When Taking Medications Is a Sin

To the Editor: In Massachusetts the Rogers decision gave patients the right to refuse medications in nonemergency situations unless they are deemed incompetent (1). Once patients are found incompetent to make treatment-related decisions, a "Rogers petition" is filed, seeking the court's substituted judgment in authorizing use of antipsychotic medications (2). As part of this process, psychiatrists first evaluate patients' competence to make treatment-related decisions (3). They then determine, among other things, whether patients have any religious reasons for not taking medications (1). At our institution, we found that in making these determinations, psychiatrists were considering only the active ingredients of medications, not their inert components.

Most religions do not restrict the use of antipsychotic medications. However, several of these medications contain inert substances that may be considered objectionable in some religions. In many cases, the capsules or coatings of medications are made from gelatin. Gelatin is derived from collagen, a protein found in animal skin and bones. Collagen, which is usually derived from cows and pigs, is extracted by pretreating the tissues with alkali or acid and then boiling them (4). Followers of three major religions—Hinduism, Judaism, and Islam—consider it a sin to consume products from one or both of these animals.

In a recent case, we were required to recommend an involuntary treatment plan for a patient whose religion prohibited consumption of pork products. To explore our options in this and similar cases, we sought the opinions of religious leaders of the three faiths. The leaders were unanimous in suggesting that available alternatives should be tried first. When alternative approaches fail or are not available, and if using the medications is the only way to preserve life or prevent further harm, then their use may be justified.

Psychiatrists have an obligation to respect their patients' religious preferences whenever they recommend any medications. Obtaining informed consent should include an acknowledgment that the recommended medications may contain offending animal products. If patients do not have the capacity to provide informed consent, psychiatrists should discuss this issue with a family member or guardian. Alternative approaches that are consistent with patients' religious wishes should be considered. If this is not possible, a risk-benefit analysis of the need for these medications should be made.

In many cases, the offending medications can safely be avoided. Several medications are available in liquid or elixir preparations that serve as viable alternatives to gelatin capsules. If capsules must be prescribed, the option of removing medications from the capsules should be explored. Sustained-release pills contain gelatin, and in some cases the non-sustained-release form of the medication can be substituted without causing significant harm. The gelatin composition of generic and brand-name medications may also differ.

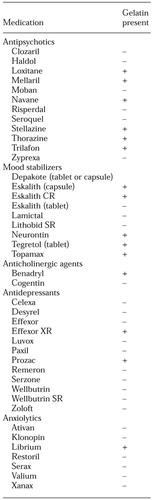

Information on the gelatin content of medications can be obtained from reference texts and from pharmaceutical manufacturers. Table 1 provides information from the Physicians' Desk Reference (5) on the gelatin content of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications.

If no alternatives are available, religious leaders of the patients' faith may be consulted. However, in substituted-judgment cases, the decision to use these medications may rest ultimately with the court.

Dr. Sattar is assistant professor of psychiatry and director of the Institute of Medicine and law at the University of Creighton School of Medicine in Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Pinals is assistant professor of psychiatry in the law and psychiatry program of the department of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

|

Table 1. Gelatin content of commonly prescribed psychotropic medication

1. Rogers v Commissioner of Mental Health, 2995. [Mass Supreme Judicial Court, 1983]Google Scholar

2. Gutheil TG, Appelbaum PS: The substituted judgment approach: its difficulties and limitations in mental health settings. Law, Medicine, and Health Care 13:61-64, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rogers v Okin, 478 F Supplementary 1342. [Mass Supreme Judicial Court, 1981]Google Scholar

4. Britannica Encyclopedia CD-ROM, 1999Google Scholar

5. Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics Company, 2001Google Scholar