Use of Case Manager Ratings and Weekly Urine Toxicology Tests Among Outpatients With Dual Diagnoses

Abstract

Use of drugs and alcohol by 43 predominantly male outpatients who had severe mental illness and a comorbid substance use disorder were assessed weekly through the ratings of experienced dual disorder case managers and through blinded research urine toxicology tests. The percentage of weeks in which drugs or alcohol were used was calculated on the basis of one or both assessments. The case managers often missed drug use over the weekends, which was detected by the urine toxicology tests. Agreement between the two methods varied widely, even when the ratings were made by highly experienced case managers. These findings have implications for monitoring patients with dual diagnoses and provide insight into the accuracy of case manager ratings.

To understand whether problematic behavior on the part of patients with dual diagnoses is due to their mental illness, their substance use, or both, case managers and the other members of the treatment team need to know whether patients are using drugs or alcohol. Case managers, who often act as the eyes and ears of the treatment team, may use a variety of methods to identify substance use among their patients, ranging from self-report to direct observation. They may also use clinical toxicology reports as well as the reports of landlords, friends, or other patients. This case manager-based substance use assessment method has been described by Drake and colleagues (1,2), Cary and Correia (3), and others (4) as the most practical method for identifying substance abuse among persons with chronic mental illness and is probably the one most used in intensive outpatient programs for persons with dual diagnoses.

Although intensive case managers may have the best and most regularly updated information about their patients, the patients, especially if they are using substances, can avoid or mislead their case managers. Given the inherent limitations of case manager observation and the potential limitations of the established standard in drug abuse research—urine toxicology tests—we studied the relative and combined accuracies of intensive case manager ratings and weekly urine toxicology screens in the detection of drug and alcohol use among outpatients with severe mental illness.

Methods

The study was conducted between July 1998 and July 2000. The study participants were 43 patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders who were attending an intensive case management-based, integrated outpatient treatment program for persons with dual diagnoses; the elements of the program have been described elsewhere (4). The mean±SD age of the patients was 40±7 years, and 35 patients (82 percent) were male. Twenty-six patients (60 percent) were Caucasian, nine (22 percent) were African American, and eight (18 percent) were from other racial groups. The most common primary psychiatric diagnoses were schizoaffective disorder (25 patients, or 57 percent), schizophrenia (seven patients, or 17 percent), recurrent major depression (six patients, or 15 percent), and bipolar disorder (four patients, or 9 percent).

All study participants had actively used drugs or alcohol in the previous six months and qualified for a DSM-IV diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence. They all signed informed consent statements according to the guidelines of the university and were paid each week for completed treatment summaries and urine toxicology screens.

Fourteen case managers arranged to see their patients for scheduled meetings each Monday, after which they made their ratings of the number of days on which the patient had used drugs or alcohol in the previous week. Thirty-eight (90 percent) of the pairs of case managers and patients had worked together for more than a year, and 21 pairs (50 percent) had been together for more than five years. All the case managers had master's degrees and had worked in an integrated dual disorder treatment program for more than two years.

Patients and case managers were blinded to the results of the urine toxicology tests. Each test was conducted by an independent member of the study staff on the same day the case manager rating was made. Urine samples were analyzed by fluorescence polarization immunoassay.

Results

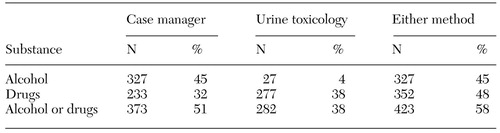

The data for the 43 patients translated to 734 patient-weeks in which case manager ratings of alcohol and drug use could be compared with the results of the weekly blinded urine toxicology tests. The data are summarized in Table 1. The results of the urine toxicology tests were positive for drugs or alcohol in 282 (38 percent) of the 734 weeks. Case manager ratings were positive in 373 (51 percent) of the 734 weeks. In 423 weeks (58 percent), drug or alcohol use was indicated by a urine toxicology test or a case manager rating.

Overall, urine toxicology tests were positive for alcohol in only 27 of the 734 weeks (4 percent), whereas these tests were positive for drugs in 277 weeks (38 percent). The results more likely reflect limitations in the accuracy of urine toxicology analysis for alcohol, given the short half-life of alcohol (5,6), than actual patterns of alcohol use in this sample.

By comparison, case managers made positive ratings of alcohol use in 327 (45 percent) of the 734 weeks, of drug use in 233 weeks (32 percent), and of both alcohol and drug use in 191 weeks (26 percent).

The drugs most commonly detected by urine toxicology tests were cocaine (64 percent of positive samples), marijuana (48 percent), opiates (12 percent), alcohol (9 percent), amphetamines (45 percent), and benzodiazepines (5 percent). Some samples were positive for more than one drug.

For drugs alone, the overall specificity of the case manager ratings against the urine toxicology tests was high (92 percent); only one case manager rating had a specificity below 80 percent (range, 67 percent to 100 percent). This finding indicates that case managers' assessments of abstinence from drugs was highly accurate; variability among the case managers was moderate. On the other hand, sensitivity estimates tended to be low (57 percent; range, 0 to 85 percent), indicating that case managers varied greatly in the accuracy of their assessments of active drug use as identified by urine toxicology tests.

