Interest in Psychiatric Advance Directives Among High Users of Crisis Services and Hospitalization

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study examined rates of interest in creating psychiatric advance directives among individuals at risk of psychiatric crises in which these directives might be used and variables associated with interest in the directives. METHODS: The participants were 303 adults with serious and persistent mental illnesses who were receiving community mental health services and who had experienced at least two psychiatric crises in the previous two years. Case managers introduced the concepts of the directives and assessed participants' interest. The associations between interest in the directives and demographic characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, level of functioning, diagnosis, history of hospitalizations, history of outpatient commitment orders, support for the directives by case managers, and site differences were examined. RESULTS: Interest in creating a directive was expressed by 161 participants (53 percent). Variables significantly associated with interest were support for the directives by a participant's case manager and having no outpatient commitment orders in the previous two years. Reasons for interest included using the directives in anticipation of additional crises and as a vehicle to help ensure provision of preferred treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Substantial interest in psychiatric advance directives was shown among individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. The results strongly suggested that attitudes of clinicians about psychiatric advance directives are associated with interest in the directives among these individuals. Therefore, it is important to educate clinicians and address their concerns about the directives so that they can more comfortably support creating the documents. A shift in values may also be necessary to more consistently recognize and honor patients' treatment preferences as specified in the directives.

Psychiatric advance directives are an emerging method of treatment planning for adults with serious and persistent mental illness (1,2,3). The directives document preferences in advance of acute symptoms that may compromise the capacity for decision making. Instructions in the directives may include preferences about medications, electroconvulsive therapy, restraint and seclusion, hospitals, alternatives to hospitalization, and persons to contact about care of patients' dependents and household (4,5,6,7). Individuals may also appoint in the directive an "agent" or attorney-in-fact, who has legal authority to make treatment decisions that are consistent with instructions contained in the directive (8).

Psychiatric advance directives have been promoted by professional, self-help, and advocacy organizations, and nearly all states have either specific statutes about the directives or statutes concerning advance directives for general health care that are considered to cover psychiatric advance directives (1,9,10,11,12,1314,15). Supporters of the directives believe that their use may improve services and outcomes for service recipients. Foremost, the directives provide a mechanism for individuals to have their voice heard during mental health crises, when they are least likely to have meaningful participation in treatment decisions (16,17). Such participation can enhance treatment self-efficacy and responsibility, collaboration and respect in the treatment relationship, and clinical outcomes (3,18,19,20,21). The directives can also support planned, effective crisis treatment by identifying resources to deescalate crises and to serve as alternatives to hospitalization. These efforts may, in turn, reduce hospitalizations, court proceedings, and costs (3,7,19,20,21,22,23).

Despite these potential benefits, some of the most basic questions about psychiatric advance directives remain unanswered. In particular, we know little about how many and which individuals are interested in creating the directives and why they are interested. The limited literature suggests that a substantial proportion of service recipients may be interested in creating these documents. In one study, 62 of 93 outpatients (67 percent) surveyed at a community mental health center responded that they would want to complete a psychiatric advance directive if shown how to create one (24). In another study, 30 of 40 outpatients (75 percent) were interested in preparing a directive; greater interest was shown by women and those with previous hospitalizations (16). In a London study, 42 (40 percent) of 106 individuals with psychotic disorders and at least one previous hospitalization were interested in creating a "crisis card," which is similar to a psychiatric advance directive. Greater interest was shown by persons who were white, had affective disorders, and had had fewer hospitalizations (25).

No research has systematically studied individuals receiving mental health services to determine rates of interest in psychiatric advance directives or has systematically evaluated the clinical, demographic, and contextual variables associated with interest. It is especially valuable to assess the extent of interest in psychiatric advance directives among persons at high risk of having crisis episodes that trigger the use of the directives, because these individuals are the most likely to need, use, and benefit from the documents.

Our study determined rates of interest in and factors associated with interest in creating psychiatric advance directives among persons who were at high risk of mental health crises as judged from a history of crisis service and hospital use. We examined variables associated with interest in the directives found in previous research, including demographic characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, level of functioning, diagnosis, and history of hospitalization. In addition, we examined outpatient commitment orders, because the directives have been posed as a potentially less coercive alternative, suggesting that individuals with a history of outpatient commitment orders may be particularly interested in creating the directives (3,26). We also examined case managers' support for psychiatric advance directives, because case managers introduced concepts about the directives to study participants and therefore could affect their interest in the documents. Finally, we examined differences between sites in participants' rates of interest in the directives, because organizational values and characteristics may influence interest in mental health innovations such as the directives (27).

Methods

Participants

The participants were adults enrolled in services in two community mental health centers in two counties in Washington State. Recruitment procedures and consent forms were approved by the University of Washington's institutional review board. Participants were selected as part of a larger study about implementation of psychiatric advance directives.

To be eligible, individuals had to be at least 18 years old, to have had at least two psychiatric emergency department visits or hospitalizations during the previous two years, and to be able to participate in research interviews in English. On the basis of the criteria of age and service use, 475 potentially eligible individuals were identified from electronic records in the two participating agencies.

Of potentially eligible individuals, 158 could not be contacted, 12 were either unable to provide informed consent or unable to participate in interviews in English, and two were considered too agitated to be approached about participation. The remaining 303 persons were considered eligible for participation.

Instruments and data collection

Data collection occurred between January 2001 and March 2002.

Interest in psychiatric advance directives. Case managers assessed interest in the directives among eligible individuals with a structured introduction to key concepts about the directives. The introduction noted that psychiatric advance directives include a listing of treatment preferences, give the individual an opportunity to have a say in treatment decisions, and are completed when psychiatric symptoms are not acute. If a participant was not interested, the case manager asked an open-ended question about reasons for lack of interest. Verbatim responses were documented, and the information, stripped of participant identifiers, was given to the study team. Participants interested in creating a directive were asked for permission to release their contact information to the study team. The study team obtained informed consent and then asked participants an open-ended question about reasons for interest in the directives. Verbatim responses were again documented.

Independent variables. For each participant, demographic characteristics—age, ethnicity, and gender—as well as diagnosis, score on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (28), and number of hospitalizations and outpatient commitment orders in the previous two years were obtained from electronic records of the participating agencies. Ethnicity was dichotomized as white or nonwhite because of the small proportion of several of the groups of nonwhite participants. Of the 303 participants, 219 (72 percent) were white. Of the 84 nonwhite persons (28 percent), 55 (65 percent of the nonwhite group) were African Americans, 12 (4 percent) were Asians or Pacific Islanders, nine (3 percent) were Native Americans, six (2 percent) were Hispanics, and two (.7 percent) were from other ethnic groups. Primary axis I diagnoses were placed in four categories: schizophrenia spectrum, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other diagnoses. Hospitalizations and outpatient commitment orders were dichotomized as 0 or ≥1 because of skewed distributions. Recruitment site was also identified.

Symptom severity and level of functioning were assessed with the Problem Severity Summary (PSS), a 13-item instrument designed for community mental health treatment planning and performance monitoring. The PSS has shown adequate internal consistency, sensitivity to treatment change, and concurrent, predictive, and discriminant validity (29).

Case managers rated themselves on support for the concepts of psychiatric advance directives before introducing the information about the directives to the participants. The case managers answered a four-question scale with Likert scoring (negative-to-positive scale), created for the study: How useful do you think psychiatric advance directives would be for consumers during mental health crises? How useful do you think psychiatric advance directives would be for service providers during mental health crises? How do you feel, personally, about psychiatric advance directives? How useful would it be for consumers to have service providers to help them complete psychiatric advance directives? The scale has adequate internal consistency (coefficient alpha=.79).

Statistical analyses

Narrative responses to open-ended questions about interest in psychiatric advance directives were coded by conceptual category by the first author and independently by one of the coauthors. Discrepancies in coding were discussed until agreement was reached. Reasons for interest or lack of interest in the directives are reported here, along with rate of interest.

To determine quantitative variables associated with interest in the directives, we analyzed differences between the participants whose data were used in the analyses and the 46 participants (15 percent) whose data were not used because of missing case manager data. Bivariate associations were then used to examine differences between participants who were and those who were not interested in creating the directives. To determine the best set of independent variables associated with interest, logistic regression analyses were conducted for the variables that were statistically significant (p<.05) in the bivariate analyses. To better understand the results, and to calculate meaningful odds ratios (ORs) and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs), variables with significant associations were recoded, and the logistic regression was recalculated.

Results

The study sample of 303 included 152 women (50 percent) and 84 nonwhite persons (28 percent). The mean±SD age of the sample was 42.5±10.5 years. The primary axis I psychiatric diagnoses for the participants were schizophrenia spectrum disorders (155 patients, or 51 percent), major depression (61 patients, or 20 percent), bipolar disorder (77 patients, or 25 percent), and other diagnoses (ten patients, or 3 percent). The mean± SD GAF (28) score was 31.1±8.5, indicating major impairment in several areas of functioning.

Rate of and reasons for interest

Of the 303 participants, 161 (53 percent) expressed interest in creating a psychiatric advance directive. Of this group of 161 participants, 132 (82 percent) answered the open-ended question about the reasons for their interest. Some participants provided more than one reason. A total of 163 reasons were cited. Thirty-five participants (27 percent) reported a case manager's suggestion that the participant create a psychiatric advance directive, and 36 (27 percent) reported their general belief that a psychiatric advance directive would be helpful. A total of 22 participants (17 percent) reported wanting to avoid repeating previous negative treatment experiences; 16 (12 percent) wanted monetary compensation from the study; 14 (11 percent) were simply curious about the directives; 13 (10 percent) wanted to have input into, a say in, or control over their treatment; and 11 (8 percent) wanted a plan for future incapacity.

Of the 142 participants who were not interested in psychiatric advance directives, 96 (68 percent) specified a reason. A total of 96 reasons were given. Despite attempts to design the introductory script to separate interest in the directives from interest in the broader study about the directives, 21 participants (22 percent) reported concerns about research participation. A total of 18 persons (19 percent) denied having a mental illness or the potential for future crises that would warrant a psychiatric advance directive, 16 (17 percent) reported already having sufficient plans for crisis treatment, 12 (13 percent) reported not having the time to create a psychiatric advance directive, and six (6 percent) believed that having a psychiatric advance directive would not affect treatment.

Factors associated with interest

Data about case managers' support for the directives were missing for 46 of the 303 participants, and these individuals were not included in the analysis of factors associated with interest, leaving 257 participants with complete data on all key variables. Participants whose data were used in the analyses did not differ from those whose data were not used with respect to age, ethnicity, primary axis I diagnosis, and GAF score. However, those lacking case manager data were more likely to be women (χ2=4.9, df=1, p=.03).

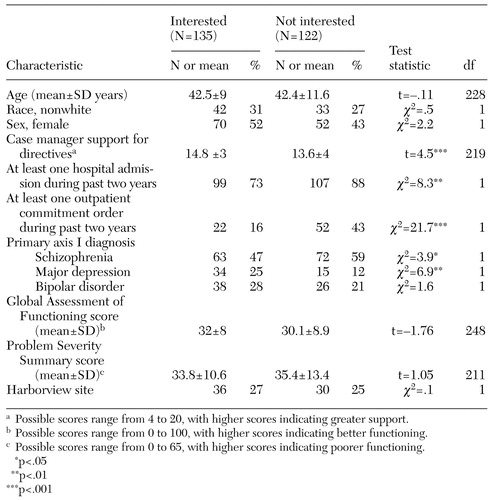

Bivariate analyses showed that several factors were positively related to interest in creating a psychiatric advance directive: the case manager's support for directives, having major depression, not having schizophrenia, and having no hospitalizations or outpatient commitment orders in the previous two years. Variables not significantly related to interest were age, GAF score, PSS score, ethnicity, gender, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and agency, as can be seen in Table 1.

On the basis of these bivariate analyses, five variables were entered into a logistic regression model for interest in psychiatric advance directives: any hospital admission, any outpatient commitment order, a primary axis I diagnosis of major depression, a primary axis I diagnosis of schizophrenia, and case manager's support for psychiatric advance directives. In the results of the logistic regression, the only variables that were positively associated with participants' interest in the directives were having no previous outpatient commitment orders (Wald's t=11.69, df=1, p<.001) and having a case manager who supported psychiatric advance directives (Wald's t=15.44, df=1, p<.001). To test the validity of these relationships, we fit models using stepwise techniques, both forward and backward. The same two variables were significant in all models.

Then, to best summarize the model, the two significant variables associated with interest were recoded, and the model was refit. Having an outpatient commitment order was reverse coded, and the case manager support scale was dichotomized at the median, 14.0. The logistic regression model showed that participants with case managers whose ratings were above the median on support of psychiatric advance directives were more than twice as likely to be interested in creating a directive as were participants whose case managers' ratings were below the median on support (Wald's t=8.64, df=1, p=.003; OR=2.20, 95 percent CI=1.30 to 3.73). In addition, participants with no outpatient commitment orders were almost four times as likely to be interested in creating a directive as participants with a history of at least one outpatient commitment (Wald's t= 20.04, df=1, p<.001; OR 3.87, 95 percent CI=2.14 to 6.99).

Discussion and conclusions

More than half (53 percent) of our sample of outpatients with histories of repeated use of crisis services and hospitalization expressed interest in creating a psychiatric advance directive. Individuals with this history are at risk of future mental health crises and therefore have the greatest need for methods of advance crisis planning such as directives. We found a slightly lower rate of interest in psychiatric advance directives than did previous surveys of outpatients who were not selected on the basis of high use of crisis services (16,24), but a somewhat higher rate than a study with a sample similar to ours in which interest in executing "crisis cards" was assessed (25). Given these findings, we believe that our results are likely to be representative of interest in psychiatric advance directives among persons who have a history of psychiatric crises.

In our study, in contrast with previous research, demographic characteristics were not significantly related to interest in psychiatric advance directives. It could be that previous research confounded ethnicity with socioeconomic status or education level, both of which were low and had little variation in our sample. Diagnosis was significantly associated with interest in the directives, but only in the bivariate analyses. Our study was consistent with one earlier study with a comparable sample, selected for previous hospital use (25), in that having major depression and having fewer hospitalizations were associated with interest in psychiatric advance directives. However, in a study with a broader sample, greater interest in the directives was associated with having had at least one recent hospitalization (16).

Logistic regression showed that case managers' support of psychiatric advance directives and participants' having no previous outpatient commitment orders were significantly associated with interest in the directives. In post hoc analysis we also found a significant positive correlation between case managers' support for the directives and the proportion of case managers' caseloads of patients who expressed interest in the directives (r=.34, p<.01). In addition, in narrative responses, the most commonly cited reason for interest in the directives was case managers' suggesting the directives. These results strongly suggest that clinicians' attitudes about psychiatric advance directives influence service recipients' interest in the documents when the clinicians are responsible for introducing the directives to patients.

Contrary to our expectation, having any outpatient commitment orders was inversely related to interest in psychiatric advance directives. It could be that service recipients do not view the directives as a potential substitute for outpatient commitment orders in the way that researchers and policy makers have viewed them. Certainly, to the extent that the directives remain consumer-directed documents, voluntarily created, they cannot be used to leverage treatment in the same manner as court-ordered outpatient commitment. Alternatively, it could be that having an outpatient commitment order serves as a proxy for other unmeasured variables, such as treatment engagement, adherence, or appreciation that one has a mental illness. Outpatient commitment is unlikely to serve as a proxy for impairment, because our results and post hoc analyses did not show a significant association of the GAF score or the PSS score with interest in psychiatric advance directives.

The data suggest that individuals with arguably great need for the directives—those with schizophrenia, multiple hospitalizations, and outpatient commitment orders—are less interested in the directives than others with severe and persistent mental illness. However, as noted above, in multivariate analyses, the importance of diagnosis and hospitalizations were overshadowed by outpatient commitment orders, suggesting that the relationship of diagnosis and hospitalizations to individuals' lack of interest in the directives may instead be a function of disengagement from voluntary outpatient treatment. For those who discount the need for treatment, psychiatric advance directives will predictably be of little interest, except possibly as a vehicle for refusing future treatment. The directives may be valuable only to individuals who perceive value in the treatment that the documents direct. However, although the directives may not be appealing to everyone who could benefit from them, our study confirmed interest in the directives by a majority of individuals at risk of future crises. If the hypothesized benefits of the directives are supported empirically, interest in them may increase.

Our findings must be interpreted within the limitations of the study. First, we were only partially successful in differentiating interest in the directives themselves from interest in participating in research about them, and our results may therefore somewhat underestimate actual rates of interest in the directives. Second, our selection of individuals who had had repeated previous crises and hospitalizations and who were also receiving outpatient services limited our ability to generalize results to a broader population. Third, some potentially important variables, such as socioeconomic level, education, treatment adherence, organizational culture, and service system characteristics, were not examined. Finally, it should be noted that not everyone who expresses interest in creating a psychiatric advance directive will ultimately create one—for a variety of reasons, which may include difficulty in navigating complex legal information, lack of a simple form for the directive, and lack of assistance in completing it.

Despite these limitations, the findings are relevant to the implementation of psychiatric advance directives in public mental health systems. These directives have the potential to improve treatment involvement and outcomes for patients (2,3,21) and reduce hospitalization and service costs (7,19-22). Even if only a few of these benefits are realized, introducing individuals to psychiatric advance directives is worthwhile, given the substantial rate of interest in the directives among persons who are likely to have frequent crises in which the documents could be used. Our findings suggest that introduction to and training about the directives can be fruitfully focused on this population.

Our findings also make clear that clinicians' attitudes about psychiatric advance directives influence interest among service recipients. Although many participants were interested in creating the directives to increase the likelihood that preferred treatment would be received, some felt that the documents would have little actual effect on treatment decisions. Therefore, an important step in implementing the directives is to educate clinicians about the directives and address clinicians' concerns about them. Clinicians will then be able to more comfortably support the directives (10). Although this step is important, a true shift in values about how treatment is conducted is also necessary if clinicians are to fully support the directives. For the documents to be used and to be effective, clinicians must recognize and honor the treatment preferences specified by service recipients. This stance, although often preached, is not always practiced, particularly during crisis episodes experienced by persons with severe and persistent mental illness. It is this shift in values that may be the most critical to encouraging interest in and successful use of psychiatric advance directives.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-MH58642-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Patricia Backlar, Ph.D., Robert Fleischner, J.D., John LaFond, J.D., David Lord, J.D., Jeff Swanson, M.D., and Marvin Swartz, M.D., for their helpful suggestions and their review of earlier versions of this paper.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, Harborview Medical Center, Box 359911, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses by whether they were interested in creating psychiatric advance directives

1. Lipton L: Psychiatric advance directives keep patients in control of care. Psychiatric News 35:12, 26, 2000Google Scholar

2. Srebnik D, LaFond J: Advance directives for mental health services: current perspectives and future directions. Psychiatric Services 50:919–925, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Swanson J, Tepper M, Backlar P, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: an alternative to coercive treatment? Psychiatry 63:160–172, 2000Google Scholar

4. Gallagher E: Advance directives for psychiatric care: a theoretical and practical overview for legal professionals. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:746–787, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mester R, Toren P, Gonen N, et al: Anticipatory consent for psychiatric treatment: a potential solution for an ethical problem. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 5:160–167, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Rogers J, Centifanti J: Beyond "self-paternalism": response to Rosenson and Kasten. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:9–14, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Sherman P: Advance directives for involuntary psychiatric care, in Proceedings of the 1994 National Symposium on Involuntary Interventions: The Call for a National Legal and Medical Response. Houston, University of Texas, 1995Google Scholar

8. Hoge S: The Patient Self-Determination Act and psychiatric care. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 22:577–586, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

9. Fleischner R: Advance directives for mental health care: an analysis of state statutes. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:788–804, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Srebnik D, Brodoff L: Implementation of mental health advance directives: service provider issues and answers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

11. Priaulx E: Report on Current Advance Directive Laws. Washington, DC, Advocacy Training and Technical Assistance Center of the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Systems, prepared for the Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

12. Psychiatric Advance Directives. Position paper. Alexandria, Va, National Mental Health Association, March 2, 2002. Available at www.nmha.org/position/advancedirectives.cfmGoogle Scholar

13. Honberg R: Advance directives. Journal of NAMI California 11(3):68–70. Also available at www.nami.org/legal/advanced.htmlGoogle Scholar

14. Williams X: Advance directives are what you make them. National Empowerment Center Newsletter, 1999. Available at www.power2u.org/selfhep/directives.htmlGoogle Scholar

15. Kupersanin E: Committing a loved one can be the best medicine. Psychiatric News 36 (17):13–14, 2001Google Scholar

16. Backlar P, McFarland B, Swanson J, et al: Consumer, provider, and informal caregiver opinions on psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:427–441, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Geller J: The use of advance directives by persons with serious mental illness for psychiatric treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly 71:1–13, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Anthony W: The philosophy and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation. Boston, Mass, Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1991Google Scholar

19. Miller R: Advance directives for psychiatric treatment: a view from the trenches. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:728–745, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Srebnik D, Livingston J, Gordon L, et al: Housing choice and community success for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 31:139–152, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Winick B: Advance directive instruments for those with mental illness. University of Miami Law Review 51:57–95, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

22. Backlar P, McFarland B: A survey on use of advance directives for mental health treatment in Oregon. Psychiatric Services 47:1387–1389, 1996Link, Google Scholar

23. Rosenson M, Kasten A: Another view of autonomy: arranging for consent in advance. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:1–7, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Swanson J, Swartz M, Hannon M, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: considerations and questions for research. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, in pressGoogle Scholar

25. Sutherby K, Szmuker G, Halpers A, et al: A study of 'crisis cards' in a community psychiatric service. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:56–61, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Torrey EF, Kaplan R: A national survey of the use of outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 46:778–784, 1995Link, Google Scholar

27. Schoenwald S, Hoagwood K: Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatric Services 52:1190–1197, 2001Google Scholar

28. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Srebnik D, Uehara E, Smukler M, et al: The Problem Severity Summary: psychometric properties of a multidimensional assessment instrument for adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:1010–1017, 2002Link, Google Scholar