A Four-Year Study of Enhancing Outpatient Psychotherapy in Managed Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study was a first step in explicitly attempting to open, at least partially, the "black box" of specialty managed mental health care by examining qualitative as well as quantitative aspects of managed outpatient mental health treatment. The Goal Focus Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO) program was studied as an example of a relatively simple, patient-specific, structured educational intervention with a modest capacity to affect practice patterns and care over time among network clinicians. METHODS: Four years of data from an enhanced care management program (N=28,741) designed to facilitate focused, goal-oriented, accountable outpatient psychotherapy and appropriate use of medications were used to illustrate what was actually done in one large national managed behavioral health organization. Random samples of persons from seven matched pairs of GFTPO (N=17,752) and non-GFTPO (N=10,989) employer groups from 1995 to 1998 were studied in a quasi-experimental design. The effects of GFTPO were tested by analyzing samples compared on five measures of outpatient psychotherapy: errors in prescribing medication, continuity of therapists, early termination of treatment, likelihood of multiple treatment episodes, and the use and cost of services. RESULTS: The GFTPO sample showed a lower incidence of medication prescribing errors and therapist switching as well as shorter treatment episodes in the year after the start of outpatient treatment. No differences were observed in the likelihood of early termination or of having multiple treatment episodes. Cost savings did not appear to be at the expense of quality of care. CONCLUSIONS: It is possible to enhance the potential for measuring and influencing the quality of care in large organized systems.

The alliance between managed behavioral health care organizations and psychotherapists continues to be an uneasy one. The anxieties of the provider community have been well documented in the professional literature and in the popular press. Concerns from clinicians and patients include threats to the therapeutic alliance, patient confidentiality issues, ethical quandaries about undertreatment, and undue restrictions on freedom to practice (1,2,3,4). Less well reported are the experiences of managed behavioral health organizations in managing outpatient psychotherapy. Although the relatively new organizations have become expert in the oversight of acute and intensive services, the large majority of patients receive outpatient psychotherapy.

The primary challenge for managed behavioral health organizations is to determine how much management is necessary to ensure appropriate care while minimizing the associated friction and not spending undue administrative resources on the management of treatment; psychotherapy will, in all likelihood, self-limit in fewer than 20 sessions (5,6). In addition, market pressures to justify the administrative costs associated with care management have intensified. In approaching this task, some organizations may be overly aggressive in their management of outpatient therapy, thereby lending substance to clinicians' concerns.

Ultimately, given that managed behavioral health organizations provide almost no direct care to the patient except at the point of access (evaluation and referral), they can demonstrate improved quality of care only if they can positively influence the practice patterns within their clinical network. The literature is replete with examples, almost exclusively from the medical community, of various and innovative efforts to influence providers' behavior that have met with mixed success (7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). Serious questions remain as to whether a managed behavioral health organization is able to positively influence therapists. The likelihood of such influence might be considered poor at best, because the organization's very presence or management style may have alienated these same therapists. The approach to care management presented in this study differs from the attempts reported in the literature in two major ways: care management is focused on the individual patient, and treatment is concurrently reviewed.

Until recently, data were not available on fully enrolled populations that assessed the effect of managed care on indicators of quality. Carve-out managed behavioral health organizations require vast amounts of real-time information to meet their oversight responsibilities. Managed behavioral health organizations rely on electronic information exchange. Over the past decade, the predominant form of managing specialty mental health and substance abuse benefits for members of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and non-HMO health plans has become the carve-out model of behavioral health care (18,19,20,21,22,23,24). Sequential research, using databases of carve-out managed behavioral health organizations, demonstrated that comprehensive mental health benefits were affordable in a managed system in the private sector (23,24,25,26,27) and that a managed behavioral health organization could control costs while maintaining or increasing access to enhanced benefits over time (25,26,27,28,29). This most current research has attempted to determine whether enhanced benefits, improved access, and reduced costs can be accomplished without compromising the quality of care (30,31,32,33,34,35). Although concerns about restrictions on psychiatric treatment under managed care are numerous, there have been no empirical data on how managed care affects the course or quality of therapy.

We describe the findings from a specialized program of flexibly managed outpatient psychotherapy—Goal Focused Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO)—implemented in 1992 by the employer division of United Behavioral Health (UBH; USBH before January 1997). An important observation in the early days of managed care was that treatment planning of any kind was conspicuously absent from most clinicians' repertoires. This absence was noted, impressionistically, to be more apparent in the case of master's-level—as contrasted with doctoral-level—clinicians. The primary purpose of the GFTPO project was to influence that situation by facilitating focused, goal-oriented psychotherapy for all disciplines. A secondary objective was to provide a nonintrusive, cost-effective means of studying treatment processes and outcomes. It was also hypothesized that focused treatment would be more efficient and might result in fewer sessions; however, the program was not specifically designed to shorten the duration of outpatient treatment.

From an initial pilot program in 1992 with only one employer group, GFTPO grew in volume and complexity. As of January 2000, a total of 15 employer groups were participating in GFTPO, creating a nationwide base of approximately 640,000 covered employees and dependents representing varied industries such as utilities, telecommunications, manufacturing, retail, insurance, education, and government. The study reported here is limited to the seven large employers who participated continually in GFTPO for 48 months from 1995 to 1998 (N=325,000). Forty-four percent of the membership resided in the Midwest and 25 percent in the West, with the remaining population equally spread between the East, Southeast, and Southwest United States.

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the effects of a strategy for improving the quality of care in a managed behavioral health setting on a large subpopulation of voluntary users of specialty managed care services. This study examined the effects of two interventions that are intrinsic to GFTPO. First, providers were offered a template of treatment goals consistent with their working diagnosis early in the treatment planning process; second, regular audits of all medication regimens were conducted by a UBH staff psychopharmacologist (36,37). It was our hypothesis that these interventions would promote outpatient treatment that was more efficient and of a higher quality. This study examined several variables to measure this hypothesis: errors in prescribing medication, early termination from treatment, a measure of the patient-therapist alliance, and the use and cost of services.

Methods

Design overview

A controlled, population-based, nonexperimental study design was chosen to evaluate the effects of GFTPO on derived quality measures, utilization, and costs. A large sample of outpatients treated in the GFTPO program were compared with a comparable sample of patients who were receiving usual UBH managed care. The equivalence of the groups was addressed in two ways. First, employer groups that were matched for industry type, geographic region, and benefit design were selected. Second, we controlled for small differences in patient characteristics (described below) that were observed between the groups by using random regression models. Because this study involved in-house retrospective review of databases with no individual identifying information, and with all patients of the covered employers receiving the same care, approval by an institutional review board was not deemed necessary.

Description of the GFTPO program

The GFTPO program enhanced usual UBH care management by focusing providers' attention on a common situation—the clinician's often inadequate preparation for treatment planning—and did so from the outset of treatment while integrating psychopharmaceutical oversight. Attention to treatment planning began with the initial ten-visit authorization for services that the provider received; included was a brief description of GFTPO and a notice asking the provider to make a provisional diagnosis after the first or second session. On receipt of the initial diagnosis, UBH generated a list of treatment goals that were consistent with the patient's DSM-IV diagnosis.

Treatment goals were generated by specialized software developed for the GFTPO program and integrated into UBH's care management system. The software generated treatment goals for each DSM-IV diagnosis on the basis of the symptoms and psychosocial consequences of the disorder.

For example, the diagnosis-related goals for dysthymia are a decrease in depressed mood, a decrease in appetite disturbance, a decrease in crying or tearfulness, a decrease in irritability, a decrease in pessimism, a decrease in sleep disturbance, a decrease in social withdrawal and isolation, a decrease in suicidal risk and self-endangering behavior, elimination of substance abuse, an increase in the ability to cope with stressors, an improvement in academic or occupational functioning, an increase in accurate appraisal of level of control, an increase in effectiveness in daily productivity, an increase in interest in pleasurable activities, stabilization on medications, and assessment and stabilization of physical pathology by a physician.

When the clinician received the potential treatment goals from UBH, he or she was asked to select the most appropriate goals for the patient from the list provided. The provider was free to add individualized treatment goals as needed and was not required to select any of the goals listed. The list of goals was offered as a template for the formulation of an appropriate treatment plan. In the GFTPO process, providers were encouraged to share the tasks of selecting and rating the treatment goals with the patient. Because network providers may have received infrequent GFTPO referrals relative to all referrals from UBH, instructions and reminders were repeated throughout the course of treatment. Network providers were expected to participate in the GFTPO program if they were referred a member from one of the participating GFTPO employer groups. Twenty-two percent of UBH network providers (N=8,041) participated at least once in the program. It should be noted that UBH does not use capitated payments; all services are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis.

Treatment goals were printed on personalized forms that the provider used to request additional sessions or to report termination of treatment. The form incorporated a 5-point Likert rating scale with which the clinician reported the progress achieved for each of the patient's treatment goals each time the clinician requested additional sessions (usually ten).

With the authorization for additional services, the clinician received an updated version of the patient's treatment plan, which reflected any revisions that the treating clinician had submitted to UBH. The clinician was asked to update the agreed-upon treatment plan in his or her next report to UBH. Thus the clinician continually updated an established treatment plan, noting the patient's improvement and use of medications at regular treatment intervals (every ten sessions). Although clinicians may have submitted no or several requests for additional services, all therapists submitted a termination summary for GFTPO patients.

The second core feature of the GFTPO program was routine oversight by the clinical psychopharmacologist (35). With each request for additional sessions, clinicians were required to document whether patients were taking psychiatric medications, the medication prescribed, the dosage, and the prescribing physician. After the decision to authorize additional care had been made by the care manager, the psychopharmacologist audited the case to assess whether the medication regimen was appropriate and congruent with the symptoms, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment goals documented. The GFTPO audit program implemented a zero-tolerance policy for potential medication problems, such as inappropriate polypharmacy or failure to change the dosage or prescription when the patient's symptoms worsened. If concerns emerged and the prescribing physician was a UBH network psychiatrist, the psychopharmacologist would contact the psychiatrist, the treating psychotherapist, or both to discuss the problem. If the prescribing physician was a psychiatrist outside the UBH network or a nonpsychiatric physician, the psychopharmacologist or the care manager would contact the treating psychotherapist and encourage him or her to obtain a release to permit clarifying concerns with the prescribing physician. Resolution of the problem typically involved correcting the diagnosis, changing the treatment, or correcting documentation in the treatment plan. The psychopharmacologist also gave feedback to the care manager.

Non-GFTPO outpatient psychotherapy cases were managed in a manner that was comparable to that for GFTPO cases. The key differences between the GFTPO and non-GFTPO patients were that for non-GFTPO patients the provider was not given a template of potential treatment goals to be used in the formulation of a treatment plan and was not reminded of the original goal-specific treatment plan when requesting additional psychotherapy and medication sessions. Only the GFTPO cases were routinely audited by the psychopharmacologist.

There were no dedicated GFTPO care managers or protocols for utilization management—all patients were managed by the same care managers. The psychopharmacologist and staff medical directors are available for consultation on any case being managed by UBH. All care managers were trained by the psychopharmacologist. Also, the care managers could have directly intervened (for GFTPO and non GFTPO patients) when prompted by problem indicators, such as when patients were not receiving medications when the diagnosis or symptom pattern suggested that pharmacotherapy would have been worth considering or when there was split pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy and insufficient evidence that the two clinicians were maintaining appropriate communication.

Matching employer groups

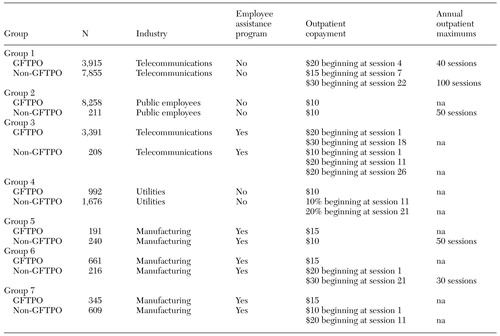

To control for employer characteristics that might have biased the study findings, non-GFTPO groups were selected to match GFTPO employers on industry type and benefit design. Key characteristics for each matched pair of employers are compared in Table 1. Comparisons between the GFTPO and matched non-GFTPO patients further controlled for demographic and diagnostic differences in patient characteristics by using random regression analysis.

Sample selection

Among the 14 employer groups (seven GFTPO and seven non-GFTPO) selected for this study, a total of 28,741 patients began an outpatient episode between July 1, 1995, and December 31, 1997. The sample comprised 17,752 GFTPO patients and 10,989 non-GFTPO patients. Because the GFTPO program addressed outpatient psychotherapy in the UBH provider network, patients receiving medication management only or psychotherapy solely from a nonnetwork provider were excluded from this analysis. Of the patients in the selected GFTPO employer groups, 91 percent were treated within the UBH clinical network. The analysis included all age groups and diagnoses, and no other exclusion criteria were applied. Data for the entire sample were included.

Quality-of-care measures

Four indicators of quality of care were derived to determine whether GFTPO enhanced clinicians' treatment efforts. Each measure was calculated at the level of the treatment episode. A treatment episode was defined as a continuous period of treatment for which the time between sequential dates of service was not greater than 90 days.

The first measure was "therapist switching" and was a measure of therapeutic continuity. This variable was measured as the number of different outpatient therapists used by a patient during his or her index treatment episode. The greater the number of therapists, the greater the extent of therapist switching, an indicator of weaker continuity.

