Case Managers' Perspectives on Critical Ingredients of Assertive Community Treatment and on Its Implementation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors sought to identify case managers' perspectives on the critical ingredients, therapeutic mechanisms of action, and gaps in implementation of the critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. METHODS: Seventy-three assertive community treatment teams that attended the 1997 National Assertive Community Treatment Conference rated the degree to which 16 clinical activities were beneficial to clients and rated the importance of 27 possible critical ingredients of the ideal team as well as the extent to which each ingredient characterized their team. RESULTS: At least 50 percent of the teams rated 24 of the 27 critical ingredients as "very important." Having a full-time nurse on the team was rated as the most important ingredient, and medication management was rated as the most beneficial clinical activity. The ratings of teams from urban and rural settings were highly correlated. Critical elements that the teams reported as being the most underimplemented included the presence of a full-time substance abuse specialist, a psychiatrist's involvement on the team, team involvement with hospital discharge, and working with a client support system. CONCLUSIONS: Case managers strongly endorsed the team approach as well as medical aspects of assertive community treatment. Despite broad consensus on the critical ingredients of the ideal assertive community treatment team, several important ingredients appear to be consistently underimplemented.

The weight of available evidence indicates that assertive community treatment is an effective community treatment model for persons with severe mental illness (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). However, although there is strong evidence that this form of treatment is successful—for example, lower rates of hospitalization and improvements in overall functioning—the essential structural and organizational program elements that underlie the effectiveness of the model have not been clearly established empirically. Few studies, either experimental (9) or quasi-experimental (10), have been conducted with the express purpose of establishing the importance of particular elements of assertive community treatment. A majority of the published studies that have attempted to identify the critical elements empirically has relied on more indirect methods—for example, meta-analyses correlating individual elements of assertive community treatment with client outcomes or with service indicators (5,11,12).

One method, suggested by Sechrest and colleagues (13), to help identify the core ingredients of an intervention is to ask informed stakeholders in the model. For example, in one study (14) assertive community treatment experts were asked to rate a list of possible critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. In a related study (15), a sample of clients was asked to nominate helpful elements of assertive community treatment. Assertive community treatment workers are another important stakeholder group that could provide a valuable perspective on the critical elements of this treatment approach. However, apart from a preliminary study of nine assertive community treatment case managers (16), assertive community treatment workers have not been surveyed about the critical ingredients of assertive community treatment.

A related area of needed research is the identification of the underlying mechanisms of action of assertive community treatment (3). Mechanisms of action are the specific clinical activities (for example, medication management) and therapeutic conditions (for example, feeling supported by the therapist) that are thought to lead to positive outcomes for clients.

Although possible mechanisms of action sometimes appear on lists of critical ingredients, such lists primarily feature easily measurable organizational, structural, and service elements that clearly differentiate between psychosocial models (14). By contrast, mechanisms of action (such as providing medications) may be shared across psychosocial program models that differ greatly in organizational or structural ingredients. Few formal attempts have been made to empirically identify the therapeutic mechanisms of action of assertive community treatment.

Accordingly, this study examined two key questions. First, what are the critical ingredients of assertive community treatment from the perspective of persons who provide these services? Second, what are the critical clinical elements or mechanisms of action that are thought to underlie the success of assertive community treatment as rated by members of assertive community treatment teams? A related question asked the degree to which the answers to the primary questions varied as a function of whether the program setting was urban or rural.

Methods

Study participants and setting

Study participants were recruited at the 12th Annual National Assertive Community Treatment Conference, held in Shanty Creek, Michigan, in June 1997. Conference participants were given written information about the study in their registration packets. Announcements about the study also were made at individual and plenary sessions of the conference. Members of the research team from the Indiana Consortium of Mental Health Services Research staffed a table throughout the conference to answer questions about the study and to distribute and collect study materials. Study participants were given a commemorative coffee mug.

Entire assertive community treatment teams—not individual team members—were the targeted group and intended level of analysis. Only teams that identified themselves as assertive community treatment teams were included in the study. Each team was asked to fill out the questionnaire as a team. Only one questionnaire was completed per team. Although we did not collect data on the number of team members who filled out each questionnaire, our impression is that the great majority of questionnaires were filled out by two or more members of a team meeting together as a group. To maintain anonymity, we did not gather information about the locations of the assertive community treatment teams; however, of approximately 130 teams that attended the conference, about 75 percent were from Michigan.

A total of 121 assertive community treatment teams completed the survey. One critical concern was whether the teams worked in programs that were faithful representatives of the assertive community treatment model. In an attempt to rule out this source of possible bias, the programs were divided into low- and high-fidelity programs on the basis of team-reported implementation of 27 putative critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. When teams reported that at least 70 percent of the 27 ingredients were characteristic or very characteristic of their assertive community treatment program, the program was classified as a high-fidelity program and was included in the analyses (N=73). Teams from low-fidelity programs (N=48) were excluded from all analyses. (The decision to use a 70 percent cutoff point was arbitrary. The decision to use the responses "characteristic" or "very characteristic" to indicate implementation parallels a scoring procedure used for the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (17). Although the analyses reported here were restricted to high-fidelity teams, analyses also were completed on the basis of the entire sample of 121. In all cases, the results were highly similar.)

Measures

An assertive community treatment questionnaire was developed for the study. Section 1 of the questionnaire assessed the degree to which 16 clinical activities typically engaged in by assertive community treatment teams—for example, providing social support or money management—were considered by the team to be beneficial. The list of typical clinical activities was generated from a review of the literature (2,14,18) and was supplemented with pilot data collected from ten assertive community treatment case managers in Indiana, who were asked to provide examples of potentially beneficial activities. Each activity was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1, extremely beneficial, to 7, no benefits. An open-ended question asked the team to nominate additional clinical activities that they considered to be beneficial. The internal consistency of the 16 clinical activity items was .88, indicating adequate reliability of measurement for these items.

Section 2 of the questionnaire assessed case managers' perspectives on the critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. The assertive community treatment teams rated 27 items that were composites of items either previously rated as critical by experts (14) or derived from the Index of Fidelity to ACT (IFACT) (11) or the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (DACTS) (17,19). Each item was rated twice on the basis of a 5-point Likert scale. The teams first rated the importance of the item to the operation of the ideal assertive community treatment team on a scale from 1, very important, to 5, not at all important. Second, the teams rated the degree to which each item was characteristic of their own team on a scale from 1, very characteristic, to 5, not at all characteristic. Internal consistency of the 27 items, when rated in terms of the items' importance to the ideal assertive community treatment team, was .78; when rated in terms of whether the items were characteristic of a team's own assertive community treatment program, internal consistency was .84. Both these numbers indicate adequate reliability of measurement for these items.

Finally, section 3 of the questionnaire asked for brief descriptive information about each team's assertive community treatment program, including information about the setting, caseload, team meetings, and staffing.

Data analysis

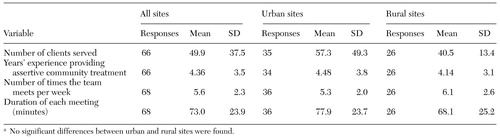

Mean ratings of organizational elements for all sites and for urban compared with rural sites are listed in Table 1. Most of the teams reported being located in urban settings (42 teams, or 57 percent). The teams reported an average caseload of 50 clients and an average of 4.4 years' experience in providing assertive community treatment. No significant differences were found between rural and urban teams.

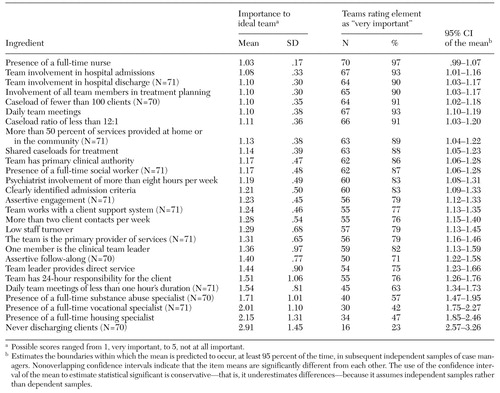

The 27 putative critical ingredients are listed in Table 2 in rank order of importance as rated by the assertive community treatment teams. An item was considered to be critical if it was rated "very important" by more than 50 percent of the teams. All but three items—presence of a full-time housing specialist, presence of a full-time vocational specialist, and never discharging clients from the team—were rated as critical. The five items of highest importance were presence of a full-time nurse, team involvement in both hospital admission and discharge decisions, shared caseloads for treatment planning, and small caseloads for each team. The data were examined for possible differences in importance ratings according to whether the team was located in an urban or a rural setting. The correlation between the importance ratings of rural and urban teams was large and significant (r=.91, p<.05). Urban and rural teams' importance ratings did not differ significantly for any of the 27 t test comparisons. Because there were so many comparisons, alpha was set at .01 for the t test analyses, to guard against type I error. Levene's test for equal variances was conducted before the independent-samples t statistic was computed. When the results of Levene's test were significant, a t test calculation was used that did not assume equal variances. This t test also produces noninteger degrees of freedom.

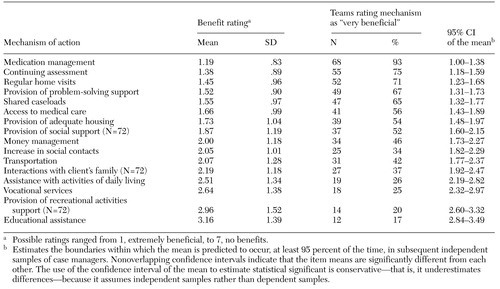

The 16 possible therapeutic mechanisms of action are listed in Table 3 in rank order of the degree to which each was rated as being beneficial. Eight items were rated as extremely beneficial by more than 50 percent of the teams. Medication management was rated as the most beneficial clinical activity. At least two-thirds of the teams rated continuing assessment, regular home visits, and provision of problem-solving support as extremely beneficial. Growth oriented items—educational assistance and providing support for recreational activities—had the lowest benefit ratings. Providing vocational services also received relatively low ratings.

Assertive community treatment teams suggested additional beneficial clinical ingredients. Suggestions were grouped into six emergent categories: other (31 percent); opportunities for individual, group, or family therapy (17 percent); assistance with activities of daily living (17 percent); providing liaison with community agencies (13 percent); educational services (12 percent); and supporting increased peer interaction and support (10 percent). Educational assistance and assistance with activities of daily living were basically identical to two of the original 16 categories.

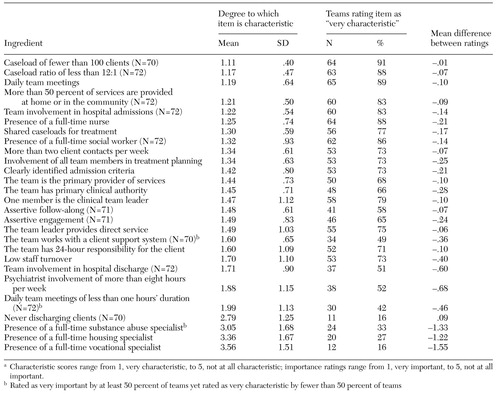

The characteristic ratings for the 27 possible critical ingredients and the mean difference between an ingredient's importance and characteristic ratings are summarized in Table 4, rank ordered by characteristic rating. The teams reported some degree of underimplementation of assertive community treatment—that is, a positive difference between importance and characteristic ratings—for all items except never discharging clients. However, at least 50 percent of the teams rated 21 of the 27 items as very characteristic of their program, indicating that most sites reported faithful implementation of most of the items.

Of the six items not rated as very characteristic by more than 50 percent of the teams, three had been rated as critically important. These items and the proportion of teams that rated them as very characteristic were working with a client support system (49 percent), having meetings of less than one hour's duration (42 percent), and presence of a full-time substance abuse specialist (33 percent).

Two other critical ingredients showed evidence of underimplementation, as indicated by differences exceeding .5 of a rating point between teams' importance and characteristic ratings. In addition to the large mean difference for the presence of a substance abuse specialist (−1.33), psychiatrist involvement of at least eight hours (.68), and team involvement in hospital discharge (.60) showed large differences between ratings.

Finally, differences in characteristic ratings between urban and rural teams were examined. The correlation between the characteristic ratings of rural and urban teams was large and significant (r=.94, p<.05). One of 27 t test comparisons was significant: urban teams were significantly more likely to rate never discharging clients as characteristic (2.4 versus 3.4, t=3.1, df=57, p<.01).

Discussion and conclusions

This study attempted to identify the critical ingredients of assertive community treatment from the perspective of members of the assertive community treatment team. The results agreed very well with the most systematic previous attempt to identify critical ingredients by using assertive community treatment experts (14). Nearly 90 percent of the items, largely derived from the results of the previous expert survey, were rated as critical. Thus there is now converging evidence from two separate surveys of informed stakeholders to validate the critical importance of these ingredients. Moreover, importance ratings were very consistent across programs. Urban and rural assertive community treatment teams agreed closely on the important ingredients (r=.91) and displayed no significant pairwise differences in importance ratings. Overall, the results both validate the findings of the expert survey and suggest that there is broad consensus about the essential ingredients of assertive community treatment.

Many hallmarks of the assertive community treatment model received strong endorsements from the assertive community treatment teams in this study—for example, a small client-to-staff ratio and having most services provided in the community. Of particular note, and consistent with the results of the expert survey (14), the team approach emerged as being critical. Four of the ten top-rated items concerned aspects of the team approach—shared caseloads, having all members involved in treatment planning, giving the team primary clinical authority, and having daily team meetings. Similarly, the teams strongly endorsed medical aspects of the model. The three items ranked as being of highest importance dealt with medical aspects of assertive community treatment: the importance of having a nurse on the team and of team involvement in hospital decisions to admit and discharge clients. Moreover, the teams rated medication management as the single most beneficial clinical ingredient. Experts and other observers also have noted the critical importance of medical features of the assertive community treatment model (2,14,18,20).

There was less consensus about the importance of some proposed elements of assertive community treatment teams. Neither vocational specialists nor housing specialists were rated as critical to assertive community treatment, although, consistent with the expert survey, there was a significant minority view that these are critical specialties (14). In addition, only 23 percent of the teams rated never discharging clients from assertive community treatment as very important, despite the fact that a no-discharge model previously has been singled out as key feature of assertive community treatment (18). Experts also downrated this traditional aspect of assertive community treatment (14). This change in the importance of a no-discharge policy is consistent with recent evidence showing that graduation is possible for some clients of assertive community treatment programs (10).

The teams in this study consistently reported underimplementing elements of assertive community treatment. Of most interest, the teams reported that several critical elements were underimplemented—involvement in hospital discharge, psychiatrist involvement of at least eight hours, daily meetings of less than one hour's duration, working with a client support system, and presence of a full-time substance abuse specialist—as indicated either by less than half of the teams rating the element as very characteristic or by large differences between importance and characteristic ratings. Thus, despite clear agreement about what the critical elements are, there were indications that several of these critical elements are not being implemented consistently.

Because deficiency in the implementation of assertive community treatment also has been related to poorer outcomes (11), these results are troubling. However, future research is needed both to verify these results on the basis of more objective methods and to identify underlying barriers to full implementation. Anecdotally, teams reported system or organizational barriers to becoming closely involved in hospital discharge. Many teams also reported general difficulty obtaining qualified staff, especially in securing adequate psychiatrist time and participation of specialists. However, it is also possible that underimplementation in some areas may simply reflect natural lags in adjusting implementation to match changing conceptions of the model. For example, the critical importance of having a substance abuse counselor and of interacting with client support systems are both areas of increasing emphasis for assertive community treatment (14).

The most speculative results concern the possible therapeutic mechanisms of action. Assertive community treatment teams rated medication management as the most beneficial clinical activity. That is, when directly asked, more than 90 percent of assertive community treatment teams viewed medication management as extremely beneficial. Several other ingredients that have previously been noted as important (18,20,21) also were rated as extremely beneficial by at least 50 percent of assertive community treatment teams—for example, home visits, shared caseloads, and ongoing assessments. The rating of the provision of support—general problem-solving support and social support—as extremely beneficial is particularly interesting. The potential benefit of social support is consistent both with the hypothesis that assertive community treatment may work by helping to create a functioning social network and safety net around the person (22) and with clients' reports that having someone to talk to is a key helping ingredient of assertive community treatment (15). We hope that the findings reported here stimulate investigators to examine some of the promising candidate mechanisms of action tentatively identified. Current research has largely ignored the exploration of potential mediating variables underlying the effectiveness of assertive community treatment, despite their clear importance to understanding therapeutic change in assertive community treatment (3,23).

Few significant differences were found between rural and urban assertive community treatment programs. Rural and urban teams agreed closely on both the importance ratings and the characteristic ratings for the 27 putative critical ingredients. The only significant finding was that urban teams reported that they were more likely to adhere strictly to a no-discharge policy. However, the samples were small, and some real differences may have been undetected—for example, when the full sample of 121 teams was used, there was a significant difference in caseload between rural and urban teams: the rural teams had smaller caseloads.

The study had several limitations. All the data were self-reported. We were unable to verify the self-reported degree of implementation, for example, and cannot rule out social desirability bias or other reporting errors (24,25), although data were collected anonymously to help reduce social desirability bias. Another limitation was that the participating teams may not have been representative of assertive community treatment programs. The teams in the sample were predominantly from Michigan, and results could differ for teams based more closely on the original PACT model (26). Finally, not all the teams may have been able to comment knowledgeably on the usefulness of specific mechanisms of action—for example, vocational services—especially if they did not provide the service or had little exposure to those aspects of the model.

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study were made available by the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research, which is partly funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant MH-51669); the Research and University Graduate School and the College of Arts and Sciences at Indiana University, Bloomington; the Dean of the Faculty at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis; and the Indiana State Division of Mental Health. The study was also supported by grant K0201289 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Pescosolido through an independent scientists award. The authors thank Gary Bond, Ph.D., and Betsy McDonel, Ph.D., for their helpful comments.

Dr. McGrew is associate professor of psychology at the Purdue University School of Science, Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, 402 North Blackford Street, LD 3124, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202-3275 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Pescosolido is chancellor's professor of sociology at Indiana University in Bloomington. Dr. Wright is associate professor of sociology at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis.

|

Table 1. Organizational elements of rural and urban assertive community treatment teamsa

a No significant differences between urban and rural sites were found.

|

Table 2. Rank ordering of importance of putative critical ingredients of assertive community treatment based on ratings of importance for an ideal program by 72 teams

|

Table 3. Rank ordering of perceived benefit of putative therapeutic mechanisms of action based on ratings by 73 assertive community treatment teams

|

Table 4. Implementation of putative critical ingredients of assertive community treatment, as reported by 73 assertive community treatment teams, and difference between importance and characteristic ratingsa

a Characteristic scores range from 1, very characteristic, to 5, not at all characteristic; importance ratings range from 1, very important, to 5, not at all important.

1. Bond GR, McGrew JH, Fekete DM: Assertive outreach for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:4-16, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Test MA: Training in community living, in Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Edited by Liberman RP. New York, Macmillan, 1992Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Herdelin AC, Scott DL: Experimental studies of the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT): a meta-analysis. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 10:53-89, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Latimer E: Economic impacts of assertive community treatment: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:443-454, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bedell JR, Cohen NL, Sullivan A: Case management: the current best practices and the next generation of innovation. Community Mental Health Journal 36:179-194, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ziguras S, Stuart G: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410-1421, 2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141-159, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Hu TW, Jerrell JM: Estimating the cost of impact of three case management programmes for treating people with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 173 (suppl 36):26-32, 1998Google Scholar

10. Salyers MP, Masterton TW, Fekete DM, et al: Transferring clients from intensive case management: impact on client functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:233-245, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen LL, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:670-678, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. McGrew JH, Bond GR: The association between program characteristics and service delivery in assertive community treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:175-189, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sechrest L, West SG, Phillips MA, et al: Some Neglected Problems in Evaluation and Research: Strength and Integrity of Treatments, vol 4. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1979Google Scholar

14. McGrew JH, Bond GR: Critical ingredients of assertive community treatment: judgments of the experts. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:113-125, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McGrew JH, Wilson R, Bond GR: Client perspectives on helpful ingredients of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:13-21, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Prince PN, Demidenko N, Gerber GJ: Client and staff members' perceptions of assertive community treatment: the nominal groups technique. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 23:285-288, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Witheridge TF: The "active ingredients" of assertive outreach. New Directions for Mental Health Services 52:47-64, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Teague GB, Drake RE, Ackerson TH: Evaluating use of continuous treatment teams for persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 46:689-695, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Allness DJ, Knoedler WH: The PACT Model of Community-Based Treatment for Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illness: A Manual for PACT Start-up. Arlington, Va, National Association of the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

21. Stein LI, Test MA: The Training in Community Living model: a decade of experience. New Directions for Mental Health Services 26:1-98, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Sullivan WP: Communities of care: a theoretical perspective on case management models in mental health. Advances in Medical Sociology 6:37-79, 1995Google Scholar

23. Ingram RE, Hayes A, Scott W: Empirically supported treatments: a critical analysis, in Handbook of Psychological Change: Psychotherapy Processes and Practices for the 21st Century. Edited by Snyder CR, Ingram RE. New York, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

24. Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, et al: Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research 2:75-87, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bond GR, Williams J, Evans L, et al: Psychiatric rehabilitation fidelity toolkit. Cambridge, Mass, Human Services Research Institute, 2000Google Scholar

26. Stein LI, Test MA: An alternative to mental health treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar