Antipsychotic Dosage at Hospital Discharge and Outcomes Among Persons With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Applying the schizophrenia treatment guidelines established by the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) project, this study evaluated whether antipsychotic medication dosage influenced patient outcomes in routine clinical settings. METHODS: The associations between discharge antipsychotic medication dosage and short-term clinical, social, and service use outcomes were observed in a sample of 246 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. RESULTS: Patients who were given high dosages of antipsychotic medication at hospital discharge (more than 1,000 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents) had greater severity of symptoms three months after discharge than patients who were given guideline-recommended dosages (300 to1,000 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents) (adjusted mean Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores of 45 and 39, respectively). Patients who were given low dosages of antipsychotic medication at hospital discharge (less than 300 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents) were less likely to report side effects (adjusted OR=.24) and slightly more likely to be nonadherent (21 percent of those within the recommended dose range compared with 39 percent of the those with low doses, not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction). No other differences related to medication dosage were observed in patient outcomes. CONCLUSIONS: Treatment that falls within antipsychotic medication dosage guidelines is associated with improvement in a limited, but critical, range of short-term patient outcomes in routine clinical settings.

Most definitions of optimal treatment for patients with schizophrenia assign a central role to appropriate antipsychotic medication dosage (1,2,3,4,5). Data from controlled trials indicate that, above a certain threshold, higher antipsychotic dosages generally increase the occurrence of side effects without contributing to clinical improvement (6) and may increase the likelihood that the patient will leave the hospital against medical advice (7).

Drawing on this science base, the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) project formulated guidelines for antipsychotic dosage. According to these guidelines, the recommended dosage range for an acute symptom episode is 300 to 1,000 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents per day for a minimum of six weeks, and the minimum effective dosage should be used (8). Although not intended to replace informed clinical judgment or undermine the patient's role in treatment decisions, guidelines aim to synthesize essential information, reduce inappropriate variability in treatment practices, and improve patient outcomes (9). Furthermore, the existence of practice guidelines means that researchers can adopt a precise and objective standard in evaluations of treatment patterns rather than relying on ad hoc or comparative standards to define high and low medication dosages.

The PORT's antipsychotic dosage recommendations are based on extensive clinical trial research. However, limited data are available on whether these recommendations are associated with more effective care for patients who have schizophrenia (10). In clinical settings, many factors related to the patient, the provider, and the treatment setting influence dosage decisions, but these influences are minimized in the clinical trial design. Thus the correlation of dosage variations with patient outcomes in clinical settings is unclear.

A recent cross-sectional study based on the original PORT project sample showed that patients who were treated with low dosages of conventional antipsychotics had better role functioning than patients who received higher dosages (11). Another study showed that patients for whom oral antipsychotic medications were prescribed at dosages within the PORT guideline range had lower severity of symptoms at six-month follow-up than patients who received low or high dosages (12), but other outcome domains that are important to quality of life were not evaluated. There are no longitudinal data available about the possible impact of antipsychotic medication dosage on a range of patient outcomes. Addressing this research gap is germane to promoting standardized treatment guidelines that inform patients' and clinicians' expectations.

Using a heterogeneous sample of patients with schizophrenia, we examined whether antipsychotic medication dosages, as defined by PORT guidelines, were associated with short-term clinical status, social and occupational functioning, and use of mental health services. Data for this study were collected before the publication of the PORT study and therefore do not reflect factors that may be associated with clinicians' proclivity to adhere to treatment guidelines.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected as part of the Rutgers Hospital and Community Survey, 1995-1997, which has been described fully elsewhere (13). The study was approved by Rutgers University's institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from participants. Consecutively admitted inpatients with clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were eligible to participate in the study if they spoke English, were enrolled in or eligible for Medicaid, were aged 18 to 64 years, lived locally, and had no severe or disabling medical conditions. Patients were excluded if they did not meet diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, had a hospital stay of more than 120 days, were discharged against medical advice or to another inpatient psychiatric facility, or were otherwise unable to complete a baseline assessment. The final study sample consisted of 315 patients.

