Priorities of Consumers, Providers, and Family Members in the Treatment of Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study explored the extent and nature of agreement on outcome and service priorities between consumers, their providers, and their family members as well as providers' and family members' awareness of consumers' priorities. METHODS: Interviews were conducted with members of 60 stakeholder sets that included a person with schizophrenia, one of his or her mental health care providers, and one of his or her family members. Each member of the set ranked seven outcomes and nine services in order of importance and rated the relative importance of each. Family members and providers also ranked the outcomes and services in the order in which they believed the consumer would rank them. Magnitude-estimation-preference-weight ratios and Kendall's rank-order correlation were used to evaluate pairwise (consumer and provider, consumer and family member, and family member and provider) and within-set agreement. RESULTS: Pairwise and within-set agreement was low. In general, no more than a third of the pairs agreed on outcome priorities, and no more than half agreed on service priorities. In about half of the 60 sets, none of the three pairs agreed on outcome priorities. Awareness of consumers' priorities was limited. Family members' and providers' estimates of consumers' outcome priorities were more similar to their own preferences than to consumers'. Low rates of agreement were also noted for providers' estimates of consumers' service priorities. Within-set agreement was lower than agreement by type of stakeholder. CONCLUSIONS: Current goal-setting in nonresearch clinical settings is generating neither consensus nor a shared understanding of consumers' priorities. Priorities vary widely among consumers, among providers, and among family members.

For philosophical and practical reasons, there is increasing emphasis on the incorporation of the consumer's preferences into decisions about clinical care (1,2). Consideration of consumers' preferences respects the role of the individual who is receiving care and is also likely to increase the person's sustained involvement in care (3,4). In the mental health field, literature on goal attainment and the working alliance emphasizes the importance of agreement between the consumer and the provider on the objectives and tasks of treatment for sustaining involvement in care and improving outcomes (5,6,7,8). Experience with programs for the family members of persons who have schizophrenia suggests that expanding their understanding of and agreement on the objectives of treatment also increases the likelihood of good consumer outcomes and sustained involvement in care (9,10).

The literature on goal attainment, the working alliance, and family intervention is clinically oriented. It focuses on the individual consumer and on achieving agreement within individual stakeholder sets—that is, the consumer, the consumer's family, and the consumer's providers. However, most of the literature on preferences in relation to schizophrenia focuses on agreement between groups of consumers, groups of providers, and groups of family members rather than on agreement within the more clinically relevant stakeholder sets (11,12,13,14,15,16).

Although a few reports have provided linked data on service preferences (17,18), to our knowledge this is the first published report providing survey data on within-set agreement on both outcome and service priorities of specific individuals with schizophrenia. In addition, we present findings on pairwise agreement (pairs of consumers and providers, pairs of consumers and family members, and pairs of providers and family members within sets), agreement by type of stakeholders (all consumers, all providers, and all family members), and awareness of consumers' priorities on the part of family members and providers.

Methods

Study design and participants

We studied 60 sets of stakeholders, each comprising a consumer with schizophrenia, a member of the consumer's family, and one of the consumer's mental health care providers. A nonprobability sample of eligible consumers who were participating in an ongoing longitudinal study was recruited. Consumers who were Arkansas residents, were between the ages of 18 and 70 years, met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, had both a family member and a mental health care provider who were willing to participate in the study, and had been in contact with the family member at least once a month were eligible.

The study was approved by the joint human research advisory committee of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System. After the participants had received a detailed description of the study and their questions had been answered, they all provided written informed consent. Each participant received $30 as compensation.

Data collection

Data on service and outcome priorities were collected through individual interviews that used ranking and magnitude estimation techniques. These techniques are standard, commonly used elicitation methods (19,20) that are feasible for use with persons with schizophrenia (14,21,22,23,24). Ranking requires respondents to place a series of items in order of importance to them. Magnitude estimation requires respondents to indicate how much more desirable or important each item is than a standard item—in this case, the least important item; for example, the respondent might rank an item as two, seven, ten, or 55 times as desirable as the least important item (25).

The interviews, conducted between July 1999 and April 2000, used common scripted procedures for all types of stakeholders to minimize interviewer bias. To elicit outcome preferences, a trained research assistant gave each participant a set of seven cards and asked him or her to place them in order of importance. Each card described one of the positive outcomes of treatment listed in Table 1. Participants were then asked about the relative importance of each outcome—magnitude estimation. The consumers were asked to respond in terms of how important it was to them personally to achieve each outcome. Each consumer's family member and provider were asked to answer the question in terms of how important they thought it was for the consumer to achieve the outcome. Analogous procedures were used to elicit priorities for nine services, also listed in Table 1. Selection of these seven outcome and nine service domains was based on expert consensus on the major aspects of an individual's life that are affected by schizophrenia and the basic services required to provide comprehensive care (26,27,28,29).

To evaluate awareness of the consumer's priorities, the family member and the provider were asked to rank the seven outcomes and nine services in the order they believed the consumer in their set would rank them.

Classification of agreement

We examined agreement on the outcome and service priorities separately, in each case assessing the frequency of agreement by pairs and within stakeholder sets. We quantified the frequency of pairwise agreement on the outcome rankings by using Kendall's rank-order correlation coefficient (tau). Pairs were considered to agree on outcome priorities if tau was .429 or greater. Given that there were seven outcomes, this cutoff reflects a one-tailed alpha of .068 and is the cutoff with the alpha value closest to the standard alpha of .05 (30). We used a liberal one-tailed alpha to maximize the likelihood of a pair's being considered to be in agreement.

We summarized pairwise agreement on outcome weights by using average magnitude-estimation-preference-weight ratios (average MEPRs), an approach modeled on standardized mortality ratio analysis (31). To derive a pairwise average MEPR, we first generated domain-specific standard magnitude estimation preference weights for each stakeholder by dividing that stakeholder's rating of the relative importance of each domain by the sum of his or her ratings for all domains. We then calculated the ratios of domain-specific weights (the MEPRs) for each pair and averaged the pair's seven domain-specific MEPRs. Pairs with an average outcome MEPR between .5 and 2 were considered to agree. An average MEPR in this range indicates that, on average, the relative importance one stakeholder gives to a particular outcome is no more than twice that given to it by the other stakeholder.

Pairwise agreement on rankings of services and their importance weights was assessed analogously. Given that there were nine service items, the cutoff for tau closest to a one-tailed alpha of .05 was a tau of .444 or greater (alpha=.06).

Within-set agreement was summarized in terms of the number of stakeholder pairs in agreement in a set, ranging from zero (no pairs in a set in agreement) to three (all possible pairs in agreement). This process generated four measures of within-set agreement: agreement on outcome rankings, agreement on outcome weights, agreement on service rankings, and agreement on service weights.

Because agreement on the relative importance of each service or outcome may be less important than agreement on which items have the highest priority, we also examined the frequency with which the top three priorities reported by the provider and the family member in a set included the consumer's top priority.

To explore the frequency with which within-set agreement can be inferred from aggregate data on linked groups of consumers, providers, and family members, we calculated the mean ranking given to each outcome by each type of stakeholder. We used these means to rank-order outcomes for each type of stakeholder and compared the rankings among the three types by using Kendall's rank-order correlation coefficient. Service rankings for each type of stakeholder were generated analogously.

Pairwise and within-set assessments based on rankings were repeated to evaluate providers' and family members' awareness of consumers' priorities. For these analyses, we compared the consumers' rankings with the estimates of consumers' rankings elicited from their providers and family members.

Results

Sample

The mean±SD age of the consumers was 47.3±8.2 years (range, 30 to 69 years). Forty-one consumers (68 percent) were men; 34 consumers (57 percent) were European American, and 26 (43 percent) were African American. The 60 family members included parents (27 family members, or 45 percent), siblings (16, or 27 percent), spouses or significant others (eight, or 13 percent), and other relatives (nine, or 15 percent).

The mean age of the family members was 56.4±17.3 years (range, 19 to 89 years). Most were women (51 family members, or 85 percent). The racial distribution of the family members corresponded to that of the consumers. The mean±SD age of the 36 providers, who represented 13 agencies, was 42.9±10.9 years (range, 26 to 68 years). Twenty-six providers (72 percent) were women, 30 (83 percent) were European American, 19 (53 percent) held professional degrees, and 27 (75 percent) participated in a single interview. The providers had been working with the consumers in their sets for a mean duration of 3.9±3.3 years (range, less than one year to 20 years).

Agreement on outcome priorities

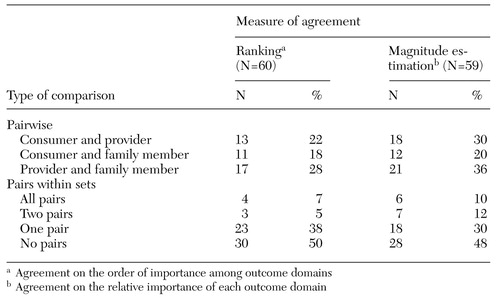

As the data in Table 2 show, the extent of pairwise agreement on outcome priorities was low. In general, no more than a third of the pairs agreed on priorities, regardless of the types of stakeholders or the measure of agreement used. Agreement was lowest for pairs of consumers and family members and highest for pairs of providers and family members, although these differences were not significant. Within-set agreement was correspondingly low; in about half of all the sets, no stakeholder pairs were in agreement. In only 12 percent of the sets were two or more pairs in agreement on ranking. In 22 percent of the sets, two or more pairs agreed on relative weights (magnitude estimation). Although rates of agreement differed by the measure used, the differences were not significant.

The consumer's top outcome priority was among the top three priorities of the provider in 35 sets (58 percent), of the family member in 29 sets (48 percent), and of the provider and the family member in 18 sets (30 percent). The numbers of sets in which the consumer's first and second outcome priorities were included among the other stakeholders' top three priorities were much lower (15 sets, or 25 percent; ten sets, or 17 percent; and five sets, or 8 percent, respectively).

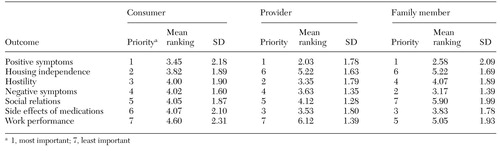

The mean priority rankings given to each outcome by each type of stakeholder are listed in Table 3. The extent of agreement among the three types was greater than that within individual stakeholder sets. Nonetheless, several differences stood out. Providers and family members ranked housing independence as less important and control of side effects as more important than did consumers. Family members ranked control of negative symptoms as more important than did either consumers or providers.

Agreement on service priorities

Pairwise agreement on service priorities was more frequent than that on outcome priorities, but fewer than half of the pairs agreed, regardless of the type of stakeholders or the agreement measure used. Again, the extent of agreement was smallest for pairs of consumers and providers (16 to 25 pairs, or 27 to 42 percent) and greatest for pairs of providers and family members (24 to 29 pairs, or 41 to 49 percent), and the differences were not significant. The extent of within-set agreement was also greater for service priorities than for outcome priorities. In about a third of the sets (16 to 24 sets, or 27 to 41 percent), two or more pairs agreed; in another third, one pair agreed (21 to 22 sets, or 36 to 37 percent); and in a final third (13 to 22 sets, or 22 to 37 percent), no pairs agreed. Differences in rates of agreement by measure of agreement were not significant.

The consumer's top service priority was among the top three priorities of his or her provider in 25 of 59 sets (42 percent), of his or her family member in 29 sets (49 percent), and of both the provider and the family member in 19 sets (32 percent). The consumer's first and second priorities were included among the provider's top three priorities in 14 sets (24 percent), among the family member's top three priorities in ten sets (17 percent), and among both stakeholders' top three priorities in four sets (7 percent).

Agreement on ranking was greater among types of stakeholders than within stakeholder sets. The mean rankings given to the nine services by consumers and family members were virtually identical. Providers ranked programs that teach self-care skills as less important than did other stakeholders, whereas they ranked case management services and psychoeducation programs as more important. (Data are available on request.)

Subgroup analyses

Although not a specific aim of this study, patterns of agreement were compared by consumers' sex, employment status, race, frequency of service contact, and housing status. Patterns did not differ by sex or employment status. However, the data suggested that in stakeholder sets in which the consumer had service contact at least once a month, agreement between the family member and the provider was greater. Also, the outcome and service priorities of African-American family members were more likely to diverge from those of both the consumer and the provider in their set than was the case for European-American family members, and consumers who lived independently were more likely to share priorities with the family member and the provider in their set than those who lived in supervised housing. Although these findings were inconsistent, they merit further investigation.

Awareness of consumers' preferences

Substituting providers' and family members' estimates of consumers' priorities for the stakeholders' own priority rankings had little effect on the rates of agreement. If anything, the rates were lower when providers' and family members' estimates of consumers' priorities were substituted for the provider's and family member's own rankings, although the differences were not significant.

On average, a provider's estimate of the priority rankings of the consumer in his or her set was more likely to agree with the provider's own preferences than with the consumer's priorities. Providers' rankings and their estimates of consumers' rankings agreed 57 percent of the time for outcome priorities (34 of 60 pairs) and 76 percent of the time for service priorities (45 of 59 pairs), whereas providers' rankings and consumers' actual rankings were in agreement only 22 percent of the time for outcome priorities (13 pairs) and 27 percent of the time for service priorities (16 pairs). Similarly, the rankings of family members' and their estimates of consumers' rankings were in agreement 45 percent of the time (24 pairs) for outcome priorities and 54 percent of the time (32 pairs) for service priorities, whereas the rankings of family members and the rankings of consumers were in agreement only 18 percent of the time (11 pairs) for outcome priorities and 37 percent of the time (22 pairs) for service priorities. For providers, the differences in outcome rankings and service rankings were significant (χ2= 15.42, df=1, p<.001 and χ2=28.54, df= 1, p<.001, respectively). For family members, the differences were significant for outcome priority rankings (χ2=9.86, df=1, p=.002) and approached significance for service priority rankings (p=.065).

The consumers' top outcome priority was included more frequently among the providers' and family members' estimates of the consumer's priorities than among these stakeholders' own top three priorities, but the differences were not significant. The pattern for service priorities was less consistent. Again, the differences were not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

Pairs of consumers and providers and pairs of consumers and family members rarely agreed on the relative importance of change in seven outcome domains. The extent of agreement on the consumer's top outcome priorities was somewhat greater. Agreement on the relative importance of nine types of services was greater than agreement on outcome priorities.

Although the size of the sample severely limited the power of subgroup analyses, our data suggested that patterns of agreement may differ by consumers' race, frequency of service contact, and housing status. Potential differences by race are particularly worrisome and warrant further research.

Low rates of stakeholder agreement on priority rankings were accompanied by low levels of awareness of consumers' priorities. Substitution of providers' or family members' estimates of consumers' preferences did not improve pairwise agreement. Indeed, family members' and providers' estimates of consumers' priority rankings were more similar to their own rankings than to the consumers'.

Preference data have most often been reported as the average ratings or rankings for stakeholder groups or types. There is a growing body of literature on stakeholder group preferences related to schizophrenia care (11,12,13,14,15,16,21). Published studies vary in terms of the number and nature of domains covered, the ways in which the domains are defined, the measurement strategies used, and the stakeholder groups studied. These variations make it difficult to compare findings across studies. It is clear, however, that not all domains are considered equal and that different types of stakeholders place different values on specific outcomes and services.

For example, providers tend to value control of symptoms, medication management, and case management more highly than other stakeholders do, whereas consumers and family members tend to value social support, housing, and medical and dental services more highly (2,12,16,18,32). Despite these differences, the literature reflects substantial agreement between types of stakeholders. Our group data are consistent with reported patterns of variation and patterns of general agreement between types of stakeholders. It is notable, however, that the impression of agreement among stakeholders was substantially greater in our study when average rankings were compared among types of stakeholder than when within-set data were analyzed.

There are potential limitations to the generalizability of our data. First, to our knowledge, no consensus criteria exist for what constitutes clinically meaningful agreement on outcome or service priorities. Although the cutoffs we used to classify agreement were relatively liberal, even more liberal cutoffs would have increased the rates of agreement we observed. Second, the data pertained to a limited sample of consumers receiving care in a single state and may not be generalizable to other parts of the country. Third, only one family member and one provider was interviewed for each consumer. Although these two individuals were chosen by the consumer, were generally those who had most frequent contact with the consumer, and were most involved in the consumer's daily life and treatment, it is possible that other family members or providers would have had different priority patterns and rates of agreement. Finally, to be eligible to participate in the study, a consumer had to have a family member and a provider who were also willing to participate. This eligibility criterion effectively excluded individuals who were not in close contact with their families and those who did not have a usual care provider. The fact that data were collected through interviews may have increased social desirability bias, particularly for consumers and family members. However, it is likely that any such selection or response bias would have led to higher rates of within-set agreement than would have been observed among stakeholders with less frequent contact.

If replicated, our findings have both clinical and research implications. The consumers in our study were receiving treatment from a broad array of public-sector agencies. The extent to which discussion of goals or formal goal setting was a routine aspect of care was neither an eligibility criterion nor an exclusion criterion for consumers or providers. In this context our findings suggest that usual practice is generating neither consumer-provider consensus nor a shared understanding of consumers' preferences.

Similarly, the data suggest that current levels of contact between providers and family members and between consumers and family members are not generating consensus or shared understanding of consumers' goals. Reported preferences are often not shared, and even a top priority of the consumer is often not what other stakeholders believe it is. Goals are not mutually exclusive, and multiple goals can be pursued simultaneously. Nonetheless, ascertaining the specific goals that consumers want to address first is important.

Furthermore, outcome priorities vary widely among consumers, as they do among family members and providers. The goals of individual stakeholders cannot be accurately inferred from group data, and aggregate data from consumer groups cannot be assumed to reflect the priorities of any individual consumer. Providers who want to incorporate consumers' preferences into treatment planning or use them to involve families must continue to elicit preferences from individual consumers.

An understanding of the preferences of the various types of stakeholders is essential for cost-effectiveness analyses and for resource allocation. However, from a clinical perspective, it is within-set agreement and differences in stakeholders' preferences that will affect care for an individual client. Thus we need a better and fuller understanding of the relationships between agreement, the process of care, and sustained involvement in care. In particular, we need to know more about usual clinical practice, the extent to which the goals of consumers and providers are explicitly discussed, the extent to which family members are brought into the discussion, the factors that influence these patterns, and the impact of consensus on subsequent treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants IIR-98-094 and IIR-94-109 from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) and grants RO1-MH-55170 and P50-MH-48197 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Owen's work on this project was supported by an HSR&D Advanced Research Career Development Award (RCD-94-311). The authors thank Leslie Bragg, M.A., Edie Nichols, M.R.C., Rhonda Willborg, A. J. Naylor, Allen Morse, M.Sc., Mary Richardson, and Barbara J. Burns, Ph.D.

Dr. Fischer and Dr. Owen are affiliated with the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System and the Centers for Mental Healthcare Research at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Dr. Shumway is with the psychiatry department of the University of California, San Francisco, at San Francisco General Hospital. Send correspondence to Dr. Fischer at the Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Mental Healthcare and Outcomes Research (152/NLR), Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, 2200 Fort Roots Drive, Building 58, North Little Rock, Arkansas 72214 (e-mail, [email protected]). Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Health Services Research held June 21-23, 2000, in Los Angeles and at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association held November 12-16, 2000, in Boston.

|

Table 1. Outcome and service domains rated by 60 consumer-provider-family member setsa

a Participants are instructed to put the seven outcomes (printed on cards) in order of importance to them, starting with the most important and working down to the least importantOnce the domains have been ranked, participants are asked to state the magnitude of the differences in importance between the domains (magnitude estimation). The process is then repeated with the nine services.

|

Table 2. Agreement on outcome priorities between sets and pairs of consumers, providers, and family members

|

Table 3. Mean rankings of outcome priorities for each type of stakeholder

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General: Executive Summary. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999Google Scholar

2. Wilson N: Agreement among clients, collaterals, and clinicians regarding service need and treatment outcomes for chronically mentally ill persons, in Proceedings of the First Annual National Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research and Program Evaluation, Arlington, Va, Feb 7-9, 1990Google Scholar

3. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637-651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Donovan JL: Patient decision making: the missing ingredient in compliance research. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 11:443-455, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bordin ES: The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy 16:252-260, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Gaston L: The concept of the alliance and its role in psychotherapy: theoretical and empirical considerations. Psychotherapy 27:143-153, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Horvath AO, Greenberg LS: Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36:223-233, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Kiresuk TJ, Smith A, Cardillo JE: Goal Attainment Scaling: Applications, Theory, and Measurement. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1994Google Scholar

9. Dixon LB, Lehman AF: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679-687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cradock JA, Young AS, Forquer SL: Patient and family preferences regarding outcomes of treatment for severe, persistent mental illness. Los Angeles, ULCA/RAND Research Center for Psychiatric Disorders, Working Paper 197, Aug 2000Google Scholar

12. Teague GB: Priorities for outcomes of mental health services among consumers, families, and providers, in Proceedings of the Fifth Annual National Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research and Program Evaluation, San Antonio, Tx, Jan 28-31, 1995Google Scholar

13. Lee TT, Ziegler JK, Sommi R, et al: Comparison of preferences for health outcomes in schizophrenia among stakeholder groups. Journal of Psychiatric Research 34:201-210, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Revicki DA, Shakespeare A, Kind P: Preferences for schizophrenia-related health states: a comparison of patients, caregivers, and psychiatrists. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 11:101-108, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

15. Finn SE, Bailey JM, Schultz RT, et al: Subjective utility ratings of neuroleptics in treating schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 20:843-848, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hatfield AB, Gearon JS, Coursey RD: Family members' ratings of the use and value of mental health services: results of a national NAMI survey. Psychiatric Services 47:825-831, 1996Link, Google Scholar

17. Rogers ES, Danley KS, Anthony WA, et al: The residential needs and preferences of persons with serious mental illness: a comparison of consumers and family members. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21(1):42-51, 1994Google Scholar

18. Crane-Ross D, Roth D, Lauber BG: Consumers' and case managers' perceptions of mental health and community support service needs. Community Mental Health Journal 36:161-178, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Edwards W: Use of multiattribute utility measurement for social decision making, in Conflicting Objectives in Decisions. Edited by Bell DE, Keeney RL, Raiffa H. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

20. Patrick DL, Erickson P: Health Status and Health Policy: Allocating Resources to Health Care. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

21. Shumway M: Preference weights for cost-outcome analyses of schizophrenia treatments: comparison of four stakeholder groups, in pressGoogle Scholar

22. Hargreaves WA, Shumway M, Hu T: Aggregating outcome measures, in Cost-Outcome Methods for Mental Health. San Diego, Calif, Academic, 1998Google Scholar

23. Shumway M, Chouljian T, Battle C: Stakeholder preferences for schizophrenia outcomes: an evaluation of assessment methods [abstract]. Schizophrenia Research 24:258, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Shumway M, Battle C: Clinicians' preferences for schizophrenia outcomes: a comparison of four methods [abstract]. Schizophrenia Research 15:197, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Froberg DG, Kane RL: Methodology for measuring health-state preferences: II. scaling methods. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 42:459-471, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Rosenblatt A, Attkisson CC: Assessing outcomes for sufferers of severe mental disorder: a conceptual framework and review. Evaluation and Program Planning 16:347-363, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Caring for people with severe mental disorders: a national plan of research to improve services. DHHS pub no (ADM)91-1762, Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

28. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(4 suppl):1-63, 1997Google Scholar

29. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, and co-investigators of the PORT project: Translating research into practice: the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Siegel S, Castellan NJ Jr: Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1998Google Scholar

31. Kahn HA, Sempos CT: Statistical Methods in Epidemiology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989Google Scholar

32. Maddy BA, Carpinello SE, Holohean EJ, et al: Service and residential need: recipient and clinician perspectives. Proceedings of the Second Annual National Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research and Program Evaluation, Arlington, Va, Oct 2-4, 1991Google Scholar