Impact of Multiple-Family Groups for Outpatients With Schizophrenia on Caregivers' Distress and Resources

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of multiple-family group treatment on distress and psychosocial resources among family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. METHODS: A total of 97 consumers with schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and their caregivers were randomly assigned to receive multiple-family group treatment (N=53) or standard psychiatric outpatient care (N=44). Reliable and valid measures were used to assess caregivers' distress, caregivers' resources, and consumers' clinical status. RESULTS: After consumers' clinical status and baseline rates of caregivers' distress and caregivers' resources were controlled for, the caregivers of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment experienced greater reductions in distress but no increases in resources compared with caregivers of consumers who received standard psychiatric care. CONCLUSIONS: Multiple-family group treatment reduced caregivers' distress but did not increase caregivers' resources relative to standard psychiatric care.

Family-member caregivers of persons with schizophrenia have substantial demands placed on their personal, financial, social, and emotional resources. These objective demands, along with caregivers' subjective reactions to them, are often referred to as "burden" (1).

Vitaliano and colleagues (2) proposed a model of psychological functioning among caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease that hypothesized caregivers' burden to be the result of an interaction between caregivers' vulnerability and stressors that is tempered by the presence of psychosocial resources. In the case of family-member caregivers of persons with schizophrenia, stressors include consumers' symptoms; adverse events, such as psychiatric hospitalization; and other factors, including short duration of illness. Although previous research has suffered from a paucity of standardized measures and successful replication, each of the aforementioned variables have been associated with increased burden (3,4,5,6,7). Caregivers' vulnerability, including passive coping styles characterized by avoidance, resignation, and self-blame, have also been associated with increased burden (3,8,9).

Conversely, resources such as social support and active coping styles that foster mastery and self-efficacy have been consistently associated with lower burden and distress (9,10,11,12). Dyck and colleagues (3) demonstrated considerable support for Vitaliano and colleagues' model in a sample of caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. The model provides a conceptual framework for predicting the more general effects of family psychoeducation on caregivers' psychosocial functioning.

Family psychoeducation for the management of schizophrenia has been extensively studied and is currently considered a best practice in the treatment of schizophrenia among adults (13). Multiple-family group treatment, developed by McFarlane (14), integrates elements of psychoeducation and behavioral family therapy in a group format with two clinicians and six to eight families. This approach provides information and problem-solving experiences to family members and consumers that are designed to improve the management of schizophrenia.

Multiple-family group treatment begins with a three-session joining phase with each family and consumer. The clinician's goal in the joining sessions is to develop a solid alliance with the family and the patient, to gain information from both the patient and the family about the history of the illness as well as its impact and the resources for managing it. Next there is a one-day psychoeducational workshop, followed by one year of bimonthly group sessions that focus on relapse prevention. Finally, there is then a year of monthly group sessions that focus on social and vocational rehabilitation (14). Multiple-family group treatment has demonstrated a positive effect on consumers' negative symptoms, use of inpatient and outpatient services, and relapse (15,16,17,18).

Vitaliano and colleagues' (2) model predicts that reductions in stressors associated with multiple-family group treatment—for example, consumers' symptoms—will be accompanied by corresponding reductions in caregivers' burden and distress. Reduction in family burden and distress might also be anticipated, given the increase in caregivers' resources through expanded social support networks and beneficial coping strategies that are expected to be learned through the intervention (14).

However, the literature is inconclusive about the effects of family interventions on caregivers' well-being. For example, Mueser and colleagues (19) found that neither applied family management nor supportive family management, which are both similar to multiple-family group treatment in scope and duration, had any effect on caregivers' burden. On the other hand, Stam and Cuijpers (20) found that a family psychoeducational group for caregivers of persons with schizophrenia reduced objective burden relative to that of persons in a control group, and Chou and associates (21) reported that eight-week support groups reduced both depression and burden among caregivers of persons with schizophrenia compared with persons in a control group. In an earlier report from the study reported here, McDonell and colleagues (11) found that multiple-family group treatment had no significant positive effects on caregivers' burden. It was suggested that the treatment's apparent lack of effect on caregivers' burden may have been due to the long duration of psychiatric illness in their sample (about ten years), difficulties in reliably and validly measuring burden, and the lack of an explicit focus of multiple-family group treatment on caregivers' psychological functioning.

This investigation reexamined the impact of multiple-family group treatment on caregivers' outcomes by focusing more specifically on caregivers' distress in the sample of participants who were involved in the same randomized clinical trial conducted by McDonell and associates (11). Whereas subjective burden describes the adverse psychosocial experiences associated with caregiving, distress can be conceptualized as an expression of global psychological dysfunction, which can be independent of the caregiving role.

Compared with the study by McDonell and associates, the study reported here included a larger sample of caregivers of persons with schizophrenia as well as measures that were more psychometrically sound. This study also investigated the impact of multiple-family group treatment on these caregivers by using the model developed by Vitaliano and colleagues (2). On the basis of the model it was hypothesized that over the two-year course of the intervention, caregivers of persons who received multiple-family group treatment would experience greater reductions in distress and greater increases in psychosocial resources than caregivers of consumers who received standard psychiatric care.

Methods

Participants

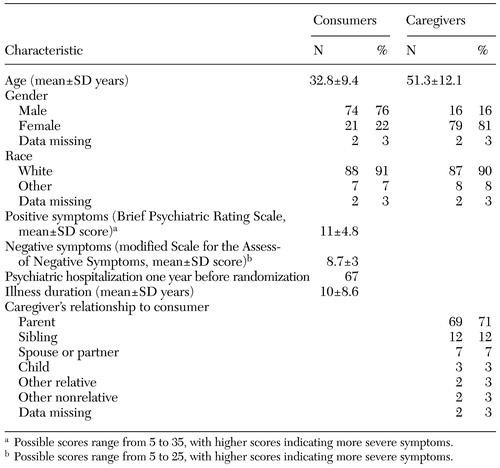

The study received institutional review board approval by all appropriate agencies and institutions, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were 97 consumers who were randomly assigned to receive multiple-family group treatment (N=53) or standard psychiatric care (N=44) and their corresponding family-member caregivers. Descriptive statistics for the sample are listed in Table 1. The caregivers were primarily mothers, and their mean age was 51.3±5.2 years. Consumers had DSM-IV (22) diagnoses of schizophrenia (N=64), schizoaffective disorder (N=32), or other psychotic disorders (N=1) and were living in the community at the time of study entry.

Data were collected for seven cohorts from 1996 to 2001. Twenty-one consumers and their respective caregivers dropped out of treatment over the two-year study period, 12 from multiple-family group treatment and nine from standard psychiatric care; t tests indicated that those who dropped out were not significantly different from those who remained in the study in terms of baseline rates of caregivers' distress, resources, or active coping or in terms of stressors related to consumers' status—that is, positive or negative symptoms or hospitalization status.

Overview of treatment

All consumers enrolled in the study received standard care for persons with schizophrenia at a large community mental health center. Services provided under standard care included case management, clubhouse services, monthly medication management, and crisis services as needed. The consumers in the treatment group also received multiple-family group treatment. Each multiple-family group was composed of six to eight families and two clinicians, who provided the intervention on the basis of the multiple-family group treatment manual of McFarlane and colleagues (23). The originators of the intervention provided initial training in the procedure and monthly supervision of videotaped sessions.

The complete intervention lasted two years for each cohort and included bimonthly meetings during the first year and monthly meetings during the second year. Each session lasted 90 minutes and included socializing about non-illness-related topics, updates on each family's situation, and group problem solving. Sessions during the first year focused on the prevention of relapse and management of the illness and in the second year centered on social and vocational rehabilitation.

Measures

Caregivers' distress. All caregiver variables were assessed at baseline and at 12 and 24 months after randomization, except for perceived stress, which was assessed monthly. Perceived stress was measured with use of the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (24), which asked caregivers to rate the level of stress they felt over the previous month. Baseline, year 1, and year 2 scores were obtained by using mean scores for -2 to two, ten to 14, and 22 to 26 months, respectively, to provide comparisons with annually measured variables.

