Depression and the Ability to Work

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Depression can have a serious impact on a person's ability to work. The purpose of this study was to describe depressed persons who work and depressed persons who do not work and to identify factors related to depressed persons' working. METHODS: The combined 1994 and 1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplement was used to identify persons aged 18 to 69 with depression. Sociodemographic, health, functional, and disability characteristics of working depressed persons and nonworking depressed persons were compared with use of a chi square test of significance. After adjustment for sociodemographic variables, multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with work among depressed persons. RESULTS: Approximately half of the persons who reported major depression were in the labor force. Compared with nonworking depressed persons, working depressed persons tended to be younger, to be male, to be better educated, to have a higher income, to live alone or with a nonrelative, and to live in an urban or suburban location. They less often perceived themselves as unable to work or as disabled and were healthier and less impaired by social, cognitive, and physical limitations than their nonworking counterparts. After sociodemographic factors were controlled for, health and functional characteristics were strongly associated with depressed persons' working. CONCLUSIONS: Depressed persons who work and who do not work differed across sociodemographic, health, functional, and disability factors. Understanding the factors associated with depressed persons' working and not working may help policy makers, employers, and clinicians shape health care benefits packages, employee assistance programs, disability programs, and treatment programs appropriately. In particular, it may be important to focus on individuals with depression and comorbid general health conditions.

Depression can have a serious impact on cognitive, social, and physical functioning (1). The United States loses between $30 billion and $44 billion in direct medical, mortality, and productivity costs each year as a result of depression (2,3,4). Moreover, studies show that depression is related to work impairment (5), disability and lost work days (6,7,8,9), and reduced productivity on the job (10).

Many effective treatments and management protocols are available to ease the symptoms of depression (11,12,13,14), although only about 20 percent of persons with major depression are adequately treated (15). Depression treatment has also been shown to be cost-effective (16), to keep depressed persons employed (17,18), and to improve the productivity of depressed persons who are already working (19). Moreover, it has been hypothesized that the amount of money saved by treating depressed workers could result in savings to employers that would more than make up for the costs of treatment (20,21,22,23).

Given that between 5 and 25 percent of Americans will experience depression during their lifetime (15,24) and that depression is likely to have a major effect on the ability to work among those who are depressed, it appears to be advantageous for society, as well as good business practice, to assist individuals with depression in remaining at or returning to work. However, little is known about the characteristics of depressed persons who do work and who do not work and about the factors that are associated with depressed persons' working.

Consequently, in this cross-sectional study we used a large nationally representative sample of depressed persons to examine the sociodemographic, health, functional, and disability characteristics of persons who work and those who do not work. The purpose of the study was to compare working depressed persons and nonworking depressed persons and to identify the factors that are associated with depressed persons' working.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the 1994 and 1995 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplement (NHIS-D) to identify persons with depression. The NHIS is an annual survey sponsored by the National Center for Health Statistics (25). The NHIS-D was a special supplement to the NHIS core. The supplement was administered during 1994 and 1995 and collected detailed information on functional limitations, limitations in daily activities, disability, and mental health.

NHIS data were obtained by in-person interviews of household members. Interviews were conducted with a probability sample of households by using a stratified multistage probability design (25). A total of 107,469 persons were in the 1994 sample, and 95,091 persons were in the 1995 sample.

Population

All working-age persons, aged 18 to 69, were included in the study. Persons were considered to have depression if they responded "yes" to the question "During the past 12 months, did [you or the household member] have major depression? Major depression is defined as 'depressed mood and loss of interest in almost all activities for at least two weeks.'"

Variables

Working was defined as participation in the labor force. Participants in the labor force included those who were currently employed and had worked in the past two weeks; those who had a job but had not worked in the past two weeks, for example, were not on layoff or looking for a job; and those who were looking for a job or who had been laid off.

Disability was examined in two ways. We used the NHIS-D variable on ability to work to examine four possibilities: unable to work, limited in the amount or kind of work a person could perform, limited in other activities, and not limited. We also defined disabled by using a two-part algorithm: answering "yes" to the question "Does any impairment or health problem keep [you or the household member] from working at a job or business?" and reporting not working in the past two weeks. In other words, disability was an impairment or health problem affecting the ability to work and not working in the past two weeks.

Self-reported health status was operationalized with the question "Would you say [your or the household member's] health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?" A person was considered to have an attributable health condition if a condition was reported as the main or secondary cause of inability to work or of limitation in working. Additionally, an attributable health condition was defined when it was reported as the cause of a problem with an activity of daily living—for example, bathing, dressing, or eating—or an instrumental activity of daily living—for example, preparing meals, managing money, or grocery shopping—or as the cause of a functional limitation—for example, a social, cognitive, or physical limitation. The number of attributable health conditions reported for each person was then summed.

A person with social limitations was described as having trouble making or keeping friends, a lot of trouble getting along in social settings, or serious trouble coping with day-to-day stresses (26). A person was deemed to have cognitive limitations when that person was described as having a lot of trouble concentrating for long enough to complete tasks or as being frequently confused, disoriented, or forgetful (26). To be included as a cognitive or social limitation, the problem had to interfere seriously with the person's life. A person with a physical limitation was described as having one or more problems with activities of daily living or as having one or more physical functional limitations—for example, lifting something as heavy as ten pounds, walking about a quarter of a mile, or holding a pen—or as being in fair or poor health (26).

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, race, residential description, that is, urban and suburban areas versus rural areas; living arrangement; and education level. For the purpose of our study, urban and suburban areas were grouped together, because access to and type of treatment for these areas are likely different than for rural areas. It was hypothesized that job flexibility would be an important factor in the association between working and not working for depressed persons (27). Such flexibility might provide a depressed person with the ability to work reduced hours, rearrange work schedules and work procedures, and take time off during depressive episodes. We used education level as a proxy for job flexibility. In addition, for persons who were in the labor force, we categorized the reported job into categories that appeared to be related to job flexibility: white collar, for example, executive, administrative, and managerial occupations; blue collar, for example, farming, forestry, fishing, transportation, handlers, and laborers; and a middle category that could not be categorized as either white or blue collar, for example, sales, protective services, and other service jobs. White collar jobs were considered to be more flexible than blue collar jobs.

Statistical analysis

We calculated population estimates of employment and disability status among depressed persons. We then compared working depressed persons with nonworking depressed persons by sociodemographic, disability, health, and functional characteristics by using a chi square statistic.

Finally, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis by using labor force participation as the dependent variable. Independent variables consisted of sociodemographic characteristics in one model. We then produced separate models for each health and functional characteristic while adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals are presented.

In order to provide nationally representative estimates and to account for the complex survey design, all analyses used the SUDAAN statistical package, release 7.5, with appropriate weighting.

Results

Comparison of depressed and nondepressed workers

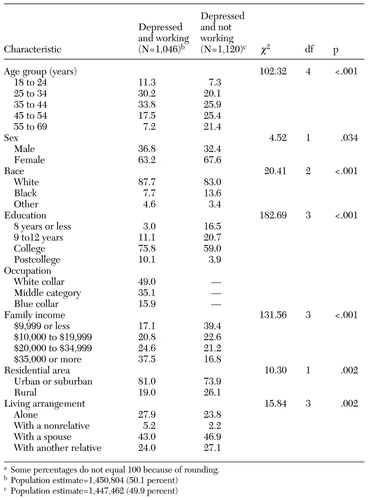

An estimated 2.9 million persons in the United States, or 1.7 percent of the population aged 18 to 69, reported having major depression as defined in the NHIS. Compared with depressed persons who were not working, depressed persons who worked differed significantly in every sociodemographic category examined (Table 1).

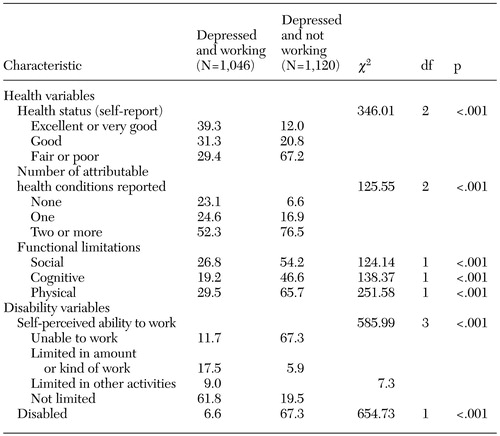

Compared with nonworking depressed persons, working depressed persons were significantly more likely to perceive themselves as healthier, reported fewer attributable health conditions, and were less impaired by social, cognitive, and physical limitations. The perceived ability to work and self-reported disability were also significantly different between depressed persons who worked and who did not work (Table 2).

Factors associated with depressed persons' working

Sociodemographic characteristics were highly associated with depressed persons' working. For example, after the analysis adjusted for all other sociodemographic variables, depressed persons aged 18 to 24 were more likely to work than depressed persons aged 55 to 69 (OR=4.59, CI= 2.69-7.83). Among depressed persons, men were more likely to work than women (OR=1.22, CI=1.02- 1.48) and white persons were more likely to work than black persons (OR=1.89, CI=1.35-2.64). Education level and living alone or with a nonrelative were also significantly related to the work status of depressed persons. For example, persons with five or more years of a postcollege education were more than 11 times as likely to be working than those with fewer than eight years of education (OR=11.14, CI=6.07-20.44). On the other hand, compared with living with a spouse, the odds of working were greater among those living with a nonrelative (OR=1.98, CI=1.02-3.84) or living alone (OR=1.42, CI=1.14-1.78).

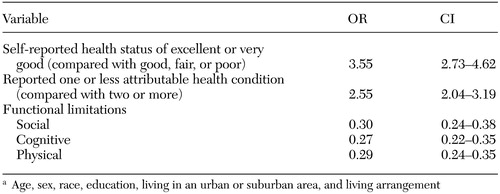

After the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, a relationship was seen between each health and functional characteristic and labor force participation among depressed persons (Table 3). The odds of depressed persons' working were greater among persons who reported excellent or very good health than among those who reported good, fair, or poor health. The odds of being in the labor force were greater for those who reported one or no attributable health conditions for social, cognitive, or physical limitations than for those who reported two or more attributable health conditions.

Discussion

Currently, considerable evidence exists to demonstrate the serious impact that depression can have on the ability to work, absenteeism, and workplace productivity, as well as the usefulness of depression treatment to reduce depressive symptoms and improve function and employment. An understanding of the characteristics of persons with depression who are unable to work or who continue to work at reduced productivity may assist in the development of programs to improve access to health care and adherence to depression treatment.

Our study found that approximately half of the estimated 2.9 million people who considered themselves to have major depression participated in the labor force and showed that depressed persons who work and who do not work are considerably different. Compared with depressed persons who do not work, depressed persons who work are significantly more likely to be younger, to be male, and to be better educated, to have a higher income, to live alone or with a nonrelative, and to live in an urban or suburban location. A large percentage of depressed persons who are employed work in white collar jobs and are less likely to perceive themselves as unable to work or to be disabled. Finally, depressed persons who work are healthier than their nonworking counterparts. Working depressed persons perceive themselves to have a better overall health status, report fewer health conditions that limit their ability to work or to perform activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, and have fewer social, cognitive, and physical limitations than nonworking depressed persons.

In addition to this composite of depressed persons who work, we found that health status and education level were strongly associated with depressed persons' working, even after controlling for other related factors, such as age, gender, race, living arrangement, and residential area. Depressed persons who perceived themselves to be in excellent or very good health were 3.6 times as likely to be in the labor force as those who perceived themselves to be in good, fair, or poor health. Those with one or no attributable health conditions were 2.6 times as likely to work as those with two or more attributable health conditions. Those who reported at least one social, cognitive, or physical limitation were about one-third as likely to be in the labor force as those who did not report these limitations.

This study had some weaknesses. All information obtained in the NHIS-D was based on self-report or from a knowledgeable adult reporting for absent members of the family (25). Depression may have been underreported as a result of stigma or failure to recognize or accept depression in oneself or in a family member.

Identification of depression was based on a single-item question. From this question, it was estimated that 1.7 percent of the population aged 18 to 69 had been depressed in the past 12 months. The National Comorbidity Survey found a 12-month prevalence of major depression of 6.6 percent among persons aged 18 and older when using a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (15). The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study of five communities found a cross-site mean for major depression for the past month among adults aged 18 and older of 1.6 per 100 persons when using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, a highly structured interview designed for use by lay interviewers in epidemiologic studies in which items were consistent with the DSM-III definition of depression (28). Our results were more consistent with those of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, even though our results were based on a less sophisticated method for identifying depression and used a working-age group of adults. However, unlike the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, our study could not make distinctions between level of depression severity, and it was based on reports of depression in the past 12 months.

Although the NHIS-D did not provide specific information on job flexibility, the finding on the relationship between education and work status among depressed persons is consistent with the hypothesis that job flexibility may be associated with work status among depressed persons. Further studies will need to elucidate this issue with more direct questioning on the subject.

Despite the above limitations, this study had a number of strengths. Data from the NHIS-D provided a large sample for studying depressed persons who work and who do not work. In addition, this sample is representative of the U.S. population, with a few exceptions, so that conclusions can be drawn for the general population. Persons excluded from this sample were patients in long-term-care facilities; persons on active duty with the U.S. Armed Forces, although their dependents were included; and U.S. nationals living in foreign countries (25). Excluding patients in long-term-care facilities may exclude the elderly population, which should not have interfered with our study's results, because the cutoff in this study was 69 years of age to examine the working-age population.

The health status and functional variables were consistently related to work status among depressed persons. Although it could be argued that the health status and functional limitation measures may be proxies for severity of depression rather than for independent risk factors, our findings on depression were consistent with findings from studies of other chronic diseases (29,30,31). For example, in an analysis of the same NHIS-D database to determine the factors associated with employment among all persons with disabilities, Zwerling and colleagues (29) found several sociodemographic variables, such as age, race, and education, to be associated with workforce participation, as well as with perceived health status and difficulties with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. In another study, Yelin and Katz (30) used the NHIS data for the period 1970 to 1987 and found that the labor force participation rate was higher among persons with activity limitation and musculoskeletal conditions only when compared with those with musculoskeletal conditions plus other chronic conditions. Finally, in a study of musculoskeletal conditions in a population aged 51 to 61, Yelin (31) found that persons with musculoskeletal conditions and no comorbid conditions were less likely to have a work disability than persons with musculoskeletal conditions plus other comorbid conditions. Moreover, a multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that work disability was related to comorbidity, older age, being female, and having less education and fewer functional limitations (31).

Our study found that at least 1.7 percent of the working-age population was depressed within the past 12 months—an estimated 2.9 million individuals. However, this finding does not include persons whose depression was in remission in the past 12 months or whose depressive episode may have occurred before this 12-month period. Moreover, despite the fact that nearly 50 percent of depressed persons reported that they were in the labor force, nearly 30 percent of depressed persons who worked considered themselves unable to work or limited in the amount or kind of work that they could do. This amounts to a substantial proportion of depressed persons in the labor force who may be in need of improved treatment or better access to treatment.

Conclusions

The populations of depressed persons who work and who do not work are clearly different along important parameters. These populations differ in virtually every sociodemographic characteristic, as well as by health status, functional status, and disability characteristics. Factors strongly associated with depressed persons' working are related to their health and functional status, with education level also playing an important contributory role in the likelihood of a person with depression continuing in the workforce. In particular, it may be important to focus on individuals with depression and comorbid general health conditions.

The results of this study help to underscore the societal burden from depression by confirming the large number of depressed persons in the U.S. population. Health care policy makers need to be aware of the cost-effectiveness of depression treatment and the increased likelihood of employment with improvement in depressive symptoms. Employers need to be aware that although at least half of the working-age population who are depressed will continue to work, depression can have a serious effect on the workplace in terms of absenteeism, short- and long-term disability costs, and lower productivity. Employers may wish to develop programs to identify persons who are depressed and to ensure, through benefits packages and health insurance, that depressed persons will receive effective treatment. A better understanding of the characteristics of depressed persons who work and the factors associated with continuance in the labor force will help to shape health care benefit packages, employee assistance programs, disability programs, and treatment programs. Such interventions will be of benefit to workers and employers alike.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and by grant MH-30915 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Elinson is affiliated with Westat, 1441 West Montgomery Avenue, Westbrook Building, 2nd Floor, Rockville, Maryland 20850 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Houck and Dr. Pincus are with the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Dr. Pincus is also with Rand in Pittsburgh. Dr. Marcus is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of depressed persons aged 18 to 69 years who work and who do not work, in percentagesa

a Some percentages do not equal 100 because of rounding.

|

Table 2. Health and disability characteristics of depressed persons aged 18 to 69 years who work and who do not work, in percentages

|

Table 3. Associations between working and health-related variables for depressed persons, with adjustment for sociodemographic characteristicsa

a Age, sex, race, education, living in an urban or suburban area, and living arrangement

1. Pincus HA, Pettit AR: The societal costs of chronic major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62(suppl 6):5–9, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rice DP, Miller LS: Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the United States. British Journal of Psychiatry 34:4–9, 1998Google Scholar

3. Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al: The economic burden of depression in 1990. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:425–426, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al: Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 289:3135–3144, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, Frank RG: The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological Medicine 27:861–873, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524–2528, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Conti DJ, Burton WN: The economic impact of depression in a workplace. Journal of Occupational Medicine 36:983–988, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al: Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Affairs (Millwood) 18(5):163–171, 1999Google Scholar

9. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Sledge WH: Health and disability costs of depressive illness in a major US corporation. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1274–1278, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Greenberg PE, Mickelson KD, et al: The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 43:218–225, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Whooley MA, Simon GE: Managing depression in medical outpatients. New England Journal of Medicine 343:1942–1950, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Simon GE, Katon W, Rutter C, et al: Impact of improved depression treatment in primary care on daily functioning and disability. Psychological Medicine 28:693–701, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, et al: Best clinical practice: guidelines for managing major depression in primary medical care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 7):19–26, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 289:3145–3151, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, Unutzer J, et al: Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1638–1644, 2001Link, Google Scholar

17. Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:212–220, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Schoenbaum M, Unützer J, McCaffrey D, et al: The effects of primary care depression treatment on patients' clinical status and employment. Health Services Research 37:1145–1158, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Berndt ER, Finkelstein SN, Greenberg PE, et al: Workplace performance effects from chronic depression and its treatment. Journal of Health Economics 17:511–535, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Klerman GL, Weissman MM: The course, morbidity, and costs of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:831–834, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Zhang M, Rost KM, Fortney JC, et al: A community study of depression treatment and employment earnings. Psychiatric Services 50:1209–1213, 1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Simon GE, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al: Depression and work productivity: the comparative costs of treatment versus nontreatment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 43:2–9, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Goetzel RZ, Ozminkowski RJ, Sederer LI, et al: The business case for quality mental health services: why employers should care about the mental health and well-being of their employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44:320–330, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

25. Massey JT, Moore TF, Parsons VL, et al: Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1985–1994. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics 2:1–32, 1989Google Scholar

26. Druss BG, Marcus SC, Rosenheck RA, et al: Understanding disability in mental and general medical conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1485–1491, 2000Link, Google Scholar

27. Secker J, Membrey H. Promoting mental health through employment and developing healthy workplace: the potential of natural supports at work. Health Education Research 18:207–215, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Tischler GL, et al: Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychological Medicine 18:141–153, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Zwerling C, Whitten PS, Sprince NL, et al: Workforce participation by persons with disabilities: the National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplement, 1994 to 1995. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44:358–364, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Yelin EH, Katz PP: Labor force participation among persons with musculoskeletal conditions, 1970–1987. Arthritis and Rheumatism 34:1361–1370, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Yelin EH: Musculoskeletal conditions and employment. Arthritis Care Research 8:311–317, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar