Patterns of Substance Use Among Patients in an Urban Psychiatric Emergency Service

Abstract

Data from patients visiting an urban psychiatric emergency service in California were examined to document incidence and patterns of substance use and ethnic differences among users. A total of 392 patients were randomly assigned to receive a drug screen (N=198) or to receive usual care (N=194). Forty-four percent of the mandatorily screened patients had positive screens for any substances: 37 percent were positive for any drugs, and 7 percent were positive for alcohol only. Cocaine was present in 62 percent of the drug-positive screens. Blacks were two and a half times more likely than whites to have positive screens for drugs and five times more likely to have positive screens for cocaine.

Substance abuse can exacerbate symptoms among patients with primary psychiatric disorders and can precipitate visits to emergency services by persons with primary substance use disorders (1). Few recent studies characterize the nature, extent, or ethnic patterns of substance abuse in emergency settings.

In a retrospective review in Cincinnati, 35.7 percent of emergency psychiatric patients received a primary or secondary diagnosis of substance abuse (2). The study examined a 1992 sample of 490 black and white patients; it did not separately examine amphetamine or opiate use. In a retrospective review of 325 suburban Long Island patients visiting a psychiatric emergency service in 1992, a total of 27.7 percent of those screened were positive for alcohol or drugs, with 14.9 percent positive for alcohol, 7.7 percent for cocaine, .7 percent for opiates, and .7 percent for amphetamines (3). The only ethnic pattern noted was that among cocaine abusers, only black patients displayed increased paranoia.

In a 1993 Dallas study, 27.3 percent of psychiatric emergency patients without primary substance abuse diagnoses had positive urine screens for drugs or alcohol (4). The study did not examine ethnic patterns of drug use. In Philadelphia, 31.8 percent of patients who passed through a psychiatric emergency room between 1987 and 1990 before being admitted to inpatient care had positive urine drug or alcohol screens; the study did not examine ethnicity (5). Of 218 consecutive psychiatric emergency patients in Brooklyn in 1991, a total of 34.4 percent screened positive for at least one substance—25.7 percent for cocaine, 3.2 percent for opiates, and 1.4 percent for amphetamines (6). The study did not examine statistics on ethnic patterns of specific drug use.

The study reported here examined more recent rates and patterns of substance use in a psychiatric emergency service. It is the first such study done on the West Coast, and it examined in detail ethnic patterns of use.

Methods

Data were collected in the context of a randomized trial of the effectiveness of mandatory drug screening in the San Francisco General Hospital psychiatric emergency service, the only psychiatric emergency service in the City and County of San Francisco. In fiscal year 1997–1998, a total of 8,379 visits were documented, and 3,551 patients were hospitalized.

All 1,257 patients who visited the service between July 17 and September 26, 1997, were asked to provide informed consent to participate in the study. Consenting patients were randomly assigned to a mandatory drug screen or usual care. Psychiatrists were blind to consent and randomization status and ordered urine drug screens for patients in both groups based on their individual clinical judgment. Drug screens were then automatically ordered for all remaining subjects in the mandatory-screen group. There were 198 subjects in the mandatory-screen group and 194 in the usual-care group.

We collected demographic and clinical information from clinical charts. Results of urine drug screens were obtained from hospital databases. Only the results of the mandatory-screen group are analyzed in this report. These results provide the most accurate picture of substance abuse, because the sample represents a consecutive sample of emergency service patients who all had drug screens ordered.

The drug screens tested for ethanol, amphetamine and methamphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and methadone. Screening was performed with standard immunoassays, and samples that screened positive were confirmed with additional tests. Cutoff concentrations for positive results were similar to those in recommendations from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (7).

Results

Of the 1,257 patients visiting the emergency room during the study period, 392 patients (32 percent) consented to participate. In the mandatory-screen group, the mean±SD age was 37.9±10.6years, and 128 patients (65 percent) were male. A total of 105 patients in the mandatory-screen group (53 percent) were white, 54 (27 percent) were black, 21 (11 percent ) were Hispanic, and 15 (8 percent) were Asian. The majority (171 patients, or 86 percent) were admitted involuntarily.

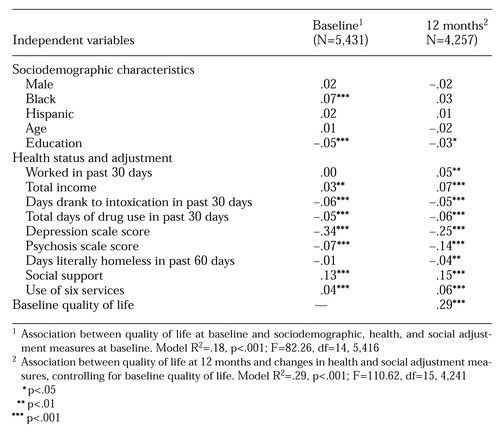

Drug screen results for the mandatory-screen group are presented in Table 1. Of the 198 patients, 53 (43 percent) tested positive for any substance, with 45 patients (37 percent) positive for drugs and eight patients (7 percent) positive for alcohol only. Cocaine was the most common substance, found in 28 (62 percent) of the drug-positive screens. Eighteen of the 45 drug-positive screens (40 percent) showed multiple drugs.

We also conducted a logistic regression analysis, with drug screen results as the dependent variables and ethnicity as the independent variable, using whites as the reference group. Blacks were two and a half times more likely to have positive screens for drugs (p=.03) and five times more likely to have positive screens for cocaine (p<.001). Asians and Hispanics appeared less likely than whites to have positive drug screens (odds ratio=.3 in both groups), but these differences were not statistically significant, possibly due to smaller sample size.

To evaluate the representativeness of the sample of consenting subjects, we compared the 392 consenting subjects with the 865 nonconsenting subjects on a variety of measures. No statistically significant differences between groups in gender or ethnicity were noted. A significant difference was found in age—the consenting subjects were younger (37.5±10.5 versus 39.1±12.8 years; t=2.24, df= 921, p=.025). Because diagnosis may have been unreliably recorded in the hospital database, we compared data from a random sample of 100 nonconsenting patients with data from 194 consenting subjects in the usual-care group.

For both groups, drug screens were ordered at the physician's discretion, and diagnoses were abstracted from charts. No statistical difference was found between groups in discharge diagnosis, except for uncommon diagnoses, which were found in less than 1 percent of subjects. Drug screens were obtained for 30 (30 percent) of the nonconsenting subjects and 91 (47 percent) of the consenting subjects in the usual-care group, a significant difference (χ2=7.999, df=1, p=.005). Of these, 12 nonconsenters (43 percent) and 48 consenters (53 percent) had positive drug screens, which was not a significant difference.

Discussion and conclusions

As expected, substance use was common in this sample of patients visiting an emergency room. Of the 198 patients who received mandatory drug screens, 43 percent had positive screens. Alcohol was present in 14 percent of screens; however, actual alcohol use may be higher because alcohol is detectable in urine for a much shorter period than other drugs. Despite reports of epidemic methamphetamine use on the West Coast as evidenced by a 30-fold increase in admissions for methamphetamine abuse in California since 1983, amphetamine or methamphetamine use was less common than cocaine use (22.2 percent versus 62.2 percent). However, it was more common than reported in previous studies (8).

We found ethnic differences in drug use patterns. Blacks were two and a half times more likely than whites to have positive drug screens and were five times more likely to use cocaine. Asians and Hispanics appeared less likely than whites to have positive drug screens, although this result was not statistically significant.

The low consent rate raises the concern that the sample was not representative. Consenting subjects differed somewhat from nonconsenting subjects, particularly in the rate of screens obtained, but the lack of a significant difference in the proportion of positive screens in these groups suggests that data on consenting subjects provide reasonable estimates of drug use. A major reason for lack of consent was clinicians' failure to pursue consent, rather than patients' refusal.

The 43.4 percent rate of substance use found in our San Francisco sample was higher than that found in psychiatric emergency patients in Cincinnati (35.7 percent), Philadelphia (31.8 percent), Long Island (27.7 percent), Dallas (27.3 percent), and Brooklyn (34.4 percent). This higher rate may indicate particularly high substance use rates in San Francisco, generally high rates on the West Coast, or increasing rates of use among patients presenting to psychiatric emergency rooms. Opiate and methamphetamine use was higher for this San Francisco sample than for samples in previous studies in other cities. This finding is consistent with the city's ranking as first in methamphetamine use and third in heroin use (9). The procedural and organizational effects of different patterns of substance abuse on psychiatric emergency rooms, such as the necessity for routine drug screens, may be a fruitful line for further inquiry.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kate Beyrer, M.D., Mark Leary, M.D., and Aline Wommack, R.N., M.S., for help in initiating and conducting the study; John Osterloh, M.D., M.S., for providing expertise on toxicology screens; and Michele Okun, M.S., for contributions to conducting the study. Dr. Batki's contribution to the study was partly supported by grants R01-DA-1-1397 and P50-DA-09253 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Schiller is assistant clinical professor, Dr. Shumway is assistant professor, and Dr. Batki was formerly clinical professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Schiller is also an attending psychiatrist at San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Batki is currently professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York Health Science Center in Syracuse. Send correspondence to Dr. Schiller at the Department of Psychiatry, San Francisco General Hospital, 7M-Ward 21, 1001 Potrero Avenue, San Francisco, California (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results of Urine drug screens for 198 patients receiving mandatory drug screens in an urban psychiatric emergency service

1. Breslow RE, Klinger BI, Erickson AJ: Acute intoxication and substance abuse among patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service. General Hospital Psychiatry 18:183-191, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Strakowski S, Loezak H, Sax K, et al: The effects of race on diagnosis and disposition from a psychiatric emergency service. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:101-107, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dhossche D, Rubinstein J: Drug detection in a suburban psychiatric emergency room. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 8:59-69, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gilfillan S, Claasen C, Orsulak P, et al: A comparison of psychotic and nonpsychotic substance users in the psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 49:825-828, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Sanguinetti V, Brooks M: Factors related to emergency commitment of chronic mentally ill patients who are substance abusers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:237-241, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

6. Elangovan N, Berman S, Meinzer A, et al: Substance abuse among patients presenting at an inner-city psychiatric emergency room. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:782-784, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Department of Health and Human Services: Mandatory guidelines for federal workplace drug testing programs: final guidelines notice. Federal Register 53:11969-11989, 1989Google Scholar

8. Gorman M: Speed use and HIV transmission. Focus 11:4-6, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rouse BA: Epidemiology of illicit and abused drugs in the general population, emergency department drug-related episodes, and arrestees. Clinical Chemistry 42 (8, part 2):1330-1336, 1996Google Scholar