The second measure examined the likelihood of early termination. Early termination was defined as a treatment episode that involved no more than three sessions.

The third measure was the likelihood of having multiple treatment episodes and was defined as having two or more discrete treatment episodes during the study period.

The fourth measure examined the likelihood of a provider's submitting a treatment plan to UBH with a potential medication problem. Eight types of medication problems were routinely flagged for resolution on all GFTPO treatment plans: the medication did not appear appropriate given the provider's diagnosis, symptoms were unchanged or worsening and the prescription was unchanged, inappropriate polypharmacy was used, the patient had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder without a prescription for a mood stabilizer, a tricyclic antidepressant was prescribed in the presence of suicidal ideation, there was a medication dosage problem, an addictive medication was prescribed for a person with a history of substance abuse, and there was evidence that the therapist and the prescriber were not communicating in the case of patients for whom more than one provider was involved in treatment.

The fourth measure was obtained by auditing a sample of individual treatment plans selected from the overall sample. The total intended sample size was 560: a total of 40 treatment plans were randomly selected from each of the 14 employer groups. Of those, 555 audits contributed data to the analysis; one small GFTPO employer group was able to contribute only 35 audits to the analysis. For the purposes of this study, each audit was conducted on a computer-generated version of the treatment plan in which essential data from the medical record were abstracted from the care management information system. Records were blinded as to whether the case was from the GFTPO sample or the non-GFTPO sample.

Cost and utilization measures

Cost and utilization were totaled for a 12-month period after the start of the first treatment episode occurring during the study period. These two variables were grouped into several service categories, including psychotherapy only, all outpatient care, all inpatient care, and total costs and utilization. Costs were estimated as the UBH net paid amount with and without patient copayments. Utilization was measured as the count of the number of outpatient visits and the number of days in a hospital or alternative acute care setting experienced by the patient during the 12-month period.

Patients' demographic characteristics and diagnoses

Characteristics such as age, sex, and the patient's relationship to the insured subscriber were readily available from the UBH data system. Additional characteristics of interest included ethnicity, educational level, and income. These characteristics were not available at the individual level from UBH data systems. As a proxy, data from the U.S. Census Bureau were extracted at the ZIP code level on the proportion of the population with at least a bachelor's degree, the proportion of the population that is nonwhite, and the proportion of the population living under the poverty level in the patient's community. Thus socioeconomic characteristics were at least partially estimated at the ZIP code level.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of utilization and cost data were based on random regression models using matched pairs of employers as clustering variables (38). The mixed-model procedure in SAS (PROC MIXED) was used to accommodate the study design containing a random clustering variable (matched pairs of employer groups), a random cluster-level GFTPO effect (df=6), and several fixed effects measured at the patient level, such as age, sex, relationship to subscriber, and diagnosis (39). All predictor variables that were entered as covariates in the random regression models are listed in Table 2. Random regression models allowed for varying numbers of patients within clusters, an important consideration given the disparities in size between the employer groups.

A preliminary examination of the dependent cost and use variables suggested that distributions were positively skewed. A natural log transformation of these variables appeared to normalize these distributions. Regression coefficients for the effects of the GFTPO program were interpreted as proportionate differences in cost and use between the GFTPO sample and the non-GFTPO sample after taking the antilog of the coefficient minus 1 (40). For example, a coefficient of −.10 would indicate 10.5 percent lower costs or use for GFTPO patients than for non-GFTPO patients.

Dichotomous dependent variables, including the presence or absence of early termination, multiple treatment episodes, and medication errors, were estimated with a generalized linear mixed-model approach using the SAS GLIMMIX macro (39). The GLIMMIX macro implements the Wolfinger-O'Connell procedure for estimating generalized linear models with fixed and random effects (41). The variables included in the GLIMMIX models were identical to those included in the nondichotomous models. A logistic link function was specified in GLIMMIX, and coefficients resulting from this model are odds ratios reflecting the relative likelihood of early termination or multiple treatment episodes.

Results

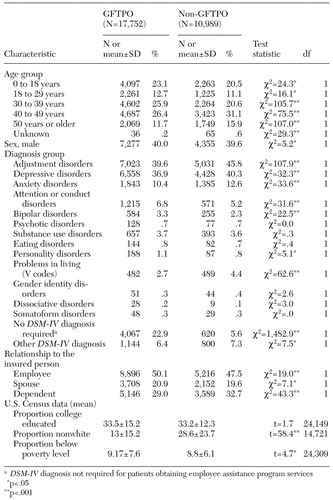

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the GFTPO and non-GFTPO samples are summarized in Table 2. Statistical tests for differences between the samples were significant for most characteristics because the sample was so large. Although the differences were statistically significant, they are probably not clinically meaningful. Age, sex, and diagnosis were dummy coded and used as covariates in the regression models. Socioeconomic status variables, which were geocoded from the U.S. Census Bureau, were also included as covariates.

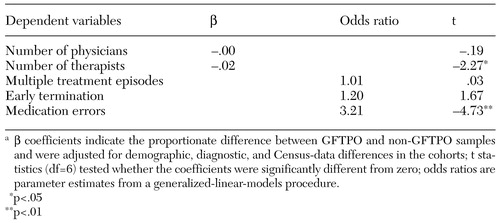

GFTPO and quality of care

There was a strong association between the GFTPO program and a decreased likelihood of medication errors. In a generalized linear model controlling for age, sex, and diagnosis, medication errors were estimated to be approximately three times as likely in the non-GFTPO sample as in the GFTPO sample, as shown in Table 3. To help explain whether reductions in medication errors were related to the amount of experience that a provider had with the GFTPO program, a logistic model was created by regressing the probability of a medication error onto two factors: the total number of patients whom the provider had been referred in the previous two years by UBH (GFTPO and non-GFTPO) and the proportion of the provider's patients who were being managed in the GFTPO program. The results suggested that errors were not related to the total number of patients referred by UBH but were negatively related to the proportion of GFTPO patients (OR=.89, p<.02). These analyses suggest that it was not more experience with the UBH care management system per se but the cumulative experience with GFTPO, especially medication oversight and consultation, that was associated with a lower likelihood of medication errors.

Analyses of the three other measures suggested that quality of care was the same or better when treatment involved GFTPO than when it did not. As shown in Table 3, GFTPO was associated with lower rates of therapist switching and use of fewer therapists per outpatient treatment episode. No difference in the switching of psychiatrists was observed between the GFTPO and non-GFTPO samples. The results of analyses involving indicators for very brief episodes and multiple treatment episodes indicated no differences between the GFTPO and non-GFTPO samples (Table 3).

GFTPO and cost and use

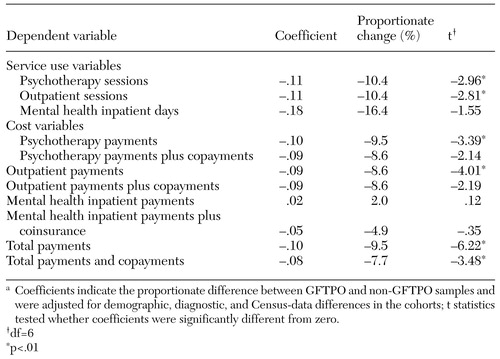

Patients in the GFTPO cohort appeared to have significantly shorter outpatient treatment episodes than those in the non-GFTPO cohort as measured by the number of outpatient and psychotherapy visits. The regression coefficients shown in Table 4 indicate that the GFTPO sample had approximately 5 percent fewer outpatient and psychotherapy visits than the non-GFTPO sample (9.6±9.31 and 11.4±10.3, respectively). The GFTPO program was not associated with significant reductions in inpatient days, although statistical power for these analyses was affected by the small number of patients who had any inpatient use.

Table 4 also lists regression coefficients for the log-expenditure models, indicating that shorter outpatient episodes translated into savings in psychotherapy, total outpatient, and overall annual treatment costs. The magnitude of savings ranged from 6 percent to 11 percent annually, with demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and socioeconomic status controlled for. Total cost savings did not include the administrative costs of the GFTPO program, which had been estimated at $.06 per employee per month.

Discussion and conclusions

The study of the GFTPO program is a first step in explicitly examining qualitative as well as quantitative aspects of managing outpatient treatment in large, dispersed populations. Our findings suggest that a relatively straightforward strategy for encouraging a goal-focused approach to outpatient psychotherapy combined with pharmacotherapy audits appeared to reduce the duration and total cost of mental care health while maintaining or improving the quality of care. Two aspects of these findings are noteworthy. First, the GFTPO program did not operate by changing utilization review practices (42,43). The program targeted providers' early treatment planning and attempted to encourage providers to attend to the goals that were consistent with patients' diagnoses and needs and to do so with the patients' participation. GFTPO attempted to introduce into routine managed care a feasible, minimally intrusive, facilitating process for the development of an appropriate patient-focused treatment plan. By doing so, GFTPO is an example of the potential for managed care to effect cost savings by proactively encouraging clinically appropriate care.

Second, the GFTPO program aimed to influence clinicians in improving the quality of patients' experience in treatment. Analyses of proxies for an enhanced therapeutic alliance showed mixed support for the effects of the GFTPO program. On one hand, the patients in the GFTPO sample were seen by fewer different therapists, on average, than the patients in the non-GFTPO sample. If GFTPO patients were more likely to stay with a therapist through the completion of treatment, this may have been due to therapists' greater engagement of the patient in planning the treatment (44,45,46). On the other hand, very brief episodes of treatment (no more than three sessions) were not less common in the GFTPO sample, as initially expected. We had anticipated that the GFTPO program, as an early intervention in treatment planning, could reduce the occurrence of early termination. The absence of this finding might suggest that the GFTPO program was better suited to strengthening an already established alliance. In cases in which the alliance was not yet established or was very tenuous, as with treatments that ended in fewer than three sessions, GFTPO may not have been a sufficient intervention. It is also worth noting that the definition of early termination as an episode of three sessions or less is arbitrary, and such events should not be viewed as homogeneous. A certain number of planned treatments of one to three sessions were probably included and could have had successful outcomes. Very brief treatment is not necessarily unplanned, inappropriate, or evidence that the therapeutic alliance has been breached (47,48). Because this study did not differentiate duration of treatment by diagnoses, our interpretation of this finding cannot go further.

The finding of no difference regarding very brief episodes is important in understanding the GFTPO effect on the overall duration of outpatient treatment episodes. An increased duration of very short outpatient episodes would have raised concerns that the program was increasing rates of premature termination. The results are reassuring in that they do not indicate premature termination as a source of the reduced cost of outpatient treatment. Reductions in the average duration of an episode (a mean of 9.6 visits for the GFTPO sample and 11.4 for the non-GFTPO sample) were not achieved by increasing the number of very short episodes but by decreasing the number of longer episodes.

The major finding in terms of the improved quality of care was the lower likelihood of medication errors in the GFTPO sample than in the non-GFTPO sample. Concerns about the appropriateness of the use of psychopharmaceuticals continue to increase (49). Interventions by a clinical pharmacist have been determined to be effective in influencing physicians' prescribing behavior. In addition to carrying the influence of the managed behavioral health organization, we suspect that the power of the UBH pharmacist's intervention was that it was an educational consultation that was not directly tied to decisions that authorize continued care. Because providers have, unfortunately, often come to expect that calls from a managed care organization will be criticisms of their clinical judgment or arbitrarily result in nonauthorization of care, the consultative nature of the pharmacist's intervention created a collegial rather than an adversarial interaction. The pharmacist advised the provider of her concerns, requested updated information on the patient, offered education as needed, and made recommendations on dosage, augmentation, or alternative medications. In rare instances in which the pharmacist and the provider were unable to reach consensus, the pharmacist would recommend a second opinion with a network psychiatrist. During the four-year study period, a second opinion was recommended only six times. Providers were typically receptive to the consultation offered and, as our results suggest, the consultation affected their subsequent prescribing behavior.

To assess professionals' perspectives on the program, a single letter survey was sent to participating clinicians in 1997 (48 percent response rate, N=879 respondents). The results of the survey suggested that providers who had more exposure to GFTPO (defined as more than four patients under GFTPO in a 12-month period) reported more favorable experiences with GFTPO than did providers with less exposure. Furthermore, 40 percent of the respondents reported that GFTPO had an impact on the manner in which they conduct their practice with non-GFTPO or non-UBH patients. However, there was a significant difference among disciplines in the response to GFTPO; master's-level social workers and counselors were more favorably inclined toward the program than psychiatrists or psychologists. As with the pharmacist intervention, it was probably the educational aspects of the GFTPO model—providing a structure for the development of an appropriate treatment plan for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy—that was most likely to influence some providers' practice.

Another aspect of a therapeutic alliance is consensus about the outcome of treatment. Analyses of the correlation between estimates of the outcome of treatment by patients and therapists, which were available in the GFTPO program, were not conducted for the non-GFTPO patients. Therefore, no comparisons were possible. Overall, patients and therapists in the GFTPO program agreed in their perceptions of treatment, as measured on a customized GFTPO survey. They agreed on the direction but not the extent of the improvements, with therapists reporting greater progress than patients did. We cannot judge whether this difference might be an artifact of the managed care context.

However, the methodologic limitations of this study require serious consideration. This was not a randomized study. The GFTPO employers were more likely to have employee assistance programs integrated with their mental health benefits and may have employed fewer persons from ethnic minorities. How these characteristics might have affected who sought treatment, who remained in treatment, who responded to requests for information, and who did not are unanswered questions. The response rates were low, because only one letter was sent to patients and providers, and the decision was made not to engender additional expense to get higher rates through more follow-up. As an outcomes measure, GFTPO would have been strengthened by the addition of baseline or pretreatment measures.

Given its limitations, this study is best understood as an initial exploration of the potential for population-based, qualitative investigations in national managed behavioral health organizations. Because few outcome studies have been conducted in managed care, this study supports the feasibility of future controlled trials. To expand the study of treatment outcomes, UBH has shifted the GFTPO project to a broader prospective survey of adult outpatients before and after treatment beginning in 2002. The new program builds on the strengths of GFTPO while providing valid and reliable clinical outcome data.

This quasi-experimental, naturalistic study introduced limited but promising possibilities. Contrary to concerns of public and professional communities that managed care organizations seek only to reduce costs through tactics such as restricting access by "gatekeeping" and denial of care, the GFTPO program demonstrated that managed care has the potential to reinforce best practices and improve clinical effectiveness and accountability. At least, the described processes emphasize the importance of treatment planning and of the use of appropriate medication regimens. At its simplest, the GFTPO program was a patient-specific, structured, population-based, educational intervention with the capacity to shift practice patterns and have an impact on care over time. As we try to focus more clearly on actual practice in managed behavioral health organizations and their capacity and responsibility to enhance the quality of care provided, we can use data from this study to remind us that modest, inexpensive process interventions with positive outcomes are possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the important consultation of Barbara J. Burns, Ph.D., Norman Clemens, M.D., Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., Nada Stotland, M.D., M.P.H., and Kenneth Wells, M.D., M.P.H. They also thank Bernice Friesen, Pharm.D., and Laura Altman, Ph.D.

Dr. Goldman is senior vice-president for behavioral health sciences, Ms. McCulloch is vice-president for health informatics and data integrity, and Dr. Cuffel is vice-president for research and evaluation at United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94105-2426 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Participating Goal Focus Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO) groups and matched non-GFTPO groups

|

Table 2. Characteristics of the Goal Focus Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO) groups and matched non-GFTPO groups

|

Table 3. Results of random regression models of the association between Goal Focus Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO) quality-of-care indicatorsa

a β coefficients indicate the proportionate difference between GFTPO and non-GFTPO samples and were adjusted for demographic, diagnostic, and Census-data differences in the cohorts; t statistics (df=6) tested whether the coefficients were significantly different from zero; odds ratios are parameter estimates from a generalized-linear-models procedure.

|

Table 4. Random regression models of the association between Goal Focus Treatment Planning and Outcomes (GFTPO) and use and cost of mental health servicesa

a Coefficients indicate the proportionate difference between GFTPO and non-GFTPO samples and were adjusted for demographic, diagnostic, and Census-data differences in the cohorts; t statistics tested whether coefficients were significantly different from zero.

1. Tuttman S: Protecting the therapeutic alliance in this time of changing health-care delivery systems. International Journal of Psychotherapy 47:3-16,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Saakvitne KW, Abrahamson DJ: The impact of managed care on the therapeutic relationship. Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy 11:181-199,1994Google Scholar

3. Sabin JE: The therapeutic alliance in managed care mental health practice. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 1:29-36, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mechanic D: Managed care, rationing, and trust in medical care. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 75:118-122, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz S, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115-123, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Expenditures for the treatment of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:883-888, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Davis D, Thompson M, Oxman A, et al: A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 274:700, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pippalla RS, Riley DA, Chinburapa V: Influencing the prescribing behavior of physicians: a metaevaluation. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 20:189-198, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Axt-Adam P, VanDer Wouden J, VanDer Does E: Influencing behavior of physicians ordering laboratory tests: a literature study. Medical Care 31:784-794, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hill M, Weisman C: Physicians' perception of consensus reports. Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 7:30-41, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Davis D, Taylor-Vaisey A: Translating guidelines into practice. Canadian Medical Association Journal 157:408-416, 1997Google Scholar

12. Braybrook S, Walker R: Influencing prescribing in primary care: a comparison of two different prescribing feedback methods. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 21:247-254, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Grol R, Zwaard A, Mokkink H, et al: Dissemination of guidelines: which sources do physicians use in order to be informed? International Journal of Quality Health Care 10:135-140, 1998Google Scholar

14. Freemantle N, Bloor K: Lessons from international experience in controlling pharmaceutical expenditure: II. influencing doctors. British Medical Journal 312:1525-1527, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Frank R, McGuire T: The economics of behavioral health carve-outs. New Directions for Mental Health Services 78:41-47, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Azocar F, Cuffel B, Goldman W, et al: Dissemination of guidelines for the treatment of major depression in a managed behavioral health care network. Psychiatric Services 52:1014-1016, 2002Link, Google Scholar

17. Azocar F, Cuffel B, Goldman W, et al: The impact of evidence-based guideline dissemination for the assessment and treatment of major depression in a managed behavioral healthcare organization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

18. Oss M, Drissel A, Clary J: Managed behavioral health market share. Behavioral Health Industry News 1997, page 1Google Scholar

19. Sturm R: Tracking changes in behavioral health care: how have carve-outs changed care? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:360-371, 1999Google Scholar

20. Frank R, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, et al: Some economics of mental health 'carve-outs.' Archives of General Psychiatry 53:933-937, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Frank R, McGuire T: The economic functions of carve-outs in managed care. American Journal of Managed Care 25:31-39, 1998Google Scholar

22. Goldman W, Sturm R, McCulloch J: New research alliances in the era of managed care. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:107-110, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Cost and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17 (2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar

24. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Cost and incentives in a mental health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

25. Sturm R, Goldman W, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse parity: a case study of Ohio's state employees' program. Journal of Mental Health and Economics 1:129-134, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Huskamp HA: How a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan affected spending for episodes of treatment. Psychiatric Services 49:1559-1562, 1998Link, Google Scholar

27. Goldman W, Cuffel B, McCulloch J, et al: Further evidence for the insurability of expanded mental health coverage. Health Affairs 18(5):172-181, 1999Google Scholar

28. McFarland B, George R, Goldman W, et al: Population-based guidelines for performance measurement: a preliminary report. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 6:23-37, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Grazier K, Eselius L, Hu T, et al: Effects of a mental health carve-out on use, costs, and payers: a four-year study. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:381-389, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Brook R: Managed care is not the problem, quality is. JAMA 278:1612-1614, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Miller R, Luft H: Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7-25, 1997Google Scholar

32. Chassin MR: Assessing strategies for quality improvement. Health Affairs 16(3):151-161, 1997Google Scholar

33. Eddy D: Performance measurement: problems and solutions. Health Affairs 17(4):7-25, 1998Google Scholar

34. Sturm R: Cost and quality trends under managed care: is there a learning curve in behavioral health carve-out plans? Journal of Health Economics 18:593-604, 1999Google Scholar

35. Wells K: Treatment research at the crossroads: the scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:5-10, 1999Link, Google Scholar

36. Cohen L: The emerging role of psychiatric pharmacists. American Journal of Managed Care 5:S621-S629, 1999Google Scholar

37. Sax MJ, Friesen B: The role of pharmacy in supporting behavioral health care quality improvement initiatives. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 6:S17-S22, 1999Google Scholar

38. Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Flay BR: Random regression models for clustered data: with an example from smoking prevention research. Journal of Clinical Consulting Psychology 62:757-765, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Littell RC, Milliken AG, Stroup WW, et al: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute Inc, 1996Google Scholar

40. Kennedy P: A Guide to Econometrics. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 1992Google Scholar

41. Wolfinger R, O'Connell M: Generalized linear models: a pseudo-likelihood approach. Journal of Statistical Computer Simulation 48:233-243, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Koike A, Klap R, Unutzer J: Utilization management in a large managed behavioral health organization. Psychiatric Services 51:621-626, 2000Link, Google Scholar

43. Sturm R: How does risk sharing between employers and a managed behavioral health organization affect mental health care? Health Services Research 35:761-774, 2000Google Scholar

44. Eckert P: Acceleration of change: catalysts in brief therapy. Clinical Psychology Review 241-253, 1993Google Scholar

45. Chinman M, Allende M, Weingarten R: On the road to collaborative treatment planning: consumer and provider perspectives. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:211-218, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Frank E, Kupfer D, Siegel L: Alliance not compliance: a philosophy of outpatient care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:11-17, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

47. Bloom B: Planned short-term psychotherapy: a clinical handbook. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn and Bacon, 1992Google Scholar

48. Howard K, Kopta M, Krause M, et al: The dose-effect relationship in psychotherapy. American Psychology 41:159-164, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Lansky D: Measuring what matters to the public. Health Affairs 17(4):40-41, 1998Google Scholar