Caregivers' anger was assessed on 24 items by using the Anger Expression Scale (Ax) (25). The Ax has three subscales that measure anger directed at others ("anger out"), anger directed at oneself ("anger in"), and anger control. Caregivers' depression symptoms were measured with the Global Distress Index of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item scale that is used to measure depression and that asks respondents to rate their moods and behaviors over the previous week (26). State anxiety was measured by using the 20 "state" items of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SAI) (27). All the caregiver measures have well-established reliability and validity, which have been previously described (3).

Caregivers' resources. Caregivers' social support was assessed with use of the 40-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) (28) and the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) (29). An overall ISEL score was derived by standardizing and summing the appraisal, belonging, tangible, and self-esteem subscales. The SSQ asks respondents to rate the number of relatives and other persons whom they could turn to for support in six situations and their degree of satisfaction with this support. SSQ scores were derived by summing the scores for satisfaction with relatives and satisfaction with others, standardizing each, and adding them together.

Caregivers' coping was assessed by using the Revised Ways of Coping Checklist (RWCCL) (30). The RWCCL has 57 questions and eight subscales: problem focused, seeks social support, blamed self, wishful thinking, avoidance, blamed others, count your blessings, and religiosity. Problem focused, seeks social support, and count your blessings were standardized and summed to form an active coping subscale; blamed self, wishful thinking, blamed others, and avoidance were standardized and summed to form a passive coping subscale.

Consumers' clinical status. Measures of consumers' clinical status were gathered at baseline by using methods and measures described previously (15,16). Diagnoses were assessed by clinicians with use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Psychotic Disorders Version (31). Positive symptoms were assessed by using the sum of the conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, unusual thought content, grandiosity, and suspiciousness items of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (32).

A negative symptoms score was calculated as the sum of the global ratings of affective flattening, alogia, avolition or apathy, anhedonia or asociality, and attention on the modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (mSANS) (33). Consumers' symptoms were measured monthly, and mean scores were calculated in an identical manner to scores for perceived stress. Hospitalization data were gathered from the mental health center at which all participants received outpatient services. These data were then dichotomized into two categories: clients who had been hospitalized during the year before randomization and for those who had not.

Data analysis

The analyses covered three periods: baseline, year 1 postrandomization, and year 2 postrandomization. Bivariate correlations were calculated between study variables, and the number of outcome variables was reduced by combining theoretically similar and highly correlated variables. Scores were standardized by setting means to 0 and standard deviations to 1, and composite variables were calculated as the mean of individuals' standardized scores. Repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were then performed on the primary caregiver outcome variables, with baseline caregiver outcomes and significant consumer clinical status variables entered as covariates to assess within- and between-group differences. Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of .05.

Results

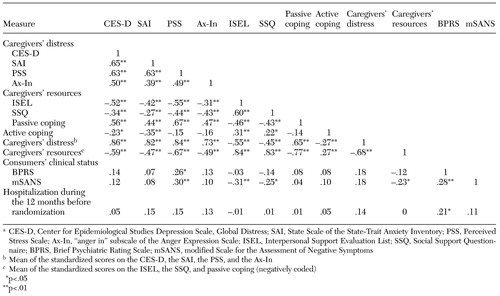

Correlations at baseline between the variables used as outcome variables are listed in Table 2. The two social support measures (ISEL and SSQ) were predictably highly positively correlated, whereas passive coping was negatively correlated with each. Because all three are related to the construct of "resources" analyzed by Dyck and colleagues (3), they were standardized, and a resource variable was formed from their mean (passive coping was negatively coded). Active coping was not included, because its correlation was somewhat lower than that of the other three variables. Similarly, because of the high correlations between severity of depression, anxiety, inwardly directed anger, and perceived stress and their conceptual congruence with distress, the four scales were standardized and averaged to form a "family caregiver distress" variable. Correlations between resources, distress, and the other study variables are also listed in Table 2.

Among study participants for whom 12- and 24-month outcome data were available, the caregivers of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment had significantly lower levels of baseline distress than the caregivers of persons who received standard psychiatric care (t=-2.6, df=64, p<.05). To control for these baseline differences, an ANCOVA was performed with baseline distress entered as a covariate. A between-subjects group effect was observed (F=6.6, df=1, 63, p<.05), which suggests that the caregivers of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment experienced significantly lower distress than those of consumers who received standard care. This difference remained significant when baseline resources and negative symptoms were entered as covariates (F=6.8, df=1, 60, p<.05). Mean difference scores between distress at baseline and year 1 were .17 for the standard care group and .02 for the multifamily-group treatment group and between baseline and year 2 were .09 for the standard care group and -.06 for the multifamily-group treatment group.

Data for participants who remained in the study at 24 months showed small differences in baseline resources, with caregivers of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment having greater resources than caregivers of consumers who received standard care, although these differences were not significant. Consequently, caregivers' resources at baseline were included as covariates in subsequent ANCOVAs. When baseline resources and negative symptoms were controlled for in a repeated measures ANCOVA, small group differences in caregivers' resources at 24 months were noted, but again these differences were not significant. These differences remained nonsignificant when baseline distress was also entered as a covariate.

It should be noted that because active coping was not included in the resources variable, it was entered as a covariate into each of the ANCOVAs mentioned above. Doing so did not meaningfully change the results of the analyses. No significant between- or within-group changes over time in active coping scores were found.

Discussion

Overall, multiple-family group treatment was shown to be beneficial to the psychosocial well-being of the family-member caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. After baseline distress and clinical status variables were controlled for, the distress of caregivers of clients who received multiple-family group treatment was substantially lower than that of caregivers of clients who received standard care, which lends support to our first hypothesis.

Our significant findings for caregivers' distress contrast with the nonsignificant results for caregivers' burden previously reported by McDonell and colleagues (11). Important differences in methods and measures may have resulted in the different findings. Most notably, the burden measure used by McDonell and colleagues, which consisted of numerous brief Likert scales to assess diverse areas of psychosocial functioning and caregiving, may have been insensitive to change. The measures of caregivers' distress used in the study reported here are established measures of psychological status and may be subject to less measurement error or greater sensitivity to change. Alternatively, although distress and subjective burden are conceptually related and empirically correlated within our data, multiple-family group treatment may actually work more directly on aspects of distress that are independent of the caregiving role and are thus less likely to be tapped by a measure of burden.

Because psychological distress and dysphoria have been associated with biological response modifiers and altered immunity (34,35,36) and have been implicated in poor health outcomes (3), multiple-family group treatment may also contribute to the long-term health of caregivers through distress reduction. Further research will be needed to clarify whether the effects of multiple-family group treatment are of sufficient magnitude and duration to exert a significant influence on caregivers' health outcomes.

Contrary to our second hypothesis, although the resources of participants in multiple-family group treatment were slightly greater than those of participants in the standard care group, the difference was not statistically significant. The reasons for this disparity are unclear. Data on resources were available for a smaller number of caregivers at 24 months than was the case for the distress analyses, which may have reduced the statistical power to detect differences between groups.

Alternatively, the measurement of resource variables may have been less relevant to the specific foci of action of the multiple-family group treatment. Although the measures have been shown to be highly reliable and valid, they may not have tapped the specific domains of resources that are affected by multiple-family group treatment. A similar issue may explain the null findings regarding active coping. For example, clinicians who conduct multiple-family group treatment attempt to model a problem-solving technique for family members and consumers throughout the intervention and attempt to increase social cohesion within treatment groups, thereby expanding the social network of participants. If measures of the impact of multiple-family group treatment on resources are directed more toward assessing caregivers' use of problem solving in everyday life and assessing the degree of continued contact with other participants in multiple-family group treatment, they may be more likely to elucidate a link between multiple-family group treatment and caregivers' resources that could then be investigated in future studies of distress outcomes.

It is also possible that multiple-family group treatment simply does not have an effect on the psychosocial resources of caregivers. The amount of time per month in which participants are involved in multiple-family group treatment is limited and may not be sufficient to allow for meaningful increases in social support, especially after allowance is made for substantial absenteeism. Moreover, as pointed out by McDonell and colleagues (11), multiple-family group treatment is designed to focus on consumers' illness management and recovery, not caregivers' psychological health. Thus modifications to the intervention, such as breakout groups designed to address assessment and improvement of caregivers' resources, may be necessary to positively affect the resources of family caregivers.

The analyses presented here do not give an indication of how multiple-family group treatment positively affects caregivers' distress. Because the results suggest that multiple-family group treatment does not have a meaningful impact on caregivers' resources, it is unlikely that such resources mediated the observed change in distress relative to that associated with standard psychiatric care. In other studies we found that multiple-family group treatment was associated with reduced negative symptoms and reduced use of psychiatric services after one year (15,16). However, it is unlikely that these factors account for much of the observed effect because of the very modest association of consumers' symptoms and caregivers' distress reported.

Another possibility is that multiple-family group treatment has a more complex effect on the family system of the primary caregiver. Magliano and colleagues (10) reported associations between the burden and coping strategies of primary caregivers and those of other relatives. Thus future studies of the mechanism of multiple-family group treatment may benefit from measuring variables related not only to the caregiver and the consumer but also to other persons involved in the lives of these two individuals. Finally, clinicians' adherence and competence may moderate the impact of multiple-family group treatment on caregivers. This issue is currently under study by our research group.

Additional factors limit the generalizability of the findings. First, caregivers of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment had marginally greater resources and less distress than those of consumers in the standard care group at baseline. Although study participants were randomly assigned to the two groups, which suggests that the groups should have been equivalent at baseline—and the covariates statistically controlled for these differences—replication without initial differences would lend additional support to the findings presented here.

Second, although a priori power analyses suggested that the original sample size was sufficient, the actual sample size was smaller because of attrition, which limited the power of longitudinal analyses. Finally, the sample was homogeneous in gender, race, and illness dimensions. Although the sample was representative of the typical outpatient with schizophrenia, the long illness duration of the consumers in the sample as a whole may have attenuated the results, as Martens and Addington (5) found that caregivers experience greater levels of distress during the first onset of schizophrenia. Thus the effects of multiple-family group treatment on caregivers who have had less time to adapt to life after diagnosis may be substantially different from those found in our sample.

Conclusions

Multiple-family group treatment appears to be successful in reducing the distress experienced by family-member caregivers, which in turn may have significant implications for caregivers' physical and psychological health and associated service needs. Corresponding increases in caregivers' resources and active coping were not supported by the data, which emphasizes the importance of determining the mechanism by which distress is reduced. Further research is needed to address measurement and methodologic issues related to the assessment of caregivers' resources as well as to evaluate possible mechanisms by which multiple-family group treatment affects the functioning of caregivers and other members of the consumers' family system.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant R01-52259 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Dyck (principal investigator).

At the time of this study, Mr. Hazel and Mr. Berry were affiliated with the Washington Institute for Mental Illness: Research and Training and Washington State University in Spokane. Mr. Hazel is currently with Pediatric Behavioral Health, National Jewish Medical and Research Center, in Denver, Colorado. Mr. McDonell, Dr. Short, Dr. Voss, Ms. Rodgers, and Dr. Dyck are with the Washington Institute for Mental Illness: Research and Training and Washington State University in Spokane. Mr. McDonell is also with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Texas-Houston Medical Center. Dr. Short and Dr. Dyck are also with Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington. Mr. Berry is with the department of psychology of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Send correspondence to Dr. Dyck at Eastern Branch, Washington Institute for Mental Illness: Research and Training, Washington State University, 310 North Riverpoint Boulevard, P.O. Box 1495, Spokane, Washington 99210-1495 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 97 consumers with schizophrenia and their caregivers

|

Table 2. Correlations between variables at baseline in a sample of 97 consumers with schizophrenia and their caregiversa

a CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, Global Distress; SAI, State Scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; Ax-In, "anger in" subscale of the Anger Expression Scale; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; SSQ, Social Support Questionnaire; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; mSANS, modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms

1. Hoenig J, Hamilton MW: The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 12:165–176, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Young HM, et al: Predictors of burden in spouse caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Psychology and Aging 6:392–402, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dyck DG, Short RA, Vitaliano PP: Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine 61:411–419, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Greenberg JS, Kim HW, Greenley JR: Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:231–241, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Martens L, Addington J: The psychological well-being of family members of individuals with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:128–133, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mors O, Sørensen LV, Therkildsen ML: Distress in the relatives of psychiatric patients admitted for the first time. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 85:337–344, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lowyck B, deHert M, Peeters E, et al: Can we identify the factors influencing the burden on family members of patients with schizophrenia? International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 5:89–96, 2001Google Scholar

8. Bibou-Nakou I, Dikaiou M, Bairactaris C: Psychosocial dimensions of family burden among two groups of carers looking after psychiatric patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:104–108, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Magliano L, Fadden G, Economou M, et al: Family burden and coping strategies in schizophrenia:1–year follow-up data from the BIOMED I study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:109–115, 2000Google Scholar

10. Magliano L, Fadden F, Fiorillo A, et al: Family burden and coping strategies in schizophrenia: are key relatives really different from other relatives? Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica 99:10–15, 1999Google Scholar

11. McDonell MG, Short RA, Berry CM, et al: Burden in schizophrenia caregivers: impact of family psychoeducation and awareness of patient suicidality. Family Process 42:91–103, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Noh S, Turner RJ: Living with psychiatric patients: implications for the mental health of family members. Social Science and Medicine 25:263–271, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. McFarlane WR: Multiple Family Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

15. Dyck DG, Hendryx MS, Short RA, et al: Service use among consumers with schizophrenia in psychoeducational multiple-family group treatment. Psychiatric Services 53:749–754, 2002Link, Google Scholar

16. Dyck DG, Short RA, Hendryx MS, et al: Management of negative symptoms among consumers with schizophrenia attending multiple-family groups. Psychiatric Services 51:513–519, 2000Link, Google Scholar

17. McFarlane WR, Link B, Dushay R, et al: Psycho-educational multiple family groups: four-year relapse outcome in schizophrenia. Family Process 34:127–144, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psycho-education in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679–687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Mueser KT, Sengupta A, Schooler NR, et al: Family treatment and medication dosage reduction in schizophrenia: effects on patient social functioning, family attitudes, and burden. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:3–12, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Stam H, Cuijpers P: Effects of family interventions on burden of relatives of psychiatric patients in the Netherlands: a pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal 37:179–187, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Chou KR, Liu SY, Chu H: The effects of support groups on caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. International Journal of Nursing Studies 39:713–722, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

23. McFarlane WR, Deakins SM, Gingerich SL, et al: Multiple-Family Psychoeducational Group Treatment Manual. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biosocial Treatment Division, 1999Google Scholar

24. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24:385–396, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Spielberger CD, Johnson EH, Russell SF, et al: The experience and expression of anger: construction and validation of an anger expression scale, in Anger and Hostility in Cardiovascular and Behavioral Disorders. Edited by Chesney M, Rosenman R. New York, Hemisphere, 1985Google Scholar

26. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R: Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI ("Self-evaluation Questionnaire"). Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1970Google Scholar

28. Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarch T, et al: Measuring the functional components of social support, in Social Support, Theory, Research, and Applications. Edited by Sarason IG, Sarason BR. Boston, Martenus Nijhoff & Dordrecht, 1985Google Scholar

29. Sarason IG, Pierce GR, Sarason BR: Social support and interactional process: a triadic hypothesis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 7:495–506, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Vitaliano P, Russo J, Carr JE: The Ways of Coping Checklist: revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavior Research 20:3–26, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders. New York, Columbia University, 1995Google Scholar

32. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Andreasen NC: The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

34. Greenberg AH, Dyck DG, Sandler LS: Opponent processes, neurohormones, and natural resistance, in Impact of Neuroendocrine Systems in Cancer and Immunity. Edited by Fox BH, Newberry BH. Toronto, Hogrefe,1984Google Scholar

35. Kiecolt-Glazer JK, Dura JR, Speicher CE, et al: Social caregivers of dementia victims: longitudinal changes in immunity and health. Psychosomatic Medicine 53:345–362, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Levy S, Herberman R, Lippmow M, et al: Correlation of stress factors with sustained depression of natural killer cell activity and predicted prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 5:348–353, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar