Racial Differences in the Diagnosis of Dementia and in Its Effects on the Use and Costs of Health Care Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined differences in the prevalence of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries by race and gender as well as racial differences in the effects of dementia on the use and costs of health care services. METHODS: Data from a 5 percent random sample of Medicare beneficiaries in the state of Tennessee who filed claims between 1991 and 1993 (N=33,680) were analyzed. Dementia was assessed on the basis of ICD-9 codes in the billing records of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), along with information on gender, race, comorbid psychiatric conditions, use of health services, and the actual amounts paid by HCFA. Patients with dementia related to Alzheimer's disease were excluded. RESULTS: Diagnoses of dementia were significantly more prevalent among African-American beneficiaries than among white beneficiaries (5 percent compared with 3.9 percent). Persons with dementia had higher rates of health service use, particularly for inpatient care, and African-American persons with dementia had the highest levels of service use. Health care costs were also significantly higher for African Americans with a diagnosis of dementia. Among patients of either race, costs were substantially higher among those with comorbid psychiatric conditions. CONCLUSIONS: Racial differences in the prevalence of dementia are clearly evident. Race also plays a role in the effects of dementia on the use and costs of health services, with higher rates of expensive inpatient care among African Americans. Racial differences in both the prevalence and costs of dementia produce a considerable burden on the health care system. Addressing racial disparities in the prevalence of dementia would result in substantial cost savings.

The prevalence of dementia among people aged 65 years or older in the United States has been estimated to be between 5 percent and 10 percent. However, estimates vary widely across populations in different countries and in different clinical and institutional settings (1,2,3). Researchers have singled out the importance of both race and gender as predictors of dementia.

Findings on racial variations in dementia are somewhat equivocal. Although race and dementia were unrelated in one study (4), other studies have reported higher frequencies of dementia among nonwhite persons (3,5,6,7,8,9). A number of studies suggest that disproportionately high rates of dementia among African-American persons are due, in part, to a higher prevalence of both hypertension and stroke among African-American elderly persons (7,10,11,12,13). There is also evidence that women have higher rates of dementia than men, largely because women live longer (14,15).

Sampling issues limit our current understanding of racial differences in the prevalence of dementia in the United States. Most studies have examined nursing home samples. Such samples are problematic because African Americans are underrepresented in nursing home studies, and African Americans who are living in nursing homes are not necessarily representative of other African Americans. African Americans have lower incomes and less access to formal care settings such as nursing homes, partly because Medicare does not pay for nursing home care. Furthermore, high levels of social support in African-American communities—for example, through family and churches—may enable African Americans with dementia to remain in the community (9,16). And because African Americans are more likely to die from comorbid conditions associated with dementia (17,18), it is likely that the disease will not progress to the point that institutionalization is needed.

The co-occurrence of depression and dementia has been demonstrated in a number of studies (19,20,21). Dementia that co-occurs with depression was found to be more prevalent among homebound elderly persons who were referred for psychiatric services, and dementia alone was found to be more common among inpatients who were admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit (22,23). A study of neuropsychiatric symptoms among outpatients with dementia showed a stronger association between dementia and psychosis among African-American patients, whereas the co-occurrence of dementia and depression was more common among white patients (24,25).

Our study addressed two key questions. First, are there racial differences in the prevalence of non-Alzheimer's dementia? Second, are there racial differences in the effect of dementia on the use and costs of health care services? Answering these two questions will enable us to assess both the human and the economic impact of racial disparities in dementia and to estimate the cost of these racial disparities for Medicare.

Methods

Sample

We examined a 5 percent random sample (N=33,688) of white (N=30,089) and African-American (N=3,599) Medicare beneficiaries in Tennessee who filed claims from 1991 to 1993. The sample included all elderly persons for whom a claim had been filed if the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) had been charged for any component of the costs. Thus all inpatient and outpatient hospitalizations for persons over the age of 65 years under Medicare Part A and all physician and other health care costs for those enrolled under Medicare Part B were included. Billing data from the files of physicians, hospitals, nursing homes, and hospices were combined to create a master file for both diagnoses and costs.

Some elderly people do not enroll in Medicare Part B, either because they cannot afford it (veterans in this category would have all costs paid for by the Department of Veterans Affairs) or because they have private insurance or other coverage that pays for medical expenses. Because this sample included only persons who had seen a physician or sought medical services in the three-year period, the rates may be inflated. Yet few people over the age of 65 fail to have a single visit to a health service provider in a three-year period. Eleven percent of the sample was African American, compared with 12 percent in the 1990 Census for Tennessee. Thus although African Americans are somewhat less likely to visit a physician or seek care, our sample largely reflected the racial composition of the elderly population of the state. Among the beneficiaries in the sample, 61 percent were women, and the average age was 75 years.

Measures

Dementia was defined as an ICD-9 diagnosis indicating any type of vascular, progressive dementia. Specific ICD-9 codes included 290.10-13, 290.20-21, 290.3, and 290.40-43, although we excluded dementia associated with Alzheimer's disease (ICD-9 code 331.0), which reduces the overall rates. Comorbid psychiatric illness was defined as more than one mental health diagnosis in the period covered. Psychiatric diagnoses, including substance use disorders, were identified on the basis of ICD-9 codes provided by physicians in the billing data. It is likely that comorbid illness was underestimated, given that multiple diagnoses are sometimes not coded.

We investigated racial and gender differences in the number of inpatient hospital days, outpatient visits, and physician visits and in whether the person visited an emergency department during the three-year period. We also examined total costs, mental health care costs, non-mental health care costs, inpatient care costs, outpatient care costs, costs from physician visits, and other health care costs. All costs were calculated on the basis of the actual reimbursement data and are expressed in 1991-1993 dollars. Our analyses focused on costs paid by HCFA rather than on bills submitted by providers.

Analyses

We first examined three-year prevalence rates for diagnoses of dementia and comorbid psychiatric illness by race and gender. Next, we investigated racial differences in the use and costs of health services by dementia status. We also broke down costs by comorbid psychiatric illness. We used t tests to determine the statistical significance of differences.

Results

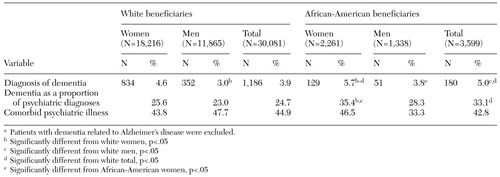

Prevalence of dementia by race and gender

During the three-year study period, 4.1 percent of the beneficiaries in the sample had a diagnosis of dementia, and 15.8 percent had some kind of psychiatric diagnosis. Variations in the prevalence of dementia diagnoses by race and gender can be seen in Table 1. The prevalence of dementia was higher among African-American women than among white women or among men of either race. White women had significantly higher rates of dementia than white men, but the difference between white women and African-American men was not significant.

Overall, a significant difference in the prevalence of dementia was noted between whites and African Americans (3.9 percent compared with 5 percent); that is, an African-American person over the age of 65 was 28 percent more likely than a white person to have a diagnosis of dementia. Extrapolation of this finding to the population of Tennessee suggests that the racial difference in the prevalence of dementia are associated with 763 more cases of dementia among African Americans than among whites.

Among elderly persons with a psychiatric diagnosis of any kind, dementia was diagnosed among more than 25 percent. Among Medicare beneficiaries with comorbid psychiatric illness, African Americans were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia. Dementia diagnoses were most prevalent among African-American women—35 percent of all elderly African-American women with any psychiatric diagnosis had a diagnosis of some type of dementia, significantly higher than among white men or women (Table 1).

Elderly people with dementia often have other psychiatric diagnoses. Around 45 percent of respondents who had dementia—white or African American—had comorbid psychiatric illness. Rates of comorbid psychiatric illness did not vary significantly by race or gender. Although African-American men had much lower rates of comorbid psychiatric illness, this difference was not statistically significant because of the relatively small number of African-American men with dementia in the sample (N=51).

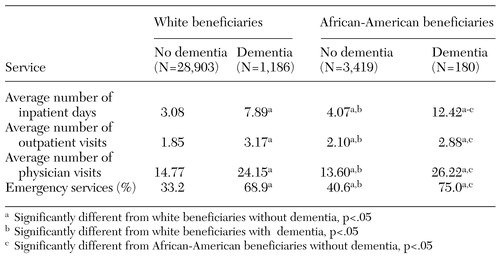

Race, dementia, and service use

Racial differences in health service use by dementia status are illustrated in Table 2. African Americans with dementia spent significantly more days in the hospital than their white counterparts (about 4.5 days more). African Americans with a diagnosis of dementia had more than three times as many hospitalization days as those without dementia. Elderly persons with dementia also had significantly more outpatient visits and physician visits as well as greater use of emergency services. However, we did not find significant racial differences in other types of health service use by dementia status.

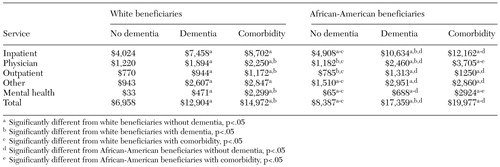

Race, comorbid psychiatric illness, and health care costs

Health care costs were significantly higher for elderly persons with dementia, and costs for African Americans were significantly higher, as can be seen in Table 3. The average cost for white persons without dementia was less than $7,000, compared with $12,904 for those with dementia. The average health care cost for African Americans without dementia was $8,400, significantly more than the costs for whites. For African Americans with dementia, the average cost was more than $17,000, significantly higher than for African Americans who did not have a diagnosis of dementia and significantly higher than for whites who had dementia. Comorbid psychiatric illness was associated with significantly higher health care costs for both whites and African Americans. Furthermore, the breakdown of types of costs showed that this difference was not simply a function of higher costs of psychiatric care for persons with multiple diagnoses. Higher costs for patients with dementia, particularly African Americans, were partly attributable to higher rates of use of inpatient and emergency services.

Discussion and conclusions

This study provided estimates of the prevalence of dementia among persons over the age of 65 years on the basis of a large, representative sample. Because all Americans over the age of 65 years are enrolled in Medicare, and because private insurance companies will not reimburse costs until Medicare has been billed, these data are uniquely suited to estimating the prevalence of dementia. Other studies have been limited to assessing the prevalence in clinical populations.

We found important racial and gender differences in the prevalence of dementia. Furthermore, the results have highlighted the enormous impact of dementia on the use and costs of health care services. Patients with dementia require a great deal of inpatient care, outpatient care, physician treatment, and emergency assistance, and we found that dementia had a greater impact on the use of inpatient services among African Americans with dementia. Furthermore, a diagnosis of dementia had a substantial effect on the costs of care—Medicare paid more than twice as much to cover the health care costs of elderly persons with a diagnosis of dementia as it did to cover those without dementia.

When the human and economic costs associated with racial disparities in the diagnosis of dementia are quantified, the importance of our findings is even more apparent. As noted above, our estimates suggest that if there were no racial differences in the prevalence of dementia, 763 fewer African Americans in Tennessee would have had a diagnosis of dementia. This number represents a substantial number of excess cases given the burden of dementia on patients and their families. Furthermore, Tennessee is typical of other states in the South, and we expect that these differences in the prevalence of dementia are generalizable to the region if not beyond the region. Racial differences in the costs associated with dementia are substantial; the average Medicare costs for the African-American patients with dementia in this study were $4,645 higher than those for white patients.

The human and economic costs associated with racial disparities in dementia underscore the enormity of the problem of racial disparities. If the 763 excess cases of dementia were eliminated, Medicare would save about $14 million, even if disparities in costs remained. If the costs associated with dementia were equal for whites and African Americans, Medicare would have saved more than $16 million in Tennessee during the three-year study period. Together, disparities in the prevalence of dementia and disparities in health care costs were responsible for nearly $21 million in excess expenditure. Less than 6 percent of elderly African Americans in the South live in Tennessee. Thus even if our findings are generalizable only to the South, the total cost of racial disparities is enormous.

Although physicians' sociocultural biases may have been a factor in the higher prevalence of dementia among African-American women in this study, this finding is in keeping with previous observations. Women live longer than men, and age is an important risk factor for dementia. In addition, postmenopausal women who are not taking hormone-replacement therapy—as is likely in lower-income populations and among African-American women—have a higher risk of developing dementia (26).

More generally, stroke may also play a role in the higher prevalence of dementia among African Americans. Stroke is an independent predictor of vascular dementia as well as a comorbid factor in Alzheimer's disease, the two leading causes of dementia (27,28). Other risk factors for vascular dementia that may be more prevalent among African Americans include hypertension, smoking, and cardiac disease (11,12,13,29). Future studies should use longitudinal tracking to identify the causal relationship between hypertension, stroke, and dementia. Assessing the magnitude of these effects would be of great interest given the development of new drugs that could be used to proactively combat dementia among persons with an elevated risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants 20-C-90705/4 and 20-P-90889/4 from the Health Care Financing Administration, grant 2S06-GM-08092-24 from the National Institutes of Health, and grant R24-MH-59748-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Husaini.

Dr. Husaini and Mr. Cain are affiliated with the Center for Health Research at Tennessee State University, Box 9580, Nashville, Tennessee 37209 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sherkat is with the department of sociology of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. Dr. Holzer is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. Dr. Moonis is with University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care in Worcester. Dr. Levine is with the School of Medicine at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. A version of this study was presented at the annual meeting of American Health Services Research, held June 25-27, 2000, in Los Angeles.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of dementia among elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Tennessee, by race and gendera

a Patients with dementia related to Alzheimer's disease were excluded.

|

Table 2. Health service use among elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Tennessee, by race and dementia status

|

Table 3. Average health care costs, in 1991-1993 dollars, for elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Tennessee, by race, dementia status, and comorbid psychiatric illness

1. Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD: The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatric Services 50:1158-1166, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Hendrie HC: Epidemiology of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 6(suppl 1):S3-S18, 1998Google Scholar

3. Perkins P, Annegers JF, Doody RS, et al: Incidence and prevalence of dementia in a multiethnic cohort of municipal retirees. Neurology 49:44-50, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fillenbaum GG, Heyman A, Huber MS, et al: The prevalence and 3-year incidence of dementia in older black and white community residents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51:587-595, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Folstein MF, Bassett SS, Anthony JC, et al: Dementia: case ascertainment in a community survey. Journal of Gerontology 46:M132-M138, 1991Google Scholar

6. Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R, et al: Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:481-493, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Heyman A, Fillenbaum G, Prosnitz B, et al: Estimated prevalence of dementia among elderly black and white community residents. Archives of Neurology 48:594-598, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Shadlen MF, Larson EB, Gibbons L, et al: Alzheimer's disease symptom severity in blacks and whites. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 47:482-486, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weintraub D, Raskin A, Ruskin PE, et al: Racial differences in the prevalence of dementia among patients admitted to nursing homes. Psychiatric Services 51:1259-1264, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Guo Z, Viitanen M, Winblad B, et al: Low blood pressure and incidence of dementia in a very old sample: dependent on initial cognition. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 47:723-726, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Baker FM: Dementing illness in African American populations: evaluation and management for the primary physician. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 24:73-91, 1991Google Scholar

12. Baker FM: Ethnic minority elders: a mental health research agenda. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:337-338, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Baker FM: Psychiatric treatment of older African Americans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:32-37, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al: Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: the impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham study. Neurology 49:1498-1504, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, et al: The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:809-815, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Taylor RJ, Ellison CG, Chatters LM, et al: Mental health services in faith communities: the role of clergy in black churches. Social Work 45:73-87, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Barnett E, Armstrong DL, Casper ML: Social class and premature mortality among men: a method for state-based surveillance. American Journal of Public Health 87:1521-1525, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Gornick ME: Disparities in Medicare services: potential causes, plausible explanations, and recommendations. Minority Health Today 2:17-30, 2001Google Scholar

19. Class CA, Unverzagt FW, Gao S, et al: Psychiatric disorders in African American nursing home residents. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:677-681, 1996Link, Google Scholar

20. Cohen CI, Hyland K, Magai C: Interracial and intraracial differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms, sociodemography, and treatment among nursing home patients with dementia. Gerontologist 38:353-361, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Alexopoulos GS, Young RC, Meyers BS: Geriatric depression: age of onset and dementia. Biological Psychiatry 34:141-145, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Pasternak R, Rosenweig A, Booth B, et al: Morbidity of homebound versus inpatient elderly psychiatric patients. International Psychogeriatrics 10:117-125, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cohen CI, Magai C: Racial differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among dementia outpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 7:57-63, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Gore R, et al: Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in nondemented elderly women: a prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:425-430, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Meyers BS: Depression and dementia: comorbidities, identification, and treatment. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 11:201-205, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kawas C, Resnick S, Morrison A, et al: A prospective study of estrogen replacement therapy and the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Neurology 48:1517-1521, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Myers JS, Rauch GM, Rauch RA, et al: Cardiovascular and other risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 903:411-423, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Skoog I: Status of risk factors for vascular dementia. Neuroepidemiology 17:2-9, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Nam CB, et al: Demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors affecting ethnic mortality by cause. Social Forces 744:1419-1438, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar