Psychometric Properties and Utility of the Problem Severity Summary for Adults With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors studied the psychometric properties and utility of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS), a 13-item instrument that assesses symptom severity and functioning among adults with severe and persistent mental illness. METHODS: Case managers rated the PSS among more than 1,000 adults with severe and persistent mental illness who were receiving services at either mainstream community mental health centers or specialty community mental health centers (serving various minority groups) in one county in Washington State. A subsample of clients was used to assess the concurrent validity of the PSS with the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. RESULTS: Interrater reliability was adequate for ten of the 13 PSS items. Four meaningful factors were derived, each with adequate internal consistency: community functioning, negative social behavior, affective distress, and psychotic disturbance. The PSS demonstrated adequate concurrent and predictive validity. Sensitivity of the PSS factors to change showed that scores on three of the four scales changed significantly over one year. Discriminant validity indicated that the PSS is generally unbiased in terms of demographic characteristics. CONCLUSIONS: The PSS is a brief, easily administered instrument that shows psychometric promise for use in clinical contexts, such as treatment planning, concurrent review of care, and guidance for level-of-care decisions, as well as for quality management purposes.

Public mental health services recently have been under increased demands to demonstrate effectiveness and accountability. One way to demonstrate effectiveness is through assessment and monitoring of changes in consumers' symptoms and functioning. Such an approach has clinical value as a guide to treatment planning, level-of-care decisions, and review of treatment outcomes. At an aggregate level, assessment information can be used to risk-adjust comparisons of caseload or agency performance (1) and to develop standards of care or clinical pathways for case mix groups (2).

These goals can be met only by using multidimensional instruments that assess enough domains relevant to adults who have severe and persistent mental illness to guide clinical practice and provide useful information for performance monitoring (3). Unidimensional instruments, such as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (4), are considered to have insufficient sensitivity for monitoring outcomes, because they aggregate clinical domains that may not consistently covary, such as symptoms and functioning (5,6). In addition to multidimensionality, instruments must have adequate psychometric properties and be brief, practical, and able to be completed easily by clinicians who do not have advanced degrees but who are often the primary caregivers for adults with severe and persistent mental illness.

Although a variety of assessment instruments have been developed, few meet these requirements. A complete review of extant instruments is beyond the scope of this article. However, some of the limitations of these instruments have been described (7,8,9). For example, some instruments inadequately or incompletely assess relevant functioning domains, such as the 30-item Nurses Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE-30) (10), the Social Behavior Schedule (11), the Rehabilitation Evaluation of Hall and Baker (REHAB) (12), the Levels of Function Scale (13), and the Role Functioning Scale (14,15).

Other instruments are impractical because they require ratings to be completed by a highly trained interviewer, such as the Social Adjustment Scale-II (16) and the Psychiatric Evaluation Form (17), or a significant other, such as the Social Behavior Assessment Schedule (18), the Personal Adjustment and Role Skills Scale (19), and the Self-Assessment Guide (20). Still others are too long to be completed on a routine basis, such as the Community Adaptation Schedule (21), the Katz Adjustment Scale (22), and the Social Stress and Functioning Inventory for Psychotic Disorders (23). Some more recently developed instruments surmount these problems with their balance of comprehensive coverage of relevant domains in relatively brief scales—for example, the 32-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (24), the Functional Assessment Rating Scale (25), the Colorado Client Assessment Record (26), and the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (27).

The Problem Severity Summary (PSS) is similar to these more recently developed instruments in its coverage of relevant clinical domains, and it also has a brief, easy-to-use format. The PSS includes 13 global domains that are rated on Likert severity scales. These domains are dangerous behavior, self-care, community living, negative social behavior, social withdrawal, sociolegal, response to stress, sustained attention, symptoms of depression, anxiety symptoms, psychotic symptoms and thought disorder, physical, and health status. The PSS has been used for more than seven years in two large county public mental health systems in Washington State, which together serve about a third of the state's public-sector adult psychiatric population. The PSS was designed to be useful as a clinical tool for treatment planning and progress review. For example, agencies have developed treatment plans in which clinicians endorse PSS domains that are a current focus and describe specific planned interventions related to each domain.

The PSS has also been used as the basis of a countywide level-of-care placement system that drives case-rated payment (2). In addition, it is used to track outcomes for performance monitoring at the individual case level and at the agency and system levels. Recently, fiscal incentives for agencies have been tied to improved aggregate PSS scores. Overall, the PSS has been used for a wide range of clinical and quality management purposes in public mental health. The purpose of this article is to describe the psychometric properties of the PSS and its utility for clinical practice and quality management in community mental health services.

Methods

Participants

Interrater reliability analyses were based on PSS ratings made by two groups of case managers in a large county public mental health system in Washington State. The first group rated a random sample of 60 adult consumers from five specialty community mental health centers serving African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and persons who identified themselves as gay or lesbian. The second group of case managers rated a random sample of 100 adult consumers from all other mainstream community mental health centers in the county. Each case manager chose another service provider who knew each consumer well and who separately completed a PSS for each consumer.

All consumers who were receiving services from one nonspecialty community mental health center in the same county during a three-month period (N=1,148) were assessed by their case managers to generate data for internal consistency, predictive validity, and most concurrent validity analyses. The demographic composition of the sample was 56.3 percent white and 51.6 percent male. The mean±SD age of the consumers was 51.5±16.4 years, and the mean GAF score was 46.5±15.8. The consumers' diagnoses were schizophrenia spectrum disorders (39.4 percent), major depression (30.8 percent), bipolar disorders (25.1 percent), and other diagnoses (4.7 percent). Case managers at this community mental health center routinely completed PSS ratings for consumers on a quarterly basis for treatment planning purposes. A subsample of 162 consumers at the same center was used for analyses of the PSS's concurrent validity with the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS) (28).

Instruments and data collection

Problem Severity Summary. The selection of PSS domains was guided by input from panels of clinicians, advocates, and consumers. The PSS comprises 13 single-item domains: community living skills; self-care; physical disabilities; health status, such as chronic illnesses; dangerousness to self or others; negative social behavior, such as conflicts with others, interfering, or offensive behavior; sociolegal issues, such as law-breaking without dangerousness; anxiety symptoms; depressive symptoms; response to stress, such as coping skills; psychotic symptoms; social withdrawal; and sustained attention, a key aspect of task performance.

Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 5 with the following general scale anchors, each rated relative to other persons of the same sex, age, and subculture: 0, above average; 1, average; 2, slight impairment; 3, marked impairment; 4, severe impairment; and 5, extreme impairment. All ratings are based on the lowest level of functioning observed over the preceding 90 days. These general anchors as well as anchors for each rating for each item are further described in a training manual. The PSS data presented below were collected before the introduction of fiscal incentives to eliminate the possibility that incentives could inflate PSS scores.

Concurrent and predictive validity instruments. The PSAS (28) was used as one measure of the concurrent validity of the PSS. The PSAS is a 22-item instrument of symptom severity, developed as a revision to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (29). The PSAS version we used did not include four items—somatic concern, unusual ideas, social withdrawal, and mannerisms—and combined two items that refer to hallucinations into one item. Other measures of concurrent validity were drawn from the community mental health center's management information system, in which data are updated for change in status. For concurrent validity, the most recent status of the following data elements was used: GAF score, diagnosis, employment, homelessness, independent housing, physical disability, cognitive disability, and jail and psychiatric hospital episodes in the preceding year (dichotomized as 0, no, or 1 or more, yes).

For predictive validity, data were collected one year after the index PSS score for the following variables: GAF score, employment, homelessness, independent housing, and jail and psychiatric hospital episodes during the year (also dichotomized). Data on gender, age, and ethnicity obtained from the management information system were used to assess discriminant validity.

Statistical analyses

The analyses began with the calculation of intraclass correlations for each PSS item to determine interrater reliability. Principal-components analysis was then conducted to examine the factor structure of the PSS. Alpha coefficients of internal consistency for each derived factor were then calculated. The concurrent validity of PSS factors was assessed with correlations to items on the PSAS and the GAF, with F tests for diagnosis, and with t tests for employment, homelessness, independent housing, jail and psychiatric hospital episodes in the previous year, and having a physical or cognitive disability. Predictive validity of the factors over one year was then tested with correlations to the GAF and with t tests for employment, homelessness, independent housing, and jail and psychiatric hospital episodes. Paired t tests and effect size were used to assess sensitivity to change. Discriminant validity of the PSS factors was analyzed with correlations to age and with t tests for gender and ethnicity (Caucasian or non-Caucasian) to determine whether scores were biased toward any of these demographic characteristics. Because of the large number of statistical analyses, a probability level of p<.001 was used to control for type I error.

Results

Reliability

Interrater reliability. A priori, we interpreted the intraclass correlations in the following manner: .60 or greater, strong; .40 to .59, moderate; and less than .40, weak. When these criteria were used, interrater reliability was generally moderate for the mainstream community mental health centers and moderate to strong for the specialty agencies. Three items demonstrated weak interrater reliability for mainstream community mental health centers: anxiety, social withdrawal, and sustained attention. It is possible that these items had weak reliability because they referred to less apparent internal psychological issues.

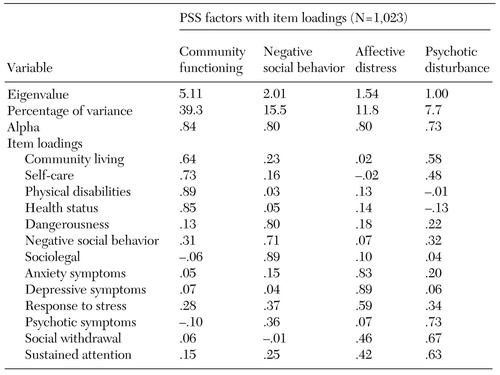

Factors and internal consistency.Table 1 shows the factor structure of the PSS and internal consistency for each factor. Principal-components analysis was conducted with varimax rotation to yield four factors that together accounted for 74 percent of scale variance. Each factor demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with alpha coefficients between .73 and .84. The community functioning factor included community living skills, self-care, physical impairment, and health status. The negative social behavior factor included dangerousness to self and others, negative social behavior, and sociolegal behavior. The affective distress factor included anxiety and depressive symptoms as well as response to stress. The psychotic disturbance factor included psychotic symptoms, social withdrawal, and sustained attention.

Validity

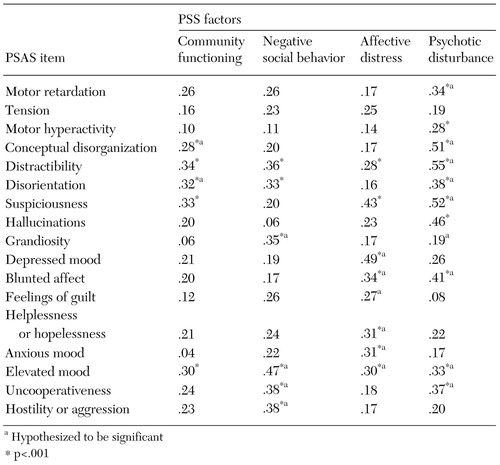

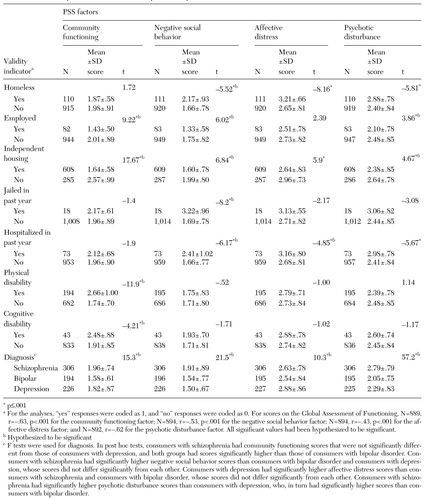

Concurrent validity. The results of concurrent validity analysis of the PSS factors are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The PSS community functioning factor was predictably correlated with few PSAS items because PSAS items assess symptoms, whereas the PSS community functioning factor assesses functional skills and physical or health care needs. The PSAS conceptual disorganization and disorientation items were correlated with this factor, probably because of their impact on basic skills and their relationship to dementia, a prominent health status issue. Suspiciousness and elevated mood were also correlated with this factor. As predicted, worse (higher) scores on this factor were related to lower GAF scores, having cognitive or physical disabilities, unemployment, and nonindependent housing. Community functioning scores of clients with schizophrenia were similar to those of clients with depression, and both groups had higher scores than clients with bipolar disorder.

The PSS negative social behavior factor was predictably correlated with the PSAS items grandiosity, elevated mood, hostility, and uncooperativeness. Interestingly, the PSAS items distractibility and disorientation were also moderately correlated, possibly as a result of the extreme agitation that would occur if an individual also demonstrated highly negative or dangerous behavior. As predicted, higher scores on this factor were related to lower GAF scores, jail and hospital episodes, unemployment, nonindependent housing, and homelessness. Clients with schizophrenia had worse negative social behavior scores than those with other diagnoses.

The PSS affective distress factor was predictably correlated with the PSAS items depressed mood, blunted affect, helplessness or hopelessness, anxious mood, and elevated mood. However, the affective distress factor was not significantly correlated with the PSAS item feelings of guilt. Surprisingly, suspiciousness and distractibility were significantly related. As predicted, higher scores on this factor were related to lower GAF scores and psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year. Higher affective distress was also related to nonindependent housing and to homelessness, although we had not predicted these relationships. Clients with depression, but not those with bipolar disorder, had worse affective distress scores than those with schizophrenia.

The PSS psychotic disturbance factor was predictably correlated with the PSAS items positive psychotic symptoms (conceptual disorganization, distractibility, disorientation, suspiciousness, hallucinations, and elevated mood) and negative symptoms (motor retardation, blunted affect, and uncooperativeness). However, this factor was not correlated with grandiosity. As predicted, higher scores on this factor were related to lower GAF scores, unemployment, non independent housing, psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year, and homelessness. Clients with schizophrenia had worse psychotic disturbance scores than those with other diagnoses.

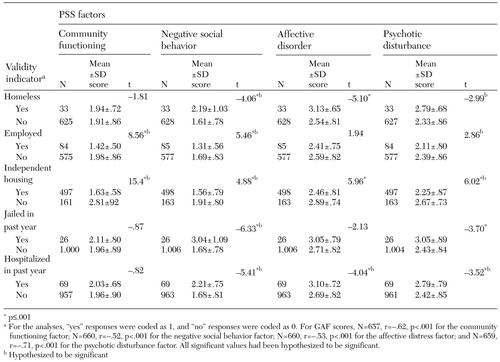

Predictive validity. The results of predictive validity analysis of PSS factors over one year are summarized in Table 4. The relationships of factors to validity variables largely followed the patterns observed for concurrent validity except that the psychotic disturbance factor was not significantly related to homelessness or employment but was significantly related to jail episodes.

Sensitivity to change. To assess the sensitivity of PSS factors to change, paired t statistics and effect sizes were calculated to compare ratings at baseline with those at 12 months. Three of the four PSS factor scores changed significantly over the course of a year. The effect sizes were moderate for psychotic disturbance (.46) and very small for affective distress (.04), negative social behavior (.07), and community functioning (.13)

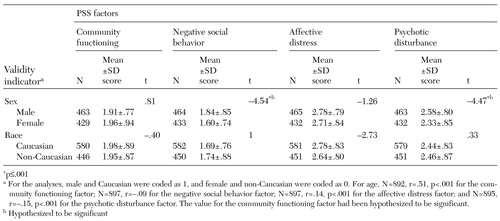

Discriminant validity. The results of the discriminant validity analysis of PSS factors are summarized in Table 5. Although most relationships were not significant, which suggests that the PSS is not biased with respect to demographic characteristics, a few notable significant relationships emerged. As predicted, age was associated with the community functioning factor, because this factor includes physical disabilities, health status, and self-care needs. Age was also significantly—but very weakly—correlated with the affective distress and psychotic disturbance factors. As predicted, male gender was associated with higher (worse) scores on the negative social behavior factor and psychotic disturbance factor, given the higher prevalence of corrections involvement among males and that schizophrenia symptoms are considered to be more severe and prominent in males (personal communication, Ries R, 2000).

Discussion and conclusions

Our results showed that interrater reliability was adequate for ten of the 13 items of the PSS, a brief multidimensional assessment of functioning and symptoms for use with adults who have serious and persistent mental illness. Four meaningful factors were derived, each with adequate internal consistency: community functioning, negative social behavior, affective distress, and psychotic disturbance. Concurrent and predictive validity analyses demonstrated logical relationships between PSS factors and validity variables. Sensitivity of the PSS factors to change showed that three of the four scale scores changed significantly over the course of one year. Discriminant validity analyses showed the PSS to be generally unbiased with respect to demographic characteristics. These findings suggest that the PSS has psychometric promise.

Limitations of the PSS

Our results are based on a limited sample from one county in Washington State. The study needs to be replicated with a larger sample and in other locations to strengthen the evidence for the generalizability of the PSS psychometric data and its utility in practice. Also, the PSS does not assess some domains that are relevant for adults with serious and persistent mental illness, such as substance use, medication adherence, and cognitive impairment. Earlier versions of the PSS included items for these domains; however, they proved to be highly unreliable and were excluded from subsequent versions. It is likely that substance use and cognitive domains require multiple items if they are to be assessed accurately. Thus existing rating scales for these domains could be used to supplement the PSS for these domains. Medication adherence might be more usefully assessed with an estimated percentage of time the consumer takes medications as prescribed.

Clinical utility of the PSS

The PSS was developed on the basis of domains that are of interest to clinicians and to be easily completed by clinicians who do not necessarily have advanced degrees. The instrument's brevity and sensitivity to change make is feasible for repeated administration to assess outcomes. In Washington State the PSS has been used for clinical treatment planning and progress monitoring. Specifically, PSS domains are expected to be reviewed collaboratively by consumers and their case managers to develop treatment plans. Concurrent review at the individual case level requires a reassessment of the PSS and notation of progress made on goals from the previous plan period. Change in PSS scores are thus one indicator of outcomes at the individual level.

A system for making mental health level-of-care decisions based on the PSS has also been developed (2). An algorithm based on combinations of PSS severity ratings guides placement into eight service levels ranging from brief treatment to inpatient care. Use of such tools can facilitate appropriate decisions about service intensity.

Utility of the PSS for quality management

The PSS may also be used for a variety of quality management purposes. For example, the same level-of-care algorithm described above, in the aggregate, has been used for planning and determining an equitable allocation of services on the basis of clinical need across an entire mental health system (2). Differential payment is tied to each level. This method may also be used to shape the development of standards of care or clinical pathways for case mix groups.

Outcomes can be monitored with the PSS at the program, agency, and system levels. Changes in PSS scores may be the outcome of interest, or the PSS may be used to risk-adjust the severity of caseloads to make equitable comparisons of other outcomes. Fiscal incentives may also be tied to improvement in aggregate PSS scores. It should be noted that a tool such as the PSS is only one component of a broader outcome-monitoring and quality management system that also includes sampling strategies, data collection methods, data analysis, and feedback to users (30).

Caution is necessary in using one instrument for both clinical and quality management purposes, because the accuracy of ratings may be eroded if the goal of clinical treatment planning and progress review is not clearly paramount. For example, tying improvements in PSS ratings to fiscal incentives may cause biased ratings, particularly if clinicians are aware of the incentives. Furthermore, implementing incentives for improved outcomes alone may lead to "creaming," or shifting access to services toward individuals who more easily attain desired outcomes. Thus a challenge is to retain as a primary emphasis clinical treatment planning and progress review rather than fiscal incentives.

In sum, the PSS can be a useful tool for a variety of clinical and quality management functions. Clarity and prioritization of these functions are key to the usefulness of information derived from the PSS for informing service and performance improvements.

Dr. Srebnik, Dr. Russo, Dr. Comtois, and Dr. Snowden are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Uehara is with the School of Social Work at the University of Washington in Seattle. Mr. Smukler is a behavioral outcomes management consultant in Seattle. Send correspondence to Dr. Srebnik, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Box 359911, 325 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Factor structure and internal consistency of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS)

|

Table 2. Concurrent validity of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS) with items from the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS) (N=157)

|

Table 3. Concurrent validity of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS) (N=1,148)

|

Table 4. Concurrent validity of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS) (N=1,148)

|

Table 5. Discriminant validity of the Problem Severity Summary (PSS) (N=1,148)

1. Hendryx M, Dyck D, Srebnik D: Risk-adjusted outcome models for public mental health outpatient programs. Health Services Research 34:171-195, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

2. Srebnik D, Uehara E, Smukler M: Field test of a tool for level-of-care decisions in community mental health. Psychiatric Services 49:91-97, 1998Link, Google Scholar

3. Brekke J: An examination of the relationships among three outcome scales in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:162-167, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Dickerson F, Boronow J, Ringel N, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 21:75-83, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goldman H, Skodol A, Lave T: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1148-1156, 1992Link, Google Scholar

7. Weissman M, Sholomsckas D, John K: The assessment of social adjustment. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:1250-1258, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dickerson F: Assessing clinical outcomes: the community functioning of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:897-902, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Wallace C: Functional assessment in rehabilitation. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:604-630, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Honigfeld G, Roderic D, Klett J: NOSIE-30: a treatment sensitive ward behavior scale. Psychological Reports 19:180-182, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wykes T, Sturt E: The measurement of social behavior in psychiatric patients: an assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry 148:1-11, 1978Google Scholar

12. Baker R, Hall J: Rehabilitation Evaluation of Hall and Baker (REHAB). Aberdeen, Scotland, Vine, 1983Google Scholar

13. Strauss J, Carpenter W: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I. characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:789-746, 1972Google Scholar

14. Goodman C, Sewell D, Cooley E: Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363-379, 1993Google Scholar

15. McPheeters H: Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two southern states. Community Mental Health Journal 20:44-55, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schooler N, Hogarty G, Weissman M: Social Adjustment Scale II (SAS-II), in Resource Material for Community Mental Health Program Evaluators. Edited by Hargreaves W, Attkisson C, Sorenson J. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1979, pub ADM 79-328Google Scholar

17. Endicott J, Spitzer R: What! Another rating scale? The Psychiatric Evaluation Form. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 154:88-104, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Platt S, Weyman A, Hirsch S: The Social Behavior Assessment Schedule (SBAS): rationale, contents, scoring, and reliability of a new interview schedule. Social Psychiatry 15:43-55, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Ellsworth R, Foster L, Childers B, et al: Hospital and community adjustment as perceived by psychiatric patients, their families, and staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 32:1-41, 1968Google Scholar

20. Willer B, Biggin P: Self-Assessment Guide: Rationale, Development, and Evaluation. Toronto, Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital, 1974Google Scholar

21. Burnes A, Roen S: Social roles and adaptation to the community. Community Mental Health Journal 3:153-158, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Katz M, Lyerly S: Methods for measuring adjustment and social behavior in the community: I. rationale, description, discriminative validity, and scale development. Psychological Reports 13:502-535, 1963Google Scholar

23. Serban G: Social Stress and Functioning Inventory for Psychotic Disorders (SSFIPD): measurement and prediction of schizophrenics' community adjustment. Comprehensive Psychiatry 19:337-347, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Eisen S, Dill D, Grob M: Reliability and validity of a brief patient-report instrument for psychiatric outcome and evaluation. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:242-247, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Ward J, Dow M: The Functional Assessment Rating Scale. Tampa, Fla, Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida, 1994Google Scholar

26. Ellis R, Wilson N, Foster M: Statewide treatment outcome assessment in Colorado: the Colorado client assessment record (CCAR). Community Mental Health Journal 20:72-89, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland B, et al: A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: I. reliability and validity. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363-379, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Bigelow L, Berthot B: The Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 25:168-178, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

29. Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Srebnik D, Hendryx M, Stevenson J, et al: Development of outcome indicators for monitoring quality in public mental health. Psychiatric Services 48:903-909, 1997Link, Google Scholar