Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Symptoms of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood psychiatric condition for which evidence-based treatments have been established. This study describes use of complementary and alternative medicine among children with ADHD or at risk of having ADHD and explores possible predictors of use of such treatments. METHODS: A sample of 1,615 parents of elementary school students in a public school district were interviewed in a telephone screening survey of ADHD symptoms and use of traditional and nontraditional ADHD treatment. A total of 822 parents had a child with a diagnosis of ADHD, had a child in whom ADHD was suspected, or had a child about whose emotions or behavior the parents or school staff had general concerns. RESULTS: Use of complementary and alternative medicine was significantly higher among children who had received a diagnosis of ADHD (12 percent) or in whom ADHD was suspected (7 percent) than among those about whom parents or school staff had general concerns (3 percent). Faith healing had been used for 4 percent of the 822 children. Nontraditional treatments were more likely to have been used among children with a diagnosis or a suspected diagnosis of ADHD and those whose parents used the Internet as a source of information than among other children. CONCLUSIONS: Providers should inquire about nontraditional interventions and educate families about evidence-based approaches when treating children with ADHD.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood psychiatric disorder (1) for which evidence-based pharmacological and psychosocial treatments have been developed (2,3,4,5). The short-term efficacy of stimulant medication treatment in particular is well supported by more than two decades of research (2,6,7). Nevertheless, for many families pharmacological treatment for childhood ADHD remains controversial (8,9,10,11,12). Reluctance among parents to have their child receive stimulant medication may contribute to their seeking nontraditional treatments (13,14,15,16), even though none of these treatments merit a scientific rating as an established treatment for ADHD (16,17).

Estimates of the use of nontraditional treatment—also referred to as complementary and alternative medicine—among children range from 9 percent to 46 percent and vary by type of treatment, study population, time period, and geographic region (15,18,19,20,21,22). Common nontraditional treatments for children include elimination diets, dietary supplements, herbal regimens, homeopathy, massage, acupuncture, and biofeedback (18,23,24). Religious approaches, such as faith healing, may also be a used as an alternative intervention for childhood behavioral problems (25). To our knowledge, only one study has examined nontraditional treatments for ADHD. In a clinical sample of 290 Australian children with ADHD, 64 percent had received alternative therapies, the most common of which was the use of special diets (26).

The prevalence and patterns of use of alternative medicine for children with diagnosed or suspected ADHD have several important clinical and health policy implications. Parents who suspect that their child has ADHD may elect to use nontraditional interventions without obtaining a professional diagnostic assessment, which may mean that the child will receive treatment that is not clinically indicated. Additionally, if alternative medicine is used in lieu of established treatments, parents may not have the opportunity to receive recommended patient education about effective treatment options and the adverse effects of delaying care (27).

Clinicians also need to be aware of nontraditional interventions in order to develop treatment plans that address potential drug interactions with natural remedies, such as the effect of St. John's wort on the metabolism of prescription medications, and to identify potential risks of specific alternative medicine interventions, such as neuropathy as a consequence of megavitamin therapy (28,29). Moreover, because nontraditional treatments are not addressed in professional ADHD practice guidelines or parameters (27,30,31,32), these sources provide no guidance on the clinician's role in eliciting information on use of complementary and alternative medicine or in counseling parents on the efficacy or potential harm of such interventions.

The objectives of this study were threefold: to describe the use of four types of complementary and alternative medicine—chiropractic, homeopathy, massage, and acupuncture—and of faith healing for symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, or poor concentration; to examine whether use of these approaches varies with parental concerns about ADHD; and to identify potential independent predictors of nontraditional interventions, such as sociodemographic characteristics, parents' knowledge about ADHD, and the severity of symptoms. Parental concern was examined because it is related to the detection of behavioral disorders and help-seeking behavior (33,34,35,36,37,38). We hypothesized that nontraditional treatment is more common among children whose parents suspect a diagnosis of ADHD than among children whose parents have general concerns about their child's behavior, activity level, or attention span.

Methods

Sampling

School registration records were used to identify 12,009 elementary school students enrolled in kindergarten through fifth grade during the 1998-1999 academic year in a north central Florida public school district. A gender-stratified random sampling design was used to oversample girls by a margin of two to one to ensure adequate representation. A total of 3,158 students were selected by this means.

Only one child per household was eligible for the study to ensure subject independence. Children were eligible if they lived in a household with a telephone, were not receiving special education services for mental retardation or autism, and were Caucasian or African-American. Children from other ethnic groups were excluded because they accounted for less than 5 percent of the total student population. More information about the sample has been published elsewhere (39).

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained in procedures approved by the institutional review board of the University of Florida and the school district research director, and telephone interviews of parents were conducted from October through December 1998. The interview included inquiries into the child's health status and use of health services, the parent's knowledge and attitudes about ADHD, and standardized child behavior ratings. After the interview, permission was sought to ask the child's homeroom teacher to complete similar child behavior rating scales.

Participation

Contact was made with 2,035 parents, or 64 percent of the sample. Seventy-nine percent of these agreed to participate, yielding 1,615 completed interviews. Parental permission to administer teacher behavior questionnaires was obtained from 1,549 (96 percent) of the respondents, and questionnaires were mailed to homeroom teachers. Of these, 1,187 (77 percent) were completed and returned.

Measures

Levels of ADHD-related parental concerns. Children were assigned to one of four mutually exclusive categories on the basis of their parents' responses to 26 survey questions assessing ADHD detection and use of services: diagnosed ADHD, suspected ADHD, general behavioral concerns, and no concerns. Parents were asked whether they had any general concerns that their child may have an emotional or behavioral problem, including overactivity, impulsivity, inattention, or poor concentration; whether they suspected that their child had ADHD, attention-deficit disorder, attention deficit, or hyperactivity; whether school staff had voiced general concerns or suspicions of ADHD; and whether their child had ever had a professional evaluation for ADHD.

If the child had received a diagnosis of ADHD by a professional, he or she was categorized as having "diagnosed ADHD." A child was categorized as having "suspected ADHD" if the parents or school staff suspected ADHD but no diagnostic assessment had been sought. If the parents or school staff had concerns about the child's emotions or behavior—that is, activity level, impulsivity, inattention, or poor concentration—but no suspicion of ADHD, the child was placed in the "general behavioral concerns" category. The remaining children were in the "no concern" category. Together, children in these first three categories were considered to be at risk of having ADHD.

Child and parent characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, race, and lunch subsidy status, were obtained from school district administrative records. Lunch status, which is based on federal government guidelines involving family income, was identified as subsidized and nonsubsidized, with subsidized lunch status corresponding to lower socioeconomic status (SES). SES scores were also calculated with the Hollingshead four-factor index, which can range from 8 (lowest social stratum) to 66 (highest) (40).

Parents' knowledge about ADHD was assessed with survey questions designed to serve as indicators of general familiarity with ADHD for nonclinical populations and modeled after the AIDS knowledge and attitudes section in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (10,41).

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever heard about attention-deficit disorder, hyperactivity, ADD, or ADHD and to describe the recency and amount of their knowledge of ADHD as well as the information sources on ADHD they used most commonly (for example, the Internet). The questions also probed beliefs about the role of sugar as a causative agent and of medications as a possible treatment for ADHD. A knowledge summary score was constructed, ranging from 0, least amount of knowledge, to 5, highest amount of knowledge. In a previous study with participants of similar sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge summary scores had a normal distribution (mean±SD= 2.6±1.6, median=3) (10). Internal consistency (coefficient alpha) was .73, and test-retest agreement of the individual survey questions ranged from 73 to 100 percent (N=59) (10).

The severity of behavioral problems was assessed with parent and teacher report forms of a standardized screening measure, the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, version IV (SNAP-IV) checklist, which is a rating scale consisting of operationalized DSM-IV criteria for ADHD (42). The internal consistency of the original SNAP was reportedly high (greater than .9 for all symptom clusters), and two-week test-retest reliability was .7 for inattention items, .8 for impulsivity items, and .9 for hyperactivity items. Norms have been established for the SNAP for boys and girls of elementary school age for average ratings per item (42). Scores that are two standard deviations above the norm indicate severe symptom levels.

Traditional and nontraditional treatments. Parents whose children fell into the categories of diagnosed ADHD, suspected ADHD, or general behavioral concerns were asked about lifetime use of both traditional and nontraditional treatments. For children currently receiving traditional treatment, parents indicated the type of provider and treatment modalities used.

A child was identified as having received a nontraditional treatment modality if the parent answered yes to the question "Have you ever used any of the following to help your child with hyperactivity, impulsivity, or concentration problems: chiropractor? massage therapy? homeopathic therapy? acupuncture? faith healing?" The first four of these types of nontraditional treatment were selected on the basis of literature reports of their common use in child populations (15). In addition, school administrative data were used to determine whether children received exceptional student education services.

Data analysis

The procedure outlined by Aday (43) was used to adjust estimates for sampling and nonparticipation effects. This process was made possible by the availability of administrative data (gender, race, lunch subsidy status, and special education category) for all eligible students. In the first stage of weight development, an expansion weight (the inverse of the selection probability) was computed for each subject, adjusting for disproportionate sampling. The expansion weight calculation depended on the child's gender and the number of eligible children in a household.

In the second stage of weight development, 12 weighting classes were formed on the basis of factors for which a significantly different response was noted; these included race, lunch subsidy status, and special education service status (44). To adjust for differential response rates, the expansion weight was divided by the response rate within each weighting class to form a response-adjusted weight.

In the third stage of weight development, a relative weight was constructed by dividing each response-adjusted weight by the mean response-adjusted weight. This scaling step effectively downweighted the number of subjects to equal the actual sample size. The final weight was obtained after trimming of the extreme (the upper and lower 1 percent) values of the relative weights and uniform redistribution of the values so that the actual sample size was preserved.

Bivariate analysis was conducted with a chi square test of proportions for discrete variables and analysis of variance procedures for continuous variables. As part of the latter procedure, pairwise comparisons using the Scheffé estimation technique were conducted (alpha=.05). This procedure was selected because it allows multiple comparisons to be made simultaneously and it remains valid under a wide range of conditions (45). Stepwise regression analysis with an F-to-stay of 3.92 was performed to examine the independent contribution of hypothesized predictor variables—including sociodemographic factors, parents' knowledge of ADHD, severity of children's behavioral problems, and parents' level of concern—to the likelihood that nontraditional treatment would be used for ADHD symptoms. SAS, version 6, and STATA were used to conduct the statistical analyses (45).

Results

ADHD-related parental concerns

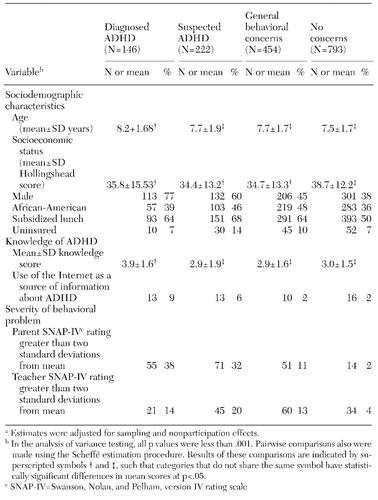

Table 1 summarizes the relationship of parents' concern about ADHD symptoms with the sociodemographic characteristics of the child and family, the parent's knowledge of ADHD, and the severity of the child's behavioral problem. The mean±SD age of the children was 7.7±1.74 years (range, five to 12); 41 percent (N=662) were African American. The mean SES score was 38.4±12.9 (range, 8 to 66, with higher values indicating higher socioeconomic status). Nine percent of the parents (N=146) reported that their child had a diagnosis of ADHD based on a professional evaluation, and ADHD was suspected in an additional 14 percent of the children (N=222). More than a quarter of the parents (N=454, or 28 percent) had concerns that their child had an emotional or behavioral problem, and 49 percent (N=793) had no concerns.

Traditional and nontraditional treatments

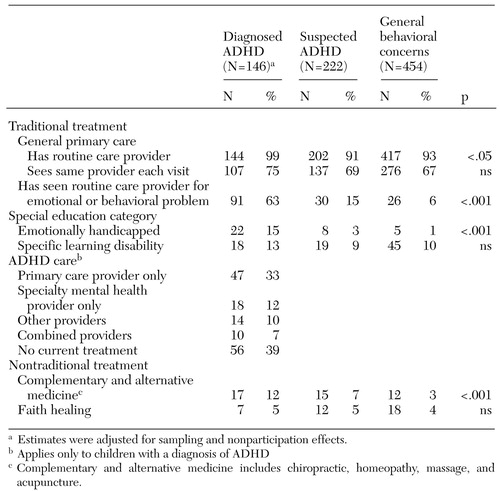

Table 2 summarizes the use of traditional and nontraditional treatments for behavioral problems among children with ADHD or at risk of having ADHD. Of particular note, while almost all children with a diagnosis of ADHD had a routine care provider and most of their parents (N=92, or 63 percent) reported discussing their concerns about ADHD symptoms with the clinician, 39 percent (N=57) were not receiving traditional ADHD treatment.

Among the 822 children with a diagnosis of ADHD or at risk of having ADHD, 5 percent (N=44) had used complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of ADHD symptoms. These interventions included homeopathy (N=24, or 3 percent), massage (N=20, or 2.4 percent), chiropractic (N=14, or 1.7 percent), and acupuncture (N=3, or .4 percent). Faith healing was reported by an additional 4 percent (N=37) of parents. Given that faith healing was rarely (.6 percent) combined with other alternative methods, it was treated as a discrete nontraditional treatment modality. Complementary and alternative medicine interventions, but not faith healing, varied by level of parental concern, such that children with a diagnosis of ADHD had the highest level (12 percent) of such interventions (p<.001).

Users of nontraditional interventions

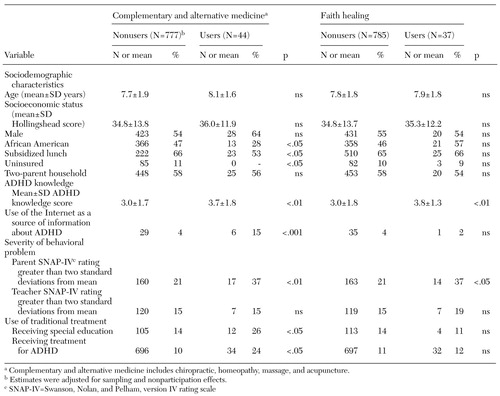

As Table 3 shows, the sociodemographic characteristics of the child and family, indexes of parents' knowledge of ADHD, the severity of the child's behavioral problem, and use of traditional treatment were significantly related to use of complementary and alternative medicine. Children who received complementary and alternative treatments were more likely than those who did not to be Caucasian and covered by health insurance and less likely to be poor. The parents of these children had higher ADHD knowledge scores and more often used the Internet as a source of information about ADHD. Use of complementary and alternative medicine was also associated with greater severity of symptoms and with higher use of traditional services in primary care and special education. In contrast, use of faith healing was related only to higher ADHD knowledge scores and severity of symptoms.

In the stepwise regression model (pseudo R2=.07), three predictors of use of complementary and alternative medicine were retained. A diagnosis of ADHD had the largest effect size and the highest precision (odds ratio [OR]=4.5; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=2.1 to 9.6). Suspected ADHD, as compared with general behavioral concerns, was associated with twice the odds of such use (OR=2.4; CI=1.1 to 5.3), and use of the Internet for information about ADHD tripled the odds (OR=3.2; CI=1.3 to 8.2).

Discussion and conclusions

The overall estimate of use of selected complementary and alternative medicine for symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, or poor concentration in this sample of elementary school students was substantially lower than that reported in the only other published study addressing complementary and alternative medicine use for ADHD (5 percent compared with 64 percent) (26). This discrepancy may be explained by differences in the assessment of nontraditional treatment, because dietary interventions, which made up 94 percent of the alternative therapies in the earlier study, were not assessed in our study. However, the rate of use of complementary and alternative medicine in this school-based population was more similar to that reported for pediatric outpatients (11 percent compared with 5 percent) (15). In that sample, chiropractic and homeopathy were the most commonly used methods, whereas the most popular method in our study was homeopathy, closely followed by massage therapy; the least commonly used was acupuncture.

We hypothesized that the high rate of homeopathy use may be related to several factors. Homeopathic preparations are available over the counter and do not require a visit with an alternative medicine practitioner, making it a less expensive choice than other interventions. Homeopathic preparations also may be seen as "natural" and less invasive than chiropractic or acupuncture, and thus may be more acceptable to parents for use with their children.

While scientific support of the efficacy of nontraditional treatments for ADHD has not been established, there is evidence that parents need to consider potential risks of such interventions. A recent review mentioned pertinent risks in all methods, even those commonly perceived as harmless, such as homeopathy (29), reinforcing the notion that nontraditional treatments should be discussed with the child's traditional health care provider.

As we hypothesized, use of complementary and alternative medicine varied with the specificity of parental concerns. Even though the utility of parental concerns in the detection of developmental and behavioral problems has been well established (33,34,35,36,37,38), specific concerns about ADHD did not predict an eventual diagnosis in a clinical sample of children referred for school problems (46). Thus the fact that 7 percent of children in whom ADHD was suspected had received nontraditional interventions without a professional evaluation and diagnosis should raise some concerns. Use of complementary and alternative medicine also was independently associated with parents' reporting using the Internet as a source of information about ADHD. This relationship may in part reflect the large number of scientifically unsubstantiated recommendations accessible through this medium and merits closer examination as a topic for inclusion in parent education sessions (47,48,49)

Faith healing did not vary by level of specificity of parental concern and was rarely reported by parents who used complementary and alternative medicine. It was more commonly used for children with higher ADHD symptom ratings and by parents with higher ADHD knowledge scores, but its use did not vary by any other user characteristic. To our knowledge, no other study has addressed whether parents use faith healing methods as an alternative ADHD treatment for their children.

Findings from this study should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. The sample was restricted to one geographic region in north central Florida, and the results therefore may not be generalizable to other areas. Parents' reports of a clinical diagnosis of ADHD were not validated with survey information from health care providers or with review of health records. This study was also limited to four types of nontraditional interventions and to faith healing. Dietary measures were not included in this survey because a second phase of the study examined self-care measures, including dietary manipulations, in greater detail. Finally, the relatively low rate of use of complementary and alternative medicine limited our ability to detect significant relationships in this study.

Nevertheless, the study's findings suggest that nontraditional treatments for ADHD symptoms merit further study. Future research should examine the full array of potential complementary and alternative medicine services, including interventions that contain commonly available regional medicinal plants, and should be geographically more diverse to allow broader generalization of findings. Results of such studies could inform future editions of ADHD practice parameters on how to address nontraditional interventions. In the meantime, our findings indicate that health care providers should routinely inquire about the use of complementary and alternative medicine for children with ADHD or in whom ADHD is suspected. Parent education should not only address the evidence base of traditional therapies but also make reference to commonly selected nontraditional methods and comment on the limitations of the Internet as an information source.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants RO1-MH-57399 and R24-MH-51846 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Dana Mason, B.S., for research assistance.

Dr. Bussing is affiliated with the departments of psychiatry, pediatrics, and health policy and epidemiology of the University of Florida, Box 100157 UFHC, Gainesville, Florida 32610-0157 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Zima is with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences of the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Gary is with the College of Nursing and Dr. Garvan is with the department of biostatistics of the University of Florida. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry held October 24-29, 2000, in New York City.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics, parent's knowledge of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and severity of child's behavioral problem, by level of ADHD-related parental concernsa

a Estimates were adjusted for sampling and nonparticipation effects.

|

Table 2. Use of traditional and nontraditional treatments for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms among children with a diagnosis of ADHD or at risk of having ADHD

|

Table 3. Characteristics of users and nonusers of complementary and alternative medicine and of faith healing for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

1. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference: Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Program and Abstracts, in NIH Consensus Development Conference: Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1998Google Scholar

2. Swanson JM, McBurnett K, Wigal T, et al: Effect of stimulant medication on children with attention deficit disorder: a "review of reviews." Special issue: issues in the education of children with attention deficit disorder. Exceptional Children 60:154-161, 1993Google Scholar

3. Pelham Jr WE, Wheeler T, Chronis A: Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 27:190-205, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. The MTA Cooperative Group: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With ADHD. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1073-1086, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. The MTA Cooperative Group: Moderators and mediators of treatment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With ADHD. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1088-1096, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 11 (AHCPR pub no 99-E018). Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1999Google Scholar

7. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al: Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder across the life cycle. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:409-432, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Angold A, Erkanli A, Egger HL, et al: Stimulant treatment for children: a community perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:975-984; discussion 984-994, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, Rogers KM, et al: Explanatory models of ADHD: do they differ by ethnicity, child gender, or treatment status? Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 6:233-242, 1998Google Scholar

10. Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, Perwien AR: Knowledge and information about ADHD: evidence of cultural differences among African-American and white parents. Social Science and Medicine 46:919-928, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bennett DS, Power TJ, Rostain AL, et al: Parent acceptability and feasibility of ADHD interventions: assessment, correlates, and predictive validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 21:643-657, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Liu C, Robin AL, Brenner S, et al: Social acceptability of methylphenidate and behavior modification for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 88:560-565, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

13. Astin JA: Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA 279:1548-1553, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Moenkhoff M, Baenziger O, Fischer J, et al: Parental attitude towards alternative medicine in the paediatric intensive care unit. European Journal of Pediatrics 158:12-17, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Spigelblatt L, Laine Ammara G, Pless IB, et al: The use of alternative medicine by children. Pediatrics 94:811-814, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

16. Baumgaertel A: Alternative and controversial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatric Clinics of North America 46:977-992, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Arnold LE: Treatment Alternatives for ADHD, in NIH Consensus Development Conference: Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 1998Google Scholar

18. Ernst E: Prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine for children: a systematic review. European Journal of Pediatrics 158:7-11, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Faw C, Ballentine R, Ballentine L, et al: Unproved cancer remedies: a survey of use in pediatric outpatients. JAMA 238:1536-1538, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Mottonen M, Uhari M: Use of micronutrients and alternative drugs by children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 28:205-208, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pendergrass TW, Davis S: Knowledge and use of "alternative" cancer therapies in children. American Journal of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology. 3:339-345, 1981Google Scholar

22. Sawyer MG, Gannoni AF, Toogood IR, et al: The use of alternative therapies by children with cancer. Medical Journal of Australia 160:320-322, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al: Unconventional medicine in the United States: prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al: Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 280:1569-1575, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bussing R, Gary FA: Practice guidelines and lay explanatory models of ADHD: friends or foes? Harvard Review of Psychiatry 9:223-233, 2001Google Scholar

26. Stubberfield T, Parry T: Utilization of alternative therapies in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 35:450-453, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Dulcan M, Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:85S-121S, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Obach RS: Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by constituents of St. John's wort, an herbal preparation used in the treatment of depression. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 294:88-95, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

29. Spigelblatt LS: Alternative medicine: should it be used by children? Current Problems in Pediatrics 25:180-188, 1995Google Scholar

30. American Academy of Pediatrics: Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 105:1158-1170, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. American Academy of Pediatrics: Medication for children with attentional disorders. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Children With Disabilities and Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics 98:301-304, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

32. American Academy of Pediatrics: Medication for children with an attention deficit disorder. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Children with Disabilities, Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics 80:758-760, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

33. Garrison WT, Bailey EN, Garb J, et al: Interactions between parents and pediatric primary care physicians about children's mental health. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:489-493, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

34. Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, et al: Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care: prevalence and risk factors. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:1107-1116, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Glascoe FP, MacLean WE, Stone WL: The importance of parents' concerns about their child's behavior. Clinical Pediatrics 30:8-11; discussion 12-14, 1991Google Scholar

36. Glascoe FP: Using parents' concerns to detect and address developmental and behavioral problems. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses 4:24-35, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Glascoe FP, Dworkin PH: The role of parents in the detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatrics 95:829-836, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

38. Glascoe FP: Early detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatrics in Review 21:272-279, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Bussing R: Barriers to help-seeking and treatment for ADHD. Presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, Orlando, Fla, Oct 10-14, 2001Google Scholar

40. Hollingshead: Four Factor Index of Social Class. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, Department of Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

41. Chyba MM, Washington LR: Questionnaires from the National Health Interview Survey, 1985-1989. Vital and Health Statistics 1:131-138, 1993Google Scholar

42. Swanson JM: School-based assessments and interventions for ADD students. Irvine, Calif, KC Publishing, 1992Google Scholar

43. Aday LA: Designing and Conducting Health Surveys. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1996Google Scholar

44. Cox BG, Cohen SB: Methodological Issues For Health Care Surveys. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1985Google Scholar

45. Stata Statistical Software, release 5. College Station, Tex, Stata Corporation, 1997Google Scholar

46. Mulhern S, Dworkin PH, Bernstein B: Do parental concerns predict a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 15:348-352, 1994Google Scholar

47. Lindberg DA, Humphreys BL: Medicine and health on the Internet: the good, the bad, and the ugly. JAMA 280:1303-1304, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Goldstein D, Tuth C: National health and medical websites take off, but to where? Managed Care Interface 12:48-50, 1999Google Scholar

49. Cooke A: Quality of health and medical information on the Internet. Clinical Performance and Quality Health Care 7:178-185, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar