A Model for Managed Behavioral Health Care in an Academic Department of Psychiatry

Abstract

In response to the effects of the managed care environment on patient flow and care, the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine developed and has been managing a capitated behavioral health care program. The program is responsible for providing mental health and substance abuse services for 22,000 members of the TRICARE Uniformed Services Family Health Plan (USFHP), directed by the U.S. Department of Defense. The integration of primary care and behavioral health care is a major feature of the USFHP/TRICARE program. The authors describe the transition from a carve-out for-profit managed care organization to the integrated program managed by the department. During the first two years of the program, access to services increased and use of inpatient services decreased without the need to deny service use. To supplement previous reports of the involvement of academic psychiatry departments in behavioral health care, the authors supply utilization and financial data that may serve as benchmarks for similar efforts by other departments.

Departments of psychiatry in academic medical centers are being financially pressured by the many changes in the health care marketplace. The Medicare cutbacks of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, combined with rising facility expenses and changes in the fee structures of for-profit behavioral health care carve-out companies, have left academic psychiatry departments struggling with smaller revenues and higher expenses. In addition, the standards of care in academic departments often translate to somewhat higher costs of care, which limits the accessibility of the faculty and its psychiatric services to managed care patients. Limited access to managed care patients threatens not only revenues but also clinical teaching programs and research.

In response to these pressures, many departments of psychiatry have established their own behavioral health care programs. Several psychiatry departments have published descriptions of their programs: the University of Cincinnati (1), Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center (2), the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine (3), and the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center (4). Each of these departments found that it was fiscally feasible to operate their programs without abandoning their teaching and research missions. Hoge and Flaherty (5) conducted a comprehensive review of various models of the ways in which academic psychiatry departments have adapted to the changing environment of managed care. They suggested three approaches that departments might take, drawing on the unique values and characteristics of academic psychiatry departments.

Here we describe our experience in establishing and operating a fully capitated behavioral health care program from 1998 through 2000 for a population of 22,000 covered lives. We augment previous reports of academic departments of psychiatry by providing detailed financial data, including medical expenses, administrative costs, and utilization rates. We are aware that no amount of encouragement or positive reporting would induce an academic medical center to embark on a managed care program for which it takes capitated risk if it did not have comparative financial data on which to base its own actuarial studies. Our goal is to provide our colleagues in similar academic medical centers with the information needed to develop programs that will effectively compete with for-profit behavioral health programs.

The Johns Hopkins Medical Services Corporation

Background

In 1993 the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine embarked on a small fully capitated contract to provide mental health and substance abuse services to a portion (7,500 enrollees) of members of the Uniformed Services Family Health Plan (USFHP). The USFHP contract was a fully capitated medical and behavioral contract held by the Johns Hopkins Medical Services Corporation (MSC), an entity with a long history as a provider for the U.S. Department of Defense.

To provide the capitated services, the department of psychiatry used the administrative structure and clinical staff of one unit within the department that had successfully provided outpatient general mental health care as well as sexual health services—the sexual behaviors consultation unit—to patients for two decades. The department sought to gain operational experience in a managed behavioral care program with a small enrollment. Experience was gained, and loss was avoided, although in hindsight we recognize that a small enrollment is certainly no way to protect against catastrophic loss in an environment in which 5 percent of managed care patients can consume 50 percent of clinical funding (6).

Given the favorable experience with this pilot program and the recognized need for the department to evolve in the managed behavioral health care environment, the department of psychiatry proposed that it assume the responsibility for the behavioral health care services of the USFHP/TRICARE program at Johns Hopkins. The proposal emphasized the need for the academic department to gain experience in managed behavioral health care, the opportunity to upgrade the quality of clinical services, the ability to direct patients into Johns Hopkins services, and the opportunity to reintegrate mental health care and primary care. It included an agreement to manage the program at no additional cost to MSC.

In the spring of 1998, the carve-out contract with the for-profit behavioral health care company was terminated, and a capitated contract to provide mental health and substance abuse services for the 22,000 USFHP/TRICARE prime enrollees was awarded to the Johns Hopkins department of psychiatry. The contract was awarded for a period of two years—May 1998 through April 2000—to one of the two faculty practice plans of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

At the time of the transition of the contract from the for-profit managed care company to the department's program, slightly more than 300 enrollees were receiving treatment. The challenge was to maintain the integrity of the existing treatment plans while developing the department's provider network throughout Maryland. To achieve this goal, the current providers were asked to submit outpatient treatment reports that provided diagnostic and treatment information. If the existing providers were willing to accept the TRICARE fee schedule and submitted an appropriate treatment plan, continued services were authorized for the enrollee. All conditions were met in nearly all instances, and the transition went smoothly, with few complaints from either enrollees or providers.

Contract specifications

Projected utilization rates and expenses were based on the previous two years' experience with 7,500 USFHP enrollees, a convenience sample of the TRICARE population in the area. A funding rate of $5.70 per member per month for the 22,000 enrollees was agreed on, of which 44 cents was designated as a monthly administrative fee paid to the department for utilization review and care management. MSC retained responsibility for various administrative functions, including claims processing, member and provider services, and appeals processes. Thus $5.26 was earmarked for clinical services, or medical expenses.

This $5.26 capitation fee covered all mental health and substance abuse services—inpatient, residential, and outpatient services—as well as professional fees for faculty and network providers, who were to be paid on a fee-for-service basis. The geographic distribution of the patients, as well as the contract itself, allowed enrollees to choose a network provider with Johns Hopkins or a network provider in independent practice. Although the clinical funding was adequate, the administrative fee clearly was not, as discussed below.

The working relationships with network providers in independent practice were aided by selected site visits conducted by the clinical director (the first author) and the associate director of the office of clinical services. The purpose of these visits was to establish collaborative relationships and to get a better sense of the working conditions of the providers in the larger group practices. This has lent a "first-name-basis" tone to the conduct of patient authorization and management issues.

Risk sharing

An important element of the contract was the establishment of a 10 percent risk corridor around the total targeted funding for the program. The psychiatry department and MSC would split the risk for any deficit or excess within the 10 percent corridor. Deficits or excesses above the risk corridor would be the responsibility of MSC. The downside exposure to the department was $70,000, as was the opportunity for an incentive should the expenses not meet the projected funding level.

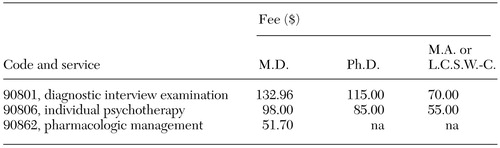

Fee structure

The covered benefits and the provider fee schedule were established according to the contract with the Department of Defense and were in accordance with the TRICARE prime benefits. We maximized the fees in accordance with the maximum allowable charges under the CHAMPUS fee schedule. Table 1 provides a sample of the contract's outpatient fees.

In Maryland, all inpatient facilities that include psychiatric units are exempt from the diagnosis-related-group system under a waiver from Medicare. Facility rates are set by the state's Health Services Cost Review Commission. The costs for inpatient hospitalization range from $615 to $633 per day for bed and nursing expenses; drugs and professional fees are billed separately. Under this federal waiver, hospitals cannot discount inpatient costs. Thus rates were not negotiated with individual facilities, and the rates could not be discounted. Accordingly, any use of the inpatient financial data in this article for the purposes of establishing industry benchmarks should take into consideration the unique inpatient rate-setting environment in Maryland.

Enrollees

Family members of active duty military personnel as well as retired military personnel and their families are eligible for enrollment in USFHP/TRICARE. The age distribution of the enrolled population receiving mental health and substance abuse services (N=1,234) was bimodal, because males between the ages of 20 and 45 years who are on active duty are not eligible to enroll, which greatly reduced the size of this subgroup. One-third of the patients were under 18 years of age. The mean±SD age was 36±21.7 years. Sixty percent of the enrollees who received treatment were females.

USFHP/TRICARE enrollees live throughout central Maryland but use Johns Hopkins hospitals in the city of Baltimore as a hub. The primary care sites are located as far as 75 miles west, 27 miles north, and 30 miles south of Baltimore. The contract stipulates that specialty delivery sites must involve no more than one hour's travel for enrollees. Thus local providers and facilities had to be developed to comply with the accessibility regulations of the contract.

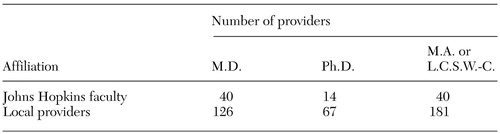

Provider network

We followed three guiding principles in establishing the provider network. First, given an appropriate treatment plan, the members currently receiving treatment would be allowed to continue with their current providers without interruption to their care. This decision had a lasting effect on the composition of the provider network, because most of the existing providers joined the new network. The result was a panel of providers who were geographically distributed to meet patients' needs and who were experienced in managed behavioral health care. The composition of the provider network is summarized in Table 2.

The second guiding principle was to give preference to Johns Hopkins faculty and facilities when making referrals. In practice, this meant developing intake and referral procedures that directed most of the patients in the Baltimore area to Johns Hopkins facilities and providers. A central telephone number for mental health and substance abuse treatment referrals was included on each enrollee's health plan membership card.

Third, multidisciplinary groups were favored over solo practices for inclusion on the provider panel, because group practices provide a greater range of services and more reliable access. During the first two years of the project, about 80 percent of authorized outpatient services provided by providers in independent practice were delivered by psychiatrists, psychologists, and master's-level mental health clinicians who were members of group practices. The use of group practices grew over the two years as referral operations developed.

Administrative staffing

The core personnel are administrative staff (1.75 full-time equivalents), an assistant director of clinical services (one full-time-equivalent master's-level social worker), and the director of clinical services (.8 full-time-equivalent doctoral-level clinical psychologist). The administrative staff is responsible for patient and provider inquiries, membership validation, entry of treatment authorization into the database, and mailing of authorization to providers. The assistant director provides preauthorization of services as required, conducts utilization reviews, and engages in extensive provider contact. The director of clinical services conducts occasional utilization reviews and is responsible for the program's database system as well as the administrative oversight of and reporting on the program.

In addition to the core staff, a faculty child psychiatrist conducts inpatient child and adolescent reviews (34 admissions over the two-year period), and a faculty specialist in substance abuse conducts substance abuse reviews for inpatients and persons in residential treatment for non-Hopkins facilities (25 admissions over the two-year period). A senior faculty member (the second author) is the medical director of the program. He is available for medical or psychiatric consultation on a case-by-case basis and provides medical administrative oversight for the program.

A faculty psychiatrist is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The on-call psychiatrist is responsible for authorizing admissions outside regular work hours and must be available to the primary care physicians and nurses on the after-hours telephone triage services for emergency consultations. The faculty members receive no direct compensation, on the assumption that the program will help improve the department's payer mix and, ultimately, its net fee-for-service revenue.

Integration of mental health and primary care

The integration of mental health services with primary care was a major goal of the new program, given that the previous program involved minimal clinical contact between mental health providers and primary care providers. We believe that early case finding and early intervention coordinated with the primary care physician results in better patient care and, ultimately, lower costs.

USFHP/TRICARE is served by 19 primary care offices staffed by 115 primary care managers: physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. The contract gives members the right to obtain initial mental health outpatient services (eight sessions) directly from providers without a referral from their primary care managers. In practice, this means that the primary care manager, rather than serving as a gatekeeper, is a case finder who collaborates with the mental health providers in the care of the enrollees.

Primary care physicians typically manage mental health problems and frequently prescribe psychotropic medications. For example, 14 percent of the children and 32 percent of the adults in our program who are treated by mental health providers receive medication prescriptions from their primary care physician.

Primary care physicians are regularly given information about their patients who are receiving mental health services. This information includes a summary of the initial treatment report and a list of recommended psychotropic medications, notification of mental health and substance abuse services received in the emergency department, notification of hospital admissions, and consultation when there is a significant change in status or management issues.

In addition, the department of psychiatry provides in-service training to the primary care physicians on topics such as depression among children, primary care management of depression, anxiety and substance abuse, medical care for persons with chronic mental illness, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder. In the first two contract years, 56 of 80 physicians (70 percent) attended one of four training sessions held. The mean scores of evaluations of the sessions on a 5-point Likert scale were 4.4 for the adult-oriented sessions and 4.6 for the pediatrics-oriented sessions (personal communication, McGuire M, 2001).

Utilization review

We have tried to make the utilization review process and the process for authorizing services as user-friendly as possible for both enrollees and network providers. We pay particular attention to the completion of the initial evaluations and treatment plans. When evaluations or treatment plans are incomplete, the providers are contacted by telephone and the case reviewed. In most instances the providers appreciate having the opportunity to review the case with another mental health professional.

No inpatient admission requested by a facility or a provider has ever been denied under the program. Although admission criteria must be met, we have elected to intensively manage the care of patients who are admitted rather than deny admission. Thus the process of inpatient reviews—particularly those within the Johns Hopkins family, in which providers and reviewers know each other professionally—is used to help the inpatient team take the important steps for initial discharge planning, including contacting the primary care provider and the current outpatient mental health provider.

Utilization reviews are low-key but persistent, occurring every three days on average during the course of the hospital admission. Our small program has essentially allowed for a collegial, but nevertheless intensive, case management program for inpatient admissions. In the one instance in which an additional day was not authorized, the additional day had been requested not for more treatment but because of delays in discharge arrangements. Other programs, including one large managed care organization, have also reported low rates (.8 percent) of denial of additional hospital days (7). Internal reporting is also low-key but persistent. Weekly reports of the level of inpatient and intensive care activity are distributed to key departmental and MSC administrative personnel.

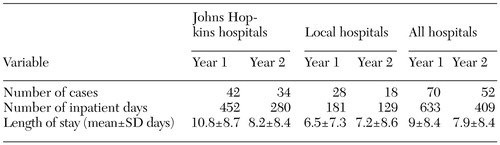

Inpatient utilization data

Inpatient utilization statistics for contract years 1 and 2 are compared in Table 3. In year 1 the total number of inpatient days per 1,000 lives was 30, which is comparable to national figures for "moderately managed" plans (8). The year 2 figure of 19.6 inpatient days per 1,000 lives is comparable to national figures for "aggressively managed" plans (8). The reason for the marked reduction in the number of inpatient days is not clear. The number of admissions declined in both university and community hospitals. Length of stay decreased by 24 percent in the university hospitals (the base rate was higher) but only by 11 percent in the local hospitals. Given the relatively low numbers in both groups, we currently regard these changes as trends to be watched. We would like to believe that open access to outpatient services and case management had a positive effect in terms of the reduction in admissions, but time may reveal that the use of inpatient services varies considerably from year to year.

The primary diagnostic groups of psychiatric inpatient admissions were affective disorders, 57 percent; schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, 14.6 percent; eating disorders, 5.7 percent, and adjustment disorders, 5.7 percent. Admissions for all other diagnostic groups were less than 5 percent.

A major concern associated with short stays is readmission due to incomplete treatment during the previous admission. Our readmission rates are comparable to published industry norms. The 90-day readmission rate decreased from 24 percent (11 patients) in the first year to 12 percent (three patients) in the second year. In describing readmission rates among 3,113 patients who were hospitalized in 1998, Nelson and associates (9) reported a 90-day readmission rate of 11 percent (201 patients) among those who kept at least one outpatient follow-up appointment after discharge and a rate of 15 percent (678 patients) among those who did not. Pooling these discharge rates yields an overall readmission rate of 14 percent.

Outpatient authorization data

In contract year 2, the penetration rate—the percentage of individual members who sought treatment—increased from 4.7 percent to 5.7 percent, and the number of authorized outpatient treatments increased from 31 to 39 per 1,000. The number of inpatient days per 1,000 decreased by 35 percent, whereas the number of members per 1,000 who gained access to services increased by 25 percent. During the second year—when presumably members are better informed about accessing resources—the penetration rate was comparable to rates in the pre-managed care era Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (5.8 percent) and the early 1990s National Comorbidity Survey (5.9 percent) (10).

Financial data

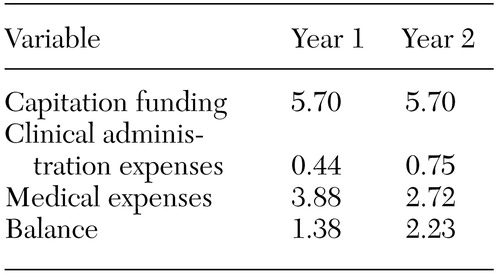

Weissman and associates (10) determined that providing adequate behavioral health services under capitation costs about $6 per member per month. The revenues and expenses for the program are summarized in Table 4. Actual medical expenses for the two years ranged from $2.72 to $3.88 per member per month. These figures are slightly higher than the costs of $2.75 to $3.50 per member per month for both medical expenses and administrative overhead recently reported by Reifler and associates (4). As the table shows, administrative costs increased from year 1 to year 2. The additional 31 cents per member per month covered the expense of administrative services developed during the first year, namely, network development, provider relations, data entry of authorization, and data analyses. The balance per member per month, which is the excess of revenues over expenses, was returned to MSC minus a $70,000 risk share payment. With a population of this size, two or three large claims can have a major effect on medical expenses (6). Thus the risk share payment has been committed to a cash reserve to protect the department against a future negative risk share and to fund pilot studies involving the program.

As a nonprofit organization, we need not be concerned with allocation of profits to shareholders. This, of course, is a fundamental characteristic of managed care organizations that should not go unnoticed.

Discussion

Departmental involvement in managed care

This report and those of others (1,2,3,45,11) suggest that, with appropriate funding, departments of psychiatry in academic medical centers can provide and manage mental health and substance abuse services in a capitated model in a manner that offers accessible, high-quality care to their patients. The lessons learned have led the department of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins to take on responsibility for 100,000 lives under a variety of managed care funding mechanisms. If all 126 medical schools in the country were to develop similar modest programs, 1.26 million lives would be covered by academic departments. Thus some portion of the population currently lost to many medical schools would be taken back from the for-profit carve-out managed care organizations.

Integrated mental health and primary care

It is important to involve primary care physicians in the behavioral health care system. Primary care providers are currently very much involved in the management of mental health problems. Sixty to 70 percent of all medical visits involve no medical or biological diagnosis that can be confirmed (12). An estimated 25 percent of patients who seek primary care treatment have one or more diagnosable mental disorders (13). More than 50 percent of patients with mental health problems are seen only in the general medical sector (14). Finally, about two-thirds of all prescriptions for psychotropic medications are written by physicians who are not psychiatrists (15). Our experience supports the now-recognized role of primary care physicians in managed behavioral health care.

Early treatment and case management is crucial. Delivering services to patients at the first indication of need, finding the patients who need services, and carefully managing those who are seriously ill are vitally important tasks in the successful management of a behavioral health care program. A patient's dropping out of care should never be viewed as a positive development, clinically or financially. Although funds may be saved in the short term, the patient will usually return and often will require more comprehensive services.

Conversely, by providing outpatient services to more members and authorizing more treatment programs, such as medical management together with psychotherapy, good care is provided in a timely manner to those who need it. This effort may have been one factor in the lower number of inpatient hospitalizations in the second year of the project. However, as we have noted, the small number of enrollees in the plan and the fact that only two years were studied make this possibility a hypothesis for further testing, not a conclusion.

Research and teaching components

Academic departments of psychiatry have been able to integrate behavioral health care with their research and teaching missions (11). Ideally, departments should involve residents in direct clinical care as well as in the administration of managed care programs. In addition, the opportunities for clinical research are extensive. Clinical research needs to examine treatment effectiveness and evidence-based practices of mental health and substance abuse services in natural settings, as opposed to treatment efficacy studies in controlled environments (16). Programs that are integrated with primary care have access to data that should permit researchers to critically examine social and behavioral aspects of the preventable causes of morbidity and mortality (17). Fortunately, the same database necessary for monitoring the authorization, utilization, and management of treatment can also be used to obtain needed information about treatment efficacy patterns (18).

Conclusions

Our experience has been positive both clinically and fiscally. The department has renewed its USFHP/TRICARE contract with MSC for an additional three years. We are in the process of expanding the programs and look forward to integrating the managed care operations with the teaching and research mission of the department.

Dr. Fagan and Dr. Schmidt are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Cook is vice-president of medical affairs for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians in Baltimore. Send correspondence to Dr. Fagan at Johns Hopkins at Green Spring Station, Office of Clinical Services, Falls Concourse, Suite 300, 10751 Falls Road, Lutherville, Maryland 21093 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Sample of services commonly authorized under a capitated behavioral health program and corresponding provider fees

|

Table 2. Composition of the Uniformed Services Family Health Plan/TRICARE provider network

|

Table 3. Use of inpatient services in year 1 (1998-1999) and year 2 (1999-2000) by enrollees in the managed behavioral health care plan

|

Table 4. Funding revenues and expenses for year 1 (1998-1999) and year 2 (1999-2000) of the managed behavioral health care plan, in dollars per member per month

1. Daniels AS: University-based single-specialty group: university managed care, in The Complete Capitation Handbook. Edited by Zieman GL. Tiburon, Calif, CentraLink, 1995Google Scholar

2. Wetzler S, Sanderson W, Schwartz BJ, et al: Academic psychiatry and managed care: a case study. Psychiatric Services 48:1019-1026, 1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Neufeld JD, Hales R, Callahan EJ, et al: Managed care: the behavioral health center: a model for academic managed care. Psychiatric Services 51:861-863, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Reifler B, Briggs J, Rosenquist P, et al: A managed behavioral health organization operated by an academic psychiatry department. Psychiatric Services 51:1273-1277, 2000Link, Google Scholar

5. Hoge MA, Flaherty JA: Reengineering clinical psychiatry in academic medical centers: processes and models of change. Psychiatric Services 52:63-67, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Lave JR, Peele PB: The distribution of payments for behavioral health care. Psychiatric Services 51:723, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Koike A, Klap R, Unutzer J: Utilization management in a large managed behavioral health organization. Psychiatric Services 51:621-626, 2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Melek SP, Pyenson BS: Actuarially determined capitation rates for mental health benefits: report prepared for the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2001Google Scholar

9. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL: Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatric Services 51:885-889, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Weisman E, Pettigrew K, Sotsky S, et al: The cost of access to mental health services in managed care. Psychiatric Services 51:664-665, 2000Link, Google Scholar

11. Hoge MA, Jacobs SC, Belitsky R: Psychiatric residency training, managed care, and contemporary clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 1001-1005, 2000Google Scholar

12. Cummings N: Does managed mental health care offset costs related to medical treatment? in Controversies in Managed Mental Health Care. Edited by Lazarus A. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

13. Brady D: What is the role of the primary care physician in managed mental health care? in ibidGoogle Scholar

14. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Melek SA: Financial, risk, and structural issues related to the integration of behavioral healthcare in primary care settings under managed care. Seattle, Milliman & Robertson, 1999Google Scholar

16. Bickman L: Practice makes perfect and other myths about mental health services. American Psychologist 54:965-978, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Schroder SA: Understanding health behavior and speaking out on the uninsured: two leadership opportunities. Academic Medicine 74:1163-1171, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Kiesler CA: The next wave of change for psychology and mental health services in the health care revolution. American Psychologist 55:481-487, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar