The Influence of Patients' Compensation-Seeking Status on the Perceptions of Veterans Affairs Clinicians

Abstract

The study compared clinicians' perceptions of three groups of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): those seeking compensation for PTSD, those not seeking compensation, and those certified as permanently disabled and thus not needing to reapply for benefits. The study subjects were 50 clinicians working in specialized PTSD programs of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The clinicians had a more negative view of the treatment engagement of veterans who were seeking compensation and of clinical work with these patients than they did in the case of the other two groups. The longer clinicians had been working with veterans who had PTSD, the more extreme were these negative perceptions. Most clinicians expressed a belief that the pursuit of service connection for PTSD has a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship and on clinical work in general.

Veterans who have disabilities can seek compensation through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for disorders incurred during or directly related to their military service. Once a veteran is deemed disabled and compensation is awarded, the veteran is said to be service connected for the disabling condition. Disability status is a significant contextual variable in treating any veteran in the VA system (1). Disability status is particularly salient in treating veterans who have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), because the vast majority of such patients who are treated in VA specialized PTSD programs apply for disability benefits (2).

Research on the impact of compensation-seeking status among patients with PTSD has been inconclusive. Some findings suggest that seeking compensation has a negative impact on the validity of evaluation for PTSD (3,4,5), the duration of hospitalization (6), and the magnitude of improvement among patients in long-term VA inpatient programs (2). However, another study showed that veterans who exaggerated their symptoms were no more likely to seek compensation than those who did not exaggerate (7).

In this study we compared clinicians' views of patients who were seeking compensation for PTSD with their views of patients who were not actively seeking compensation. Clinicians' perceptions are important because they may affect the course and the outcome of treatment (8).

Methods

Potential study subjects were clinicians in VA specialized PTSD programs. A random sample of program coordinators who were listed in the 1996 VA Directory of Specialized PTSD Programs were asked to distribute anonymous surveys to clinicians who were working on their teams. All the coordinators agreed and requested between three and 25 surveys. The number of surveys requested was only an approximation of the actual number of clinicians to whom coordinators would give the surveys.

A within-subject design was used in this study. Participants responded to the same set of questions in reference to three groups of patients with PTSD who differed in their compensation-seeking status. These three groups were the non-compensation-seeking group, defined as veterans who were not seeking service-connection benefits for the first time or were not seeking an elevation of their service-connection status and were not rated as permanently disabled as a result of PTSD; the compensation-seeking group, defined as veterans who were seeking service-connection benefits for the first time, were applying for an elevation of their service-connection status, were appealing a rejected claim, or were applying for permanent status; and the permanent compensation group, defined as veterans who were certified as permanently disabled because of PTSD and thus were awarded compensation without being subject to reevaluation.

The survey, developed for this study and based on concerns about the evaluation and treatment of veterans who seek compensation (9,10), included a 27-item questionnaire about treatment engagement. The questionnaire incorporates the Patient Engagement Subscale (PES) and the Therapist Engagement Subscale (TES). The 18-item PES asks about patients' involvement in treatment (Cronbach's alpha greater than .8 in all three patient groups). For example, the clinicians were asked to rate patients' motivation to improve and their trust in clinicians' commitment to helping them. The nine-item TES asks about the clinicians' work (Cronbach's alpha greater than .7 in all three patient groups). For example, clinicians rated their optimism about the patients' improvement and their work satisfaction while treating these patients.

Each item of the PES and the TES is rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 7, with 0, 3, 5, and 7 indicating that an attribute is not at all, a little, somewhat, or very present, respectively. Two additional questions asked respondents about the effect of pursuit of service connection for PTSD on the therapeutic relationship and treatment in general. The items used scales ranging from -5, very negatively, to 5, very positively.

Results

A total of 194 surveys were sent to 27 sites in 19 states in the East, the West, the Midwest, and the South as well as Washington, D.C. Sixty surveys were returned from 20 VA facilities in 16 states and in Washington, D.C., for a response rate of 31 percent. This rate is only a conservative estimate of the actual response rate, given the likelihood that not all the surveys were distributed.

Only surveys that included ratings for veterans in each of the three service-connection categories were retained for the analyses. Ten surveys were excluded because the respondents had never worked with veterans who were permanently service connected or with veterans who were not seeking compensation. The 50 remaining respondents comprised 12 psychiatrists, 13 psychologists, five social workers, eight nurses, two students, and ten respondents from other professions.

A majority of the respondents were male (30 respondents, or 60 percent), white (42 respondents, or 84 percent), nonveterans (33 respondents, or 66 percent) who had worked with both male and female outpatients with PTSD (40 respondents, or 80 percent). Half had worked with inpatients who had PTSD (26 clinicians, or 52 percent). All had worked with veterans who had a history of combat trauma, and most had worked with veterans who had a history of sexual trauma (40 respondents, or 80 percent). The mean±SD number of years that the clinician had been working with PTSD patients at a VA facility was 6±4.78. The study participants did not differ in ethnicity, sex, military experience, or profession from the clinicians who were excluded.

To determine how clinicians viewed the treatment engagement of the three groups of patients, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on PES scores. Service-connection status was the within-subject factor. This analysis showed a significant effect of service-connection status on clinicians' perceptions (F=49.14, df=2, 48, p<.001). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons showed that clinicians had the most favorable view of veterans who were not seeking compensation and the least favorable view of those who were seeking compensation; their views of the group of veterans who had been certified as permanently disabled fell in the middle (p<.05 for all comparisons).

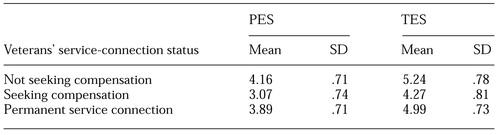

To determine how clinicians viewed their work with these three groups of patients, a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on TES scores, with service-connection status as the within-subject factor. This analysis showed a significant effect for service-connection status (F= 44.13, df=2, 48, p<.001). Clinicians had the most favorable view of their work with the veterans who were not seeking compensation and the least favorable view of their work with those who were seeking compensation; clinicians' perceptions of their work with the third group fell in the middle (p<.05 for all comparisons). The mean TES and PES scores are listed in Table 1.

A majority of clinicians indicated a belief that the pursuit of service connection had a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship (38 clinicians, or 78 percent) and a negative impact on treatment in general (38 clinicians, or 76 percent). Significant negative correlations were found between the number of years spent working with patients who had PTSD and clinicians' perceptions both of patients who were seeking compensation and of patients who were permanently disabled (r=-.31 and -.30, respectively, p<.05), indicating that the longer a clinician had been working with PTSD patients, the worse his or her perceptions of these two groups of veterans would be.

Discussion and conclusions

VA clinicians working in PTSD programs had a more negative view of the treatment engagement of patients who were seeking compensation for PTSD than of that of patients who were not actively seeking compensation. The fact that clinicians had more negative perceptions of veterans who were seeking compensation than of those who had been certified as permanently disabled suggests that compensation seeking per se and not the degree of functional limitation affects these perceptions. A veteran who is permanently service connected because of PTSD may be more disabled than one who is seeking compensation, because such a veteran has been identified as having chronic and intractable PTSD. The more time a clinician had spent working with patients who had PTSD, the more extreme these perceptions were. This finding suggests that the more experience clinicians accumulate, the more negative will be their view of the impact of compensation seeking on clinical work.

Caution is necessary in interpreting these results, because the response rate was low and the sample small. It is possible that only clinicians who had negative views of veterans who were seeking compensation completed surveys. Future research should examine the generalizability and validity of these findings and their impact on evaluation for and treatment of PTSD.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Veterans Affairs health services research and development grant II-R-98-057-2.

The authors are affiliated with the mental health patient service line of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 1 Veterans Drive, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55417 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sayer is also affiliated with the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis campus.

|

Table 1. Mean scores on the Patient Engagement Subscale (PES) and the Therapist Engagement Subscale(TES) of 50 clinicians who had worked with veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder

1. Mossman D: Veterans Affairs disability compensation: a case study in countertherapeutic jurisprudence. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 24:27-44, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

2. Fontana A, Rosenheck R: Effects of compensation-seeking on treatment outcomes among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:223-230, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frueh BC, Gold PB, Arellano MA: Symptom overreporting in combat veterans evaluated for PTSD: differentiation on the basis of compensation-seeking status. Journal of Personality Assessment 68:369-384, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Frueh BC, Smith DW, Barker SE: Compensation seeking status and psychometric assessment of combat veterans seeking treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9:427-439, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gold PB, Frueh BC: Compensation-seeking and extreme exaggeration of psychopathology among combat veterans evaluated for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:680-684,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pary R, Turns DM, Stephenson JJ, et al: Disability status and length of stay at a VA Medical Center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:844-845, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Smith DW, Frueh BC: Compensation seeking, comorbidity, and apparent exaggeration of PTSD symptoms among Vietnam combat veterans. Psychological Assessment 8:3-6, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Didato SV: Therapy failure: price and prejudice of the therapist? Mental Hygiene 55:219-220, 1972Google Scholar

9. Atkinson RM, Henderson RG, Sparr LF, et al: Assessment of Vietnam veterans for posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Administration disability claims. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1118-1121, 1982Link, Google Scholar

10. Spaulding WJ: Compensation for mental disability, in Psychiatry: Social, Epidemiologic, and Legal Psychiatry, 3rd ed. Edited by Michaels R. New York, Lippincott, 1988Google Scholar