clients has occurred through the development of consumer-run recovery centers (23).

Participants

For our ten-year follow-up study, we attempted to locate all participants who had been defined as regular users of day treatment services in 1990 or 1992. These clients were the primary focus of the original one-year follow-up study (20,24). We followed a standardized informed consent procedure, explaining the study and reading the consent statement to the participant. These procedures as well as the interview described below were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of both Dartmouth College and the state of New Hampshire.

Measures

We developed a semistructured interview specifically for this study. (The interview is available from the second author.) The interview gathered information about demographic characteristics, including Social Security benefits, clients' work history for the ten-year period, facilitators of employment, and clients' perceived effects of working. To measure facilitators, we asked participants several open-ended questions about problems they had encountered when they tried to find or keep a job and things that helped them to find or keep a job. These open-ended questions were followed by rating scales that asked participants to rate the helpfulness of 20 different potential facilitators (1, not at all; 2, some; 3, a lot). Facilitators included having someone to encourage them to work and having someone to help them practice for a job interview. Perceived effects of working were assessed with two open-ended questions that asked the participant to identify the positive and negative aspects of working. We followed these questions with structured ratings of how work affected the frequency of services and the supports clients received. Specifically, participants were asked whether working affected how often they saw their case manager, psychiatrist, and family members; how often they went to the hospital; or how much medication they needed (1, less; 2, the same; 3, more). Finally, we asked participants to rate how working affected other areas of their lives, such as symptoms, medication side effects, and self-confidence (1, worse; 2, the same; or 3, better). Interviews were conducted by the authors in 1999 and 2000.

Results

Study group characteristics

Of the 62 clients who were regular day treatment users originally included in the one-year follow-up study, we were able to locate and interview 36 clients, or 58 percent. Seven clients had moved and could not be located, 12 declined to be interviewed, three were hospitalized or unable to give informed consent, and four were deceased. Participants in the ten-year follow-up study group were significantly younger than nonparticipants at the time of the original study; participants had a mean±SD age of 36.5±10 and nonparticipants had a mean age of 43.4±13.2 (t=2.32, df=60, p<.05). Participants of the ten-year follow-up study did not differ significantly from nonparticipants in other available baseline characteristics for which data were available, such as gender, educational level, or diagnosis. In addition, at the time of the original study, participants of the ten-year follow-up study did not differ from nonparticipants in employment outcomes in the categories of presence of community employment, hours worked, and wages earned. Of the 36 participants, 31 (86 percent) were still receiving services from the agency.

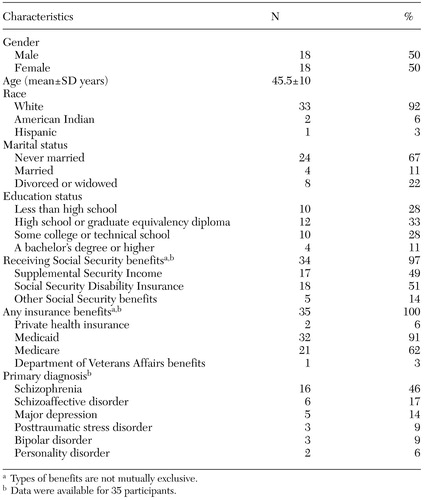

Demographic characteristics of the follow-up study group are shown in Table 1. Of note is the finding that 97 percent of the participants were receiving some form of Social Security benefits at the time of the interview. Similarly, 91 percent were receiving public health insurance through Medicaid.

Employment history

At the time of our study, the vast majority of clients (33 clients, or 92 percent) reported having participated in work activity during the past ten years, including paid work, volunteer positions, sheltered work, and homemaking; 17 clients (47 percent) were currently employed at the time of the interview. We examined patterns of work over time based on the type, frequency, and duration of work reported. Five clients (14 percent) did not work for pay at all during the ten-year period, and an additional four clients (11 percent) worked in the initial years after program conversion. About a third of the study group (11 clients, or 31 percent) worked sporadically throughout the entire ten-year period; four (11 percent) were sporadic in their work initially, but by the time of the ten-year follow-up study, they had become workers with at least 12 months of continuous employment. Finally, 12 clients (33 percent) were consistently employed for at least five years of the ten-year follow-up period. For those who worked, the mean number of jobs held during the past ten years was 3.1±1.9, ranging from one to seven.

We compared workers who were consistently employed for at least five years of the ten-year follow-up period (N=16) with the others (N=20) on the background characteristics listed in Table 1. Workers who were consistently employed were more likely than the remainder to be male (69 percent compared with 35 percent; χ2=4.05, df=1, p<.05) and were less likely to be insured through Medicaid (81 percent compared with 100 percent; χ2=3.99, df=1, p<.05). The two groups did not differ significantly on the remaining variables.

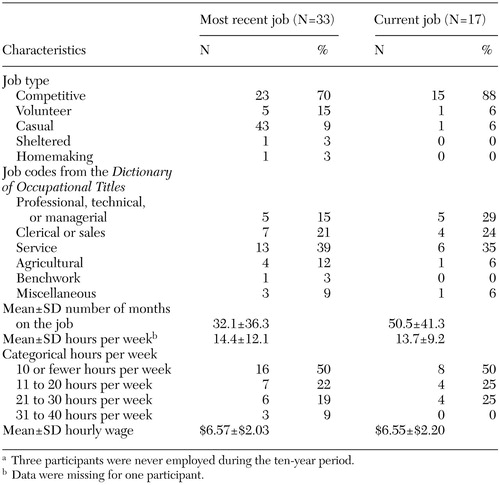

Job descriptors for persons who were employed over the ten-year period are shown in Table 2. Data are given for persons with a recent job (N=33) and for persons with a current job (N=17). Of the clients who detailed their most recent job, 13 clients held a competitive job in the service industry, for example, a clerk at donut shop or a maintenance person (39 percent); five clients (15 percent) were employed competitively in a professional, technical, or managerial position, for example, a crisis respite worker or a peer counselor. The crisis respite and peer counselor positions were classified as competitive even though the positions were designed for consumers, because the designation was based on their experiences and skills rather than on their mental disability. The mean length of time, number of hours worked per week, and rate of pay for the most recent and the current position are shown in Table 2.

We examined rates of employment in the original one-year follow-up study to see whether clients who were currently employed in our ten-year follow-up study were the same clients who were the most successful in the original study. Of the 17 participants who were currently employed, nine (53 percent) had also worked during the first year of the study, and of the 19 participants who were not currently employed, six (32 percent) had worked during the original one-year follow-up study, although the results were not significant. The two employment groups did not differ significantly in hours worked or wages earned during the original study. Clients who were currently employed at the time of our study had worked a mean of 126.3±249 hours during the original study period, compared with 117.4±300.3 hours for clients who were not currently employed. Clients who were currently employed at the time of our study had earned a mean of $543.06± $1,150.43 during the entire period of the original study, compared with $738.37±$1,880.49 during the original study for clients who were not currently employed.

Facilitators of work

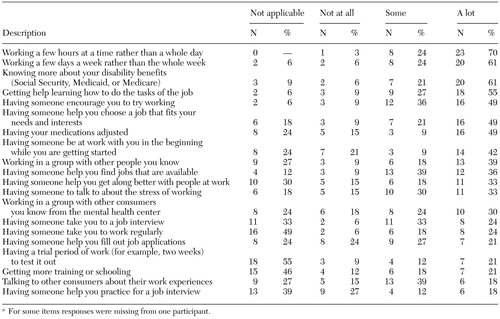

As shown in Table 3, clients with work experience reported that several factors were very helpful. For example, working reduced schedules in terms of hours per day or number of days per week and knowing about disability benefits were the facilitators cited most frequently by clients.

Perceived effects of work

In terms of the support received, most participants reported that work generally did not have much effect on how often they were in contact with professional and nonprofessional supporters. Most clients responded "same" when asked whether work affected how often they saw their case manager (19 clients, or 63 percent), psychiatrist (20 clients, or 63 percent), and family members (23 clients, or 70 percent); how often they went to the hospital (13 clients, or 42 percent); and the amount of medication they needed (20 clients, or 63 percent). A substantial minority of participants reported that they saw their psychiatrist less (ten clients, or 31 percent) and went to the hospital less (12 clients, or 39 percent) because of working. (Ns vary because of missing data.)

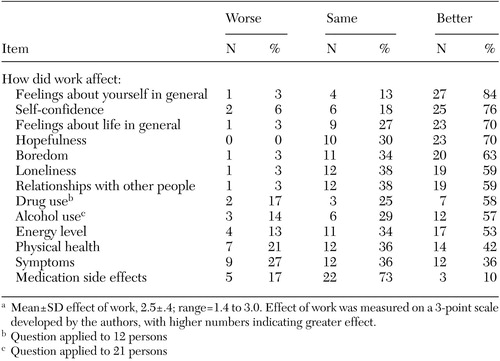

Table 4 displays the impact of work on different aspects of the participants' lives. Notably, most participants reported that their symptoms and the side effects of their medications were the same whether they worked or not. On the remaining items, the majority of clients reported that work made these aspects better. The particular areas of improvement ranged from physical health (14 clients, or 42 percent) to "feelings about yourself in general" (27 out of 32 clients, or 84 percent).

Discussion

Overall, the consumers in our study group demonstrated substantial employment rates during the ten years that followed the conversion from a day treatment program to a supported employment program. Almost all the consumers reported that they were employed at some point during the ten-year follow-up period, and 17 consumers (47 percent) were employed at the time of the ten-year follow-up interview. The majority of the jobs were competitive, with consumers making at least minimum wage in a community setting. These rates of employment are very high given the nature of the study group—high users of day treatment in the original conversion study. In the original study, which followed clients for one year, only 29 percent of day treatment participants were employed (24), and a recent survey of other day treatment participants found that only 16 percent were employed (25). Thus the employment rates in our study group are strong.

Of the participants who did work over the ten-year period, many of the jobs they held were long term, with an average tenure of almost three years. In addition, participants noted many positive effects that working had on their lives, particularly in reference to their perceptions of self-worth. Thus supported employment seems to be more effective for the long term, with benefits that last beyond the first one to two years, the duration of most follow-up studies. Notably, 86 percent of participants in this study continued their involvement with a mental health center that included a focus on supported employment, a focus that continued throughout the ten-year follow-up period. These mental health centers provide a culture in which work is valued and consumers are expected to work. Thus the participants in our study likely had continued contact with supported employment services in the intervening years.

Interestingly, participants' success in the original one-year follow-up study appeared to have minimal impact on their later employment. Clients who were employed at the ten-year follow-up were not more likely than those who were not employed to have been employed, to have made more money, or to have worked more hours during the original study. Although the lack of statistical differences may result in part from the small sample size, of the 17 study participants currently employed, eight (47 percent) had not worked at all during the first year of the program. Some clients initially may not be interested in competitive work, but they still can become consistently employed. Thus some clients may need more than a year of supported employment before positive effects are seen. This result highlights the need for a long-term perspective when working with clients in supported employment programs. The result also points to the need for longer follow-up periods in studies of supported employment.

Although the majority of participants were consistently employed by the end of the ten-year period, supported employment may not be appropriate for everyone: five participants (14 percent) did not work for pay at all over the course of our study, and an additional 11 percent worked a little early on, but not for very long. Because the original study examined all regular users of day treatment, not just those with stated vocational goals, all the participants may not have wanted to work. Supported employment is designed for consumers who want to work. Other clients may have tried working and then decided to pursue other goals. Thus we expect that some clients would not seek or try to maintain employment over the ten-year period.

Despite positive employment results, almost all the consumers continued to receive Social Security benefits, which is not surprising given the real and perceived barriers to giving up of benefits (26,27). In our study, half of those who were employed worked ten hours a week or less. The average hourly wage was less than $7, and the maximum reported wage did not exceed $10. It would be nearly impossible to sustain independent living, for which many clients would require expensive medications, at this level of employment. On the other hand, it may be that some consumers choose to work at this low level so that they can keep their government benefits. Benefits counseling often includes discussions about the maximum pay a consumer can receive and still maintain current benefits (28). Policy changes, such as the Ticket to Work and Work Incentive Improvement Act, may remove some of these barriers by increasing the ability of consumers to make choices and reducing their concerns about benefit loss (29).

Consistent with the idea of community integration as a key factor in recovery, most of the consumers reported that working improved multiple areas of their lives, particularly feelings about themselves and life in general. Working made the participants feel less bored and lonely and more self-confident and hopeful about the future. These findings are even more interesting in light of the finding that most participants did not think that working improved their symptoms or medication side effects. Rehabilitation specialists have argued for years that rehabilitation can be successful for persons with mental illness, regardless of their symptoms (30).

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, the study group was small, and we conducted follow-up interviews with 58 percent of the original sample, or 62 percent of the living participants. Given the severity of illness of the participants in the original study and the ten-year follow-up period of our study, this participation rate is good. However, the combination of the small sample and the rural setting of the supported employment program leads to concern about the generalizability of our findings. We need further data from larger, more diverse samples. In addition, the interviews were based on self-report and were not validated by agency records or other informants. Finally, we had no method for controlling factors that may have contributed to outcomes, and as noted above, the large majority of participants were involved in a mental health program that emphasized supported employment consistently over many years. Thus it is impossible to make clear causal attributions for our study outcomes, for example, to determine the effects of initial intervention versus the effects of ongoing treatment. The most parsimonious interpretation of the data is that ongoing involvement in the mental health program, including supported employment, over ten years was likely related to the pattern of improved vocational outcome. Although this was not a controlled study, other interpretations, such as delayed effects, are plausible but unlikely and untestable.

Despite these limitations, our study represents a new perspective on the effectiveness of supported employment. Our study is the first look at the long-term impact of supported employment, with follow-up data ten years after the initial conversion from a day treatment program to a supported employment program. Our findings are encouraging in terms of rates of employment, particularly competitive employment, and the benefits of working that clients perceived in other areas of their lives. Our findings also raise questions about whether self-sufficiency is a realistic goal for most mental health consumers. Given the current constraints of insurance and benefits, most consumers appear to focus on goals, such as increasing income, self-worth, and community integration, rather than on self-sufficiency.

Dr. Salyers is affiliated with the ACT Center of Indiana and the department of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University, LD124, 402 North Blackford, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Becker is with the department of community and family medicine and Dr. Drake and Dr. Torrey are with the department of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School in Lebanon, New Hampshire. Mr. Wyzik is with West Central Behavioral Health and Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics at the time of the ten-year follow-up interview for 36 adults who participated in a supported employment program in 1990 or 1992

|

Table 2. Characteristics of jobs held by 33 adults during the ten years after they participated in a supported employment programa

a Three participants were never employed during the ten-year period.

|

Table 3. Facilitators of employment cited by adults who had participated in a supported employment program and who were employed during the ten-year follow-up period (N=33)a

a For some items responses were missing from one participant.

|

Table 4. Impact of employment on adults who had participated in a supported employment program and who were employed during the ten-year follow-up period (N=33)a

a Mean±SD effect of work, 2.5±.4; range=1.4 to 3.0. Effect of work was measured on a 3-point scale developed by the authors, with higher numbers indicating greater effect.

1. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Ralph RO, Lambert D: Needs Assessment Survey of a Sample of AMHI Consent Decree Class Members. Portland, Maine, University of Southern Maine, Edmund S Muskie Institute of Public Affairs, 1996Google Scholar

3. Carling PJ: Return to Community; Building Support Systems for People With Psychiatric Disabilities. New York, Guilford Press, 1995Google Scholar

4. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. Rockville, Md, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

5. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

6. NAMI Strategic Plan, 2001–2003. Alexandria, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2001Google Scholar

7. Bridging Science and Service: A Report by the National Advisory Mental Health Council's Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

8. Cook J, Razzano L: Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:87–103, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Crowther R, Marshall M, Bond GR, et al: Vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental disorders [Cochrane Review], in Cochrane Library (issue 1). Oxford, England, Update Software, 2000Google Scholar

10. Crowther RE, Marshall M, Bond GR, et al: Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review. British Medical Journal 322:204–208, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF: Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): Schizophrenia PORT Update. Expert Panel Review. Baltimore, Md, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Mental Health Services Research, 2002Google Scholar

12. Latimer EA: Economic impacts of supported employment for the severely mentally ill. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46:496–505, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Drake RE, Becker DR, Clark RE, et al: Research on the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:289–301, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR, et al: Job terminations among persons with severe mental illness participating in supported employment. Community Mental Health Journal 34:71–82, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Becker DR: The durability of supported employment effects. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:55–61, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Bond GR, Dietzen LL, McGrew JH, et al: Accelerating entry into supported employment for persons with severe psychiatric disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology 40:91–111, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Danley KS, Rogers ES, MacDonald-Wilson K, et al: Supported employment for adults with psychiatric disability: results of an innovative demonstration project. Rehabilitation Psychology 39:269–276, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

18. McFarlane WR, Stastny P, Deakins, SA, et al: Employment outcomes in family-aided assertive community treatment (FACT). Presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, Boston, Mass, Oct 6–10, 1995Google Scholar

19. Becker DR, Drake RE: Individual Placement and Support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Mental Health Journal 30:193–206, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al: Rehabilitation day treatment vs supported employment: I. vocational outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal 30:519–532, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: vocational outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Torrey WC, Becker DR, Drake RE: Rehabilitative day treatment versus supported employment: II. consumer, family, and staff reactions to a program change. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:67–75, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Torrey WC, Mead S, Ross G: Addressing the social needs of mental health consumers when day treatment programs convert to supported employment: can consumer-run services play a role? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:73–75, 1998Google Scholar

24. Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al: Day treatment versus supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: a replication study. Psychiatric Services 47:1125–1127, 1996Link, Google Scholar

25. McQuilken M, Zahniser JH, Novak J, et al: The Work Project Survey: consumer perspectives on work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 18:59–68, 2003Google Scholar

26. MacDonald-Wilson KL, Rogers ES, Ellison ML, et al: A study of the Social Security Work Incentives and their relation to perceived barriers to work among persons with psychiatric disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 48:301–309, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Johnson-Lamarche H, Baird P: The barriers to employment faced by persons with disabilities: problems and solutions, in Report to the Governor and the 1997 Vermont General Assembly, January 1997. Waterbury, Vt, Vermont Department of Aging and Disabilities, 1997Google Scholar

28. Tremblay T, Smith J, χie H, et al: The impact of specialized benefits counseling services on Social Security Administration disability beneficiaries with psychiatric disabilities in Vermont. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, in pressGoogle Scholar

29. Golden TP, O'Mara S, Ferrell C, et al: A theoretical construct for benefits planning and assistance in the Ticket to Work and Work Incentive Improvement Act. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 14:147–152, 2000Google Scholar

30. Anthony WA, Cohen M, Farkas MD, et al: Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 2002Google Scholar