A total of 264 patients (84 percent of the final sample) completed the three-month follow-up interview. Data on discharge medication dosage were available for 246 patients; two patients did not receive a prescription for antipsychotic medication at discharge, and discharge dosage data were missing from the charts of 16 patients. The patients with missing data did not differ significantly (p>.10) from the final sample in age, gender, race, number of previous hospitalizations, and admission antipsychotic dosage.

Assessments

Within three days of discharge, the study patients were interviewed by clinically experienced, trained research staff. Primary psychiatric diagnoses were made by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R updated for DSM-IV (14). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview was used to make DSM-IV diagnoses of depression and substance abuse or dependence (15,16). Clinical symptoms were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (17) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (18). Depressive symptoms were also measured by using the Beck Hopelessness Scale (19). Social engagement was assessed with a four-item scale derived from the schizophrenia PORT project that measured frequency of interactions with friends (10). Quality of life was assessed with a scale derived from the Quality of Life Interview (20). Occupational functioning was assessed by asking patients whether they were employed at least part-time or were seeking employment. Patients were also asked about their history of psychiatric hospitalization.

Demographic information, admission status (voluntary or involuntary), and data on the type, dosage, and route of administration of discharge medications were obtained from chart reviews. A research assistant, blinded to the results of the structured assessment, reviewed each patient's hospital record to determine the discharge antipsychotic dosage regimen. Both oral and depot antipsychotic medication dosages were converted to chlorpromazine milligram equivalents (21,22,23). Although conversion factors for depot medications may be less precise, depot medications were commonly used and thus were included in this analysis. Because there is also controversy about conversion factors for newer-generation antipsychotic medications, we conducted supplementary analyses in which the few patients who were given these medications were excluded. The results remained essentially the same (data not shown).

The patients were reinterviewed three months after discharge by using the same instruments. Patients were also asked about the presence and severity of side effects of medications and how well they adhered to the prescribed medication regimen. Patients were considered to be nonadherent if they reported not taking a scheduled oral antipsychotic medication or changing the dosage without a doctor's advice during the two weeks before the interview or if they stopped taking the medication for a week or more during the previous three months. Patients who were taking depot medications were considered to be nonadherent if they missed one or more scheduled injections during the three months after hospital discharge. Self-reported rehospitalization data were supplemented with information from Medicaid claims, and rehospitalizations reported from either of these sources were considered in our analyses.

Data analysis

Patients were categorized into three groups based on the prescribed antipsychotic dosage at hospital discharge: recommended dosage (300 to 1,000 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents), high dosage (more than 1,000 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents), or low dosage (less than 300 chlorpromazine milligram equivalents). Treatment guidelines that informed this dosage categorization were not published at the time the patients in this study were being treated.

The three groups were compared on factors other than dosage that might influence three-month outcomes, including demographic characteristics (gender, age, and race), clinical variables (previous hospitalization, baseline severity of symptoms, and comorbid conditions), and treatment characteristics (hospital and antipsychotic medication class and route of administration). Statistical significance was assessed with t tests and chi square tests.

Linear and logistic regression analyses were used to examine whether patients for whom antipsychotic dosages outside the recommended ranges were prescribed (either low or high) had significantly different outcomes from patients for whom recommended dosages were prescribed, adjusting for the demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics described above. Outcomes measured included clinical functioning (BPRS summary score, CES-D depression, hopelessness, perceived medication side effects, and medication nonadherence), social and occupational functioning (social engagement, quality of life, and employment), and service use during the follow-up period (rehospitalization and emergency department use). Unadjusted and adjusted regression coefficients and their statistical significances are reported. The Bonferroni method (24) was used to adjust statistical significance tests for multiple comparisons (p=.05 divided by ten main comparisons).

Results

Discharge antipsychotic dosages within the recommended range were prescribed to 161 patients (65 percent), high dosages to 50 patients (20 percent), and low dosages to 35 patients (14 percent).

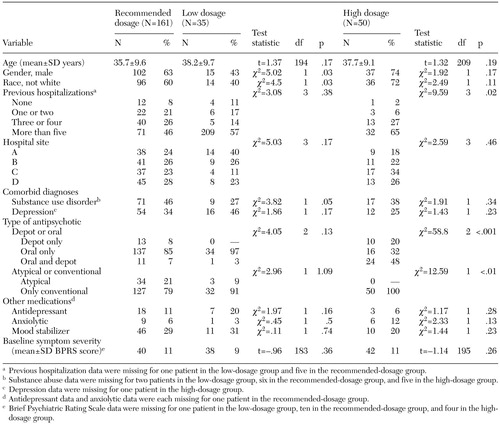

Demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of the three groups are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the group who received recommended dosages, the patients who received high dosages were more likely to have at least five previous hospitalizations (46 percent compared with 65 percent) and were about seven times as likely to receive both oral and depot medications. Furthermore, none of the patients in the high-dosage group received a newer-generation antipsychotic medication, compared with 21 percent in the recommended-dosage group.

Patients in the low-dosage group were more likely than those in the recommended-dosage group to be female and white and were less likely to have a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence. It is noteworthy that discharge BPRS scores and depression measures did not differ significantly among the three groups. Because medication dosages were not randomly assigned, it is possible that patients were given the prescribed dosages specifically to achieve this similar discharge clinical status.

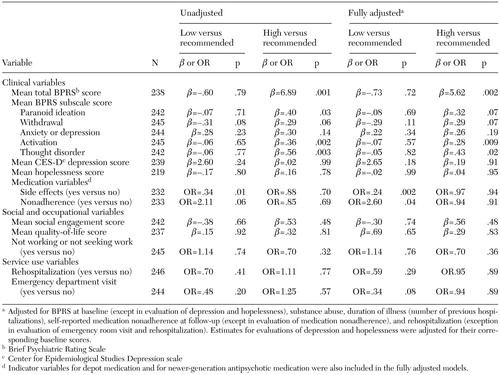

The relationship between discharge dosage and outcomes is shown in Table 2. Bivariate comparisons between dosage level and the central variables of interest are shown, as well as comparisons that have been adjusted for baseline severity of symptoms and demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics.

Patients who received high dosages had significantly higher BPRS scores at follow-up than those who received dosages within the recommended range (Table 2). These differences were found in two of the five BPRS subscales—activation and thought disorder—although the adjusted results were not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction. Because atypical antipsychotics were used more frequently among patients who received recommended dosages, we adjusted for this in a post hoc analysis. The result was the same (adjusted beta for BPRS score=6.33, p=.001, data not shown). Those assigned high dosages did not differ significantly from those assigned recommended dosages in other clinical outcomes, social and occupational functioning, or service use.

Patients for whom low dosages were prescribed were less likely to report side effects and more likely to be nonadherent to their medication regimen over the follow-up period (not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction; Table 2). Comparisons between the low-dosage and recommended-dosage groups indicated no other significant differences in clinical symptoms, social and occupational functioning, or service use outcomes after three months.

Discussion and conclusions

Applying the antipsychotic medication dosage framework from the PORT guidelines, this study documented a limited number of short-term differences in clinical outcomes between patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders for whom recommended antipsychotic medication dosages were prescribed at hospital discharge and those for whom either low or high dosages were prescribed. However, no evidence was found of differences in social and occupational functioning or service use by these dosage categories.

Consistent with the results of previous research (12), patients who received high medication dosages had greater exacerbation of symptoms at follow-up than patients who received recommended dosages, even after adjustment for baseline severity and other clinical, demographic, and treatment variables. This finding indicates that high medication dosages do not necessarily lead to a quicker, more effective resolution of psychotic symptoms. Unmeasured clinical characteristics may have differentiated patients who were prescribed high dosages from other patients in this observational study (25,26,27). It appears that prescribing high dosages does not necessarily address these differences.

It is theoretically possible that the elevated severity of symptoms in the high-dosage group reflects elevated side effect profiles. Increased sedation due to side effects can be difficult to distinguish from negative symptoms (28). Untreated akathisia may result in agitation. However, if sedation and agitation were responsible for the elevated symptom severity scores, this pattern should have been confined largely to the social withdrawal and activation subscales. Instead, elevated scores were found on the thought disorder subscale also, indicating that higher symptom severity scores at follow-up are unlikely to simply reflect side effects of medications.

We found no association between low dosage and greater severity of symptoms. The three-month follow-up period might have been too short to enable detection of the negative clinical effects of maintaining patients on a low dosage that were reported in a study in which patients were followed up for six months (12). Despite this lack of difference in severity of symptoms at follow-up, patients in the low-dosage group were slightly less likely to be adherent to medication regimens during follow-up and reported significantly fewer side effects. Typically, adherence to medication regimens is thought to decrease when patients have a greater perception of side effects or poor perceptions of symptom improvement (29). Perhaps our finding differed from this expectation because the patients who received low dosages improved and thought that their medication was not necessary. A decision to lower antipsychotic dosage may also result from patient-psychiatrist negotiations involving patients who are prone to nonadherence.

Antipsychotic medication dosage did not influence any of the other outcome domains—social and occupational functioning and service use—among patients in this study. It is possible that the selected measures did not capture the important variation in these outcomes. It is also possible that adherence to dosage guidelines alone may not result in consistent or strong effects on these outcomes (11), because these outcomes are generally associated with a complex interplay among social context, availability of resources, and treatment decisions in addition to medication use (30). There is a growing body of literature on the greater impact of newer versus conventional antipsychotics on psychological and employment outcomes (31,32). Thus future studies—based on samples with greater exposure to newer antipsychotics—may better define relevant measures and identify beneficial effects of medication dosage related to these domains. This study has documented how conventional medications influence patient outcomes in clinical settings and has provided a benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness of the newer medications.

Previous reports of variations in physician prescribing patterns related to antipsychotic medications (11,33,34) emphasized the need to improve guideline implementation. The results of the study reported here highlight an additional need to develop quality assurance guidelines that specify a broader array of desired outcomes that cross several treatment domains simultaneously—for example, medication management, residential placement, and continuous outpatient care. Understanding why psychiatrists deviate from recommended dosages also needs exploration.

Our study was limited by our inability to examine the full range of explanations for the observed associations between medication dosage and patient outcomes. The study's nonrandomized design made it impossible to control fully for factors that might inform dosage decisions and explain patient outcomes. For example, the fact that we did not find differences in some outcomes may indicate that clinicians and patients correctly weigh the importance of medication dosage and other factors in achieving treatment goals.

In addition, the sample was limited in size and consisted of patients who had substantial treatment histories. Dosage information was not available for the follow-up period. Some dosage adjustment may occur in outpatient clinics, but it is reasonable to assume that the discharge medication dosage has effects over a three-month follow-up period. To the extent that most outpatient dosage adjustment moves dosages closer to the recommended range, it is likely that our results underestimate the impact of dosages outside of the recommended range. Further research is needed to determine whether inpatient and outpatient practitioners follow different medication prescription patterns and how these two sectors coordinate their prescribing patterns.

This is an encouraging period in the development of antipsychotic medications. Failure to understand the impact of dosage will inevitably diminish the effectiveness of both conventional and newer-generation antipsychotics on patients' quality of life. Further research is needed to assess the impact of treatment interventions, including pharmacologic practice guidelines, on the several domains of patient outcomes.

Dr. Sohler is affiliated with the department of epidemiology and population health of Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York. Dr. Walkup, Dr. McAlpine, Dr. Boyer, and Dr. Olfson are affiliated with the Institute of Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Dr. McAlpine is also with the department of health services research and policy of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Dr. Olfson is also with the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the department of psychiatry of Columbia University in New York City. Send correspondence to Dr. Sohler at Montefiore Medical Center, Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, 111 East 210th Street, Bronx, New York 10467 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 246 patients with schizophrenia by level of dosage of antipsychotic medication at hospital discharge

|

Table 2. Three-month outcomes for 246 patients with schizophrenia by level of dosage of antipsychotic medication at discharge

1. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia: American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1–45, 2000Link, Google Scholar

2. McEvoy J, Weiden P, Smith T, et al (eds): The Expert Consensus Series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):1–58, 1996Google Scholar

3. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611–617, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Osser DN, Sigadel R: Short-term inpatient pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 9:89–104, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fenton WS, Kane JM: Clinical challenges in the psychopharmacology of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:563, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McEvoy J, Haughty G, Steingard S: Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia: a controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:739–745, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Van Putten T, Marder S, Mintz J: A controlled dose comparison of haloperidol in newly admitted schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:754–758, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mellman TA, Miller AL, Weissman EM, et al: Evidence-based pharmacologic treatment for people with severe mental illness: a focus on guidelines and algorithms. Psychiatric Services 52:619–625, 2001Link, Google Scholar

10. Lehman A, Steinwachs D: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia patient outcome research team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Zito, JM, et al: The schizophrenia PORT pharmacological treatment recommendations: conformance and Implications for symptoms and functional outcome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:63–73, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Owen RR, Thrush CR, Kirchner JE, et al: Performance measurement for schizophrenia: adherence to guidelines for antipsychotic dose. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 12:475–482, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Boyer CA, Olfson M, Kellermann SL, et al: Studying inpatient treatment practices in schizophrenia: an integrated methodology. Psychiatric Quarterly 66:293–320, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, patient edition (SCID-P, version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1990Google Scholar

15. Sheehan D, Janavs J, Baker R, et al: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Clinician Rated, Version 3.0. Tampa, Fla, University of South Florida, 1993Google Scholar

16. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 20):20–33, 1998Google Scholar

17. Overall JE, Gorham DP: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–807, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Beck A, Weissman A, Lester D, et al: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:861–865, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Lehman A: A Quality of Life Interview for the Chronically Mentally Ill: Shortened Version. Baltimore, University of Maryland, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, 1992Google Scholar

21. Kane JM: Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 334:34–41, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Zito JM: Psychotherapeutic Drug Manual, 3rd ed. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

23. Schulz P, Rey MJ, Dick P, et al: Guidelines for the dosage of neuroleptics: II. changing from daily oral to long-acting injectable neuroleptics. International Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 4:105–114, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Grove WM, Andreasen NC: Simultaneous tests of many hypotheses in exploratory research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 170:3–8, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Munetz M, et al: Dose of fluphenazine, familial expressed emotion, and outcome in schizophrenia: results of a two-year controlled study. Archive of General Psychiatry 45:797–805, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Andrews P: Hall JN, Snaith PR: A controlled trial of phenothiazine withdrawal in chronic schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 128:451–455, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Prien RF, Levine J, Switalski RW: Discontinuation of chemotherapy for chronic schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 22:20–23, 1971Google Scholar

28. Harrow M, Yonan CA, Sands JR, et al: Depression in schizophrenia: are neuroleptics, akinesia, or anhedonia involved? Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:327–238, 1994Google Scholar

29. Kampman O, Lehtinene K: Compliance in psychoses. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:167–175, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Rabinowitz J, Modai I, Inbar-Saban N: Understanding who improves after psychiatric hospitalization. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:152–158, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Hamilton SH, Edgell ET, Revicki DA, et al: Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a comparison of olanzapine and haloperidol in a European sample. International Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 15:245–255, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Emsley RA: Partial response to antipsychotic treatment: the patient with enduring symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 23):10–13, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

33. Chen RS, Nadkarni PM, Levin FL, et al: Using a computer data base to monitor compliance with pharmacotherapeutic guidelines for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:791–794, 2000Link, Google Scholar

34. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Use of pharmacy data to assess quality of pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia in a national health care system: individual and facility predictors. Medical Care 39:923–933, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar