Mental Health Services Received by Depressed Persons Who Visited General Practitioners and Family Doctors

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study estimated the rates of mental health service provision and of specialist referral in primary care in Canada and investigated factors associated with receiving mental health services and with referral to mental health specialists among persons who reported major depressive episodes. METHODS: Data from the 1998-1999 Canadian National Population Health Survey were used. The 608 respondents who reported having major depressive episodes in the 12 months preceding the survey and who reported contacting a general practitioner or family doctor during that time were included in the study. The rates of provision of mental health services by general practitioners and family doctors and of referral to mental health specialists were calculated. Demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics associated with receiving mental health services and with referral to specialists were investigated. RESULTS: Among the 608 respondents who had contacted general practitioners or family doctors for any reason, 153 had contacted them for emotional or mental problems. Of this subgroup of 153, 64.5 percent received mental health services either from these practitioners or by referral to specialists, and 26 percent were referred to mental health specialists. Depressed respondents who reported having talked to a general practitioner or family doctor about mental health problems, who reported impairment, and whose depressive symptoms had lasted eight or more weeks were more likely to have received mental health services. Respondents aged 12 to 24 years were more likely to be referred to mental health specialists. CONCLUSIONS: Impairment associated with depression and chronicity of depressive symptoms appear to be the primary determinants of the decisions made by general practitioners and family doctors about providing mental health services. Patients' willingness to consult with general practitioners or family doctors for mental health problems may also be a key factor, both for effective management of depression in primary care settings and for referral to mental health specialists.

Major depression is prevalent in primary care settings. Most patients with depression who seek treatment are initially seen by general practitioners or family doctors (1,2,3,4). Integration of mental health care into the primary care system has been widely advocated (5,6,7) for improving care. Previous studies suggest that clinicians in primary care settings often underdiagnose depression (8,9,10). In one study of patients whose psychiatric symptoms were recognized, 88 percent were not referred to a mental health specialist (11). The referral process from general practitioners to mental health specialists has been viewed as the "least permeable filter" separating specialists from the population (12). However, no existing criteria define the appropriate level of referral. It is important to investigate factors related to primary care physicians' provision of mental health services and to their patterns of referral to specialists. Such information is pivotal for determining optimal referral patterns, planning physical and mental health services, and effectively allocating human and financial resources (13,14).

Many factors may be associated with receiving mental health services and referral to a specialist, including doctor-patient relationship, societal stigma, and level of knowledge of mental disorders among primary care physicians (15,16). Previous studies have shown the importance of insurance coverage (17,18,19,20). In Canada, mental health services, including hospital and physician services, are covered under a single-payer, universal-access (publicly funded) system (21). However, the Canadian system may control costs by restricting access, thus decreasing service provision.

Several studies have investigated factors associated with mental health services provided by primary care physcians and with referrals they have made to mental health specialists. Men and persons who were younger than 45 years of age, were single, or had psychotic disorders have been found more likely to be referred (15,22). A recent study found that being referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist did not depend on patients' age or marital status but that persons in urban areas had a higher chance of being referred (23). Samples in these studies included respondents with various psychiatric symptoms; therefore, the findings may not be applicable to persons with major depression.

This study examined individuals who had reported major depressive episodes and who had contacted general practitioners and family doctors in the past 12 months. We estimated the rates of mental health service provision and of referral to a mental health specialist in primary care settings and compared the differences in demographic and other characteristics between individuals who had received and who had not received mental health services and between individuals who had received and who had not received a referral to a mental health specialist.

Methods

Data from the 1998-1999 National Population Health Survey (NPHS) (24) were used. The NPHS household component is a national health survey carried out by Statistics Canada. This component targets household residents in all Canadian provinces, excluding Indian reserves, military bases, the Yukon and Northwest Territories, and some remote areas in Quebec and Ontario, as well as residents of long-term institutions (25,26). The survey uses multistaged sampling procedures. In the 1998-1999 NPHS, 17,244 respondents were interviewed. Informed consent was obtained by Statistics Canada interviewers.

The NPHS data are in the public domain, with certain confidential data suppressed or removed. To access the confidential data, the master file data kept at Statistics Canada are used through remote-access data-analysis procedures. The results from the analyses go through rigorous security checks before they are released to researchers. Part of the study reported here used master file data; only persons who had had a major depressive episode and had contacted a general practitioner or family doctor in the past 12 months were included (N=608).

In the NPHS, major depressive episodes were measured by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form for Major Depression (CIDI-SFMD), derived from the full version of the CIDI and validated by Kessler and colleagues (27). A probability rating of .9 on the CIDI-SFMD represents the presence of five of eight different depressive symptoms in the same two-week period in the preceding 12 months. One must be either depressed mood or loss of interest, as consistent with DSM-IV criterion A for major depressive episode (28). To be consistent with DSM-IV, a major depressive episode was defined in the study reported here as a probability rating of .9 or higher on the CIDI-SFMD.

The NPHS respondents were asked, "In the past 12 months, how many times have you seen or talked on the telephone with a family doctor or general practitioner about your physical, emotional, or mental health?" An answer of "one or more times" was defined in the study reported here as indicating contact with a general practitioner or family doctor. Respondents in the NPHS were also asked if they had seen or talked to a health professional specifically about emotional or mental health problems in the preceding 12 months. "Health professional" in the NPHS included a general practitioner or family doctor, psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, social worker, or counselor. In the study reported here, the term "mental health specialist" was used instead and included psychiatrists and psychologists. Additionally, the NPHS respondents were asked, "In the past month, did you take antidepressants?" In the study reported here, taking antidepressants was included as part of the definition of "receiving mental health services."

Demographic and socioeconomic data included in our study were gender; age, classified as 12 to 24 years, 25 to 54 years, and 55 years or older; marital status; income adequacy, classified as low family income and middle or high family income; and urbanicity, referring to living in a rural or urban area. In the NPHS, income adequacy was determined by total family income and the number of individuals living in a household. Clinical variables in our study included having one or more long-term medical conditions, such as heart disease, hypertension, and asthma; impairment; and chronicity of depression. The NPHS adopted a question about impairment from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey (29): "How much do these experiences (depressive symptoms) usually interfere with your life or activities?" Responses were a lot, some, a little, and not at all. To be consistent with studies using the National Comorbidity Survey data (30,31), the answer "a lot" was defined in the study reported here as severe impairment, and other answers to this question were classified as mild or no impairment. The duration of depressive symptoms had two categories, using the median value for the respondents with major depressive episodes: two to seven weeks and eight weeks or longer. The NPHS question about duration had an upper limit of 52 weeks, and some depressive episodes last longer than this. However, a study using the NPHS data indicated that the duration of depressive episodes reflected in the NPHS was comparable with durations reported in other community-based studies (32).

We conducted three separate analyses. In the first analysis, the proportions of respondents who were seeing a psychiatrist, a psychologist, and either of them were calculated separately: first for respondents who had visited general practitioners and family doctors for any reason, and second for respondents who had seen general practitioners and family doctors about emotional or mental problems.

In the second analysis, respondents who had received and had not received mental health services were compared in demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Receiving mental health services was defined as having visited a psychiatrist or psychologist, having been treated with antidepressants by general practitioners and family doctors, or both. Because antidepressants can be prescribed only by physicians, respondents who were using antidepressants but had not visited a psychiatrist were assumed to have been treated with antidepressants by general practitioners and family doctors.

The analytic procedures used in the second analysis were repeated in the third. Respondents who had visited a psychiatrist or psychologist, termed referrals, were compared with respondents who had not visited a psychiatrist or psychologist, termed nonreferrals, in demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Only respondents who had visited general practitioners and family doctors for emotional or mental health problems were in the denominator of the referral rate estimates, thus excluding "bypassers."

The NPHS employed a complex multistage sampling design. To account for the sampling and design effects, sampling weights were used to calculate accurate estimates, and a bootstrap technique was used to generate accurate variance estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals. These analyses were conducted with bootstrap sampling weights provided by Statistics Canada (33). The proportions and the 95 percent confidence intervals in the first analysis of the study reported here were calculated with the master file data and Statistics Canada's bootstrap macros. The differences between proportions for our study were determined by z tests based on the bootstrap coefficients of variations (33). The second and third analyses in our study were conducted with STATA 6.0 (34). The Pearson chi square statistic, converted into an F statistic, was used to determine whether the proportions were significantly different. The association between a variable and receiving mental health services or referrals was determined in the form of an odds ratio. The 95 percent confidence interval (CI) associated with the odds ratio was calculated with the STATA bootstrap command "bs 'commands', 'exp_list'" (34).

Results

In the 1998-1999 NPHS, 668 respondents (weighted percent=4.5) reported having a major depressive episode in the preceding 12 months. Among these, 608 (90.4 percent) had visited a general practitioner or family doctor, but only 153 (22.1 percent) reported that the visits were specifically for mental problems. Among respondents who had contacted general practitioners and family doctors for any reason, 250 respondents (40.6 percent) reported having received mental health services, which included being treated with antidepressants by any physician or seeing a psychiatrist or psychologist. Of those who had contacted general practitioners or family doctors for mental problems, 93 (64.5 percent) reported having received mental health services.

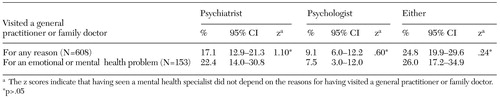

Table 1 shows the proportions who visited a psychiatrist or psychologist among those who reported contacts with general practitioners and family doctors for any reason and for reasons of mental or emotional health. Only 26 percent of the respondents who had contacted general practitioners and family doctors for reasons of mental or emotional health were referred to specialists. The z scores indicated that having seen a mental health specialist did not depend on the reasons for having visited a general practitioner or family doctor.

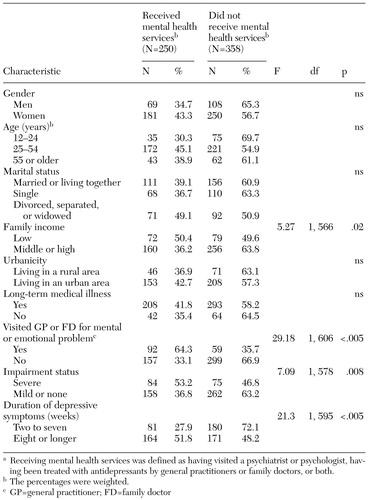

As shown in Table 2, respondents who were more likely to receive mental health services had visited general practitioners and family doctors for mental or emotional health, had severe impairment, had had depressive symptoms that had lasted eight weeks or longer, and had low family income. The association between income and receiving mental health services (odds ratio [OR]=1.79, CI=1.09 to 2.95) diminished when the effect of chronicity of depression was controlled for (OR=1.49, CI=.88 to 2.51). Receiving mental health services did not depend on gender, age, marital status, urbanicity, or having long-term medical illnesses.

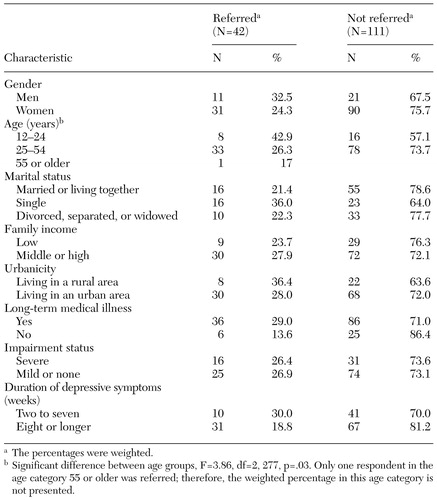

The demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics of respondents who were and were not referred to a mental health specialist are presented in Table 3. The results showed that respondents who were younger than 25 were more likely to be referred. Other factors were not associated with being referred.

Discussion

This study showed that, among respondents who reported major depressive episodes, 90.4 percent had contacted general practitioners or family doctors in the 12 months before the interview. This finding highlights the importance of primary care and the unique opportunities that primary care physicians have for detecting and managing individuals with major depressive episodes. However, only about 22 percent of the contacts with the general practitioners and family doctors were related to mental or emotional health problems, and only about 26 percent of individuals who made these contacts were referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies (23,35,36), indicating that a low referral rate is common in primary care settings. People with depression may not disclose their psychological symptoms to general practitioners and family doctors, which presents difficulties for detection of major depression by primary care physicians, a group that often has limited time and often focuses on acute physical illnesses (37). The proportion of the respondents who had contacted a general practitioner or family doctor for mental health problems in the NPHS (24) (22.1 percent) was higher than that reported in the Epidemiological Catchment Area study (38) (12.5 percent of those with affective disorders) and than that reported in the National Comorbidity Survey (39) (10.3 percent of those with major depression). The discrepancies may be partially due to the times at which the studies were conducted and to the different health care systems.

In the study reported here, 40 percent of patients who had consulted general practitioners and family doctors for any reason and 64.5 percent of those who had visited general practitioners and family doctors about mental or emotional health problems had received mental health services in the preceding year.

These estimates have limitations and should therefore be interpreted with caution. The NPHS was a general health survey and relied on self-reported information; therefore, the findings of this study were vulnerable to reporting bias. Mental health services in this study were defined as having visited a psychiatrist or psychologist, having been treated with antidepressants by general practitioners and family doctors, or both. Visits to general practitioners and family doctors were measured in the preceding 12 months, but antidepressant use referred to the month before the interview. For some respondents who reported a major depressive episode, primary care physicians might have decided to provide psychotherapy and counseling or education instead of prescribing antidepressants (21). Unfortunately, the NPHS did not collect information on psychotherapy and counseling or education. Therefore, the proportion in this study who had received mental health services may have been underestimated.

The study showed that receiving mental health services did not depend on respondents' demographic or socioeconomic characteristics but rather on whether they had approached general practitioners and family doctors for reasons related to mental or emotional health and also on the nature of their clinical presentation. Although income adequacy was associated with receiving mental health services in the crude analysis, the results indicated that this association was due to the confounding effect of chronicity of depression. Clinical presentation—as represented by the last three categories of characteristics in Table 2—appears to be an important determinant of decisions made by general practitioners and family doctors about providing services. These findings have intervention implications. If successful and effective patient education and antistigma programs can be established, patients with major depression may be more willing to disclose their depressive symptoms to general practitioners and family doctors. As a result, these patients may be more likely to receive appropriate mental health services.

Being referred to a mental health specialist was not related to impairment or to the duration of depressive symptoms. The proportion of respondents with depressive symptoms lasting eight weeks or longer was higher among the referrals than among the nonreferrals, but this difference was not statistically significant. There are several possible explanations. An important factor in the mental health referral process is the doctor-patient relationship (15). Other important factors include the availability of specialized mental health professionals in a specific region, patients' fear of being stigmatized, the organization of the primary care delivery system (16,37), poor communication between general practitioners and specialists, and cumbersome intake procedures in mental health services (40). From the NPHS perspective, some of the nonsignificant results could be due to the relatively small number of respondents who had visited general practitioners and family doctors for mental or emotional health problems (N= 153). Some individuals with chronic depression and severe impairment may have refused participation or may have been institutionalized at the time of interviews and may therefore not have been included in the NPHS. Consistent with previous studies, we found that younger people were more likely to be referred to mental health specialists (15,22).

A little more than 40 percent of patients who had contacted general practitioners and family doctors for any reason had received mental health services, indicating that these physicians appear to have recognized a large proportion of individuals with depression and provided mental health services by either prescribing antidepressants or referring patients to a specialist. There is evidence that primary care clinicians are sensitive to meaningful clinical cues such as family history and previous treatments in diagnosing depression (41). However, their diagnoses, as well as related referrals, may be affected by many factors, as discussed earlier. This particular finding was like those of previous studies in which a significant proportion of persons with mental disorders were recognized and treated by general practitioners and family doctors (12,15,42). However, there is room for improvement. Only a small proportion of those with a major depressive episode were referred to mental health professionals. Some with chronic depression and severe impairment were not referred, and a significant proportion did not receive any mental health services.

Conclusions

To improve the effectiveness of depression management in primary care settings, the education of persons who visit general practitioners and family doctors and a public campaign against stigmatizing depression may be necessary. Such strategies may increase patients' awareness of depressive symptoms and the disclosure of these symptoms to primary care clinicians, leading to more effective depression management in primary care settings and optimal referrals to mental health specialists, as evidenced by the results of this study. The NPHS was a general health survey and relied on self-reported information. Thus, the findings of this study were vulnerable to reporting bias. Well-designed studies using large samples are needed to further delineate the extent to which individuals with major depressive episodes may be underserved and undertreated in primary care settings and also to further examine referral patterns. Such studies will provide valuable information for integrating mental health with primary care.

Dr. Wang is assistant professor and Dr. Patten is associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and community health sciences of the faculty of medicine at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Dr. Langille is associate professor in the department of community health and epidemiology of the faculty of medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Send correspondence to Dr. Wang at Department of Psychiatry, Peter Lougheed Centre, 3500 26th Avenue N.E., Calgary, Alberta, Canada T1Y 6J4 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Weighted proportions of individuals with major depressive episodes who visited a psychiatrist or a psychologist, by the reasons for visiting a general practitioner or family doctor

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 608 survey respondents who reported major depressive episodes, by whether or not they received mental health servicesa

a Receiving mental health services was defined as having visited a psychiatrist or psychologist, having been treated with antidepressants by general practitioners or family doctors, or both.

|

Table 3. Characteristics of survey respondents who visited general practitioners and family doctors for mental health problems, by whether or not they were referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist

1. Simon GE, Von Korff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:850–856, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Norquist GS, Regier DA: The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders and the de facto mental health care system. Annual Review of Medicine 47:473–479, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277:333–340, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al: Depressive symptoms and the costs of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older: a 4-year prospective study. JAMA 277:1618–1623, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. World Health Organization: Mental health care in developing countries: report of a WHO study group. Technical Report Series 698. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1984Google Scholar

6. Klinkman MS, Okkes I: Mental health problems in primary care: a research agenda. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 28:361–374, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jenkins R, Strathdee G: The integration of mental health care with primary care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 23:277–291, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Von Korff M, Shapiro S, Burke JD, et al: Anxiety and depression in a primary care clinic: comparison of Diagnostic Interview Schedule, General Health Questionnaire, and practitioner assessments. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:152–156, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Munoz RF, et al: Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Archives of Internal Medicine 150:1083–1088, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Coyne JC, Schwenk TL, Fechner-Bates S: Nondetection of depression by primary care physicians reconsidered. General Hospital Psychiatry 17:3–12, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Huxley P: Mental illness in the community: the Goldberg-Huxley model of the pathway to psychiatric care. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 50:47–53, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Goldberg D, Huxley P: Mental illness in the community: the pathway to psychiatric care. London, Tavistock, 1980Google Scholar

13. Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA: The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:685–693, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Burns BJ, et al: Specialist/generalist division of responsibility for patients with mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:219–224, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Verhaak PF: Analysis of referrals of mental health problems by general practitioners. British Journal of General Practice 43:203–208, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pincus HA, Pechura CM, Elinson L, et al: Depression in primary care: linking clinical and systems strategies. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:311–318, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Expenditures for the treatment of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:883–888, 1998Link, Google Scholar

18. Rost K, Fortney J, Zhang M, et al: Treatment of depression in rural Arkansas: policy implications for improving care. Journal of Rural Health 15:308–315, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, et al: Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:189–195, 2001Link, Google Scholar

20. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Goering P, Wasylenki D, Durbin J: Canada's mental health system. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 23:345–359, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, et al: The relationship between demographic factors and attitudes toward mental health services. Journal of Community Psychology 15:275–284, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Sorgaard KW, Sandanger I, Sorensen T, et al: Mental disorders and referrals to mental health specialists by general practitioners. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:128–135, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Statistics Canada: NPHS cycle 3 (1998, 1999). Public use microdata files. Ottawa, Minister of Industry, 1999Google Scholar

25. Statistics Canada: National Population Health Survey Overview, 1994/95. Catalogue no 82–567. Ottawa, Minister of Industry, 1996Google Scholar

26. Beaudet MP: Depression. Health Reports 7:11–24, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

28. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

29. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Mojtabai R: Impairment in major depression: implications for diagnosis. Comprehensive Psychiatry 42:206–212, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al: Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys' estimates. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:115–123, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Patten SB: The duration of major depressive episodes in the Canadian general population. Chronic Diseases in Canada 22:6–11, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

33. Statistics Canada: National Population Health Survey, Household Component, 1996–1997, User's Guide for the Public Use Microdata Files. Catalogue no 82M0009XCB. Ottawa, Minister of Industry, 1998Google Scholar

34. Stata Statistical Software release 6.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corporation, 1999Google Scholar

35. Parikh SV, Lin E, Lesage AD: Mental health treatment in Ontario: selected comparisons between the primary care and specialty sectors. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:929–934, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Meadows G, Liaw T, Burgess P, et al: Australian general practice and the meeting of needs for mental health care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:595–603, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al: The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Archives of Family Medicine 9:150–154, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, et al: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:971–978, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115–123, 1999Link, Google Scholar

40. Craven MA, Cohen M, Campbell D, et al: Mental health practices of Ontario family physicians: a study using qualitative methodology. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:943–949, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Klinkman MS, Coyne JC, Gallo S, et al: False positives, false negatives, and the validity of the diagnosis of major depression in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 7:451–461, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Orleans CT, George LK, Houpt JL, et al: How primary care physicians treat psychiatric disorders: a national survey of family practitioners. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:52–57, 1985Link, Google Scholar