Professionals' Responsibilities in Releasing Information to Families of Adults With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Statutes, ethical standards, and local confidentiality guidelines have been developed to guide providers' decisions about releasing information from mental health records. However, confidentiality policies often do not specifically discuss the release of confidential information to the families of persons with mental illness. This study examined how providers and family members interpret and implement confidentiality policies about the release of information to families. METHODS: Self-administered surveys were completed by 59 providers from outpatient, partial hospitalization, and case management programs in Pennsylvania. In-depth interviews were also conducted with a subsample of eight providers. In addition, 68 families of persons with mental illness receiving services from these providers completed self-administered surveys. RESULTS: Ninety-five percent of the providers interpreted confidentiality policies conservatively, believing that they could not share confidential information without the consent of the client, However, 54 percent were confused about the types of information that are confidential. Implementation of confidentiality policies varied among the providers. Regression analysis indicated that providers' perceptions of confidentiality as a barrier to collaboration were significantly associated with their attitudes toward collaboration between the providers, consumers, and family members. Few families understood the requirements of confidentiality policies or the types of information that are confidential. CONCLUSIONS: Confidentiality policies may be posing a barrier to collaboration between providers, consumers, and family members, which has been recommended by various experts for the treatment of mental illness. Clear guidelines for the release of confidential information to families are needed.

Despite efforts to reduce the stigmatization faced by persons with mental illness, consumers still encounter discrimination in most life domains (1,2). For this reason, it is believed that consumers will not seek treatment without the promise that what they disclose will be kept confidential (2,3,4). However, some disclosure of confidential treatment information is necessary for the provision of high-quality mental health care. For example, engaging consumers in the development of support networks to assist them in monitoring and managing symptoms of their illness is an important part of recovery. Without information about consumers' illness and treatment, however, the support that families can offer is limited.

Research indicates that more than 50 percent of consumers live with their families (5,6,7) and that 77 percent have regular contact with their families (8). Consequently, families tend to be primary members of consumers' support networks (9,10). Although studies show that collaboration between the provider, the consumer, and the consumer's family leads to fewer relapses and rehospitalizations (11,12,13) and current best practice guidelines recommend involving families in treatment (14,15,16,17,18), few mental health providers routinely implement these guidelines (19). One barrier to family involvement cited by providers and families is unclear confidentiality policies (3,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28).

Confidentiality laws vary tremendously in nature, scope, and strength and have been described as "erratic," "confusing," and "inconsistent" (29). In 1996 Congress acknowledged the inadequacies of these laws and mandated the development of the first federal privacy protection for health information (30). Although the Federal Privacy Rule provides some guidance for releasing information to families, it was designed to set a floor for privacy protection and therefore does not preempt state laws that define more conservative standards.

Pennsylvania is one of 29 states with no statutory language guiding the release of information to families (31,32). Although states that do have statutory language differ in their procedures for releasing information to families, most require or strongly encourage written consent (33). In states in which statutes are unclear or inconsistent, some local mental health systems have developed guidelines for interpreting the laws.

Although the complexities of confidentiality policies are believed to hinder necessary communication between providers and families of persons with mental illness, little research exists examining how providers and families interpret and implement these policies. In this exploratory study we used cross-sectional analysis to examine providers' perceptions, understanding, and implementation of confidentiality and to explore factors that influence providers' interpretation and implementation of these policies. Families were also asked about their understanding of confidentiality and how providers have discussed these policies with their mentally ill relative.

Methods

Provider sample

Clinical staff from outpatient, partial hospitalization, and case management programs in two mental health agencies outside Philadelphia completed a self-administered survey in September 1999 (59 respondents, for a response rate of 84 percent). Approval was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania's institutional review board. Most providers who refused to participate worked in outpatient programs. Both agencies provided general training on confidentiality, reimbursed providers for work with families, and had no written policies, guidelines, or training for interpreting Pennsylvania statutes about the release of information to families.

In-depth interviews were conducted with eight providers. The subsample was selected on the basis of providers' survey responses, which were used to divide the providers into two categories: those who perceived confidentiality policies as a barrier to collaboration and those who did not. The subsample was expected to represent providers who had a variety of views about the release of information to families of persons with mental illness.

Family sample

Families were eligible for the study if they had a relative aged 18 years or older with a DSM-IV diagnosis of a schizophrenia-spectrum or major mood disorder who was receiving services from programs participating in the study. Family participants were required to have weekly contact with their ill relative, either in person or by telephone.

Procedures for recruiting eligible families included random selection of clients' files by providers, determination of whether families were eligible, and introduction of a research authorization form to the client, which permitted researchers to contact them. Providers were asked to repeat this procedure until they obtained three authorizations.

Of 174 clients who signed an authorization form, 102 (59 percent) provided permission to contact their family. Clients who refused stated that they were uncomfortable with their family being contacted or did not want to disturb them. In addition, 26 (26 percent) of the 102 families who were contacted refused to participate, and eight (8 percent) were not eligible for the study. Informed consent was received by telephone, and families completed the survey by mail. The final sample was 68 families.

Measures

The confidentiality process measures are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Both providers and families were asked to respond to five statements to assess their interpretation of confidentiality policies. Two items assessed perceptions of whether confidentiality policies pose a barrier to collaboration, and three items measured understanding of the types of information that are confidential. Correct responses to these items were defined by the most conservative interpretation of existing law—specifically, that written consent is required for the release of identifying information from a medical record to any third party, including family members. Correct responses were summed to create a score ranging from 0 (all items incorrect) to 3 (all items correct).

Providers and family respondents were asked five questions to assess their implementation of confidentiality policies. In addition, providers who were interviewed were asked how and when information was released to families, factors that influenced whether they shared information, and strengths and weaknesses of the agency's procedures for releasing information to families.

Sociodemographic variables including gender, race, and education were measured. Providers' attitudes toward collaboration were assessed by measuring beliefs about causes of mental illness, given that research indicates that providers who believe that families cause mental illness are less likely to collaborate (34,35,36). Rubin's scale (37), which consists of Likert-format statements assessing degree of agreement with environmental and biological factors as causes of mental illness, was adapted and summed to obtain a provider attitude score (Cronbach's alpha=.73). All measures were pretested among ten providers and ten family members from nonparticipating agencies.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted in the provider and family samples by using SPSS (38). Three linear regression models were constructed to examine whether providers' attitudes toward collaboration were associated with three dependent variables—perception of confidentiality as a barrier, understanding of the types of information that are confidential, and implementation of confidentiality policies, with race, gender, education, professional discipline, and program affiliation controlled for. Missing data were handled through pairwise deletion.

Results

Characteristics of provider and family samples

Most of the providers in the sample were employed in the partial hospitalization program (29 providers, or 49 percent) or the case management program (15 providers, or 25 percent) and were salaried. However, one quarter of the providers worked in the outpatient program (15 providers, or 25 percent) and were contract employees. Most providers were women (50 providers, or 85 percent), were white (52 providers, or 88 percent), and had graduated from college (24 providers, or 41 percent) or graduate school (20 providers, or 34 percent). Providers' disciplines included psychology (25 providers, or 42 percent), social work (nine providers, or 15 percent), and counseling (eight providers, or 14 percent).

Most family respondents (56 respondents, or 82 percent) had relatives receiving partial hospitalization services, 11 (16 percent) had relatives receiving case management services, and one (2 percent) had a relative receiving outpatient services. Most family respondents were women (52 respondents, or 77 percent), were white (63 respondents, or 93 percent), were parents (43 respondents, or 63 percent), and had some college or post-high school education (37 respondents, or 54 percent).

Most families' consumer relatives were men (41 respondents, or 60 percent) and were white (63 respondents, or 93 percent); these consumer relatives ranged in age from 18 to 67 years, with a median and mean age of 40 years. Families reported that the average length of time since their relative became ill was 20 years (median, 20 years) and that on average their consumer relatives had been receiving services for seven years (median, 5).

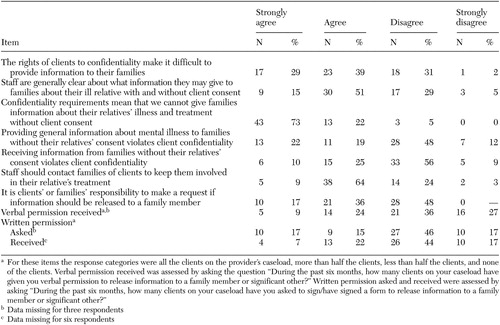

Perception of confidentiality as a barrier

Most providers who completed the survey (40 providers, or 68 percent) and participated in interviews (five providers, or 63 percent) believed that confidentiality policies made it difficult to provide information to families, as can be seen from Table 1. Providers who did not express that they had difficulties providing information to families described a more liberal interpretation of confidentiality policies—for example, "I don't request a consent to release (to families) … . The client is in agreement. They usually initiate all of this anyway."

Regression analysis, which controlled for race, gender, education, professional discipline, and program affiliation, showed that providers who believed that confidentiality made it difficult to provide information to families were more likely to have negative attitudes toward collaboration (F=2.15, df=6, 43, p=.02).

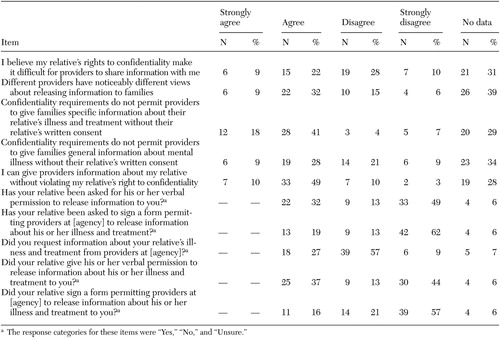

One-third of the family respondents believed that their relative's right to confidentiality made it difficult for providers to share information with them (21 families, or 31 percent) (Table 2). Twenty-eight family respondents (41 percent) agreed with the statement that different providers had noticeably different views about releasing information to families, 14 family members (21 percent) disagreed, and 26 family members (38 percent) did not respond to this item. Eight of 26 families who did not respond (12 percent) had no provider contact.

Confidential versus nonconfidential information

Most providers believed that staff were clear about the types of information that are confidential (39 providers, or 66 percent); however, 27 providers (46 percent) answered all three questions correctly. Most providers believed that confidentiality policies require clients' consent to provide information about their illness and treatment to their family (56 providers, or 95 percent)—for example, "[The family] wanted to talk to me, but I could not say anything specifically about the client. Even though he might have just passed them in the hall, I could not talk to them to let them know his status. They were really worried about him. But I could not say anything, that was kind of hard."

Although two of the eight providers who were interviewed indicated that they would not speak to a family at all without consumers' permission, more than half of the providers understood that providing general information about mental illness to families did not require consent (35 providers, or 59 percent), and approximately two-thirds understood that consent is not required to receive information from families (38 providers, or 64 percent).

Regression analysis indicated that providers in the partial hospitalization program were significantly more likely than case managers or outpatient staff to correctly identify the types of information that are confidential (F=1.30, df=6, 43, p=.04). Gender, race, education, professional discipline, and attitudes toward collaboration were not significant predictors of correct identification of the types of information that are confidential.

In contrast, most family respondents (40 respondents, or 59 percent) correctly believed that confidentiality prohibits providers from giving them information about their consumer relative without written consent but that they could give providers information. Many families incorrectly believed that confidentiality did not allow providers to give families general information about mental illness (25 families, or 37 percent).

Implementation of confidentiality

Although a majority of providers believed that clients and their families were responsible for requesting the release of information (31 providers, or 53 percent), they also indicated that they routinely initiated the release process (31 providers, or 53 percent). In addition, three-quarters of providers believed that staff should initiate family involvement (43 providers, or 73 percent). Qualitative data indicated that providers generally believed it was the consumer's responsibility to initiate the release process—for example, "All of our people are over 18 so they are treated as adults … . I usually leave it up to my client if they want to have their family involved."

Moreover, if providers initiated the consent process, this was done on a limited basis—for example, "I pretty much ask all of my clients at one point in time about their families, if they had contact, and if they said no, then pretty much, I drop it"

Few providers reported that they asked clients to sign a release form—ten providers (17 percent) reported doing so for all clients, and nine providers (15 percent) reported doing so for more than half of their clients—and most reported that few or no clients on their caseload had provided verbal permission or signed a release form. Interviews further revealed that whether providers asked for verbal permission or required written consent varied across providers. Providers who were interviewed suggested that consumers are generally willing to sign a consent form. However, providers explained that the likelihood of receiving consent was much lower if they introduced the form when the consumer was in the middle of a crisis or problem situation.

Similarly, most family respondents reported that they were unsure whether their consumer relative was asked to sign a consent form (42 respondents, or 62 percent) or had signed a consent form (39 respondents, or 57 percent). One-third (22 respondents, or 32 percent) reported that their relative was asked and had given verbal permission to the provider to release information to them. Most families reported that they had not requested information from providers (39 respondents, or 57 percent).

Discussion

The study results confirm assertions that providers interpret confidentiality policies conservatively (25,39) and believe that information cannot be provided to clients' families without consent. However, the results also indicate that providers are interpreting the law as being more restrictive than even the most conservative legal interpretation by believing that consent is needed to provide general information about mental illness or receive information from families.

There are two possible reasons that providers may be interpreting confidentiality policies so restrictively. First, providers may hold negative attitudes toward collaboration with families and, consequently, be hiding behind the veil of confidentiality to avoid communicating with families (24,40). Although the results of our study showed that providers with more negative attitudes toward collaboration were more likely to perceive confidentiality as a barrier to collaboration, no association was found between providers' attitudes toward collaboration and providers' implementation of confidentiality. Further research is needed to examine this relationship.

Second, providers' restrictive interpretation of confidentiality may be the result of informal agency guidelines. The desire to simplify the complexities of confidentiality policies may result in mental health programs' merely emphasizing the duty to protect client information. Study findings indicate that providers' understanding of confidentiality was significantly associated with program affiliation, suggesting that information and misinformation about confidentiality may be informally learned on the job.

Limitations

Generalizability of the results of this study may depend on whether mental health authorities have statutes, regulations, guidelines, or training in place and how thoroughly information is disseminated to providers. In addition, the study included only providers and families from community mental health programs. Further research is needed to ascertain whether differences exist in inpatient and outpatient settings. Other limitations of the study include the low rate of participation by outpatient providers, which administrators attributed to providers' status as contract employees, given that these providers are paid only for their time serving clients, have irregular schedules, and work in multiple offices. Although these providers received a complimentary lunch and $10 compensation for their time, additional incentives are necessary to engage them in research.

Implications

Although considerable harm may be done by inappropriately disclosing confidential information, harm may also result from inappropriately protecting information. Confidentiality policies maintain that it is for the consumer to decide whether to disclose or protect confidential treatment information (2,41). The results of this study suggest that current implementation of confidentiality policies does not seem to facilitate consumers' making these decisions when they have the capacity to do so.

These findings replicate those of a nationwide study that found that few consumers were asked for their oral or written permission (42). Providers who interpret confidentiality simply as "the duty to protect" without providing consumers with the choice to disclose are by default making the decision on behalf of the consumer that information should not be released. Lack of communication between providers and members of consumers' support networks may increase consumers' sense of isolation, prevent early intervention, and reinforce stigma by communicating the message that mental illness is "not something to talk about."

Many of the providers in our sample believed that consumers and their families would present a request if they wanted information released. However, few families made such requests. One explanation suggested by this study and by previous research is that many families do not expect confidentiality to be a barrier in communicating with providers and therefore do not feel the need to make specific requests for information, believing that all relevant information will automatically be shared with them (42). Given that providers' understanding and implementation of confidentiality policies varies by program affiliation, families and consumers are implicitly expected to follow different requirements depending on the services they are receiving. These findings call into question whether the expectation that families and consumers will initiate the consent process is realistic.

As presumed with the creation of the Federal Privacy Rule, the results of our study suggest that there is enormous variability in the implementation of confidentiality policies. The intention of the rule is to provide standards to alleviate that variability. However, the standards provided within the rule for releasing information to families are considerably more lenient than clarifications made within state statutes (31), and the current interpretation and implementation of confidentiality policies revealed in this study. Although 95 percent of the providers in this study indicated that information could not be released to families without consent, the rule states that "imposing a requirement for consent or written authorization in all cases for disclosures to individuals involved in a person's care would be unduly burdensome for all parties" (43).

It is unclear whether states with silent statutes, such as Pennsylvania, will decide to follow the more lenient Federal Privacy Rule or formalize more conservative guidelines that would preempt the federal standards. As mental health authorities work toward compliance with the rule, it will be important to develop consistent procedures for releasing information to the families of persons with mental illness.

Recommendations

On the basis of our findings, we make the following recommendations regarding the release of information to families of adults with mental illness. First, guidelines and procedures should clarify that it is the client's choice to protect or disclose confidential information. Second, written explanations of procedures for releasing information to families should be provided to consumers and their families. Third, given that consumers may be more likely to sign a consent form as a matter of routine rather than at the point of crisis, providers should initiate the consent process annually or semiannually. Fourth, agencies that require written consent for the release of information to families may need to modify their forms to ensure their appropriateness (44). Many agencies use inappropriate interagency release forms for families, which include time limits of 30, 60, or 90 days that require frequent updating for the sharing of information on an ongoing basis (33). Finally, guidelines and procedures should clarify the types of information that are confidential and emphasize that sharing general information about mental illness and receiving information from families does not violate confidentiality.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that providers' interpretation and implementation of confidentiality varies tremendously and seems to pose a barrier to collaboration between the provider, the consumer, and the consumer's family, which is currently recommended for the treatment of serious mental illness. Although providers believed that consent was needed for the release of information to families, few providers asked for or obtained client consent. As states and local agencies work toward compliance with the Federal Privacy Rule, guidelines and procedures are needed to address the variability in the implementation of confidentiality policies.

Acknowledgment

Research for this article was supported by grant 1-R03-MH-61031 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Marshall is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. Dr. Solomon is with the School of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Send correspondence to Dr. Marshall at 3700 Koppers Street, Suite 402, Baltimore, Maryland 21227 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Measures of 59 mental health care providers' attitudes toward the client confidentiality process

|

Table 2. Measures of attitudes toward the client confidentiality process among 68 families of mental health consumers

1. Gates J, Arons B: Privacy and Confidentiality in Mental Health Care. Baltimore, Md, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

2. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

3. Petrila J, Sadoff R: Confidentiality and the family as caregiver. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:136–139, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Weiner B: Provider-patient relations: confidentiality and liability, in The Mentally Disabled and the Law. Edited by Brakel E. New York, American Bar Foundation, 1985Google Scholar

5. Beeler J, Rosenthal A, Cohler B: Patterns of family caregiving and support provided to older psychiatric patients in long-term care. Psychiatric Services 50:1222–1224, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Guarnaccia P: Multicultural experiences in family caregiving: a study of African American, European American, and Hispanic American families. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 77:45–61, 1998Google Scholar

7. Goldman H: Mental illness and family burden: a public health perspective. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:557–559, 1982Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Lehman A, Steinwachs D: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–32, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hatfield A, Lefley H: Families of the Mentally Ill: Coping and Adaptation. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

10. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364–1370, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Anderson C, Reiss D, Hogarty G: Schizophrenia and the Family. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

12. Falloon I, Boyd J, McGill C: Family Care of Schizophrenia. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

13. Leff J, Kuipers L, Berkowitz R: Controlled trial of social interventions in the families of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:121–134, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(4 suppl):1–63, 1997Google Scholar

15. Dixon L, Lehman A: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631–643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Treatment of schizophrenia: the Expert Consensus Panel for Schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):3–58, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

17. Family Interventions Work: Putting the Research Findings Into Practice. Presented at the World Schizophrenia Fellowship, Christchurch, New Zealand, Sept 4–5, 1997Google Scholar

18. Dixon L, McFarlene W, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Link, Google Scholar

19. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233–238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

20. Biegel D, Song L, Milligan S: A comparative analysis of family caregivers' perceived relationships with mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services 46:477–482, 1995Link, Google Scholar

21. DiRienzo-Callahan C: Family caregivers and confidentiality. Psychiatric Services 49:244–245, 1998Link, Google Scholar

22. Furlong M, Leggatt M: Reconciling the patient's right to confidentiality and the family's need to know. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:614–622, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Krauss J: Sorry, that's confidential. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6:255–256, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Leazenby L: Confidentiality as a barrier to treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:1467–1468, 1997Link, Google Scholar

25. Lefley H: Families' perspectives on confidentiality, in Privacy and Confidentiality in Mental Health Care. Edited by Gates J, Arons B. Baltimore, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

26. Marsh D: Confidentiality and the rights of families: resolving potential conflicts. Pennsylvania Psychologist Jan 1995, pp 1–3Google Scholar

27. Ryan C: Comment on reconciling the patient's right to confidentiality and the family's need to know. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:429–431, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Zipple A, Langle S, Spaniol L: Client confidentiality and the family's need to know: strategies for resolving the conflict. Community Mental Health Journal 26:533–545, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gellman R: Will technology help or hurt in the struggle for health privacy? Atlanta, Carter Center, 1997Google Scholar

30. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act: Pub L no 104–191, 110 Stat 1936, 1996Google Scholar

31. Petrila J: State mental health confidentiality law provisions, in Privacy and Confidentiality in Mental Health Care. Edited by Gates J, Arons B. Baltimore, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

32. Pennsylvania Statutes 50 Pa Cons Stat §§ 7103 and 7111Google Scholar

33. Bogart T, Solomon P: Collaborative procedures to share treatment information among mental health care providers, consumers, and families. Psychiatric Services 50:1321–1325, 1999Link, Google Scholar

34. Hatfield A: Family Education in Mental Illness. New York, Guilford, 1990Google Scholar

35. Lefley H: An overview of family-professional relationships, in New Directions in the Psychological Treatment of Serious Mental Illness. Edited by Marsh D. Westport, Conn, Praeger, 1994Google Scholar

36. Tessler R, Gamache G, Fisher G: Patterns of contact of patients' families with mental health professionals and attitudes toward professionals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:929–935, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

37. Rubin A, Cardenas J, Warren K, et al: Outdated practitioner views about family culpability and severe mental disorders. Social Work 43:413–422, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

38. SPSS User's Guide, version 11.0. Chicago, SPSS, Inc, 2001Google Scholar

39. Bernheim K: Patient Confidentiality and You. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1993Google Scholar

40. Epstein E, Oram S: Mental health records: the protective veil of confidentiality. Maine Bar Journal 11:162–166, 1996Google Scholar

41. Campbell J: The consumer perspective, in Privacy and Confidentiality in Mental Health Care. Edited by Gates J, Arons B. Baltimore, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

42. Marshall T, Solomon P: Releasing information to families of persons with severe mental illness: a survey of NAMI members. Psychiatric Services 51:1006–1011, 2000Link, Google Scholar

43. Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

44. Solomon P, Marshall T, Mannion E, et al: Social workers as consumer and family consultants, in Social Work Practice in Mental Health. Edited by Bentley K. Pacific Grove, Calif, Brooks/Cole, 2002Google Scholar