Discussion and conclusions

Weekly urine toxicology tests and case manager ratings of substance use each appeared to have their strengths and limitations in this patient population. Urine toxicology tests, although the method of choice for detecting drug use (5,6,7,8), are clearly inadequate for detecting alcohol use: these tests were positive for alcohol in only 4 percent of the weeks sampled, compared with 45 percent for case manager ratings. To our knowledge, the degree of this discrepancy has not been previously reported.

Furthermore, although it could be argued that urine toxicology tests are never used to evaluate alcohol use in addiction treatment programs, it is the first author's experience, from lecturing and consulting widely across the United States, that many mental health case managers are not aware of this fact. Also, given that alcohol has such a short half-life, neither frequent toxicology screens nor daily breath tests are likely to provide accurate information.

In addition, because this population is likely to be in long-term care, the invasiveness and the cost—$15 to $25 per test—of frequent urine testing would probably be prohibitive. Nor are other laboratory measures, such as gamma-glutamyltransferase (CGT) or carbohydrate-deficient transferin (CDT) levels, sensitive enough to determine when or whether substance use occurred on a particular day or in a particular week. Thus, until better technology emerges, the alcohol use rating of an experienced case manager with a relatively low caseload who sees the patient regularly is probably the most practical method for assessing alcohol use. It is likely that the accuracy of case manager ratings would be severely compromised by larger caseloads and less observation.

In terms of drug use alone, agreement between case manager ratings and urine toxicology tests was much closer—positive results were assigned in 32 percent and 38 percent of the weeks studied, respectively. However, for any given week, agreement occurred only about half of the time—that is, drug use was detected on different weeks, often close together, by the two methods. This suggests that the best method for designating a particular week as drug and alcohol free would be to require both the urine toxicology test and the case manager rating to be negative.

We also found a great deal of variability among individual case managers in the specificity and sensitivity of their ratings of drug use compared with urine toxicology tests. This variability could not be explained by any case manager-related factor we examined: past training in drug or alcohol use treatment, number of years of employment, number of years spent working with patients with dual diagnoses, academic degrees, age, sex, number of subjects, or caseload (17 compared with 25 clinical cases), or even "reputation" (a qualitative assessment by the program director). This finding suggests that the accuracy of all case managers, regardless of their backgrounds, could be improved if the case managers rated their patients' drug use and compared their ratings with the results of urine toxicology tests.

Significant variability among patients was also noted: about 25 percent of the patients always received concordant urine toxicology and case manager assessments, and another 25 percent received nonconcordant assessments more than half of the time. Although it seems likely that using data provided by friends or family members would improve the accuracy of assessments, two recent studies showed such an effect to be small or nonexistent (9,10).

We hope that the results of this study help to elucidate the relative strengths and limitations of urine toxicology tests and ratings by seasoned case managers working with patients who have both serious mental illness and substance use disorders. We also hope that the study has helped to define a measure of substance-free weeks to be used in outcome studies of this patient population.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant 5-R01-DA10838-02 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Anastasia Fisher, D.N.S., and Barbara Maccalla.

Dr. Ries, Dr. Srebnik, Dr. Snowden, and Dr. Comtois are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Washington and Harborview Mental Health Services, 325 Ninth Avenue, Box 35991, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Dyck and Dr. Short are with the research and training division of the Washington Institute for Mental Illness and with Washington State University-Eastern State Hospital in Spokane.

|

Table 1. Weeks during which alcohol or drug use was detected through case manager ratings and urine toxicology tests (N=734 weeks)

1. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201-215, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, Alterman AI, Rosenberg SR: Detection of substance use disorders in severely mentally ill patients. Community Mental Health Journal 29:175-192, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Carey KB, Correia CJ: Severe mental illness and addictions: assessment considerations. Addictive Behaviors 23:735-748, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ries RK (ed): Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Coexisting Mental Illness and Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse. Washington, DC, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1994Google Scholar

5. Shearer DS, Baciewicz GJ, Kwong TC: Drugs of abuse testing in a psychiatric outpatient service. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 18:713-726, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Verebey KG, Buchan BJ: Diagnostic laboratory: screening for drug abuse, in Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook, 3rd ed. Edited by Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, et al. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1997Google Scholar

7. Schiller MJ, Shumway M, Batki SL: Utility of routine drug screening in a psychiatric emergency setting. Psychiatric Services 51:474-478, 2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Schiller MJ, Shumway M, Batki SL: Patterns of substance use among patients in an urban psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 51:113-115, 2000Link, Google Scholar

9. Carey KB, Simons J: Utility of collateral information in assessing substance use among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Substance Abuse 11:139-147, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Griffin ML, et al: The use of collateral reports for patients with bipolar and substance use disorders. American Journal of Alcohol Abuse 26:369-378, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar