History and Measurement of Continuity of Care in Mental Health Services and Evidence of Its Role in Outcomes

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The objective of this study was to provide a brief history of the concept of continuity of care, to update evidence of its association with patient outcomes, and to identify optimal characteristics of a continuity-of-care instrument. METHODS: Articles describing recent (1990 to 2002) empirical work on continuity of care were drawn from a broader set of 305 articles about continuity of care that were obtained from a systematic literature search. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: The literature shows that ideas about continuity of care have changed in concert with general service delivery changes over the decades. Since 1997, only eight studies have used operationally defined measures either to describe continuity of care in mental health services or to examine the association of continuity of care with outcomes for adults with severe and persistent mental illness. Only three groups of researchers have published articles on development of continuity-of-care measures. CONCLUSIONS: There is little evidence that continuity of care results in better client outcomes, which may be primarily attributable to the underdevelopment of measures. Measurement of continuity of care must become more sophisticated before key questions about the association of continuity of care with outcomes can be examined and before the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve continuity of care can be rigorously evaluated.

In mental health services, continuity of care is "a process involving the orderly, uninterrupted movement of patients among the diverse elements of the service delivery system" (1). For more than 40 years continuity of care has been considered to be crucial in the management of persons with severe and persistent mental illness. The need for better understanding of the phenomenon of continuity of care has long been recognized (1) and has intensified recently in response to the restructuring of services. Continuity of care is now seen as a core value in care delivery (2), a key indicator in health care performance measurement (3,4,5), and a priority for research (6).

However, anecdotes about service fragmentation and discontinuity persist among practitioners, and impressions that the concept of continuity of care is insufficiently operationalized to rigorously test whether it improves outcomes persist among researchers. In an age of evidence-based practice, demonstration of such an association will be crucial to the future of community psychiatry. The objectives of this study were to provide a brief history of the concept of continuity of care, to update evidence of its association with outcomes and progress on its measurement, and to identify optimal characteristics of a continuity-of-care instrument.

Methods

A systematic, validated literature search was undertaken for English-language articles about continuity of care for the years 1970 to mid-2002. The databases MEDLINE, HealthSTAR, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and PsycINFO were searched by using the term "continuity of patient care" and close variants as appropriate for each database. A total of 1,673 articles were retrieved. After duplicates were removed, independent judgments of three of the authors (CEA, AJ, and CTW), followed by consensus decisions, were used to select the articles that were most relevant to mental health services only (N=360) and then to select articles considered to be relevant according to an a priori operational definition (N=305) (available from the authors). A second search, conducted by an expert librarian for validation, showed that 97 percent of articles deemed to be relevant were captured by the initial search.

From the 305 articles on mental health services that met the multirater relevancy criteria, definitions were extracted by trained content analysts. Key historical studies and articles containing empirical information about measurement and effects of continuity of care were reviewed. For the review of the effects of continuity of care, articles were included only if they explicitly defined continuity of care among multiple services and examined the relationship of continuity of care with outcomes among adults with severe and persistent mental illness. The review was part of a larger measure-development study that was approved by the conjoint health research ethics board at the University of Calgary.

Results and discussion

History of the concept

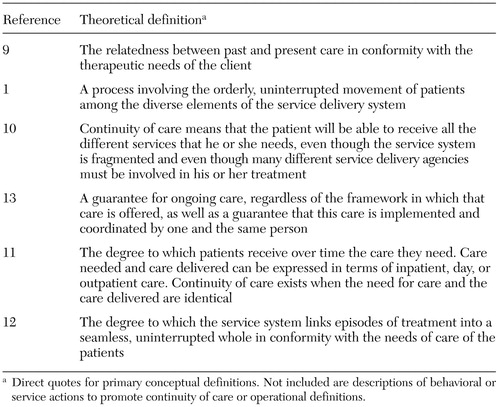

The origin of continuity of care as a service delivery principle can be traced to the early 1960s in North America (7,8). Since that time many theoretical and conceptual definitions have arisen in the literature (Table 1) (1,9,10,11,12,13). The first attempt to operationalize continuity of care was reported in 1967 (14). The institutional care context resulted in a definition focused on readmissions to and transfers between psychiatric facilities (14). Subsequent operational work has also reflected the service delivery context. During deinstitutionalization the concept shifted to include follow-through on community contacts after referral or discharge and aspects of community-based care—client movement in response to need, stability of the client-caregiver relationship, communication among providers, and efforts to retrieve clients lost to treatment (9,15,16,17).

In the late 1970s the rise of case management approaches such as assertive community treatment had enormous influence on ideas about continuity of care (18,19). Such interventions were designed fundamentally to improve continuity of care. As a result, the continuity-of-care concept of that period is almost indistinguishable from the interventions themselves, and evidence of the effectiveness of assertive community treatment continues to be taken, tautologically, as evidence of the effectiveness of continuity of care rather than as a phenomenon that can be measured and tested independent of a particular program model.

Despite the growth of general hospital psychiatry and the service continuum in the 1980s, there was little further development of continuity-of-care measures. Operationalization was still considered to be difficult, although some indicators were tested and calls were made for research on the effects of continuity of care (20). The theory of continuity of care as a multidimensional concept was also advanced during that period by Bachrach and others (1,10,20,21), with a shift in emphasis toward team rather than individual provider-based care as well as inclusion of the perspective of the patient on continuity of care.

The 1990s heralded major restructuring of health care systems in most developed countries through regionalization and integration of services. In this context, continuity of care was seen as a potential measure of system-level reform. Thus the idea of continuity of care as "a planned coordination of the movement of a patient along the various components of the care delivery system" was added to the earlier concept of "continuity by the same caregiver (or group of caregivers) according to the patient's needs" (22).

The science of continuity of care to the mid-1990s

In a comprehensive review published in 1997, Johnson and colleagues (23) summarized the "state of the science" of continuity of care measurement and application through 1994. Highlights of the work of that period include increasing recognition that the postdischarge connection measures of continuity of care were too focused on the acute care event (24) and that longitudinal changes in continuity of care could be characterized (25). However, Johnson and colleagues concluded that continuity-of-care measurement was still in its infancy and that the evidence of associations with a variety of outcomes was still mixed at best.

The current descriptive literature

We found three new descriptive studies in which continuity-of-care measures were defined and applied. These studies were by Farrell and colleagues (26), Sytema and colleagues (11), and Saarento and colleagues (12). Farrell and colleagues examined continuity of care retrospectively for 4,930 adult patient discharges from eight psychiatric hospitals in Virginia in 1992. Personnel from 14 mental health centers rated aspects of continuity of care—a record of discharge, notification of the discharge, and predischarge staff contact—from chart information, and composite scores were produced. Continuity of care was found to be poorer in urban areas, among patients with substance abuse, and among African Americans. Ceiling effects on the continuity-of-care index were noted—that is, most items were scored positively—and it was concluded that "future work would benefit from operational measures of continuity that conform better to normal distributions" (26).

Sytema and colleagues (11) compared continuity of care by using administrative data for persons with psychotic disorders who had received care during a two-year period in a region in Italy (N=58) and a region in the Netherlands (N=340). Continuity of care was defined as postdischarge contact and the combination of inpatient, day, and outpatient care received. A higher proportion of patients received community care and had a combination of care in the Italian region (72 percent and 62 percent, respectively) than in the region in the Netherlands (55 percent and 45 percent, respectively). The investigators found that measures based on administrative data had important deficiencies, including the inability to interpret continuity of care according to need. They also stressed that "a longitudinal study of [continuity of care]…requires record linkage of care delivery data…and information about need, not only at a specific time but also about transitions in need in time."

The Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry (12) compared continuity of care in seven areas of four European countries. The study followed one-year cohorts of patients with psychosis after the first psychiatric service event (N=570) and defined continuity of care as postdischarge contact. Large differences were found among the countries; the proportions of patients with continuity of care ranged from 34 percent to 71 percent. Long lag times to contact were also found. Significant predictors of continuity of care were predischarge contact, duration of hospitalization, and location of aftercare services. The authors concluded that "further studies should include outcome measures, cost analyses, and information about the local health care system and its functioning as a whole."

These three articles might be characterized as the descriptive epidemiology of continuity of care. They have advanced the breadth of study settings and included analysis of continuity-of-care predictors, but surprisingly the operational definitions of continuity of care have remained relatively unidimensional and discharge based. The reasons cited for this situation usually center on lack of availability of more comprehensive measures and feasibility of application in large system- level studies.

The current analytic literature on continuity of care

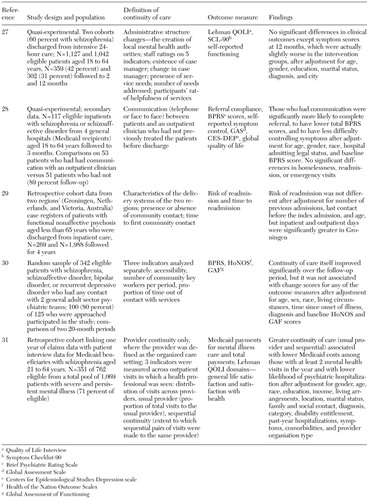

We found five articles that examined the association between continuity of care and patient outcomes (27,28,29,30,31), summarized in Table 2. It is apparent that the evidence remains limited. Effects have been shown for symptom control and length of stay on readmission only. The study populations have been reasonably comparable in terms of age and diagnosis, and the samples are generally of adequate size to show reasonable effect sizes, although specific calculations of sample size are not reported.

However, there is virtually no consistency in the way that continuity of care has been measured or in the choice of outcome measures. Important outcomes have been examined—that is, symptoms, functioning, and quality of life—but with little consistency in the instruments used. More emphasis is also needed on selection of outcomes that are logically linked with intervention activities ranging from medication and provider utilization through activities of daily living and community tenure. Although multivariate methods were used to adjust for potential confounders, there is little similarity in the number and type of variables used for adjustment. It would appear that currently the greatest need is for more standard and sophisticated measurement of both continuity of care and outcomes.

Summary of the literature on instrument development

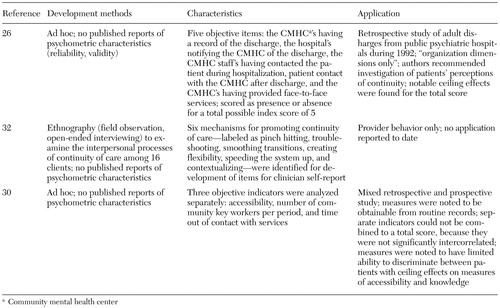

Little progress has been made in the development of continuity-of-care measures. Only three groups of researchers have undertaken methodologic work on more comprehensive instruments for the measurement of continuity of care (26,30,32) (Table 3). Instrument development remains largely ad hoc, and no psychometric characteristics of instruments have been published. Only one study (32) incorporated the patient's perspective, but in that case the instrument was relevant only to the relationship component of continuity of care (provider behavior), which represents a limitation in the utility of the study for examining system-level changes. Moreover, ceiling effects are common, and there is minimal broader application of these measures beyond the investigator's developmental studies.

Recommendations for instrument development

There is still much room for improvement in the development of continuity-of-care instruments. Consensus exists that continuity of care is a multidimensional concept, which should be reflected in instrument development. The need for measures with scales that produce good statistical distributions and have established psychometric properties is apparent. The inclusion of the patient and family perspective on and experience of continuity of care is a frequent recommendation in the literature, but the validity of subjective measures is unknown, and objective development of measures should continue. Ideally a continuity-of-care instrument should have utility across service interfaces at multiple levels of the health care delivery system. Identification of the conceptual boundaries between continuity of care and other service measures—for example, quality of care, access, and satisfaction—is an untouched area of research.

Conclusions

Continuity of care has been, by considerable consensus, an important aspect of the process of mental health service delivery since the 1960s. Theoretical and conceptual writing on continuity of care is extensive, yet measurement of continuity of care remains underdeveloped. The impact of specific treatment modalities, such as assertive community treatment and other types of case management, cannot be directly inferred as evidence of the effectiveness of continuity of care as a general phenomenon.

Because continuity of care is now a priority for research, the imperative for better measures is even greater. Continuity of care needs to be examined as a process that occurs at the interfaces among multiple services and providers in complex delivery systems, and its relationship with outcomes needs to be clarified before interventions can be designed and tested that are intended to improve continuity of care itself as well as patient outcomes. In an era of evidence-based practice, progress in this task will be critical to the future of community-based psychiatry.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant RC2-2709 from the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and cosponsored by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, the Alberta Mental Health Board, the Institute of Health Economics, and an unrestricted grant from Eli Lilly (Canada) Inc.

Dr. Adair and Dr. Mitton are affiliated with the department of community health sciences of the University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Drive, N.W., Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 4N1 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Adair is also with the university's department of psychiatry and with the Alberta Mental Health Board in Calgary, with which Dr. McDougall is affiliated. Ms. Beckie is with the Alberta Mental Health Board. Dr. Joyce, Dr. Gordon, and Dr. Costigan are with the department of psychiatry of the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Wild is with the Center for Health Promotion Studies of the University of Alberta. Part of this paper was presented at the Congress of Epidemiology held June 13 to 16, 2001, in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Theoretical definitions of continuity of care in the mental health services literature

|

Table 2. Studies published since 1994 of the association between continuity of care and outcomes among adults with severe and persistent mental illness

|

Table 3. Current continuity-of-care instrument development studies

1. Bachrach L: Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:1449–1456, 1981Link, Google Scholar

2. Tansella M, Thornicroft G: A conceptual framework for mental health services: the matrix model. Psychological Medicine 28:503–508, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Millar J: Experience in the field: assessing quality of health care reform in Canada. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 22:589–592, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. O'Kane ME: HEDIS and managed behavioral healthcare. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 6:61–62, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hermann RC: Quality measures for mental health care: results from a National Inventory. Medical Care Research and Review 57:136–154, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fulop N: Commissioned programmes: update: continuity of care. SDO News, no 2, p3, 2001 [newsletter of the National Health Service Service Delivery Organization R&D Programme]Google Scholar

7. Community Mental Health Centers Act, PL 88–164, 1964Google Scholar

8. Tyhurst JS, Chalke FCR, Lawson FS, et al: More for the Mind. Toronto, Canadian Mental Health Association, 1963Google Scholar

9. Bass RD, Windle C: Continuity of care: an approach to measurement. American Journal of Psychiatry 129:110–115, 1972Link, Google Scholar

10. Bachrach LL: Continuity of care. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 35:63–73, 1987Google Scholar

11. Sytema S, Micciolo R, Tansella M: Continuity of care for patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a comparative South-Verona and Groningen case-register study. Psychological Medicine 27:1355–1362, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Saarento O, Oiesvold T, Sytema S, et al: The Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry: continuity of care related to characteristics of the psychiatric services and the patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:521–527, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cohen D, Sanders H: Day-program-based treatment in the Amsterdam city center. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 41:120–131, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pugh TF, MacMahon B: Measurement of discontinuity of psychiatric inpatient care. Public Health Reports 82:533–538, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wolkon GH: Characteristics of clients and continuity of care into the community. Community Mental Health Journal 6:215–211, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Bass RD, Windle C: A preliminary attempt to measure continuity of care in a community mental health centre. Community Mental Health Journal 9:53–62, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Tessler R, Mason J: Continuity of care in the delivery of mental health services. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:1297–1301, 1979Link, Google Scholar

18. Test MA: Continuity of care in community treatment. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 2:15–23, 1979Google Scholar

19. Test MA, Stein LI: Practical guidelines for the community treatment of markedly impaired patients. Community Mental Health Journal 36:47–60, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Tessler RC, Willis G, Gubman GD: Defining and measuring continuity of care. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 10:27–38, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Bachrach LL: Continuity of care: a context for case management, in Case Management for Mentally Ill Patients: Theory and Practice: Chronic Mental Illness, vol 1. Edited by Harris M, Bergman HC. Langhorne, Pa, Harwood Academic Publishers/Gordon & Breach Science Publishers, 1993Google Scholar

22. Perris C, Rodhe K, Palm A, et al: Fully integrated in- and outpatient services in a psychiatric sector: implementation of a new model for the care of psychiatric patients favoring continuity of care, in Cognitive Therapy: Applications in Psychiatric and Medical Settings. Edited by Freeman A, Greenwood V. New York, Human Sciences Press, 1987Google Scholar

23. Johnson S, Prosser D, Bindman J, et al: Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: concepts and measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:137–142, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

24. Barbato A, Terzian E, Saraceno B, et al: Patterns of aftercare for psychiatric patients discharged after short inpatient treatment: an Italian collaborative study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:46–52, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Shern DL: Client outcomes: II. longitudinal client data from the Colorado Treatment Outcome Study. Milbank Quarterly 72:123–148, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Farrell S, Koch J, Blank M: Rural and urban differences in continuity of care after state hospital discharge. Psychiatric Services 47:652–654, 1996Link, Google Scholar

27. Lehman A, Postrado L, Roth D, et al: Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program on chronic mental illness. Milbank Quarterly 72:105–122, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Boyer CA, et al: Linking inpatients with schizophrenia to outpatient care. Psychiatric Services 49:911–917, 1998Link, Google Scholar

29. Sytema S, Burgess P: Continuity of care and readmission in two service systems: a comparative Victorian and Groningen case-register study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:212–219, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bindman J, Johnson S, Szmukler G, et al: Continuity of care and clinical outcome: a prospective cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:242–247, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Chien C, Steinwachs DM, Lehman AF, et al: Provider continuity and outcomes of care for persons with schizophrenia. Mental Health Services Research 2:201–211, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Ware N, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, et al: An ethnographic study of the meaning of continuity of care in mental health services. Psychiatric Services 50:395–400, 1999Link, Google Scholar