Patterns and Predictors of Service Use and Unmet Needs Among Aging Families of Adults With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined patterns and predictors of use of and unmet need for support services among aging families of adults with severe mental illness by using an expanded version of the Andersen Behavioral Model. METHODS: Mailed surveys were completed by 157 mothers from 41 states who lived with and provided care to adult offspring with serious mental disorders, primarily schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. The mean age of the mothers was 67 years (range, 50 to 88 years). RESULTS: Although unique patterns were observed among individual services, overall service use was low despite high perceived need for services. The greatest unmet needs were for social or recreational programming, training in behavior management, and information on planning for the future. Regression analyses based on the expanded Andersen model revealed that greater service use occurred when offspring spent their days away from home, mothers received higher levels of informal support, and offspring were in poorer physical health. Greater unmet needs for services were reported when mothers experienced higher burden, perceived more age-related changes in themselves, and had offspring who typically spent their days at home. CONCLUSIONS: The needs and resources of the entire family, including access to informal social support, should be considered in attempts to identify predictors of the use of and need for services among persons with chronic and severe mental illness. The findings of this study also point to the need for family education in how to locate community services as well as for better and more sensitive community services intended for the entire aging family.

More than a third of adults who have chronic and severe mental illness live with their families, primarily aging parents (1,2). Families contribute to the care of these individuals in important ways, such as by serving as primary caregivers or informal case managers, by helping to meet the needs of other families, or by advocating for improved systems of care (3). Families are so integral to the care system that the success of the movement toward caring for persons with severe mental illness in the community is said to hinge on the ability of families to provide a large portion of that care (4). Thus researchers and practitioners must address the needs and concerns of the entire family.

Although individual family members have similar needs for information, skills, and support, unique experiences and concerns are associated with such family subsystems as parents, spouses, or siblings (3). Despite growing interest in aging parents as caregivers, scant attention has been paid to older parents who care for adult offspring who have severe mental illness and provide the bulk of family care in the community (1).

Although support and care for a relative who has severe mental illness is demanding for parents of any age, the burden increases as the caregivers age and experience physical decline and other losses associated with old age (5). Even though the need for professionals to address the problems faced by aging parents has been widely documented (1,6,7), there are few data on the caregiving circumstances of these parents. The dearth of research on service use by aging parents and their offspring with mental illness is particularly unfortunate in light of advice that "a clear understanding of the patterns and correlates of service use is needed if service providers are to design, implement, and operate programs that reach target populations and make the most efficient use of limited resources" (8).

The purpose of the study reported here was to examine patterns and correlates of the use of family support services and perceived and unmet needs for such services in a national sample of older mothers caring at home for adult offspring with severe mental illness. Most previous studies of service use by adults with severe mental illness have been based on reports from either mental health professionals or consumers. However, the views of family members are also important, because families are often burdened with heavy emotional and financial responsibilities when their ill relatives cannot obtain needed services or support (2).

Although it has been claimed that services should be designed within a comprehensive system of care to meet the essential needs of people with severe mental illness and their families (3), past studies have focused more on the use of medical services than on social or rehabilitative services. Thus these studies have failed to recognize that adults with severe mental illness and their families "share with others who are chronically ill the need for a broad array of health and social services that address the disabling effects of their illness" (9).

This study expanded on the limited past research on use of services by adults with severe mental illness and their families in three key ways. First, it is acknowledged that the scope of services for these families as defined in this study is broad and includes such components as social or recreational services, case management, and family support programs that extend beyond the individual needs of the offspring with severe mental illness (10). For example, older families are likely to need assistance in planning for when the parents are no longer able to provide care (11,12). Second, whereas in most previous studies the views of older parents were not examined separately from those of other family members (2,4), this study focused on older mothers. Third, this study examined predictors of service use and unmet needs within the multivariate context of an expanded version the Andersen behavioral model of service use (13,14), whereas past research has mainly involved the use of descriptive univariate statistics in the absence of an explicit conceptual model.

The Andersen behavioral model

The Andersen behavioral model classifies individual predictors of service use into three categories: predisposing factors, such as sociodemographic characteristics and health-related beliefs, that shape attitudes toward service use; enabling factors, which refer to resources that promote or inhibit use; and need factors, which encompass the individual's illness or impairment that necessitate use (13,14). Although the model was originally developed to predict service use, it has also been used successfully to predict unmet needs for services (15).

Moreover, evidence shows that the Andersen model is even better suited to predicting use of community-based discretionary services than to its original purpose of predicting use of formal health services (16). Thus the behavior model was well suited for this study given its ability to identify predictors of the use of and unmet needs for family support services in the context of an established conceptual framework.

In applying the Andersen behavioral model to family caregiving, Bass and Noelker (17) expanded the model to encompass the predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of both the primary family caregiver and the recipient of care. Need factors associated with the primary caregiver emphasize the stress associated with caregiving, because caregivers who experience high levels of stress may influence the care recipient's use of community services in order to obtain relief from the burdens of caregiving. This expanded model further includes family-related enabling characteristics, thereby acknowledging the likely role of secondary caregivers in providing care.

Key assumptions of Bass and Noelker's (17) expanded model have been found to be relevant to aging parents of adults with chronic disabilities (18). One of these assumptions is that the primary caregiver may influence the care recipient's use of services both directly, such as a caregiver's contacting agencies to seek services for a care recipient, and indirectly, such as when caregivers influence care recipients' perceptions of illness or need. Aging caregivers can also affect service use if providers consider the caregiver's status—for example, inability to provide care—when assessing the needs of the recipient of care (17,18). Another relevant assumption is that secondary sources of informal help—for example, assistance provided by other family members—may influence the need for or use of formal services (17,18).

Patrick and Pruchno (19) applied the original behavioral model to data on service use and unmet need obtained from older mothers, but their study differed from the study reported here in several ways. First, a majority of respondents in their study were from Northeast Ohio, and only one third had their offspring living with them. Second, their analysis encompassed only ten services that were intended exclusively for the offspring and were biased toward formal health services. Third, need factors were restricted to those concerning the offspring. Finally, the potential impact of informal support was overlooked. Thus this study represents the first to examine the patterns and predictors of both use of and unmet need for a broad spectrum of family support services from the perspective of the expanded Andersen model.

Methods

Participants

Mothers aged 50 years or older who lived with adult offspring with severe mental illness were recruited between 1995 and 1997 to participate in a national survey on future planning through announcements in local, state, and national newsletters of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI). Participation was limited to mothers because mothers perform the bulk of caregiving (20).

The mothers were mailed a self-administered questionnaire covering a wide variety of circumstances surrounding family caregiving, accompanied by a letter regarding informed consent. A questionnaire, derived from earlier research on older mothers of adults with mental retardation (21), was adapted for mothers of adults with severe mental illness through pilot testing. The surveys were completed without assistance and returned in a self-addressed stamped envelope.

Measurement of predicting factors

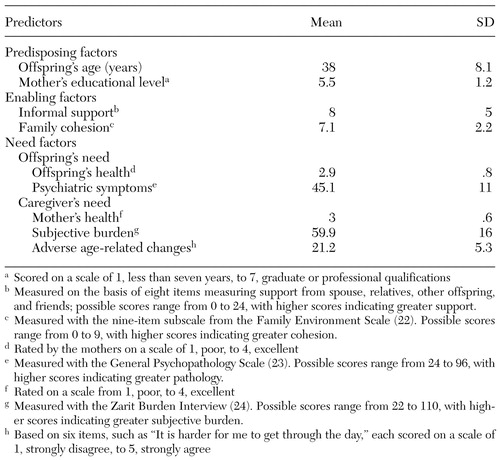

The survey encompassed information on predisposing factors (offspring's age, offspring's gender, mother's marital status, and mother's educational level), enabling factors (geographic location, informal support, family cohesion, and the manner in which the offspring spends a typical day), and need factors (22,23,24).

Consistent with the expanded behavioral model (17), need factors were bifurcated into those pertaining to the care recipient (offspring) and those pertaining to the primary caregiver (mother). Offspring's need factors were need for caregiving (for example, needs no help or requires much or total help with activities of daily living), offspring's health (rated by the mothers from poor to excellent), and psychiatric symptoms as measured by the General Psychopathology Scale (23). Severity of psychiatric symptoms was included as a need factor rather than as a diagnosis on the basis of evidence that service use is more effectively predicted by the level of impairment associated with symptoms or syndromes than by specific diagnoses (25). Caregivers' (mothers') need factors were mother's health (rated from poor to excellent), subjective burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Interview (24), and perceived adverse age-related changes.

Measurement of service-related constructs

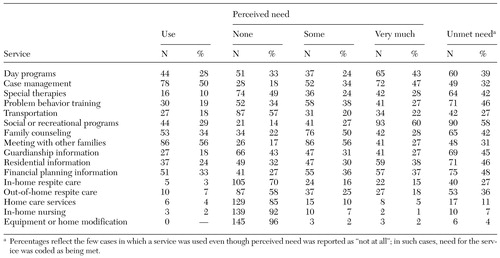

The mothers were asked to indicate whether each of 16 services had been used in the previous year and the extent to which each was currently needed on a scale from 1, not at all, to 3, very much. Heller and Factor (26) devised this list by reviewing research on family supports and family needs.

Service use scores were obtained by summing the number of services reported as being used. Unmet need was computed by summing the number of instances in which a service was reported as being needed but not reported as being used across the list of services. Two services that were used by fewer than 10 percent of respondents—home equipment and nursing—were not included in the calculation of the service use and unmet need scores.

Results

The recruitment yielded 196 mothers from 41 states, a response rate of more than 90 percent. Of the mothers who returned surveys, 157 met the criteria of living with their mentally ill offspring. The mean age of the respondents was 67 years (range, 50 to 88 years). Most of the mothers were non-Hispanic white (144 respondents, or 92 percent), married (96 respondents, or 61 percent), had at least a high school education (153 respondents, or 98 percent), and reported their health as good or excellent (123 respondents, or 79 percent). The offspring were primarily male (120 offspring, or 76 percent) and had an average age of 38 years (range, 20 to 58 years). Their diagnoses were schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (94 offspring, or 60 percent), multiple disorders (31 offspring, or 20 percent), bipolar disorder (25 offspring, or 16 percent), or other psychiatric illnesses (seven offspring, or 5 percent).

A majority of the offspring (114 offspring, or 73 percent) were reported by mothers to be in good or excellent physical health. One third were involved in activities outside the home—for example, day programs or supported or competitive employment—and half spent their typical day at home. Almost half of the mothers (74 respondents, or 47 percent) indicated that their offspring relied on them for help with everyday chores such as cooking and doing laundry, and 64 mothers (41 percent) reported that their offspring relied on them for help with chores in addition to help with structuring their day.

The sample was similar to samples used in previous NAMI studies in which the modal pattern in caregiving families consisted of an aging parental caregiver, typically a mother in her late 50s to 70s, who is taking care of a mentally ill son approaching middle age (27).

Mean values for various predisposing, enabling, and need factors are listed in Table 1. The frequencies of reported use, need, and unmet need for the 16 family support services are listed in Table 2. Service use was highest for meetings with other families, such as support groups, and case management, and these were the only services for which use exceeded unmet need. More than 40 percent of the families reported unmet needs for problem behavior training, family counseling, and information about planning for the future. Nearly 60 percent of the families reported an unmet need for social or recreational programs. Service use, perceived need, and unmet need were lowest for services oriented toward physical health problems, such as in-home nursing.

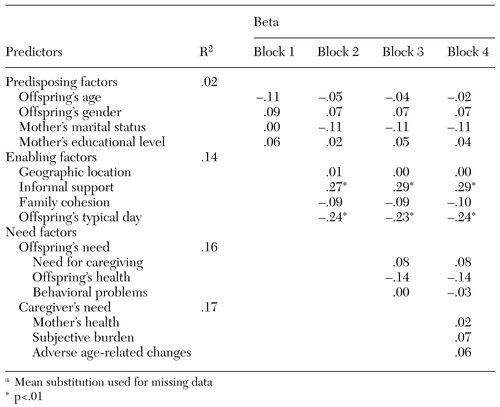

A four-step regression analysis was used to examine the individual predictors of overall service use as organized into blocks based on Bass and Noelker's model (17). The results are summarized in Table 3. This procedure yielded four equations, with each block entered according to the prioritized logic of the model. The procedure also permitted simultaneous control of each independent factor within the model.

The only two predictors of service use that were statistically significant in the final equation were availability of informal social support and offspring's spending the typical day away from home. However, poorer health of the offspring came close to being related to greater service use. In sum, enabling factors were more predictive of overall service use than were either predisposing or need factors.

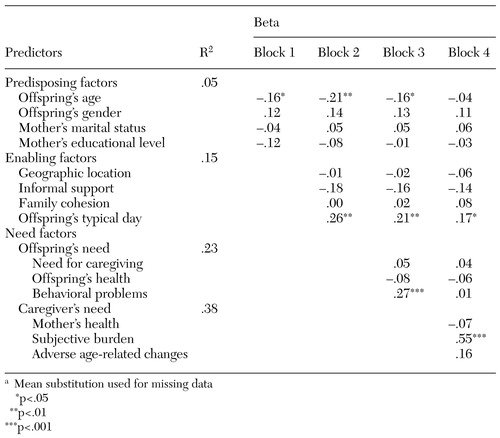

A similar four-step regression procedure was used to examine the predictors of overall unmet need. The results of this analysis, shown in Table 4, demonstrate the value of examining predictors within a multivariate context. Whereas higher levels of unmet need were initially associated with the offspring's gender and psychiatric symptoms, neither of these variables was predictive in later stages of the analysis. In the final regression equation, greater unmet need was significantly related to higher levels of subjective burden and offspring's spending a typical day at home. The mothers' perceptions of being adversely affected by age-related changes was close to being a significant predictor of unmet need in the final equation. Overall, need factors related to the maternal caregiver explained most of the variance.

Discussion

This study had several limitations. First, data on service use, need, and unmet need were based entirely on the mothers' self-reports, which may differ from evaluations by mental health professionals or by offspring with severe mental illness (28). Also, because the assessment of service need was limited to demand for services, alternative indexes of need, such as impairment or disability levels, were not considered. Moreover, a distinction was not made between families who received services that were not working well and those who received no help at all. Nevertheless, this study makes an important contribution by examining service needs among an expanding yet overlooked group of family caregivers.

The study was further limited in that the predictors of service use and unmet service need were focused narrowly on family and individual factors without consideration of potential societal determinants of service use, such as the family's racial or ethnic background or the availability, structure, and quality of relevant services (13,14). Nor was there any attempt to categorize the 16 family support services by type or purpose (13,14,19). Thus examining the role of societal factors and identifying the predictors of use and unmet need for specific family support services are key areas for future research.

Although the generalizability of the findings are limited by the self-selected nature of the sample, the generally low levels of service use and correspondingly high levels of unmet need we observed in this study are startling given that NAMI families are typically well-educated, financially secure, and more knowledgeable about services than are more disadvantaged families. Indeed, it has been claimed that if the service system fails to meet the needs of NAMI families, the experience of other families is probably even worse (29). Likely explanations for low service use include lack of services in the community, insufficient resources to enable use of services, poor fit between services and needs, and resistance to services among mental health consumers (9).

Consistent with the results of previous studies (2,19), the findings of this study showed that the greatest unmet need was for social or recreational programs. This result may be largely due to the fact that half of the offspring in the study sample spent their typical day at home. Similarly, Skinner and colleagues (2) found in their NAMI study that two of five adults with severe mental illness received no help with establishing and maintaining relationships, and three of five received no help with engaging in productive activities. Although professionals commonly regard day programs such as day centers as being suitable for structuring daytime activities and preventing social isolation, research suggests that many people with severe mental illness do not use these services because they view them as symbols of their own social disintegration (30).

This study also revealed substantial unmet need for services that provide assistance with future planning. This finding is consistent with the results of previous research showing that older parents of adults with diverse types of lifelong disabilities avoid planning for the future care of their offspring, even though future care is among the parents' greatest concerns (12,22). Hatfield and Lefly (5) found that older caregivers attributed this lack of planning more to themselves than to service providers, yet less than half turned to the service system for help with planning. Nonetheless, two-thirds of the family caregivers who did seek planning assistance from the system found such assistance to be helpful, which suggests that "providers could play constructive roles in helping more families with this issue" (5).

The use of the expanded Andersen model in this study revealed that enabling factors were the best predictors of service use, whereas caregiver and offspring need factors explained a majority of variance in unmet need. The relationships observed between how offspring spend a typical day and overall service use and unmet need are consistent with the view that participation in structured day activities is related to greater service use and reduction in unmet need (9). Yet aging mothers of adults with lifelong disabilities who do not use day programming are likely to need respite and other supports to maintain their offspring at home throughout the day (31). The results of this study illustrate how salient day programming is for aging families compared with other potential predictors that were not statistically significant in the multivariate context of the expanded Andersen model.

The positive association found between service use and the availability of informal support casts doubt on the speculation that social networks diminish service use by serving as substitutes for professional assistance. Instead, these findings corroborate the emerging belief that informal social networks stimulate service use by either transmitting positive attitudes toward services or by bringing about referrals to mental health services (32). Thus ensuring adequate size and quality of the informal social networks of aging families may improve access to needed services.

The finding that subjective burden was significantly related to having unmet needs parallels the results of previous studies of aging caregivers of adults with developmental disabilities, which found that unmet service needs were significantly related to caregiver stress and burden (18,27). Family caregivers of adults with severe mental illness have similarly been found to report that lack of community resources available to them and to their mentally ill relatives is a significant contributor to their burden (4,6).

However, the results of this study are also consistent with the belief that aging parents do not perceive a need for certain services unless they view their capacity as caregivers to be exceeded by caregiving demands (33). Regardless of the direction of causality, professionals should be aware of the established relationship between caregiver burden and unmet need in the design and implementation of services for adults with severe mental illness and their aging caregivers.

Conclusions

Older parents providing care to offspring with serious mental illness report low use of and high unmet need for family support services, especially for those intended to promote community integration of the offspring and to assist parents with future planning. The results of this study show that the needs and resources of the entire family, including the availability of informal social support, should be considered when identifying predictors of service use and need for this target population. The results also underscore the need for family education in locating community services and for better and more sensitive services intended for the entire family (4). Yet, within the context of this study, it must also be recognized that need is not necessarily equivalent to demand. Demand for services cannot always be followed by provision of those services or—if services are provided—by service use (34). In addition, demand, provision, and use can exist simultaneously in the absence of actual need for a given service (34).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the graduate research board of the University of Maryland at College Park. The author thanks Steven J. Kohn, Ph.D., and Julian Montero-Rodriquez, Ph.D., for their comments on an earlier draft.

Dr. Smith is professor and director of the Human Development Center, School of Family and Consumer Studies, 111 Nixson Hall, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, held November 22 to 26, 2002, in Boston.

|

Table 1. Mean±SD values of selected predictor variables in the expanded Andersen model of service use by aging caregivers and their offspring with chronic and severe mental illness

|

Table 2. Service use and perceived and unmet need for services in a sample of 196 aging caregivers of adult offspring with chronic and severe mental illness

|

Table 3. Results of regression of total service use on expanded Andersen model predictors of service use by aging caregivers and their offspring with chronic and severe mental illness (N=157)a

a Mean substitution used for missing data

|

Table 4. Results of regression of unmet need on expanded Andersen model predictors of service use by aging caregivers and their offspring with chronic and severe mental illness (N=157)a

a Mean substitution used for missing data

1. Lefly HP: Aging parents as caregivers of mentally ill adult children: an emerging social problem. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1063-1070, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Kasper JD: Family perspectives on service needs of people with serious and persistent mental illness. Innovations and Research 1(3):23-30, 1992Google Scholar

3. Marsh DT, Lefly HP, Evans-Rhodes D, et al: The family experience of mental illness: evidence for resilience. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20:3-12, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Francell CG, Conn VS, Gray DP: Families' perceptions of burden of care for chronic mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1296-1300, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Hatfield AB, Lefly HP: Helping elderly caregivers plan for the future care of a relative with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:103-107, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Cook JA, Cohler BJ, Pickett SA, et al: Life-course and severe mental illness: implications for caregiving within the family of later life. Family Relations 46:427-436, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Jennings J: Elderly parents as caregivers for their adult dependent children. Social Work 32:430-433, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

8. Krout JA: Knowledge and use of services: a critical review of the literature. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 17:153-167, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kasper JD, Steinwachs DM, Flynn LM: Patterns of health and social service use among people with severe and persistent mental illness, in Living in the Community With Disability: Service Needs, Use, and Systems. Edited by Allen S, Mor V. New York, Springer, 1998Google Scholar

10. Stockdill J: Definition of Psychosocial Rehabilitation: Technical Assistance Transmittal, no 1. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, Office of State and Community Liaison to State Mental Health Directors, 1985Google Scholar

11. Mengel MH, Marcus DB, Dunkle RE: "What will happen to my child when I'm gone?" A support and education group for aging parents as caregivers. Gerontologist 36:816-820, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Smith GC, Hatfield A, Miller D: Future planning by older mothers of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1162-1166, 2000Link, Google Scholar

13. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model in accessing medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1-10, 1995Google Scholar

14. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Quarterly 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Calsyn RJ, Winter MA: Predicting four types of service needs in older adults. Evaluation and Program Planning 24:157-166, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Mitchell J, Krout JA: Discretion and service use among older adults: the behavioral model revisited. Gerontologist 38:159-168, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bass DM, Noelker LS: The influence of family caregivers on elders' use of in-home services: an expanded conceptual framework. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 28:184-196, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Smith GC: Aging families of adults with mental retardation: patterns and correlates of service use, need, and knowledge. American Journal on Mental Retardation 102:13-26, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Patrick JH, Pruchno RA: Mothers' perceptions of service use and unmet service needs for their adult offspring with chronic mental illness. Psychiatric Annals 26:757-765, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Hoyert DL, Seltzer MM: Factors related to the well-being and life activities of family caregivers. Family Relations 41:74-81, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Smith GC, Tobin SS, Fullmer EM: Elderly mothers caring at home for offspring with mental retardation: a model of permanency planning. American Journal on Mental Retardation 99:487-499, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

22. Moos RH, Moos BS: Family Environment Scale Manual, 2nd ed. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986Google Scholar

23. Katz MM, Lyerly SB: Methods for measuring adjustment and social behavior in the community:1. rationale, description, discriminative validity, and scale development. Psychological Reports 13:503-535, 1963Google Scholar

24. Zarit SH, Zarit JM: The memory and behavior problem checklist and the burden interview. Technical Report. University Park, Pennsylvania, School of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University, 1983Google Scholar

25. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rupp A, et al: The epidemiology of mental disorder treatment need: community estimates of "medical necessity," in Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses. Edited by Gavins A, Henderson, S. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar

26. Heller T, Factor A: Aging family caregivers: support resources and changes in burden and placement desire. American Journal on Mental Retardation 98:417-426, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lefly HP: Family Caregiving in Mental Illness. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

28. Bebbington P: The need for psychiatric treatment in the general population, in Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses. Edited by Gavins A, Henderson S. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar

29. Kasper JD, Steinwachs DM, Skinner EA: Family perspectives on the service needs of people with serious and persistent mental illness: II. needs for assistance and needs that go unmet. Innovations and Research 1:21-33, 1992Google Scholar

30. Kilian R, Lindenbach I, Lobig U, et al: Self-perceived social integration and the use of day centers of persons with severe and persistent schizophrenia living in the community: a qualitative analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:454-552, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Seltzer GB, Essex EL: Service needs of persons with mental retardation and other developmental disabilities, in Living in the Community With Disability: Service Needs, Use, and Systems, Edited by Allen S, Mor V. New York, Springer, 1998Google Scholar

32. Albert M, Becker T, McCrone P, et al: Social networks and mental health service utilization: a literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 44:248-266, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Engelhardt J, Brubaker TH, Lutzer V: Older caregivers of adults with mental retardation: service utilization. Mental Retardation 26:191-195, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

34. Thorncroft G, Johnson S, Leese M, et al: The unmet needs of people suffering from schizophrenia, in Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses. Edited by Andrews G, Henderson S. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar