Clinical Utility and Policy Implications of a Statewide Mental Health Screening Process for Juvenile Offenders

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study examined the utility of screening adjudicated juvenile offenders for mental health symptoms at intake to the State of Washington Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration. The authors assessed the ability of a screening measure, the Massachusetts Youth Screening Inventory, second edition (MAYSI-2), to identify youths with mental health problems and co-occurring substance use problems. This study also examined the relationship of these symptoms to treatment utilization both before and after intake to the juvenile justice system. Ethnic and gender differences in the screening results were studied. METHODS: The MAYSI-2 was administered to 1,840 youths consecutively admitted to state custody. Cluster analysis was used to group the youths by mental health symptom status, and the relationship between symptoms and treatment utilization was tested in the groups identified in the cluster analysis. RESULTS: Youths who reported a high level of mental health symptoms, with or without co-occurring substance use problems, were more likely to have received previous mental health treatment than youths with a low level of mental health symptoms. Youths with a high level of mental health symptoms were more likely to receive extraordinary sentences and were thus less likely to be eligible for community transition programs than youths with a low level of mental health symptoms. Significant gender and ethnic differences in mental health symptom reporting on the screening inventory were found. Female offenders were significantly more likely than male offenders to report a high level of symptoms, and Hispanic youths were significantly less likely than youths in other ethnic groups to report a high level of symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: The MAYSI-2 has utility in identifying youths in the juvenile justice system who have mental health problems, and MAYSI-2 results are related to use of treatment services both before and after intake to the juvenile justice system. Ethnic and gender differences in MAYSI-2 reporting must be considered in interpreting mental health screening data.

In 1998 the State of Washington, in collaboration with the investigators, implemented a statewide mental health screening process for youths served by the State of Washington's juvenile justice system. The study reported here explored the utility of such screening in identifying youths with mental disorders and examined the effect of psychiatric symptoms on the course of services for youths in the juvenile justice system.

National attention has focused increasingly on the need for mental health screening in the adult correctional and juvenile justice systems (1,2,3). Identifying which juvenile offenders have a mental disorder can have serious implications for the safety of the youth and of those involved with the youth's care. A youth may be dangerous to himself or herself through suicidal behavior or dangerous to others because of angry or aggressive behavior. Emotional states, including depressed mood and anxiety, which could be related to a recent trauma or to the current incarceration, have often been found to be related to self-harm or harm to others (4,5,6).

Because of these risks and the need to comply with court rulings (7), most states and national standard-setting organizations have required that every youth entering a juvenile justice facility be screened for suicide risk, substance abuse, and other mental and emotional disturbances. Such screening has typically been used to identify youths in need of special staff attention, monitoring, immediate (emergency) treatment, or more comprehensive mental health assessment. Screening tools have also allowed juvenile justice agencies and researchers to gather data on the mental and emotional characteristics of juvenile offenders in their care, and these data may be used in the design of services (8,9).

Estimates of the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders among youths in incarcerated populations have ranged between 20 percent and 60 percent (8,10,11,12). The variance in prevalence estimates can be partly attributed to the purpose of the screening program and the types of measures used. For example, general measures of psychopathology, such as the Child Behavior Checklist (13), may yield high estimates of the percentage of youths with "clinical elevations." In a study by Atkins and colleagues (14), estimates of the prevalence of psychopathology among youths served by the juvenile justice system in South Carolina were comparable to estimates for youths served by community mental health clinics and psychiatric hospitals, with 72 percent of the youths in the juvenile justice system classified as mentally ill. Standardized measures of psychopathology such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (15) have yielded high rates of psychopathology among incarcerated youths (11,16,17) because these instruments include items measuring the symptoms of disruptive behavior disorders, which occur almost universally among youths in state custody.

Measures that identify such large proportions of youths in juvenile justice settings as being mentally ill are useful in informing public policy and aiding in the understanding of the outcomes and effects of psychopathology in adolescence. However, the clinical utility of these inclusive screening measures in rehabilitative practice within juvenile institutions is limited. Grisso and colleagues (6) developed the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument, second edition (MAYSI-2), to address the clinical and pragmatic need to identify youths in juvenile justice systems who are experiencing symptoms of a mental health disorder other than the conduct problems that led to entry to the system. Similar projects have demonstrated the utility of screening instruments that identify the affective, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms associated with an increased need for specialized services (18).

The implementation of a systemwide mental health screen in a juvenile justice system requires a screening instrument that provides an unbiased estimate of the need for further assessment and treatment across ethnicity and gender. African-American, Hispanic, and Native-American youths, who are overrepresented in juvenile justice settings and underrepresented in mental health treatment, are at risk of being overlooked by mental health screening methods and policies (10,19,20,21). The instrument used in a systemwide screening should take this risk into account. In contrast, female juvenile offenders have been identified as experiencing high rates of mental health symptoms compared with male offenders (5,11,20). A systemwide screening instrument should capture these gender differences while also discriminating between girls with behavior problems and those with mental health symptoms that require specialized treatment.

The study reported here was based on an evaluation of the MAYSI-2 for use in the State of Washington's juvenile justice system. Before committing to the continued use of the instrument, state officials had specific questions about the efficacy and effectiveness of the screening. Those questions formed the basis of the evaluation and of this report. Other questions, including when and how often the instrument should be administered and whether the results were related to the prevalence of criminal behavior and recidivism, could not be answered with the available data or were not considered by state officials as crucial in deciding whether to continue using the screening instrument.

We addressed three study questions in this evaluation. First, can youths with serious emotional and behavioral disturbance be identified through a systemwide screening, and to what extent can the screen identify a group or groups of youths whose need for specific psychiatric services distinguishes them from the majority of incarcerated youths? Second, do youths who report mental health symptoms during screening differ in demographic characteristics from those who do not, and do demographic differences in the screening results reflect actual differences in prevalence or are they related to screening bias? Third, to what extent does the mental health screening reveal differences in treatment already present in the system that can be highlighted for enhancement, continuation, or termination, or, in other words, does the presence of psychiatric symptoms affect the course of rehabilitation?

Methods

Participants

A total of 1,840 youths who were consecutively admitted to custody of the State of Washington's juvenile justice system between September 1, 1997, and September 28, 1998, were given the MAYSI-2 as a screening instrument. Screening sites included juvenile justice secure institutions, work camps, regional parole offices, and residential care placements operated under contract with the state juvenile justice system. MAYSI-2 scores were entered into a database without including the youth's name or home residence or other identifying information. Identification numbers issued by the juvenile justice system were used to match MAYSI-2 data with demographic, risk, crime, and placement information from the state juvenile justice information management system, an electronic database that includes records of the criminal and placement histories of all youths served by the agency.

A subset of 222 youths completed a diagnostic mental health screening instrument. Data from the diagnostic screening were also included in the evaluation database without identifiers. The diagnostic screening was administered by county detention staff before the youth's assignment to the juvenile justice system. Youths with diagnostic screening data who were also given the MAYSI-2 were included in this study. A total of 1,798 youths (97 percent) included in the data set had complete data on MAYSI-2 results, demographic characteristics, and criminal history and placement variables. The data set used in this study was transferred electronically from the state juvenile justice system to the authors and contained no identifying information. Therefore, the University of Washington human subjects division certified that the research was exempt from the requirement for informed consent of the youths.

A total of 92 percent (N=1,640) of the youths represented in the data set were male; 55 percent (N=988) were Caucasian, 19 percent (N=344) were African American, 15 percent (N= 269) were Hispanic, 6 percent (N= 112) were Native American, and 5 percent (N=85) were Asian. The mean±SD age of the youths who completed the screening was 16.7± 1.6 years.

Measures

The MAYSI-2 was developed to identify youths in the juvenile justice system who have potential mental health care needs. The MAYSI-2 is a 52-item, self-report, yes-no questionnaire developed with norms that allow its use with juvenile offenders. Respondents are asked if they have had specific experiences "within the past few months." Answers on the MAYSI-2 contribute to scores on seven scales: alcohol or drug use, angry-irritable, depressed-anxious, somatic complaints, suicidal ideation, thought disturbance, and traumatic experiences. The MAYSI-2 is not intended to provide psychiatric diagnoses but instead to identify youths who are experiencing current mental or emotional distress or problematic behavior. High MAYSI-2 scores can indicate either of two levels of clinical concern: scores at or above the 85th percentile in a juvenile justice population are designated as "caution scores," and scores at or above the 95th percentile constitute "warning scores." The reliability and validity of the MAYSI-2 have been examined and reported by its authors (6).

The diagnostic mental health screen is an interview administered by juvenile justice staff to ascertain the mental health treatment history of youths entering the juvenile justice system.

The state juvenile justice information management system is a computer database that includes records of the criminal and placement histories of youths served by the juvenile justice system. The database indicates the youth's number of previous offenses and whether the youth has received an extraordinary sentence, which is given when a judge determines that a "manifest injustice" would occur if a youth were given only the standard range of confinement for a given offense. In addition, this database includes the youth's demographic data and community risk assessment scores. The community risk assessment was developed and is administered by the state juvenile justice system to determine the risk to the community posed by the youth. The risk assessment yields a composite score that takes into consideration the youth's previous offenses, the seriousness of the current offense, the age of the offender, the presence of substance abuse, the presence of sexual offenses, and staff ratings of the youth's behavior in juvenile justice institutions. Records of recommendations for drug and alcohol treatment made at the youth's admission to custody of the juvenile justice system were the only records of treatment referrals kept in the database at the time this study was conducted.

Results

Cluster analysis

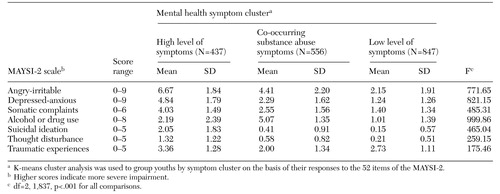

K-means cluster analysis was used to identify groups of youths on the basis of their responses to the 52 MAYSI-2 items. Three groups were requested in the analysis on the basis of an a priori decision to identify youths with mental health symptoms, substance abuse symptoms, and no mental health or substance abuse symptoms. The MAYSI-2 scale scores for the three cluster groups were compared to determine whether the cluster groups matched the a priori assumptions. The results of the comparison are summarized in Table 1. The three-cluster solution included 437 youths (24 percent) with high scores for mental health symptoms on all MAYSI-2 scales (the high mental health symptoms group) and 556 youths (30 percent) with high substance use scores and scores for mental health symptoms that were lower than those of the 437-member group but still clinically elevated (the co-occurring symptoms group). Finally, 847 youths (46 percent) with average elevations below the clinical threshold for all MAYSI-2 scales constituted the low symptoms group.

To further validate the cluster results, the prevalence of previous mental health treatment was compared by cluster group in a subset of youths who had completed the diagnostic mental health screening interview. The prevalence of previous mental health treatment was consistent with the cluster groups. A total of 90.9 percent (N=48) of the youths in the high mental health symptoms group and 74.5 percent (N=75) of the youths in the co-occurring symptoms group had received mental health services, compared with 55.1 percent (N=38) of those in the low symptoms group, a significant difference (χ2=17.18, df= 2, p<.001, N=222). Cluster membership was used in subsequent analyses as the dependent or grouping variable.

Demographic characteristics

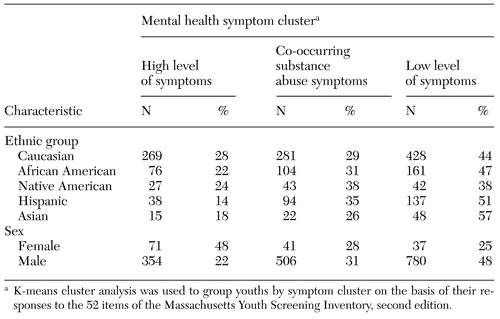

Cluster membership was cross-tabulated with gender to determine differences in gender distribution across groups. As Table 2 shows, female offenders were more likely to be included in the high mental health symptoms group, and male offenders were more likely to be included in the low symptoms group (χ2=55.01, df=2, p<.001, N=1,789).

Multinomial logistic regression was used to determine whether ethnicity predicted cluster membership. Overall, ethnicity was a significant predictor of mental health status as measured by the MAYSI-2 (χ2=31.36, df= 8, p<.001, N=1,788). Compared with youths from all other ethnic groups, Caucasian youths were more likely to be represented in the high mental health symptoms group (β=.70, p<.05) and Native-American youths were more likely to be included in the co-occurring symptoms group (β=.80, p<.05). Hispanic and Asian youths had comparatively low representation in the high mental health symptoms group. African-American youths were neither more nor less likely to appear in any cluster, compared with youths from other ethnic groups.

An additional analysis was conducted with data from the diagnostic mental health screening interview for 222 youths from the various ethnic groups to determine whether the ethnic groups differed in the use of mental health services before intake to the juvenile justice system. Caucasian youths were most likely to report having received mental health services (81 percent, or 108 of 133 youths) than youths from all of the other ethnic groups. Hispanic youths were the least likely to receive services (42 percent, or five of 12 youths) compared with youths from other ethnic groups. A total of 75 percent of African-American youths (38 of 51 youths), 69 percent of Native-American youths (11 of 16 youths), and 50 percent of Asian youths (five of ten) had received mental health services; these service utilization differences were significant (χ2=18.04, df=4, p<.001).

Course of rehabilitation

Cluster membership was used to compare the youths on indicators of use of rehabilitative services after intake to the juvenile justice system. Youths in the co-occurring symptoms group were significantly more likely to be referred for substance abuse treatment (354 of 376 youths, or 94 percent) than youths in the high mental health symptoms group (204 of 285 youths, or 72 percent) or the low symptoms group (397 of 529 youths, or 75 percent) (χ2=68.29, df=2, p<.001, N=1,788). Youths in the high mental health symptoms group were significantly more likely to receive an extraordinary sentence (82 of 235 youths, or 35 percent) than youths in the co-occurring symptoms group (54 of 252 youths, or 21 percent) and youths in the low symptoms group (118 of 456 youths, or 26 percent) (χ2=11.71, df=2, p<.01, N=943).

Analysis of variance found no significant differences between groups in the mean number of previous offenses, with the three groups averaging between six and seven criminal offenses before the current intake to the juvenile justice system (mean± SD=6.33±3.98 for the high mental health symptoms group, 6.99±4.19 for the co-occurring symptoms group, and 6.73±4.36 for the low symptoms group). Univariate tests were used to compare the three groups' risk assessment scores at intake to the juvenile justice system, and repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine group differences over time, from intake to follow-up at 90 days before the earliest release date. At intake to the juvenile justice system, the youths in the co-occurring symptoms group received significantly higher risk scores (mean ±SD=26.23±6.81) than the youths in the high mental health symptoms group (mean±SD=22.94± 8.21) and the youths in the low symptoms group (mean±SD=22.95±8.44) (F=16.38, df=2, 1,788, p<.001). The mean±SD risk scores at follow-up were 22.46±11.43 for the high mental health symptoms group, 22.72±11.84 for the co-occurring symptoms group, and 18.16±10.43 for the low symptoms group. The results of the repeated-measures ANOVA showed that risk scores differentially changed over time by cluster group (multivariate F=14.21, df=2, 1,050, p<.001). Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc tests showed that the three groups significantly differed from each other in change in risk scores over time.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the clinical utility of a systemwide mental health screen for youths served by the State of Washington's juvenile justice system. In addition, the effect of psychiatric symptoms on the course of treatment among youths served by the juvenile justice system was explored.

The results showed that the screening instrument, the MAYSI-2, yielded scores that could be clustered to identify youths with a high level of mental health symptoms, youths with a low level of mental health symptoms, and youths with significant substance use symptoms co-occurring with mental health symptoms. External validity of the cluster groups was demonstrated in an analysis of data about previous receipt of mental health treatment that showed distinctions between the cluster groups in a subset of youths. The vast majority of youths who reported a high level of mental health symptoms had previously received treatment, but only about half of the youths with a low level of mental health symptoms had received treatment. This difference likely reflects the high proportion of youths with externalizing symptoms who are seen for mental health care.

Analyses of the demographic characteristics of the youths in the three cluster groups revealed significant gender differences. Nearly half of the female offenders in the study were included in the high mental health symptoms group. This finding is consistent with those of other studies of juvenile justice populations (5,22). Female offenders have been consistently found to demonstrate higher rates of mental health symptoms than male offenders. Possible explanations for this discrepancy include the "relative deviance" hypothesis, which suggests that girls are far less likely than boys to demonstrate behaviors that lead to incarceration and that when they do, such behaviors likely represent a higher level of psychopathology (23). Girls have also been found to have higher rates of reported trauma than boys (5,24), which may lead to higher rates of reported symptoms of affective disturbance and anxiety.

Ethnic differences were also found in this study. Overall, ethnicity predicted differential classification by the MAYSI-2. Caucasian youths were more likely to report a high level of mental health symptoms, and Native-American youths were overrepresented in the group with co-occurring mental health and substance use symptoms. Hispanic and Asian youths were the least likely to self-report a high level of mental health symptoms.

Several explanations for the effect of ethnicity must be considered. First is the possibility of bias in the instrument. The MAYSI-2 was administered solely in English for this project and therefore may have been less reliable and valid for youths who speak English as a second language. The MAYSI-2 was developed with norms for diverse populations throughout the country, but potentially important differences in culture, immigrant status, dialect, and country of origin may have affected the results for the youths in the specific region where the study was conducted.

Second, the ethnic differences in symptom reporting could be related to differences in previous treatment experiences. The significantly lower rates of previous use of mental health services among the Hispanic youths may have made them less likely to identify and report symptoms. The overrepresentation of Caucasian youths in the group with a high level of mental health symptoms may also be related to their higher rate of previous mental health treatment and previous exposure to symptom identification.

Finally, the ethnic differences may be a statistical artifact rather than a clinically significant finding. Elevations in mental health symptoms and in co-occurring symptoms were separated by the study's statistical technique but may actually be closely related. Some youths may be more prone than others to attribute more of their mental health symptoms to substance use, particularly youths who have not received mental health treatment but have received substance abuse treatment.

Self-reported psychiatric symptoms were significantly related to treatment indicators within the juvenile justice system. Despite similar numbers of previous offenses across the cluster groups, sentencing decisions and security classifications differed across the groups. Youths who were identified as having a high level of mental health symptoms were more likely to receive an extraordinary sentence, which would result in longer incarceration. The data did not provide a clear explanation of the mechanisms for this finding. However, the behavior and attitudes of youths with psychiatric symptoms may negatively affect the decisions made by prosecutors, judges, and probation officers. Youths with co-occurring symptoms had higher risk scores on admission to the juvenile justice system, thus creating additional hurdles for their movement into less restrictive rehabilitative settings within the system.

Over time, only the youths in the low mental health symptoms group averaged risk scores that were low enough to qualify for minimum-security transitional placements. These placements are a significant resource for helping youths adjust to a less structured environment and begin to reestablish connections with school, vocational programs, and treatment providers. Youths who exhibited a high level of mental health symptoms or co-occurring mental health and substance use symptoms were therefore more likely to be transitioned directly to their communities from incarceration and were less likely to receive dispositional planning involving systematic transitional stages.

A primary goal of the screening project in the State of Washington's juvenile justice system was to obtain information on the nature of existing services for youths within the juvenile justice system who exhibit symptoms of a psychiatric or substance use disorder. By reliably identifying and classifying youths who exhibit these symptoms, the juvenile justice system could begin the process of systematically assessing and planning interventions and policies affecting their care. Despite increasing evidence that the use of highly structured diversion and community-based interventions is an effective strategy for these youths (25,26), detainment in secure juvenile facilities offers an opportunity to begin focused rehabilitative efforts that could lead to more effective transitional planning. The effects of such efforts in reducing recidivism and improving developmental trajectories could be enormous.

The authors are affiliated with the division of public behavioral health and justice policy in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington, Box 358854, Seattle, Washington 98103-8652 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scores on scales of the Massachusetts Youth Screening Inventory, second edition (MAYSI-2), of youths admitted to the State of Washington Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration who were classified by mental health symptom cluster

|

Table 2. (11 of 16 youths), Race and gender of 1,789 youths admitted to the State of Washington Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration who were classified by mental health symptom cluster

1. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Mentally disordered women in jail: who receives services? American Journal of Public Health 87:604-609, 1997Google Scholar

2. Bilchik S: A juvenile justice system for the 21st century. Crime and Delinquency 44:89-101, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Wasserman GA, McReynolds L, Lucas CP, et al: The voice DISC-IV with incarcerated male youths: prevalence of disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:314-321, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brown TL, Henggeler SW, Brondino MJ, et al: Trauma exposure, protective factors, and mental health functioning of substance-abusing and dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 7:94-102, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Cauffman, E, Feldman SS, Waterman J, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder among female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:1209-1216, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Grisso T, Barnum R, Fletcher K, et al: Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument for mental health needs of juvenile justice youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:541-548, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. DaleMJ, Sanniti C: Litigation as an instrument for change in juvenile detention: a case study. Crime and Delinquency 39:49-67, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Grisso T: Juvenile offenders and mental illness. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 6:143-151, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Dembo R, Schmeidler J, Pacheco K, et al: The relationships between youths' identified substance use, mental health or other problems at a juvenile assessment center. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse 6:23-54, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Novins DK, Duclos CW, Martin C, et al: Utilization of alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment services among American Indian adolescent detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1102-1108, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Timmons-Mitchell J, Brown C, Schulz SC, et al: Comparing the mental health needs of female and male incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 15:195-202, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Ulzen PM, Hamilton H: The nature and characteristics of psychiatric comorbidity in incarcerated adolescents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:57-63, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Achenbach TM: The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment, 2nd ed. Edited by Maruish ME. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 1999Google Scholar

14. Atkins DL, Pumariega AJ, Rogers K, et al: Mental health and incarcerated youth: I. prevalence and nature of psychopathology. Journal of Child and Family Studies 8:193-204, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al: NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:28-38, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pliszka SR, Sherman JO, Barrow MV, et al: Affective disorder in juvenile offenders: a preliminary study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:130-132, 2000Link, Google Scholar

17. Rosenblatt JA, Furlong MJ: Outcomes in a system of care for youths with emotional and behavioral disorders: an examination of differential change across clinical profiles. Journal of Child and Family Studies 7:217-232, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Dembo R, Schmeidler J, Borden P, et al: Use of the POSIT among arrested youths entering a juvenile assessment center: a replication and update. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse 6:19-42, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Cunningham PB, Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG: The cross-ethnic equivalence of measures commonly used in mental health services research with children. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 4:231-239, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Gunter-Justice TD, Ott DA: Who does the family court refer for psychiatric services? Journal of Forensic Sciences 42:1104-1106, 1997Google Scholar

21. McCabe K, Yeh M, Hough RL, et al: Racial/ethnic representation across five public sectors of care for youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 7:72-82, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Cocozza JJ: Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. Seattle, National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Justice System, 1992Google Scholar

23. Dembo R, Shern D: Relative deviance and the process(es) of drug involvement among inner-city youths. International Journal of the Addictions 17:1373-1399, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Randall J, Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity and the 16-month trajectory of substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1118-1124, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Henggeler SW: Multisystemic therapy: an overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implications. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review 4:2-10, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Barnoski R: The Community Juvenile Accountability Act: research-proven interventions for the juvenile courts. Report 99-01-1204. Olympia, Wash, Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 1999Google Scholar